Iraq’s Weapons Of Mass Destruction – Full Report

IRAQ’S

WEAPONS OF

MASS

DESTRUCTION

THE ASSESSMENT OF THE

BRITISH

GOVERNMENT

From http://www.ukonline.gov.uk/featurenews/iraqdossier.pdf

CONTENTS

Foreword by the Prime Minister

3

Executive Summary 5

Part 1: Iraq’s Chemical, Biological,

Nuclear and Ballistic Missile Programmes 9

Chapter 1: The role of intelligence 9

Chapter 2: Iraq’s programmes 1971–1998

11

Chapter 3: The current position

1998–2002 17

Part 2: History of UN Weapons Inspections 33

Part 3: Iraq under Saddam Hussein 43

FOREWORD

BY THE PRIME MINISTER, THE RIGHT HONOURABLE TONY BLAIR

MP The document published today is based, in large

part, on the work of the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC).

The JIC is at the heart of the British intelligence

machinery. It is chaired by the Cabinet Office and made up

of the heads of the UK’s three Intelligence and Security

Agencies, the Chief of Defence Intelligence, and senior

officials from key government departments. For over 60 years

the JIC has provided regular assessments to successive Prime

Ministers and senior colleagues on a wide range of foreign

policy and international security issues.

Its work, like

the material it analyses, is largely secret. It is

unprecedented for the Government to publish this kind of

document. But in light of the debate about Iraq and Weapons

of Mass Destruction (WMD), I wanted to share with the

British public the reasons why I believe this issue to be a

current and serious threat to the UK national interest. In

recent months, I have been increasingly alarmed by the

evidence from inside Iraq that despite sanctions, despite

the damage done to his capability in the past, despite the

UN Security Council Resolutions expressly outlawing it, and

despite his denials, Saddam Hussein is continuing to develop

WMD, and with them the ability to inflict real damage upon

the region, and the stability of the world. Gathering

intelligence inside Iraq is not easy. Saddam’s is one of the

most secretive and dictatorial regimes in the world. So I

believe people will understand why the Agencies cannot be

specific about the sources, which have formed the judgements

in this document, and why we cannot publish everything we

know. We cannot, of course, publish the detailed raw

intelligence. I and other Ministers have been briefed in

detail on the intelligence and are satisfied as to its

authority. I also want to pay tribute to our Intelligence

and Security Services for the often extraordinary work that

they do. What I believe the assessed intelligence has

established beyond doubt is that Saddam has continued to

produce chemical and biological weapons, that he continues

in his efforts to develop nuclear weapons, and that he has

been able to extend the range of his ballistic missile

programme. I also believe that, as stated in the document,

Saddam will now do his utmost to try to conceal his weapons

from UN inspectors. The picture presented to me by the JIC

in recent months has become more not less worrying. It is

clear that, despite sanctions, the policy of containment has

not worked sufficiently well to prevent Saddam from

developing these weapons. I am in no doubt that the threat

is serious and current, that he has made progress on WMD,

and that he has to be stopped. Saddam has used chemical

weapons, not only against an enemy state, but against his

own people. Intelligence reports make clear that he sees the

building up of his WMD capability, and the belief overseas

that he would use these weapons, as vital to his Page

3 strategic interests, and in particular his goal of

regional domination. And the document discloses that his

military planning allows for some of the WMD to be ready

within 45 minutes of an order to use them. I am quite

clear that Saddam will go to extreme lengths, indeed has

already done so, to hide these weapons and avoid giving them

up. In today’s inter-dependent world, a major regional

conflict does not stay confined to the region in question.

Faced with someone who has shown himself capable of using

WMD, I believe the international community has to stand up

for itself and ensure its authority is upheld. The threat

posed to international peace and security, when WMD are in

the hands of a brutal and aggressive regime like Saddam’s,

is real. Unless we face up to the threat, not only do we

risk undermining the authority of the UN, whose resolutions

he defies, but more importantly and in the longer term, we

place at risk the lives and prosperity of our own

people. The case I make is that the UN Resolutions

demanding he stops his WMD programme are being flouted; that

since the inspectors left four years ago he has continued

with this programme; that the inspectors must be allowed

back in to do their job properly; and that if he refuses, or

if he makes it impossible for them to do their job, as he

has done in the past, the international community will have

to act. I believe that faced with the information

available to me, the UK Government has been right to support

the demands that this issue be confronted and dealt with. We

must ensure that he does not get to use the weapons he has,

or get hold of the weapons he wants. Page 4 EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY 1. Under Saddam Hussein Iraq developed chemical

and biological weapons, acquired missiles allowing it to

attack neighbouring countries with these weapons and

persistently tried to develop a nuclear bomb. Saddam has

used chemical weapons, both against Iran and against his own

people. Following the Gulf War, Iraq had to admit to all

this. And in the ceasefire of 1991 Saddam agreed

unconditionally to give up his weapons of mass

destruction. 2. Much information about Iraq’s weapons of

mass destruction is already in the public domain from UN

reports and from Iraqi defectors. This points clearly to

Iraq’s continuing possession, after 1991, of chemical and

biological agents and weapons produced before the Gulf War.

It shows that Iraq has refurbished sites formerly associated

with the production of chemical and biological agents. And

it indicates that Iraq remains able to manufacture these

agents, and to use bombs, shells, artillery rockets and

ballistic missiles to deliver them. 3. An independent and

well-researched overview of this public evidence was

provided by the International Institute for Strategic

Studies (IISS) on 9 September. The IISS report also

suggested that Iraq could assemble nuclear weapons within

months of obtaining fissile material from foreign

sources. 4. As well as the public evidence, however,

significant additional information is available to the

Government from secret intelligence sources, described in

more detail in this paper. This intelligence cannot tell us

about everything. However, it provides a fuller picture of

Iraqi plans and capabilities. It shows that Saddam Hussein

attaches great importance to possessing weapons of mass

destruction which he regards as the basis for Iraq’s

regional power. It shows that he does not regard them only

as weapons of last resort. He is ready to use them,

including against his own population, and is determined to

retain them, in breach of United Nations Security Council

Resolutions (UNSCR). 5. Intelligence also shows that Iraq

is preparing plans to conceal evidence of these weapons,

including incriminating documents, from renewed inspections.

And it confirms that despite sanctions and the policy of

containment, Saddam has continued to make progress with his

illicit weapons programmes. 6. As a result of the

intelligence we judge that Iraq has: - continued to

produce chemical and biological agents; - military plans

for the use of chemical and biological weapons, including

against its own Shia population. Some of these weapons are

deployable within 45 minutes of an order to use them; -

command and control arrangements in place to use chemical

and biological weapons. Authority ultimately resides with

Saddam Hussein. (There is intelligence that he may have

delegated this authority to his son Qusai); Page 5 -

developed mobile laboratories for military use,

corroborating earlier reports about the mobile production of

biological warfare agents; - pursued illegal programmes to

procure controlled materials of potential use in the

production of chemical and biological weapons

programmes; - tried covertly to acquire technology and

materials which could be used in the production of nuclear

weapons; - sought significant quantities of uranium from

Africa, despite having no active civil nuclear power

programme that could require it; - recalled specialists to

work on its nuclear programme; - illegally retained up to

20 al-Hussein missiles, with a range of 650km, capable of

carrying chemical or biological warheads; - started

deploying its al-Samoud liquid propellant missile, and has

used the absence of weapons inspectors to work on extending

its range to at least 200km, which is beyond the limit of

150km imposed by the United Nations; - started producing

the solid-propellant Ababil-100, and is making efforts to

extend its range to at least 200km, which is beyond the

limit of 150km imposed by the United Nations; -

constructed a new engine test stand for the development of

missiles capable of reaching the UK Sovereign Base Areas in

Cyprus and NATO members (Greece and Turkey), as well as all

Iraq’s Gulf neighbours and Israel; - pursued illegal

programmes to procure materials for use in its illegal

development of long range missiles; - learnt lessons from

previous UN weapons inspections and has already begun to

conceal sensitive equipment and documentation in advance of

the return of inspectors. 7. These judgements reflect the

views of the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC). More

details on the judgements and on the development of the

JIC’s assessments since 1998 are set out in Part 1 of this

paper. 8. Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction are in breach

of international law. Under a series of UN Security Council

Resolutions Iraq is obliged to destroy its holdings of these

weapons under the supervision of UN inspectors. Part 2 of

the paper sets out the key UN Security Council Resolutions.

It also summarises the history of the UN inspection regime

and Iraq’s history of deception, intimidation and

concealment in its dealings with the UN inspectors. Page

6 9. But the threat from Iraq does not depend solely on

the capabilities we have described. It arises also because

of the violent and aggressive nature of Saddam Hussein’s

regime. His record of internal repression and external

aggression gives rise to unique concerns about the threat he

poses. The paper briefly outlines in Part 3 Saddam’s rise to

power, the nature of his regime and his history of regional

aggression. Saddam’s human rights abuses are also

catalogued, including his record of torture, mass arrests

and summary executions. 10. The paper briefly sets out how

Iraq is able to finance its weapons programme. Drawing on

illicit earnings generated outside UN control, Iraq

generated illegal income of some $3 billion in 2001. Page

7 Page 8 CHAPTER 1: 1. Since UN inspectors were withdrawn

from Iraq in 1998, there has been little overt information

on Iraq’s chemical, biological, nuclear and ballistic

missile programmes. Much of the publicly available

information about Iraqi capabilities and intentions is

dated. But we also have available a range of secret

intelligence about these programmes and Saddam Hussein’s

intentions. This comes principally from the United Kingdom’s

intelligence and analysis agencies – the Secret Intelligence

Service (SIS), the Government Communications Headquarters

(GCHQ), the Security Service, and the Defence Intelligence

Staff (DIS). We also have access to intelligence from close

allies. 2. Intelligence rarely offers a complete account

of activities which are designed to remain concealed. The

nature of Saddam’s regime makes Iraq a difficult target for

the intelligence services. Intelligence, however, has

provided important insights into Iraqi programmes and Iraqi

military thinking. Taken together with what is already known

from other sources, this intelligence builds our

understanding of Iraq’s capabilities and adds significantly

to the analysis already in the public domain. But

intelligence sources need to be protected, and this limits

the detail that can be made available. 3. Iraq’s

capabilities have been regularly reviewed by the Joint

Intelligence Committee (JIC), which has provided advice to

the Prime Minister and his senior colleagues on the

developing assessment, drawing on all available sources.

Part 1 of this paper includes some of the most significant

views reached by the JIC between 1999 and 2002. Joint

Intelligence Committee (JIC) The JIC is a Cabinet

Committee with a history dating back to 1936. The JIC brings

together the Heads of the three Intelligence and Security

Agencies (Secret Intelligence Service, Government

Communications Headquarters and the Security Service), the

Chief of Defence Intelligence, senior policy makers from the

Foreign Office, the Ministry of Defence, the Home Office,

the Treasury and the Department of Trade and Industry and

representatives from other Government Departments and

Agencies as appropriate. The JIC provides regular

intelligence assessments to the Prime Minister, other

Ministers and senior officials on a wide range of foreign

policy and international security issues. It meets each week

in the Cabinet Office. Page 9 Page 10 CHAPTER 2 1. Iraq has been involved in chemical and

biological warfare research for over 30 years. Its chemical

warfare research started in 1971 at a small, well guarded

site at Rashad to the north east of Baghdad. Research was

conducted there on a number of chemical agents including

mustard gas, CS and tabun. Later, in 1974 a dedicated

organisation called al-Hasan Ibn al-Haitham was established.

In the late 1970s plans were made to build a large research

and commercial-scale production facility in the desert some

70km north west of Baghdad under the cover of Project 922.

This was to become Muthanna State Establishment, also known

as al-Muthanna, and operated under the front name of Iraq’s

State Establishment for Pesticide Production. It became

operational in 1982-83. It had five research and development

sections, each tasked to pursue different programmes. In

addition, the al-Muthanna site was the main chemical agent

production facility, and it also took the lead in

weaponising chemical and biological agents including all

aspects of weapon development and testing, in association

with the military. According to information, subsequently

supplied by the Iraqis, the total production capacity in

1991 was 4,000 tonnes of agent per annum, but we assess it

could have been higher. Al-Muthanna was supported by three

separate storage and precursor production facilities known

as Fallujah 1, 2 and 3 near Habbaniyah, north west of

Baghdad, parts of which were not completed before they were

heavily bombed in the 1991 Gulf War. 2. Iraq started

biological warfare research in the mid-1970s. After

small-scale research, a purpose-built research and

development facility was authorised at al-Salman, also known

as Salman Pak. This is surrounded on three sides by the

Tigris river and situated some 35km south of Baghdad.

Although some progress was made in biological weapons

research at this early stage, Iraq decided to concentrate on

developing chemical agents and their delivery systems at

al-Muthanna. With the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, in the

early 1980s, the biological weapons programme was revived.

The appointment of Dr Rihab Taha in 1985, to head a small

biological weapons research team at al-Muthanna,

Effects of Chemical Weapons Mustard is a

liquid agent, which gives off a hazardous vapour, causing

burns and blisters to exposed skin. When inhaled, mustard

damages the respiratory tract; when ingested, it causes

vomiting and diarrhoea. It attacks and damages the eyes,

mucous membranes, lungs, skin, and blood-forming

organs. Tabun, sarin and VX are all nerve agents

of which VX is the most toxic. They all damage the nervous

system, producing muscular spasms and paralysis. As little

as 10 milligrammes of VX on the skin can cause rapid

death. Page 11 helped to develop the programme. At about

the same time plans were made to develop the Salman Pak site

into a secure biological warfare research facility. Dr Taha

continued to work with her team at al-Muthanna until 1987

when it moved to Salman Pak, which was under the control of

the Directorate of General Intelligence. Significant

resources were provided for the programme, including the

construction of a dedicated production facility (Project

324) at al-Hakam. Agent production began in 1988 and

weaponisation testing and later filling of munitions was

conducted in association with the staff at Muthanna State

Establishment. From mid-1990, other civilian facilities were

taken over and some adapted for use in the production and

research and development of biological agents. These

included: - al-Dawrah Foot and Mouth Vaccine Institute

which produced botulinum toxin and conducted virus research.

There is some intelligence to suggest that work was also

conducted on anthrax; - al-Fudaliyah Agriculture and Water

Research Centre where Iraq admitted it undertook aflatoxin

production and genetic engineering; - Amariyah Sera and

Vaccine Institute which was used for the storage of

biological agent seed stocks and was involved in genetic

engineering. 3. By the time of the Gulf War Iraq was

producing very large quantities of chemical and biological

agents. From a series of Iraqi declarations to the UN during

the 1990s we know that by 1991 they had produced at

least: - 19,000 litres of botulinum toxin, 8,500 litres of

anthrax, 2,200 litres of aflatoxin and were working on a

number of other agents; The effects of biological

agents Anthrax is a disease caused by the

bacterium Bacillus Anthracis. Inhalation anthrax is the

manifestation of the disease likely to be expected in

biological warfare. The symptoms may vary, but can include

fever and internal bleeding. The incubation period for

anthrax is 1 to 7 days, with most cases occurring within 2

days of exposure. Botulinum toxin is one of the

most toxic substances known to man. The first symptoms of

poisoning may appear as early as 1 hour post exposure or as

late as 8 days after exposure, with the incubation period

between 12 and 22 hours. Paralysis leads to death by

suffocation. Aflatoxins are fungal toxins, which

are potent carcinogens. Most symptoms take a long time to

show. Food products contaminated by aflatoxins can cause

liver inflammation and cancer. They can also affect pregnant

women, leading to stillborn babies and children born with

mutations. Ricin is derived from the castor bean

and can cause multiple organ failure leading to death within

one or two days of inhalation. Page 12 - 2,850 tonnes of

mustard gas, 210 tonnes of tabun, 795 tonnes of sarin and

cyclosarin, and 3.9 tonnes of VX. 4. Iraq’s nuclear

programme was established under the Iraqi Atomic Energy

Commission in the 1950s. Under a nuclear co-operation

agreement signed with the Soviet Union in 1959, a nuclear

research centre, equipped with a research reactor, was built

at Tuwaitha, the main Iraqi nuclear research centre. The

research reactor worked up to 1991. The surge in Iraqi oil

revenues in the early 1970s supported an expansion of the

research programme. This was bolstered in the mid-1970s by

the acquisition of two research reactors powered by highly

enriched uranium fuel and equipment for fuel fabrication and

handling. By the end of 1984 Iraq was self-sufficient in

uranium ore. One of the reactors was destroyed in an Israeli

air attack in June 1981 shortly before it was to become

operational; the other was never completed. 5. By the

mid-1980s the deterioration of Iraq’s position in the war

with Iran prompted renewed interest in the military use of

nuclear technology. Additional resources were put into

developing technologies to enrich uranium as fissile

material (material that makes up the core of a nuclear

weapon) for use in nuclear weapons. Enriched uranium was

preferred because it could be more easily produced covertly

than the alternative, plutonium. Iraq followed parallel

programmes to produce highly enriched uranium (HEU),

electromagnetic isotope separation (EMIS) and gas centrifuge

enrichment. By 1991 one EMIS enrichment facility was nearing

completion and another was under construction. However,

Iraq never succeeded in its EMIS technology and the

programme had been dropped by 1991. Iraq decided to

concentrate on gas centrifuges as the means for producing

the necessary fissile material. Centrifuge facilities were

also under construction, but the centrifuge design was still

being developed. In August 1990 Iraq instigated a crash

programme to develop a single nuclear weapon within a year.

This programme envisaged the rapid development of a small 50

machine gas centrifuge cascade to produce weapons-grade HEU

using fuel from the Soviet research reactor, which was

already substantially enriched, and unused fuel from the

reactor bombed by the Israelis. By the time of the Gulf War,

the crash programme had made little progress. 6. Iraq’s

declared aim was to produce a missile warhead with a

20-kiloton yield and weapons designs were produced for the

simplest implosion weapons. These were similar to the device

used at Nagasaki in 1945. Iraq was also working on more

Effect of a 20-kiloton nuclear detonation A

detonation of a 20-kiloton nuclear warhead over a city might

flatten an area of approximately 3 square miles. Within 1.6

miles of detonation, blast damage and radiation would cause

80% casualties, three-quarters of which would be fatal.

Between 1.6 and 3.1 miles from the detonation, there would

still be 10% casualties. Page 13 advanced concepts. By

1991 the programme was supported by a large body of Iraqi

nuclear expertise, programme documentation and databases and

manufacturing infrastructure. The International Atomic

Energy Agency (IAEA) reported that Iraq had: -

experimented with high explosives to produce implosive shock

waves; - invested significant effort to understand the

various options for neutron initiators; - made significant

progress in developing capabilities for the production,

casting and machining of uranium metal. 7. Prior to the

Gulf War, Iraq had a well-developed ballistic

missile industry. Many of the missiles fired in the

Gulf War were an Iraqi modified version of the SCUD missile,

the al-Hussein, with an extended range of 650km. Iraq had

about 250 imported SCUD-type missiles prior to the Gulf War

plus an unknown number of indigenously produced engines and

components. Iraq was working on other stretched SCUD

variants, such as the al-Abbas, which had a range of 900km.

Iraq was also seeking to reverse-engineer the SCUD engine

with a view to producing new missiles. Recent intelligence

indicates that they may have succeeded at that time. In

particular, Iraq had plans for a new SCUD-derived missile

with a range of 1200km. Iraq also conducted a partial flight

test of a multi-stage satellite launch vehicle based on SCUD

technology, known as the al-Abid. Also during this period,

Iraq was developing the Badr-2000, a 700-1000km range

two-stage solid propellant missile (based on the Iraqi part

of the 1980s CONDOR-2 programme run in co-operation with

Argentina and Egypt). There were plans for 1200–1500km range

solid propellant follow-on systems. The use of

chemical and biological weapons 8. Iraq had made

frequent use of a variety of chemical weapons during the

Iran-Iraq War. Many of the casualties are still in Iranian

hospitals suffering from the long-term effects of numerous

types of cancer and lung diseases. In 1988 Saddam also used

mustard and nerve agents against Iraqi Kurds at Halabja in

northern Iraq (see box on p15). Estimates vary, but

according to Human Rights Watch up to 5,000 people were

killed. SCUD missiles The short-range mobile

SCUD ballistic missile was developed by the Soviet Union in

the 1950s, drawing on the technology of the German V-2

developed in World War II. For many years it was the

mainstay of Soviet and Warsaw Pact tactical missile forces

and it was also widely exported. Recipients of

Soviet-manufactured SCUDs included Iraq, North Korea, Iran,

and Libya, although not all were sold directly by the Soviet

Union. Page 14 9. Iraq used significant quantities of

mustard, tabun and sarin during the war with Iran resulting

in over 20,000 Iranian casualties. A month after the attack

on Halabja, Iraqi troops used over 100 tonnes of sarin

against Iranian troops on the al-Fao peninsula. Over the

next three months Iraqi troops used sarin and other nerve

agents on Iranian troops causing extensive casualties. 10.

From Iraqi declarations to the UN after the Gulf War we know

that by 1991 Iraq had produced a variety of delivery means

for chemical and biological agents including over 16,000

free-fall bombs and over 110,000 artillery rockets and

shells. Iraq also admitted to the UN Special Commission

(UNSCOM) that it had 50 chemical and 25 biological warheads

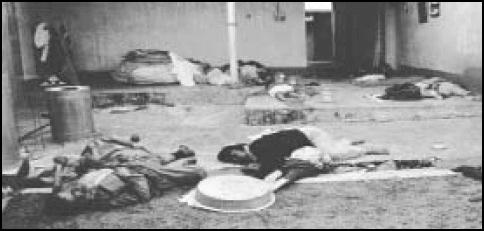

available for its ballistic missiles. The Attack on

Halabja On Friday 17th March 1988 the village of

Halabja was bombarded by Iraqi warplanes. The raid was over

in minutes. Saddam Hussein used chemical weapons against his

own people. A Kurd described the effects of a chemical

attack on another village: “My brothers and my wife had

blood and vomit running from their noses and their mouths.

Their heads were tilted to one side. They were groaning. I

couldn’t do much, just clean up the blood and vomit from

their mouths and try in every way to make them breathe

again. I did artificial respiration on them and then I gave

them two injections each. I also rubbed creams on my wife

and two brothers.” (From “Crimes Against Humanity” Iraqi

National Congress.)

Among the corpses at Halabja,

children were found dead where they had been playing outside

their homes. In places, streets were piled with

corpses. Page 15 The use of ballistic

missiles 11. Iraq fired over 500 SCUD-type missiles at

Iran during the Iran-Iraq War at both civilian and military

targets, and 93 SCUD-type missiles during the Gulf

War. The latter were targeted at Israel and Coalition

forces stationed in the Gulf region. 12. At the end of the

Gulf War the international community was determined that

Iraq’s arsenal of chemical and biological weapons and

ballistic missiles should be dismantled. The method chosen

to achieve this was the establishment of UNSCOM to carry out

intrusive inspections within Iraq and to eliminate its

chemical and biological weapons and ballistic missiles with

a range of over 150km. The IAEA was charged with the

abolition of Iraq’s nuclear weapons programme. Between 1991

and 1998 UNSCOM succeeded in identifying and destroying very

large quantities of chemical weapons and ballistic missiles

as well as associated production facilities. The IAEA also

destroyed the infrastructure for Iraq’s nuclear weapons

programme and removed key nuclear materials. This was

achieved despite a continuous and sophisticated programme of

harassment, obstruction, deception and denial (see Part 2).

Because of this UNSCOM concluded by 1998 that it was unable

to fulfil its mandate. The inspectors were withdrawn in

December 1998. 13. Based on the UNSCOM report to the UN

Security Council in January 1999 and earlier UNSCOM reports,

we assess that when the UN inspectors left Iraq they were

unable to account for: - up to 360 tonnes of bulk chemical

warfare agent, including 1.5 tonnes of VX nerve agent; -

up to 3,000 tonnes of precursor chemicals, including

approximately 300 tonnes which, in the Iraqi chemical

warfare programme, were unique to the production of VX; -

growth media procured for biological agent production

(enough to produce over three times the 8,500 litres of

anthrax spores Iraq admits to having manufactured); - over

30,000 special munitions for delivery of chemical and

biological agents. 14. The departure of UNSCOM meant that

the international community was unable to establish the

truth behind these large discrepancies and greatly

diminished its ability to monitor and assess Iraq’s

continuing attempts to reconstitute its programmes. Page

16 CHAPTER 3 1. This chapter sets out what we

know of Saddam Hussein’s chemical, biological, nuclear and

ballistic missile programmes, drawing on all the available

evidence. While it takes account of the results from UN

inspections and other publicly available information, it

also draws heavily on the latest intelligence about Iraqi

efforts to develop their programmes and capabilities since

1998. The main conclusions are that: - Iraq has a useable

chemical and biological weapons capability, in breach of

UNSCR 687, which has included recent production of chemical

and biological agents; - Saddam continues to attach great

importance to the possession of weapons of mass destruction

and ballistic missiles which he regards as being the basis

for Iraq’s regional power. He is determined to retain these

capabilities; - Iraq can deliver chemical and biological

agents using an extensive range of artillery shells,

free-fall bombs, sprayers and ballistic missiles; - Iraq

continues to work on developing nuclear weapons, in breach

of its obligations under the Non-Proliferation Treaty and in

breach of UNSCR 687. Uranium has been sought from Africa

that has no civil nuclear application in Iraq; - Iraq

possesses extended-range versions of the SCUD ballistic

missile in breach of UNSCR 687 which are capable of reaching

Cyprus, Eastern Turkey, Tehran and Israel. It is also

developing longer-range ballistic missiles; - Iraq’s

current military planning specifically envisages the use of

chemical and biological weapons; - Iraq’s military forces

are able to use chemical and biological weapons, with

command, control and logistical arrangements in place. The

Iraqi military are able to deploy these weapons within 45

minutes of a decision to do so; - Iraq has learnt lessons

from previous UN weapons inspections and is already taking

steps to conceal and disperse sensitive equipment and

documentation in advance of the return of inspectors; -

Iraq’s chemical, biological, nuclear and ballistic missiles

programmes are well-funded. CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL

WEAPONS Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC)

Assessment: 1999–2002 2. Since the withdrawal of the

inspectors the JIC has monitored evidence, including from

secret intelligence, of continuing work on Iraqi offensive

chemical and biological warfare capabilities. In the first

half of 2000 the JIC noted Page 17 intelligence on Iraqi

attempts to procure dual-use chemicals and on the

reconstruction of civil chemical production at sites

formerly associated with the chemical warfare programme.

Iraq had also been trying to procure dual-use materials and

equipment which could be used for a biological warfare

programme. Personnel known to have been connected to the

biological warfare programme up to the Gulf War had been

conducting research into pathogens. There was intelligence

that Iraq was starting to produce biological warfare agents

in mobile production facilities. Planning for the project

had begun in 1995 under Dr Rihab Taha, known to have been a

central player in the pre-Gulf War programme. The JIC

concluded that Iraq had sufficient expertise, equipment and

material to produce biological warfare agents within weeks

using its legitimate bio-technology facilities. 3. In

mid-2001 the JIC assessed that Iraq retained some chemical

warfare agents, precursors, production equipment and weapons

from before the Gulf War. These stocks would enable Iraq

to produce significant quantities of mustard gas within

weeks and of nerve agent within months. The JIC concluded

that intelligence on Iraqi former chemical and biological

warfare facilities, their limited reconstruction and civil

production pointed to a continuing research and development

programme. These chemical and biological capabilities

represented the most immediate threat from Iraqi weapons of

mass destruction. Since 1998 Iraqi development of mass

destruction weaponry had been helped by the absence of

inspectors and the increase in illegal border trade, which

was providing hard currency. 4. In the last six months the

JIC has confirmed its earlier judgements on Iraqi chemical

and biological warfare capabilities and assessed that Iraq

has the means to deliver chemical and biological

weapons. Recent intelligence 5. Subsequently,

intelligence has become available from reliable sources

which complements and adds to previous intelligence and

confirms the JIC assessment that Iraq has chemical and

biological weapons. The intelligence also shows that the

Iraqi leadership has been discussing a number of issues

related to these weapons. This intelligence covers: -

Confirmation that chemical and biological weapons play an

important role in Iraqi military thinking: intelligence

shows that Saddam attaches great importance to the

possession of chemical and biological weapons which he

regards as being the basis for Iraqi regional power. He

believes that respect for Iraq rests on its possession of

these weapons and the missiles capable of delivering them.

Intelligence indicates that Saddam is determined to retain

this capability and recognises that Iraqi political weight

would be diminished if Iraq’s military power rested solely

on its conventional military forces. - Iraqi attempts

to retain its existing banned weapons systems: Iraq is

already taking steps to prevent UN weapons inspectors

finding evidence of Page 18 its chemical and biological

weapons programme. Intelligence indicates that Saddam has

learnt lessons from previous weapons inspections, has

identified possible weak points in the inspections process

and knows how to exploit them. Sensitive equipment and

papers can easily be concealed and in some cases this is

already happening. The possession of mobile biological agent

production facilities will also aid concealment efforts.

Saddam is determined not to lose the capabilities that he

has been able to develop further in the four years since

inspectors left. - Saddam’s willingness to use

chemical and biological weapons: intelligence indicates

that as part of Iraq’s military planning Saddam is willing

to use chemical and biological weapons, including against

his own Shia population. Intelligence indicates that the

Iraqi military are able to deploy chemical or biological

weapons within 45 minutes of an order to do so.

Chemical and biological agents: surviving stocks 6.

When confronted with questions about the unaccounted stocks,

Iraq has claimed repeatedly that if it had retained any

chemical agents from before the Gulf War they would have

deteriorated sufficiently to render them harmless. But Iraq

has admitted to UNSCOM to having the knowledge and

capability to add stabiliser to nerve agent and other

chemical warfare agents which would prevent such

decomposition. In 1997 UNSCOM also examined some munitions

which had been filled with mustard gas prior to 1991 and

found that they remained very toxic and showed little sign

of deterioration. 7. Iraq has claimed that all its

biological agents and weapons have been destroyed. No

convincing proof of any kind has been produced to support

this claim. In particular, Iraq could not explain large

discrepancies between the amount of growth media (nutrients

required for the specialised growth of agent) it procured

before 1991 and the amounts of agent it admits to having

manufactured. The discrepancy is enough to produce more than

three times the amount of anthrax allegedly

manufactured. Chemical agent: production

capabilities 8. Intelligence shows that Iraq has

continued to produce chemical agent. During the Gulf War a

number of facilities which intelligence reporting indicated

were directly or indirectly associated with Iraq’s chemical

weapons effort were attacked and damaged. Following the

ceasefire UNSCOM destroyed or rendered harmless facilities

and equipment used in Iraq’s chemical weapons

programme. Other equipment was released for civilian use

either in industry or academic institutes, where it was

tagged and regularly inspected and monitored, or else placed

under camera monitoring, to ensure that it was not being

misused. This monitoring ceased when UNSCOM withdrew from

Iraq in 1998. However, capabilities remain and, although the

main chemical weapon production facility at al-Muthanna was

completely destroyed by UNSCOM and has not been Page

19 rebuilt, other plants formerly associated with the

chemical warfare programme have been rebuilt. These include

the chlorine and phenol plant at Fallujah 2 near Habbaniyah.

In addition to their civilian uses, chlorine and phenol are

used for precursor chemicals which contribute to the

production of chemical agents. 9. Other dual-use

facilities, which are capable of being used to support the

production of chemical agent and precursors, have been

rebuilt and re-equipped. New chemical facilities have been

built, some with illegal foreign assistance, and are

probably fully operational or ready for production. These

include the Ibn Sina Company at Tarmiyah (see figure 1),

which is a chemical research centre. It undertakes

research, development and production of chemicals previously

imported but not now available and which are needed for

Iraq’s civil industry. The Director General of the

research centre is Hikmat Na’im al-Jalu who prior to the

Gulf War worked in Iraq’s nuclear weapons programme and

after the war was responsible for preserving Iraq’s chemical

expertise. FIGURE 1: THE IBN SINA COMPANY AT

TARMIYAH 10. Parts of the al-Qa’qa’ chemical complex

damaged in the Gulf War have also been repaired and are

operational. Of particular concern are elements of the

phosgene production plant at al-Qa’qa’. These were severely

damaged during the Gulf War, and dismantled under UNSCOM

supervision, but have since been rebuilt. While phosgene

does have industrial uses it can also be used by itself as a

chemical agent or as a precursor for nerve agent. 11. Iraq

has retained the expertise for chemical warfare research,

agent production and weaponisation. Most of the personnel

previously involved in the programme remain in country.

While UNSCOM found a number of technical manuals (so called

“cook books”) for the production of chemical agents and

critical precursors, Iraq’s claim to have unilaterally

destroyed the bulk of the documentation cannot be confirmed

and is almost certainly untrue. Recent intelligence

indicates that Iraq is still discussing methods of

concealing such documentation in order to ensure that it is

not discovered by any future UN inspections. Page 20

Biological agent: production capabilities 12. We know

from intelligence that Iraq has continued to produce

biological warfare agents. As with some chemical equipment,

UNSCOM only destroyed equipment that could be directly

linked to biological weapons production. Iraq also has its

own engineering capability to design and construct

biological agent associated fermenters, centrifuges, sprayer

dryers and other equipment and is judged to be

self-sufficient in the technology required to produce

biological weapons. The Page 21 The Problem of

Dual-Use Facilities Almost all components and supplies

used in weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missile

programmes are dual-use. For example, any major

petrochemical or biotech industry, as well as public health

organisations, will have legitimate need for most materials

and equipment required to manufacture chemical and

biological weapons. Without UN weapons inspectors it is very

difficult therefore to be sure about the true nature of many

of Iraq’s facilities. For example, Iraq has built a large

new chemical complex, Project Baiji, in the desert in north

west Iraq at al-Sharqat (see figure 2). This site is a

former uranium enrichment facility which was damaged during

the Gulf War and rendered harmless under supervision of the

IAEA. Part of the site has been rebuilt, with work starting

in 1992, as a chemical production complex. Despite the

site being far away from populated areas it is surrounded by

a high wall with watch towers and guarded by armed guards.

Intelligence reports indicate that it will produce nitric

acid which can be used in explosives, missile fuel and in

the purification of uranium. FIGURE 2: AL-SHARQAT CHEMICAL

PRODUCTION FACILITY experienced personnel who were active

in the programme have largely remained in the country. Some

dual-use equipment has also been purchased, but without

monitoring by UN inspectors Iraq could have diverted it to

their biological weapons programme. This newly purchased

equipment and other equipment previously subject to

monitoring could be used in a resurgent biological warfare

programme. Facilities of concern include: - the Castor Oil

Production Plant at Fallujah: this was damaged in UK/US air

attacks in 1998 (Operation Desert Fox) but has been rebuilt.

The residue from the castor bean pulp can be used in the

production of the biological agent ricin; - the al-Dawrah

Foot and Mouth Disease Vaccine Institute: which was involved

in biological agent production and research before the Gulf

War; - the Amariyah Sera and Vaccine Plant at Abu Ghraib:

UNSCOM established that this facility was used to store

biological agents, seed stocks and conduct biological

warfare associated genetic research prior to the Gulf War.

It has now expanded its storage capacity. 13. UNSCOM

established that Iraq considered the use of mobile

biological agent production facilities. In the past two

years evidence from defectors has indicated the existence of

such facilities. Recent intelligence confirms that the Iraqi

military have developed mobile facilities. These would help

Iraq conceal and protect biological agent production from

military attack or UN inspection. Chemical and

biological agents: delivery means 14. Iraq has a

variety of delivery means available for both chemical and

biological agents. These include: - free-fall bombs: Iraq

acknowledged to UNSCOM the deployment to two sites of

free-fall bombs filled with biological agent during 1990–91.

These bombs were filled with anthrax, botulinum toxin and

aflatoxin. Iraq also acknowledged possession of four types

of aerial bomb with various chemical agent fills including

sulphur mustard, tabun, sarin and cyclosarin; - artillery

shells and rockets: Iraq made extensive use of artillery

munitions filled with chemical agents during the Iran-Iraq

War. Mortars can also be used for chemical agent delivery.

Iraq is known to have tested the use of shells and rockets

filled with biological agents. Over 20,000 artillery

munitions remain unaccounted for by UNSCOM; - helicopter

and aircraft borne sprayers: Iraq carried out studies into

aerosol dissemination of biological agent using these

platforms prior to 1991. UNSCOM was unable to account for

many of these devices. It is probable that Iraq retains a

capability for aerosol dispersal of both chemical and

biological agent over a large area; - al-Hussein ballistic

missiles (range 650km): Iraq told UNSCOM that it filled 25

warheads with anthrax, botulinum toxin and aflatoxin. Iraq

also Page 22 developed chemical agent warheads for

al-Hussein. Iraq admitted to producing 50 chemical warheads

for al-Hussein which were intended for the delivery of a

mixture of sarin and cyclosarin. However, technical analysis

of warhead remnants has shown traces of VX degradation

product which indicate that some additional warheads were

made and filled with VX; - al-Samoud/Ababil-100 ballistic

missiles (range 150km plus): it is unclear if chemical and

biological warheads have been developed for these systems,

but given the Iraqi experience on other missile systems, we

judge that Iraq has the technical expertise for doing

so; - L-29 remotely piloted vehicle programme (see figure

3): we know from intelligence that Iraq has attempted to

modify the L-29 jet trainer to allow it to be used as an

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) which is potentially capable

of delivering chemical and biological agents over a large

area. Chemical and biological warfare: command and

control 15. The authority to use chemical and

biological weapons ultimately resides with Saddam but

intelligence indicates that he may have also delegated this

authority to his son Qusai. Special Security Organisation

(SSO) and Special Republican Guard (SRG) units would be

involved in the movement of any chemical and biological

weapons to military units. The Iraqi military holds

artillery and missile systems at Corps level throughout the

Armed Forces and conducts regular training with them. The

Directorate of Rocket Forces has operational control of

strategic missile systems and some Multiple Launcher Rocket

Systems. Chemical and biological weapons:

summary 16. Intelligence shows that Iraq has covert

chemical and biological weapons programmes, in breach of UN

Security Council Resolution 687 and has continued to produce

chemical and biological agents. Iraq has: - chemical and

biological agents and weapons available, both from pre-Gulf

War stocks and more recent production; - the capability to

produce the chemical agents mustard gas, tabun, sarin,

cyclosarin, and VX capable of producing mass

casualties; Page 23

FIGURE 3: THE L-29 JET TRAINER - a

biological agent production capability and can produce at

least anthrax, botulinum toxin, aflatoxin and ricin. Iraq

has also developed mobile facilities to produce biological

agents; - a variety of delivery means available; -

military forces, which maintain the capability to use these

weapons with command, control and logistical arrangements in

place. NUCLEAR WEAPONS Joint Intelligence

Committee (JIC) Assessments: 1999–2001 17. Since 1999

the JIC has monitored Iraq’s attempts to reconstitute its

nuclear weapons programme. In mid-2001 the JIC assessed that

Iraq had continued its nuclear research after 1998. The JIC

drew attention to intelligence that Iraq had recalled its

nuclear scientists to the programme in 1998. Since 1998 Iraq

had been trying to procure items that could be for use in

the construction of centrifuges for the enrichment of

uranium. Iraqi nuclear weapons expertise 18.

Paragraphs 5 and 6 of Chapter 2 describe the Iraqi nuclear

weapons programme prior to the Gulf War. It is clear from

IAEA inspections and Iraq’s own declarations that by 1991

considerable progress had been made in both developing

methods to produce fissile material and in weapons design.

The IAEA dismantled the physical infrastructure of the Iraqi

nuclear weapons Elements of a nuclear weapons

programme: nuclear fission weapon A typical nuclear

fission weapon consists of: - fissile material for the

core which gives out huge amounts of explosive energy from

nuclear reactions when made “super critical” through extreme

compression. Fissile material is usually either highly

enriched uranium (HEU) or weapons-grade plutonium: — HEU

can be made in gas centrifuges (see separate box on

p25); — plutonium is made by reprocessing fuel from a

nuclear reactor; - explosives which are needed to compress

the nuclear core. These explosives also require a complex

arrangement of detonators, explosive charges to produce an

even and rapid compression of the core; - sophisticated

electronics to fire the explosives; - a neutron initiator

to provide initial burst of neutrons to start the nuclear

reactions. Page 24 programme, including the dedicated

facilities and equipment for uranium separation and

enrichment, and for weapon development and production, and

removed the remaining highly enriched uranium. But Iraq

retained, and retains, many of its experienced nuclear

scientists and technicians who are specialised in the

production of fissile material and weapons design.

Intelligence indicates that Iraq also retains the

accompanying programme documentation and data. 19.

Intelligence shows that the present Iraqi programme is

almost certainly seeking an indigenous ability to enrich

uranium to the level needed for a nuclear weapon. It

indicates that the approach is based on gas centrifuge

uranium enrichment, one of the routes Iraq was following for

producing fissile material before the Gulf War. But Iraq

needs certain key equipment, including gas centrifuge

components and components for the production of fissile

material before a nuclear bomb could be developed. 20.

Following the departure of weapons inspectors in 1998 there

has been an accumulation of intelligence indicating that

Iraq is making concerted covert efforts to acquire dual-use

technology and materials with nuclear applications. Iraq’s

known holdings of processed uranium are under IAEA

supervision. But there is intelligence that Iraq has sought

the supply of significant quantities of uranium from Africa.

Iraq has no active civil nuclear power programme or nuclear

power plants and therefore has no legitimate reason to

acquire uranium. Gas centrifuge uranium

enrichment Uranium in the form of uranium hexafluoride

is separated into its different isotopes in rapidly spinning

rotor tubes of special centrifuges. Many hundreds or

thousands of centrifuges are connected in cascades to enrich

uranium. If the lighter U235 isotope is enriched to more

than 90% it can be used in the core of a nuclear

weapon. Weaponisation Weaponisation is the

conversion of these concepts into a reliable weapon. It

includes: - developing a weapon design through

sophisticated science and complex calculations; -

engineering design to integrate with the delivery

system; - specialised equipment to cast and machine safely

the nuclear core; - dedicated facilities to assemble the

warheads; - facilities to rigorously test all individual

components and designs; The complexity is much greater for a

weapon that can fit into a missile warhead than for a larger

Nagasaki-type bomb. Page 25 21. Intelligence shows that

other important procurement activity since 1998 has included

attempts to purchase: - vacuum pumps which could be used

to create and maintain pressures in a gas centrifuge cascade

needed to enrich uranium; - an entire magnet production

line of the correct specification for use in the motors and

top bearings of gas centrifuges. It appears that Iraq is

attempting to acquire a capability to produce them on its

own rather than rely on foreign procurement; - Anhydrous

Hydrogen Fluoride (AHF) and fluorine gas. AHF is commonly

used in the petrochemical industry and Iraq frequently

imports significant amounts, but it is also used in the

process of converting uranium into uranium hexafluoride for

use in gas centrifuge cascades; - one large filament

winding machine which could be used to manufacture carbon

fibre gas centrifuge rotors; - a large balancing machine

which could be used in initial centrifuge balancing

work. 22. Iraq has also made repeated attempts covertly to

acquire a very large quantity (60,000 or more) of

specialised aluminium tubes. The specialised aluminium in

question is subject to international export controls because

of its potential application in the construction of gas

centrifuges used to enrich uranium, although there is no

definitive intelligence that it is destined for a nuclear

programme. Nuclear weapons: timelines 23. In

early 2002, the JIC assessed that UN sanctions on Iraq were

hindering the import of crucial goods for the production of

fissile material. The JIC judged Iraq’s civil nuclear

programme - Iraq’s long-standing civil nuclear power

programme is limited to small scale research. Activities

that could be used for military purposes are prohibited by

UNSCR 687 and 715. - Iraq has no nuclear power plants and

therefore no requirement for uranium as fuel. - Iraq has

a number of nuclear research programmes in the fields of

agriculture, biology, chemistry, materials and

pharmaceuticals. None of these activities requires more than

tiny amounts of uranium which Iraq could supply from its own

resources. - Iraq’s research reactors are

non-operational; two were bombed and one was never

completed. Page 26 that while sanctions remain effective

Iraq would not be able to produce a nuclear weapon. If they

were removed or prove ineffective, it would take Iraq at

least five years to produce sufficient fissile material for

a weapon indigenously. However, we know that Iraq retains

expertise and design data relating to nuclear weapons. We

therefore judge that if Iraq obtained fissile material and

other essential components from foreign sources the timeline

for production of a nuclear weapon would be shortened and

Iraq could produce a nuclear weapon in between one and two

years. BALLISTIC MISSILES Joint Intelligence

Committee (JIC) Assessment: 1999–2002 24. In mid-2001

the JIC drew attention to what it described as a

“step-change” in progress on the Iraqi missile programme

over the previous two years. It was clear from intelligence

that the range of Iraqi missiles which was permitted by the

UN and supposedly limited to 150kms was being extended and

that work was under way on larger engines for longer-range

missiles. 25. In early 2002 the JIC concluded that Iraq

had begun to develop missiles with a range of over 1,000kms.

The JIC assessed that if sanctions remained effective the

Iraqis would not be able to produce such a missile before

2007. Sanctions and the earlier work of the inspectors had

caused significant problems for Iraqi missile development.

In the previous six months Iraqi foreign procurement efforts

for the missile programme had been bolder. The JIC also

assessed that Iraq retained up to 20 al-Hussein missiles

from before the Gulf War. The Iraqi ballistic missile

programme since 1998 26. Since the Gulf War, Iraq has

been openly developing two short-range missiles up to a

range of 150km, which are permitted under UN Security

Council Resolution 687. The al-Samoud liquid propellant

missile has been extensively tested and is being deployed to

military units. Intelligence indicates that at least 50 have

been produced. Intelligence also indicates that Iraq has

worked on extending its range to at least 200km in breach of

UN Security Resolution 687. Production of the solid

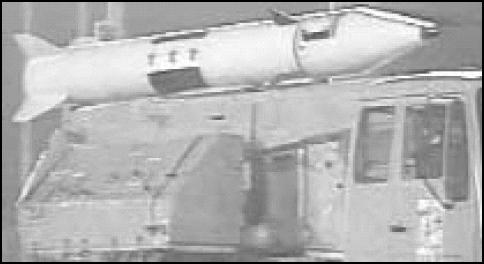

propellant Ababil-100 (Figure 4) is also underway, probably

as an unguided rocket at this stage. There are also plans to

extend its range to at least 200km. Compared to liquid

propellant missiles, those powered by solid Page

27 FIGURE 4: ABABIL-100 propellant offer greater ease of

storage, handling and mobility. They are also quicker to

take into and out of action and can stay at a high state of

readiness for longer periods. 27. According to

intelligence, Iraq has retained up to 20 al-Hussein missiles

(Figure 5), in breach of UN Security Council Resolution 687.

These missiles were either hidden from the UN as complete

systems, or re-assembled using illegally retained engines

and other components. We judge that the engineering

expertise available would allow these missiles to be

maintained effectively, although the fact that at least some

require re-assembly makes it difficult to judge exactly how

many could be available for use. They could be used with

conventional, chemical or biological warheads and, with a

range of up to 650km, are capable of reaching a number of

countries in the region including Cyprus, Turkey, Saudi

Arabia, Iran and Israel. Page 28 FIGURE 5:

AL-HUSSEIN 28. Intelligence has confirmed that Iraq wants

to extend the range of its missile systems to over 1000km,

enabling it to threaten other regional neighbours. This work

began in 1998, although efforts to regenerate the long-range

ballistic missile programme probably began in 1995. Iraq’s

missile programmes employ hundreds of people. Satellite

imagery (Figure 6) has shown a new engine test stand being

constructed (A), which is larger than the current one used

for al-Samoud (B), and that formerly used for testing SCUD

engines (C) which was dismantled under UNSCOM supervision.

This new stand will be capable of testing engines for medium

range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) with ranges over 1000km,

which are not permitted under UN Security Council Resolution

687. Such a facility would not be needed for systems that

fall within the UN permitted range of 150km. The Iraqis have

recently taken measures to conceal activities at this site.

Iraq is also working to obtain improved guidance technology

to increase missile accuracy. Page 29 FIGURE 6:

AL-RAFAH/SHAHIYAT LIQUID PROPELLANT ENGINE STATIC TEST

STAND 29. The success of UN restrictions means the

development of new longer-range missiles is likely to be a

slow process. These restrictions impact particularly on

the: - availability of foreign expertise; - conduct of

test flights to ranges above 150km; - acquisition of

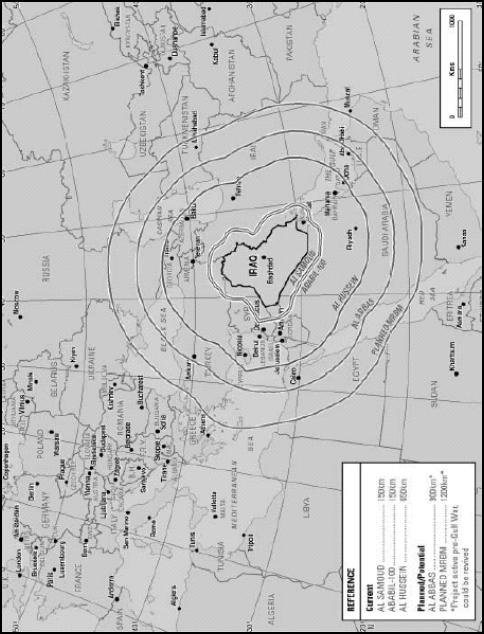

guidance and control technology. 30. Saddam remains

committed to developing longer-range missiles. Even if

sanctions remain effective, Iraq might achieve a missile

capability of over 1000km within 5 years (Figure 7 shows the

range of Iraq’s various missiles). 31. Iraq has managed to

rebuild much of the missile production infrastructure

destroyed in the Gulf War and in Operation Desert Fox in

1998 (see Part 2). New missile-related infrastructure is

also under construction. Some aspects of this, including

rocket propellant mixing and casting facilities at the

al-Mamoun Plant, appear to replicate those linked to the

prohibited Badr-2000 programme (with a planned range of

700–1000km) which were destroyed in the Gulf War or

dismantled by UNSCOM. A new plant at al-Mamoun for

indigenously producing ammonium perchlorate, which is a key

ingredient in the production of solid propellant rocket

motors, has also been constructed. This has been provided

illicitly by NEC Engineers Private Limited, an Indian

chemical engineering firm with extensive links in Iraq,

including to other suspect facilities such as the Fallujah 2

chlorine plant. After an extensive investigation, the Indian

authorities have recently suspended its export licence,

although other individuals and companies are still illicitly

procuring for Iraq. 32. Despite a UN embargo, Iraq has

also made concerted efforts to acquire additional production

technology, including machine tools and raw materials, in

breach of UN Security Council Resolution 1051. The embargo

has succeeded in blocking many of these attempts, such as

requests to buy magnesium powder and ammonium chloride. But

we know from intelligence that some items have found their

way to the Iraqi ballistic missile programme. More will

inevitably continue to do so. Intelligence makes it clear

that Iraqi procurement agents and front companies in third

countries are seeking illicitly to acquire propellant

chemicals for Iraq’s ballistic missiles. This includes

production level quantities of near complete sets of solid

propellant rocket motor ingredients such as aluminium

powder, ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl terminated

polybutadiene. There have also been attempts to acquire

large quantities of liquid propellant chemicals such as

Unsymmetrical Dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) and

diethylenetriamene. We judge these are intended to support

production and deployment of the al-Samoud and development

of longer-range systems. Page 30 Page 31 FIGURE 7:

CURRENT AND PLANNED/POTENTIAL BALLISTIC MISSILES

FUNDING FOR THE WMD PROGRAMME 33. The UN has sought to

restrict Iraq’s ability to generate funds for its chemical,

biological and other military programmes. For example, Iraq

earns money legally under the UN Oil For Food Programme

(OFF) established by UNSCR 986, whereby the proceeds of oil

sold through the UN are used to buy humanitarian supplies

for Iraq. This money remains under UN control and cannot be

used for military procurement. However, the Iraqi regime

continues to generate income outside UN control either in

the form of hard currency or barter goods (which in turn

means existing Iraqi funds are freed up to be spent on other

things). 34. These illicit earnings go to the Iraqi

regime. They are used for building new palaces, as well as

purchasing luxury goods and other civilian goods outside the

OFF programme. Some of these funds are also used by Saddam

Hussein to maintain his armed forces, and to develop or

acquire military equipment, including for chemical,

biological, nuclear and ballistic missile programmes. We do

not know what proportion of these funds is used in this way.

But we have seen no evidence that Iraqi attempts to develop

its weapons of mass destruction and its ballistic missile

programme, for example through covert procurement of

equipment from abroad, has been inhibited in any way by lack

of funds. The steady increase over the last three years in

the availability of funds will enable Saddam to progress the

programmes faster. Iraq’s illicit earnings

Year Amount in $billions 1999 0.8 to 1 UN Sanctions UN

sanctions on Iraq prohibit all imports to and exports from

Iraq. The UN must clear any goods entering or leaving. The

UN also administers the Oil for Food (OFF) programme. Any

imports entering Iraq under the OFF programme are checked

against the Goods Review List for potential military or

weapons of mass destruction utility. Page 32 1. During the 1990s, beginning

in April 1991 immediately after the end of the Gulf War, the

UN Security Council passed a series of resolutions [see box]

establishing the authority of UNSCOM and the IAEA to carry

out the work of dismantling Iraq’s arsenal of chemical,

biological and nuclear weapons programmes and long-range

ballistic missiles. These resolutions were passed under

Chapter VII of the UN Charter which is the instrument that

allows the UN Security Council to authorise the use of

military force to enforce its resolutions. 2. As outlined

in UNSCR 687, Iraq’s chemical, biological and nuclear

weapons programmes were also a breach of Iraq’s commitments

under: - The 1925 Geneva Protocol which bans the use of

chemical and biological weapons; UN Security Council

Resolutions relating to Weapons of Mass

Destruction UNSCR 687, April 1991 created the

UN Special Commission (UNSCOM) and required Iraq to accept,

unconditionally, “the destruction, removal or rendering

harmless, under international supervision” of its chemical

and biological weapons, ballistic missiles with a range

greater than 150km, and their associated programmes, stocks,

components, research and facilities. The International

Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was charged with abolition of

Iraq’s nuclear weapons programme. UNSCOM and the IAEA must

report that their mission has been achieved before the

Security Council can end sanctions. They have not yet done

so. UNSCR 707, August 1991, stated that Iraq must

provide full, final and complete disclosure of all its

programmes for weapons of mass destruction and provide

unconditional and unrestricted access to UN inspectors. For

over a decade Iraq has been in breach of this resolution.

Iraq must also cease all nuclear activities of any kind

other than civil use of isotopes. UNSCR 715, October

1991 approved plans prepared by UNSCOM and IAEA for the

ongoing monitoring and verification (OMV) arrangements to

implement UNSCR 687. Iraq did not accede to this until

November 1993. OMV was conducted from April 1995 to 15

December 1998, when the UN left Iraq. UNSCR 1051,

March 1996 stated that Iraq must declare the shipment

of dual-use goods which could be used for mass destruction

weaponry programmes. Page 33 - the Biological and Toxin

Weapons Convention which bans the development, production,

stockpiling, acquisition or retention of biological

weapons; - the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty which

prohibits Iraq from manufacturing or otherwise acquiring

nuclear weapons. 3. UNSCR 687 obliged Iraq to provide

declarations on all aspects of its weapons of mass

destruction programmes within 15 days and accept the

destruction, removal or rendering harmless under

international supervision of its chemical, biological and

nuclear programmes, and all ballistic missiles with a range

beyond 150km. Iraq did not make a satisfactory declaration

within the specified time-frame. Iraq accepted the UNSCRs

and agreed to co-operate with UNSCOM. The history of the UN

weapons inspections was characterised by persistent Iraqi

obstruction. Iraqi Non-Co-operation with the

Inspectors 4. The former Chairman of UNSCOM, Richard

Butler, reported to the UN Security Council in January 1999

that in 1991 a decision was taken by a high-level Iraqi

Government committee to provide inspectors with only a

portion of its proscribed weapons, components, production

capabilities and stocks. UNSCOM concluded that Iraqi

policy was based on the following actions: - to provide

only a portion of extant weapons stocks, releasing for

destruction only those that were least modern; - to retain

the production capability and documentation necessary to

revive programmes when possible; - to conceal the full

extent of its chemical weapons programme, including the VX

nerve agent project; to conceal the number and type of

chemical and biological warheads for proscribed long-range

missiles; - and to conceal the existence of its biological

weapons programme. 5. In December 1997 Richard Butler

reported to the UN Security Council that Iraq had created a

new category of sites, “Presidential” and “sovereign”, from

which it claimed that UNSCOM inspectors would henceforth be

barred. The terms of the ceasefire in 1991 foresaw no such

limitation. However, Iraq consistently refused to allow

UNSCOM inspectors access to any of these eight Presidential

sites. Many of these so-called “palaces” are in fact large

compounds which are an integral part of Iraqi

counter-measures designed to hide weapons material (see

photograph on p35). UNSCOM and the IAEA were given the

remit to designate any locations for inspection at any time,

review any document and interview any scientist, technician

or other individual and seize any prohibited items for

destruction. Page 34 Page 35 A photograph of a

“presidential site” or what have been called

“palaces”. The total area taken by Buckingham Palace and

its grounds has been superimposed to demonstrate their

comparative size Boundary of presidential site Page

36 Iraq’s policy of deception Iraq has admitted

to UNSCOM to having a large, effective, system for hiding

proscribed material including documentation, components,

production equipment and possibly biological and chemical

agents and weapons from the UN. Shortly after the adoption

of UNSCR 687 in April 1991, an Administrative Security

Committee (ASC) was formed with responsibility for advising

Saddam on the information which could be released to UNSCOM

and the IAEA. The Committee consisted of senior Military

Industrial Commission (MIC) scientists from all of Iraq’s

weapons of mass destruction programmes. The Higher Security

Committee (HSC) of the Presidential Office was in overall

command of deception operations. The system was directed

from the very highest political levels within the

Presidential Office and involved, if not Saddam himself, his

youngest son, Qusai. The system for hiding proscribed

material relies on high mobility and good command and

control. It uses lorries to move items at short notice and

most hide sites appear to be located close to good road

links and telecommunications. The Baghdad area was

particularly favoured. In addition to active measures to

hide material from the UN, Iraq has attempted to monitor,

delay and collect intelligence on UN operations to aid its

overall deception plan. Intimidation 6. Once

inspectors had arrived in Iraq, it quickly became apparent

that the Iraqis would resort to a range of measures

(including physical threats and psychological intimidation

of inspectors) to prevent UNSCOM and the IAEA from

fulfilling their mandate. 7. In response to such

incidents, the President of the Security Council issued

frequent statements calling on Iraq to comply with its

disarmament and monitoring obligations.

8. Iraq denied that it had pursued a

biological weapons programme until July 1995. In July

1995, Iraq acknowledged that biological agents had been

produced on an industrial scale at al-Hakam. Following the

defection in August 1995 of Hussein Kamil, Saddam’s

son-in-law and former Director of the Military

Industrialisation Commission, Iraq released over 2 million

documents relating to its mass destruction weaponry

programmes and acknowledged that it had Iraqi

obstruction of UN weapons inspection teams - firing

warning shots in the air to prevent IAEA inspectors from

intercepting nuclear related equipment (June 1991); -

keeping IAEA inspectors in a car park for 4 days and

refusing to allow them to leave with incriminating documents

on Iraq’s nuclear weapons programme (September 1991); -

announcing that UN monitoring and verification plans were

“unlawful” (October 1991); - refusing UNSCOM inspectors

access to the Iraqi Ministry of Agriculture. Threats were

made to inspectors who remained on watch outside the

building. The inspection team had reliable evidence that the

site contained archives related to proscribed

activities; - in 1991–2 Iraq objected to UNSCOM using its

own helicopters and choosing its own flight plans. In

January 1993 it refused to allow UNSCOM the use of its own

aircraft to fly into Iraq; - refusing to allow UNSCOM to

install remote-controlled monitoring cameras at two key

missile sites (June-July 1993); - repeatedly denying

access to inspection teams (1991- December 1998); -

interfering with UNSCOM’s helicopter operations, threatening

the safety of the aircraft and their crews (June 1997); -

demanding the end of U2 overflights and the withdrawal of US

UNSCOM staff (October 1997); - destroying documentary

evidence of programmes for weapons of mass destruction

(September 1997). Page 37 pursued a biological programme

that led to the deployment of actual weapons. Iraq

admitted producing 183 biological weapons with a reserve of

agent to fill considerably more. 9. Iraq tried to obstruct

UNSCOM’s efforts to investigate the scale of its biological

weapons programme. It created forged documents to account

for bacterial growth media, imported in the late 1980s,

specifically for the production of anthrax, botulinum toxin

and probably plague. The documents were created to indicate

that the material had been imported by the State Company for

Drugs and Medical Appliances Marketing for use in hospitals

and distribution to local authorities. Iraq also censored

documents and scientific papers provided to the first UN

inspection team, removing all references to key individuals,

weapons and industrial production of agents.

Inspection of Iraq’s biological weapons programme In the

course of the first biological weapons inspection in August

1991, Iraq claimed that it had merely conducted a military

biological research programme. At the site visited,

al-Salman, Iraq had removed equipment, documents and even

entire buildings. Later in the year, during a visit to the

al-Hakam site, Iraq declared to UNSCOM inspectors that the

facility was used as a factory to produce proteins derived

from yeast to feed animals. Inspectors subsequently

discovered that the plant was a central site for the

production of anthrax spores and botulinum toxin for

weapons. The factory had also been sanitised by Iraqi

officials to deceive inspectors. Iraq continued to develop

the al-Hakam site into the 1990s, misleading UNSCOM about

its true purpose. Another key site, the Foot and Mouth

Disease Vaccine Institute at al-Dawrah which produced

botulinum toxin and probably anthrax was not divulged as

part of the programme. Five years later, after intense

pressure, Iraq acknowledged that tens of tonnes of

bacteriological warfare agent had been produced there and at

al-Hakam. As documents recovered in August 1995 were

assessed, it became apparent that the full disclosure

required by the UN was far from complete. Successive

inspection teams went to Iraq to try to gain greater