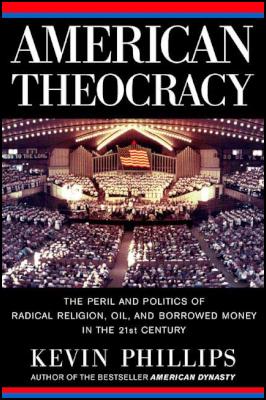

Kevin Phillips' New Book " American Theocracy"

American Theocracy: The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil, and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century

ISBN:

067003486X

Viking / Hardcover / 462 pages /

$26.95

Available March 21, 2006

PRE-ORDER FROM:

Amazon.com - Barnes & Noble.com or Booksense.com

IN THIS

REPORT:

American Theocracy

Introduction

Praise For American

Dynasty

American Theocracy

Description

American Theocracy

Contents

American Theocracy

Preface

Introduction:

Kevin Phillips, former Republican strategist and bestselling author of American Dynasty and Wealth and Democracy, provides a critical and extensively researched analysis of the current political condition as shaped by the “Republican Majority” and the alarming future it poses in his latest book, American Theocracy: The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil, and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century. This book will be published on March 21, 2006.

Phillips identifies the role of oil in American foreign policy, the intrusion of radical Christianity into politics, and the explosion of debt, and links them in a frightening vision of the future of America and the world.

The New York Times writes:

“What makes this book powerful in spite of the familiarity of many of its arguments is (Phillips’) rare gift for looking broadly and structurally at social and political change ... Phillips has created a harrowing picture of national danger that no American reader will welcome, but that none should ignore.”

Praise For American Dynasty:

"Devastating . . . an

important, troubling book that should be read everywhere

with care, nowhere more so than in this city."

—Jonathan

Yardley, The Washington Post Book

World

"(Phillips) is a deep thinker extraordinaire,

who does a masterful job of connecting the

military-industrial dots. . . . A searing indictment of the

Bush Dynasty."

—Douglas Brinkley, Mother

Jones

Description:

From America’s premier political analyst, an

explosive examination of the axis of religion, politics, and

borrowed money that threatens to destroy the nation

In his two most recent New York Times bestselling books, American Dynasty and Wealth and Democracy, Kevin Phillips established himself as a powerful critic of the political and economic forces that rule—and imperil—the United States, tracing the ever more alarming path of the emerging Republican majority’s rise to power. Now, Phillips takes an uncompromising view of the newest stage of the GOP majority: an inept and weakly led coalition, dominated by religious zealotry, that is losing America the world’s respect—and endangering her future.

From Ancient Rome to the British Empire, Phillips demonstrates that every world-dominating power has been brought down by an overlapping set of problems: a foolish combination of global overreach, militant religion, diminishing resources, and ballooning debt. It is exactly this nexus of ills that has come to define American’s political and economic identity at the start of this century. Matching his command of history with a penetrating analysis of contemporary politics, Phillips surveys a century of foreign policy and wars in the Middle East, showing how all, to one degree or another, reflected our ever-growing preoccupation with oil. Today, that dangerous inheritance includes clumsy military miscalculations, the ruinous occupation of Iraq, and sky-high oil prices.

He then turns to the surge of fundamentalist and evangelical religion in the United States, outlining the way a long tradition of radical and sectarian religion has taken an unprecedented political role under George W. Bush, as more and more Republicans think in apocalyptic terms and seek to shape domestic and foreign policy around religion. Finally, he documents how Wall Street and the business interests so closely allied with Washington have discarded the principles of sound finance that once characterized Republican fiscal policy and have literally mortgaged the country’s economic health to financial speculation, accompanied by an unprecedented level of public and private debt.

Oil, religion, and finance are not new elements in U.S. politics, but as Phillips makes clear with his formidable command of fact, figure, and history, and his long experience as a political strategist and observer, we are now in new and dangerous territory. The Bush coalition has resulted in a dearth of candor and serious strategy—a paralysis of policy and a government unable to govern. If left unchecked—the same forces will bring a preacher-ridden, debt-bloated, energy-crippled America to its knees. With an eye on the past and a searing vision of the future, Phillips confirms what too many Americans are still unwilling to admit about the depth of our misgovernment.

Kevin Phillips is a former Republican strategist, has been a political and economic commentator for more than three decades. He writes for the Los Angeles Times as well as Harper’s Magazine and Time. His thirteen books include the New York Times bestsellers American Dynasty, The Politics of Rich and Poor and Wealth and Democracy.

American Theocracy

CONTENTS

Preface vii

PART I: OIL AND AMERICAN SUPREMACY

1 Fuel and National Power 3

2 The

Politics of American Oil Dependence 31

3 Trumpets of

Democracy, Drums of Gasoline 68

PART II: TOO MANY PREACHERS

4 Radicalized Religion: As American As Apple Pie

99

5 Defeat and Resurrection: The Southernization of

America 132

6 The United States in a Dixie Cup: The New

Religious and Political Battlegrounds 171

7 Church,

State, and National Decline 218

PART III: BORROWED PROSPERITY

8 Soaring Debt, Uncertain Politics, and the

Financialization of the United States 265

9 Debt:

History’s Unlearned Lesson 298

10 Serial Bubbles and

Foreign Debt Holders: American Embarrassment and Asian

Opportunity 319

11 The Erring Republican Majority

347

Afterwards: The Changing Republican Presidential

Coalition 388

Acknowledgements 395

Notes

397

Index 431

PREFACE

The American people are not fools. That is why pollsters, inquiring during the last forty years whether the United States was on the right track or the wrong one, have so often gotten the second answer: wrong track. That was certainly the case again as the year 2005 closed out.

Because survey takers do not always pursue explanations, this book will venture some. Reckless dependency on shrinking oil supplies, a milieu of radicalized (and much too influential) religion, and a reliance on borrowed money—debt, in its ballooning size and multiple domestic and international deficits—now constitute the three major perils to the United States of the twenty-first century.

Shouldn’t war and terror be on the list? Yes—and they are, one step removed. Both derive much of their current impetus from the incendiary backdrop of oil politics and religious fundamentalism, in Islam as well as the West. Despite pretensions to motivations such as liberty and freedom, petroleum and its geopolitics have dominated Anglo-American activity in the Middle East for a full century. On this, history could not be more clear.

The excesses of fundamentalism, in turn, are American and Israeli, as well as the all-too-obvious depredations of radical Islam. The rapture, end-times, and Armageddon hucksters in the United States rank with any Shiite ayatollahs, and the last two presidential elections mark the transformation of the GOP into the first religious party in U.S. history.

The financialization of the United States economy over the last three decades—in the 1990s the finance, real-estate, and insurance sector overtook and then strongly passed manufacturing as a share of the U.S. gross domestic product—is an ill omen in its own right. However, its rise has been closely tied to record levels of debt and to the powerful emergence of a debt-and-credit industrial complex. Excessive debt in the twenty-first-century United States is on its way to becoming the global Fifth Horseman, riding close behind war, pestilence, famine, and fire.

This book’s title, American Theocracy, sums up a potent change in this country’s domestic and foreign policy making—religion’s new political prowess and its role in the projection of military power in the Middle Eastern Bible lands—that most people are just beginning to understand. We have had theocracies in North America before—in Puritan New England and later in Mormon Utah—but except in their earliest beginnings, they lacked the intensity of those in Europe, such as John Calvin’s Geneva or the Catholic Spain of the Inquisition.

Indeed, most of the Christian theocracies touched on by historians shared two unusual and virtually defining characteristics. First, they were very small in geographic terms. Second, and more important, they were the demographic results of migrations by true believers. The population of John Calvin’s sixteenth-century Geneva was swollen by French Protestant refugees, and the Dutch Reformed Calvinists of the Netherlands got a kindred infusion from Flemish refugees fleeing Spanish-controlled Antwerp. The Massachusetts Bay Colony, in turn, was built by English Puritan emigrants, and the nineteenth-century Mormons in Utah represented still another Zion-bound migration. As for Spain, despite militant Catholicism and the infamous Inquisition, it was too large and varied a nation to fit the small-scale theocratic pattern. Seventeenth-century attempts to shut down Spanish theaters, gambling houses, and brothels failed, and the golden age of Spanish literature and art—from Cervantes to El Greco—flourished in Toledo and Madrid under court, church, and noble patronage despite periodic homosexual reports and scandals that the Inquisition did not greatly pursue.1

Theocracy in America is of this lesser breed. The United States is too big and too diverse to resemble the Massachusetts Bay Colony of John Winthrop or sixteenth-century Geneva or even nineteenth-century Utah. A leading world power such as the United States, with almost three hundred million people and huge international responsibilities, goes about as far in a theocratic direction as it can when it satisfies the unfortunate criteria on display in Washington circa 2005: an elected leader who believes himself in some way to speak for God, a ruling political party that represents religious true believers and seeks to mobilize the churches, the conviction of many voters in that Republican party that government should be guided by religion, and on top of it all, White House implementation of domestic and international political agendas that seem to be driven by religious motivations and biblical worldviews. All of these factors and many more are discussed at length in part 2 of this book.

The three threats emphasized in these pages could stand on their own as menaces to the Republic. History, however, provides a further level of confirmation. Natural resources, religious excess, wars, and burgeoning debt levels have been prominent causes of the downfall of the previous leading world economic powers. The United States is hardly the first, and we can profit from the examples of what went wrong before.

Oil, as everyone knows, became the all-important fuel of American global ascendancy in the twentieth century. But before that, nineteenth-century Britain was the coal hegemon and seventeenth-century Dutch fortune harnessed the winds and the waters. Neither nation could maintain its global economic leadership when the world moved toward a new energy regime. Today’s United States, despite denials, has obviously organized much of its overseas military posture around petroleum, protecting oil fields, pipelines, and sea lanes.

But U.S. preoccupation with the Middle East has two dimensions. In addition to its concerns with oil and terrorism, the White House is courting end-times theologians and electorates for whom the holy lands are already a battleground of Christian destiny. Both pursuits, oil and biblical expectations, require a dissimulation in Washington that undercuts the U.S. tradition of commitment to the role of an informed electorate.

The political corollary—fascinating but appalling—is the recent transformation of the Republican presidential coalition. Since the elections of 2000 and especially of 2004, three pillars have become increasingly central: (1) the oil–national security complex, with its pervasive interests; (2) the religious right, with its doctrinal imperatives and massive electorate; and (3) the debt-dealing financial sector, which extends far beyond the old symbolism of Wall Street. In December 2004 The New York Times took up the term “borrower-industrial complex” to identify one profitable engine of exploding consumer debt.

That name does not quite work, but we can hardly use a term like the credit-card/mortgage/auto-loan/corporate-debt/federal-borrowing industrial complex. This is a problem still searching for its Election Day Halloween mask. In any event, the rapid ballooning of government, corporate, financial, and personal debt over the last four decades goes a long way to explain why the finance sector, debt’s toll collector, has swollen to outweigh the manufacture of real goods. We are in the midst of one of America’s most perverse transformations.

George W. Bush has promoted these alignments, interest groups, and their underpinning values. His family, over multiple generations, has been tied to a politics that conjoined finance, national security, and oil. In recent decades, operating from the federal executive branch, the Bushes have added close ties to evangelical and fundamentalist power brokers of many persuasions. These origins, biases, and practices were detailed in my last book, American Dynasty: Aristocracy, Fortune, and the Politics of Deceit in the House of Bush (2004). The present volume, therefore, revisits mostly the family’s influence in helping these trends and guiding these constituencies.

Over three decades of Bush presidencies, vice presidencies, and CIA directorships, the Republican party has slowly become the vehicle of all three interests—a fusion of petroleum-defined national security; a crusading, simplistic Christianity; and a reckless credit-feeding financial complex. The three are increasingly allied in commitment to Republican politics, if not in full agreement with one another. On the most important front, I am beginning to think that the southern-dominated, biblically driven Washington GOP represents a rogue coalition, like the southern, proslavery politics that controlled Washington until Lincoln’s election in 1860.

But the national Democrats have their own complicity. Their lack of understanding and moxie has contributed to the mutation of the GOP. Without that weak and muddled opposition, both before and after September 11, the Republican transformation would have been impolitic and perhaps impossible.

Clearly the pitfalls of petro-politics, radical religion, and debt finance have to be addressed in their own right. However, I have a personal concern over what has become of the Republican coalition. Forty years ago, I began a book, finished in 1967 and taken to the 1968 Republican presidential campaign, for which I became the chief political and voting-patterns analyst. Published in 1969, while I was still in the fledgling Nixon administration, The Emerging Republican Majority became highly controversial. Newsweek identified it as “The political bible of the Nixon Era.”

In that book I coined the term “Sun Belt” to describe the oil, military, aerospace, and retirement country that stretched from Florida to California, but debate concentrated on the argument—since fulfilled and then some—that the South was on its way into the national Republican party. Four decades later, this framework has produced the triple mutation that this book will discuss.

Some of that evolution was always implicit. If any region of the United States had the potential to produce a high-powered, crusading fundamentalism, it was Dixie. If any new alignment had the potential to nurture a fusion of oil interests and the military-industrial complex, it was the Sun Belt that helped to draw them into commercial and political proximity and collaboration. Wall Street, of course, has long been part of the GOP coalition. On the other hand, members of the Downtown Association and the Links Club were never enthusiastic about “Joe Sixpack” and middle America, to say nothing of preachers such as Oral Roberts or the Tupelo, Mississippi, Assemblies of God. The new cohabitation is an unnatural one.

Little was said about oil in The Emerging Republican Majority, partly because I knew I would be in the government when the book appeared. Still, oilmen liked its political thesis, and I fleshed out an analysis still relevant today—that the nation’s oil, coal, and natural-gas sections, despite their intramural differences, would be regional mainstays of the new “heartland”-centered GOP national coalition. Hitherto, these interests had been divided by the political Mason-Dixon Line. That division would and did end.

While studying economic geography and history in Britain some years earlier, I had been intrigued by the Eurasian “heartland” theory of Sir Halford Mackinder, a prominent early-twentieth-century geographer. Control of the heartland, Mackinder argued, would determine control of the world. In North America, I thought the coming together of a heartland—across fading Civil War lines—would determine control of Washington.

Wordsmith William Safire, in his The New Language of Politics entry on the heartland, cited Mackinder. He then noted that “political analyst Kevin Phillips applied the old geopolitical word to U.S. politics in his 1969 book The Emerging Republican Majority: ‘Twenty-one of the twenty-five Heartland states supported Richard Nixon in 1968. . . . Over the remainder of the century, the Heartland should dominate American politics in tandem with suburbia, the South and Sun Belt–swayed California.’”2

This was the prelude to today’s “red states.” Mackinder’s worldview has its own second wind because his Eurasian cockpit has reemerged as the pivot of the international struggle for oil. In a similar context, the American heartland, from Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico to Ohio and the Appalachian coal states, has become (along with the rest of the onetime Confederacy) the seat of a fossil-fuels political alliance—an electoral hydrocarbon coalition. It cherishes SUVs and easy carbon dioxide emissions policy, and applauds preemptive U.S. air strikes on uncooperative, terrorist-coddling Persian Gulf countries fortuitously blessed with huge reserves of oil.

Because the United States is beginning to run out of its own oil sources, a military solution to an energy crisis is hardly lunacy. Neither Caesar nor Napoléon would have flinched, and the temptation, at least, is understandable. What Caesar and Napoléon did not face, but less able American presidents do, is that bungled overseas military embroilment, unfortunate in its own right, could also boomerang economically. The United States, some $4 trillion in hock internationally, has become the world’s leading debtor, increasingly nagged by worry that some nations will sell dollars in their reserves and switch their holdings to rival currencies. Washington prints bonds and dollar-green IOUs, which European and Asian bankers accumulate until for some reason they lose patience. This is the debt Achilles’ heel, which stands alongside the oil Achilles’ heel.

Unfortunately, as much or more dynamite hides in the responsiveness of the new GOP coalition to Christian evangelicals, fundamentalists, and Pentecostals, who muster some 40 percent of the party electorate. Many, many millions believe that the Armageddon described in the Bible is coming soon. Chaos in the explosive Middle East, far from being a threat, actually heralds the awaited second coming of Jesus Christ. Oil-price spikes, murderous hurricanes, deadly tsunamis, and melting polar ice caps lend further credence.

The potential interaction between the end-times electorate, inept pursuit of Persian Gulf oil, Washington’s multiple deceptions, and the credit and financial crisis that could follow a substantial liquidation by foreign holders of U.S. bonds is the stuff of nightmares. To watch U.S. voting patterns enable such policies—the GOP coalition is unlikely to turn back—is depressing to someone who spent many years researching, watching, and cheering those grass roots.

Four decades ago, although The Emerging Republican Majority said little about southern fundamentalists and evangelicals, the new GOP coalition seemed certain to enjoy a major infusion of conservative northern Catholics and southern Protestants. This troubled me not at all. During the 1970s and part of the 1980s, I agreed with the predominating Republican argument that “secular” liberals, by badly misjudging the depth and importance of religion in the United States, had given conservatives a powerful and legitimate electoral opportunity.

Since then, my appreciation of the intensity of religion in the United States has deepened. Its huge carryover from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries turns out to have seeded a similar evangelical wave in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In 1998, after years of research, I published The Cousins’ Wars, a lengthy study of the three great English-speaking internal convulsions—the English Civil War of the 1640s, the American Revolution, and the American War Between the States. Amid each fratricide, religious divisions figured so strongly in people’s choosing sides that persisting threads became clear—pietists and puritans versus high-church adherents, and a recurrent conviction by militant evangelicals, from the 1640s to the 1860s, culminating in the American Civil War, that theirs was the cause of liberty and the Protestant Reformation. The overall analysis and its documentation were taken seriously enough that the book became a finalist for that year’s Pulitzer Prize in history. Indeed, my wife and I were sufficiently impressed by the historical roles of the scores of eighteenth-century churches we visited—from the pastel Caribbean stuccos of Anglican South Carolina to the stone fortresses of Presbyterian Pennsylvania and the white Congregational meetinghouses of New England—to think of writing a book on them sometime (we still do).

Such was religion’s enduring importance in the United States when it was trod upon in the 1960s and thereafter by secular advocates determined to push Christianity out of the public square, a mistake that unleashed an evangelical, fundamentalist, and Pentecostal counterreformation that in some ways is still building. As part 2 will explore, strong theocratic pressures are already visible in the Republican national coalition and its leadership, while the substantial portion of Christian America committed to theories of Armageddon and the inerrancy of the Bible has already made the GOP into America’s first religious party.

Its religiosity reaches across the board—from domestic policy to foreign affairs. Besides providing critical support for invading Iraq, widely anathematized by preachers as a second Babylon, the Republican coalition’s clash with science has seeded half a dozen controversies. These include Bible-based disbelief in Darwinian theories of evolution, dismissal of global warming, disagreement with geological explanations of fossil-fuel depletion, religious rejection of global population planning, derogation of women’s rights, opposition to stem-cell research, and so on. This suggests that U.S. society and politics may again be heading for a defining controversy such as the Scopes trial of 1925. That embarrassment chastened fundamentalism for a generation, but the outcome of the eventual twenty-first-century test is hardly assured.

Book buyers will understand that in these United States volumes able to sell two or three hundred thousand hardcover copies are uncommon. Not rare, just uncommon. Consider, then, the publishing success of end-times preacher Tim LaHaye, earlier the politically shrewd founder (in 1981) of the Washington-based Council for National Policy. Beginning in 1994 LaHaye successfully coauthored a series of books on the rapture, the tribulation, and the road to Armageddon that has since sold some sixty million copies in print, video, and cassette forms. Evangelist Jerry Falwell hailed it as probably the most influential religious publishing event since the Bible.3 Several novels of the Left Behind series rose to number one on the New York Times fiction bestseller list, and the series as a whole almost certainly reached fifteen to twenty million American voters. Political aides in the Bush White House must have read several volumes, if only for pointers on constituency sentiment.

In that respect, the books were highly informative. LaHaye’s novels furnished hints rarely discussed by serious publications as to why George W. Bush’s 2002–2003 call for war in Iraq included jeering at the United Nations, harped on the evil regime in Baghdad, and pretended that democracy, not oil, was the motive. LaHaye had authored essentially that plot almost a decade earlier. His evil antichrist, who had a French financial adviser and rose to power through the United Nations, was headquartered in New Babylon, Iraq, not far from the Baghdad of Bush’s arch-devil, Saddam Hussein. The fictional Tribulation Force, which fought in God’s name, represented goodness and had nothing to do with oil, which was one of the antichrist’s evil chessboards.

Twenty years ago, The New York Times would not have considered LaHaye for the bestseller list, and my scenario of his writings influencing the White House could only have been spoof. Not so today. In a late-2004 speech, the retiring television journalist Bill Moyers, himself an ordained Baptist minister, broke with polite convention. He told an audience at the Harvard medical school that “one of the biggest changes in politics in my lifetime is that the delusional is no longer marginal. It has come in from the fringe, to sit in the seat of power in the Oval Office and in Congress. For the first time in our history, ideology and theology hold a monopoly of power in Washington.”4

I would put it somewhat differently. These developments have warped the Republican party and its electoral coalition, muted Democratic voices, and become a gathering threat to America’s future. No leading world power in modern memory has become a captive, even a partial captive, of the sort of biblical inerrancy—backwater, not mainstream—that dismisses modern knowledge and science. The last parallel was in the early seventeenth century, when the papacy, with the agreement of inquisitional Spain, disciplined the astronomer Galileo for saying that the sun, not the earth, was the center of our solar system.

Conservative true believers will scoff: the United States is sui generis, they say, a unique and chosen nation. What did or did not happen to Rome, imperial Spain, the Dutch Republic, and Britain is irrelevant. The catch here, alas, is that these nations also thought they were unique and that God was on their side. The revelation that He was apparently not added a further debilitating note to the later stages of each national decline. Perhaps the warfare, earthquakes, plagues, and turmoil of the early twenty-first century are unprecedented, but the religious believers of yesteryear also saw millennial signs in flood, plagues, famines, comets, and Mongol and Turkish invasions.

Over the course of the last twenty-five years, I have made frequent reference to these political, economic, and historical (but not religious) precedents in several books, most recently in Wealth and Democracy (2002). The concentration of wealth that developed in the United States in the long bull market of 1982–2000 was also a characteristic of the zeniths of the previous leading world economic powers as their elites pursued surfeit in Mediterranean villas or in the country-house splendor of Edwardian England.

This volume, to be sure, is mostly about something other than wealth. Its concluding chapters in part 3 concentrate on the perils of debt, albeit that is also a financial excess. As we will see, wealth and debt have often overextended together in the modern trajectories of leading world economic powers. In a nation’s early years, debt is a vital and creative collaborator in economic expansion; in late stages, it becomes what Mr. Hyde was to Dr. Jekyll: an increasingly dominant mood and facial distortion. The United States of the early twenty-first century is well into this debt-driven climactic, with some critics arguing—all too plausibly—that an unsustainable credit bubble has replaced the stock bubble that burst in 2000.

Unfortunately, as my subtitle argues, three of the preeminent weaknesses displayed in these past declines have been religious excess, an outdated or declining energy and industrial base, and financialization and debt (from foreign and military overstretch). The examples have been clear, and they thread my analysis in this book. The extent to which politics in the United States—and especially the governing Republican coalition—deserves much of the blame for this fatal convergence is not only the book’s subject matter but its raison d’être.

World Economic Forum: Gender Gap Closes At Fastest Rate Since Pandemic

World Economic Forum: Gender Gap Closes At Fastest Rate Since Pandemic KidsRights: KidsRights Index 2025 Now Available

KidsRights: KidsRights Index 2025 Now Available CNS: We Can Do Better So That All People With HIV Live Healthy Normal Lifespans

CNS: We Can Do Better So That All People With HIV Live Healthy Normal Lifespans John Divinagracia, IMI: The Evolution Of Mankind’s First Voice - How Drums Shape The Human Story

John Divinagracia, IMI: The Evolution Of Mankind’s First Voice - How Drums Shape The Human Story Deep Sea Mining Campaign: New Report Exposes Impossible Metals’ Claims As Scientifically Baseless

Deep Sea Mining Campaign: New Report Exposes Impossible Metals’ Claims As Scientifically Baseless Pacific Whale Fund: First Māori Voice Opens UN Oceans Conference, Pushing For Marine Legal Rights

Pacific Whale Fund: First Māori Voice Opens UN Oceans Conference, Pushing For Marine Legal Rights