New Study Maps Transience Of NZ Population

A newly published University of Canterbury study may help town planners and policymakers design better services for those who live in their communities.

The nationwide geospatial study – ‘Towards a better understanding of residential mobility and the environments in which adults reside’ – looks at the patterns of how people move, who moves around the most, and where they move.

Joint first author Dr

Lukas Marek from the University of Canterbury Geospatial

Research Institute’s GeoHealth Laboratory says it is known

that changes of address and related changes in environmental

exposures can be very important for people’s health and

wellbeing.

“Moving to a new place

can be a stressful event for many people, especially those

are forced to move to a new address, as opposed to those who

are buying or building a new house, or the people who want

to move. And there are a lot of people who move quite a lot

even though they don’t want to,” he

says.

The study would be of assistance to

policy makers and those looking at public health

issues.

“If you know your population is

fluctuating, this information will help decide on

appropriate investment in housing development and may also

shape how you design other

services.”

Socio-demographic and

socioeconomic factors were incorporated into the study of

data from 2016 - 2020, which maps spatial clusters of some

of the most and least mobile groups. Transience, or home

movement, was measured for every person in New Zealand

through access to a national research database with

individual and household-level

microdata.

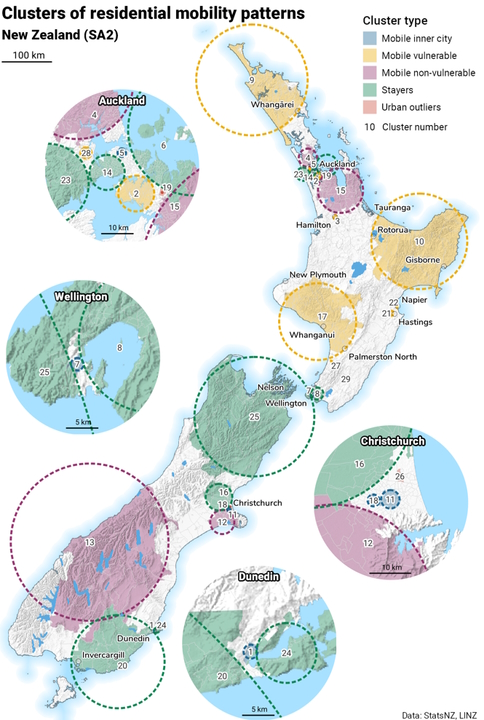

The study classified New Zealand

areas into five groups based on shared patterns around their

population’s movements.

Besides

long-term “stayers” (southeast, excluding central

Dunedin, and north of the South Island, outskirts of

Christchurch, Wellington and Auckland), the study

highlighted three distinct patterns for people moving

home:

- New housing developments (group called “mobile non-vulnerable”) located nearby Auckland, Christchurch and Southern Lakes;

- People who move for educational and work opportunities (“mobile inner city”) – city centres of major cities;

- and potential reliance on social and cheap

housing (“mobile

vulnerable”).

Vulnerable

transient populations were defined as people who moved at

least five times within the most deprived areas of New

Zealand (during the study’s timeframe), or 10 and more

times regardless of the area’s socioeconomic

status.

“For Māori, almost every 10th

person was what we described as a ‘vulnerable

transient’, compared to every 40th person for non-Māori,

meaning you are about four times more likely to be moving

homes at least once or twice a year or living only in the

most deprived areas if you are Māori,” Dr Marek

says.

A high percentage of people who are transient and vulnerable were based mostly in urban areas of Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), Whanganui, as well as around Te Tai Tokerau (Northland) and Tairāwhiti (East Cape).

Europeans and other ethnicities were highly represented in the stayers and mobile non-vulnerable people moving to new housing developments (noticeably south and west of Christchurch, in the Queenstown Lakes District and north of Auckland). Dr Marek believes it is interesting to see a shift in what community might mean in New Zealand: “A lot of our small towns often have really mobile populations. What does that mean for a community?”

“The paper does give an idea about which parts of the country has longer-term residents (stayers) and which has more transient populations,” he says.

“For councils it may mean that if you’re designing services for stayers but you actually have very transient populations, you need to think about what will work and how you interact with those who reside in your area. You may be able to create better conditions for people who actually live in your area now.”

- The study ‘Towards a better understanding of residential mobility and the environments in which adults reside: A nationwide geospatial study from Aotearoa New Zealand’ is available at: org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102762.

- National or international fast-food selling outlets

- Locally operated takeaways

- Dairy/convenience stores

- Fruit and vegetable outlets

- Supermarkets

- Physical activity facilities

- Alcohol outlets

- Gaming venues

- Green spaces (i.e. parks and forests)

- Blue spaces (rivers, lakes, sea etc)

Background

The

Healthy Location Index (HLI) published in 2021 provided

information for this 2023 study about “health-promoting”

and “health-constraining” environments. Researchers for

the HLI had compiled “environmental exposure” data into

10 measures:

For more information on the HLI,

visit https://tinyurl.com/goodsbads

International Writers' Workshop NZ Inc: Ōtepoti Poets Top The Kathleen Grattan Prize For A Sequence Of Poems

International Writers' Workshop NZ Inc: Ōtepoti Poets Top The Kathleen Grattan Prize For A Sequence Of Poems NZ Amateur Sport Association: 22 Amendments Proposed For 2022 Act Lodged On 22 November

NZ Amateur Sport Association: 22 Amendments Proposed For 2022 Act Lodged On 22 November Auckland University of Technology: Reading Helps Children Face A Difficult Future

Auckland University of Technology: Reading Helps Children Face A Difficult Future PATHA: Puberty Blocker Evidence Brief Affirms Aotearoa’s Approach

PATHA: Puberty Blocker Evidence Brief Affirms Aotearoa’s Approach Tataki Auckland Unlimited: Into Ocean & Ice - Unveiling Antarctica's Past And Present

Tataki Auckland Unlimited: Into Ocean & Ice - Unveiling Antarctica's Past And Present Health Coalition Aotearoa: Urgent Action Needed To Address Aotearoa’s Shameful Household Food Insecurity

Health Coalition Aotearoa: Urgent Action Needed To Address Aotearoa’s Shameful Household Food Insecurity