Mapping volcanic ash fall for all weathers

16 August 2018

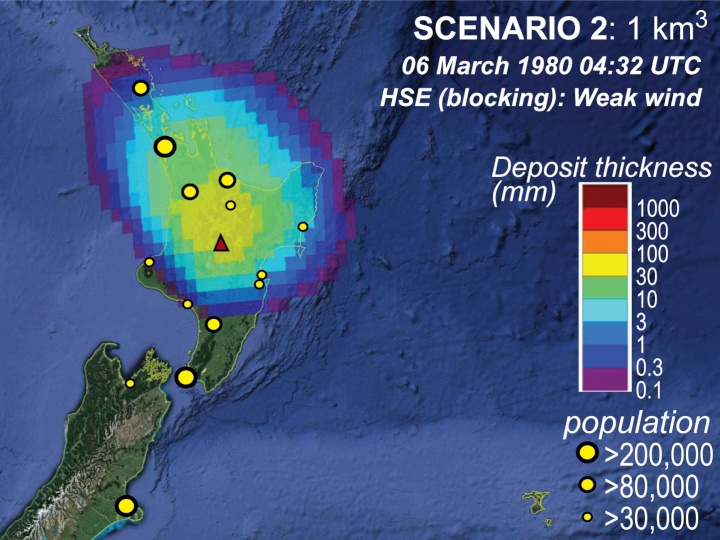

Research funded by the Earthquake Commission (EQC) has developed a way of calculating where the ash from a volcano is most likely to fall, and its thickness, in different parts of New Zealand.

Research team leader Dr. Simon Barker, from Victoria University of Wellington, says that the research involves a complicated calculation of volcanology, geology and meteorology.

“Volcanic ash is magma that has come to the surface and exploded into tiny particles of glass and crystals. Part of modelling the ash fall is to understand how big those fragments are likely to be and where they will move through the atmosphere,” says Dr. Barker.

“We based our work on the giant Taupō volcano. Its explosion was so big around 25,000 years ago that instead of forming a cone, it left a giant hole in the earth’s crust – now partly filled by Lake Taupō. There’s already been a huge amount of study on this volcano, so we had a good idea of the size and type of eruption that could happen in the future.

“We created scenarios based on different eruption sizes, spanning several orders of magnitude in volume, added in the weather data, and ran each scenario 1000 times to see where the ash would fall, and how thick the resulting deposits will be.”

Dr. Barker says that weather conditions and wind direction is a big factor in calculating the direction of the ash fall.

“A westerly will blow the ash over Hawke’s Bay and out to sea, and a southerly will blow it up towards Auckland. Another factor is the shape of the volcanic ash cloud – the ranges are from a weaker “bent” cloud like from Ruapehu in 1995 to the massive “umbrella” cloud that can blast more than 20km up into the stratosphere. This means that we need to include wind at different altitudes in the calculation.

“By adding in the interaction with the weather systems, we can also work out how long it will take for the ash to start falling in different locations. This kind of information can help emergency managers work out which areas need immediate evacuation. For instance in a large Taupō explosion, in the most common westerly weather pattern, it would take about three hours for the ash to reach Napier.”

Dr. Barker says that one of the major benefits of the research so far has been the close work between scientists in New Zealand and the US Geological Survey.

“We’ve been able to use a 3D ash fall model from the USA and add our knowledge about past eruptions from Taupō, which has been great for us and the US-based researchers in testing ideas on large explosive eruptions. This collaboration will also let us model what could happen with other volcanoes in New Zealand and this software could play a major role in eruption forecasting.”

EQC Manager Research Strategy and Investment, Richard Smith, says Dr. Barker’s work has made a significant advance in helping understand the impact that volcanic activity would have on regions across the country.

“The research has developed a model to shows where in New Zealand would be at risk of ash fall that could affect buildings, farms and people under different volcanic eruption scenarios. This is a big help for emergency management planning and risk reduction activity,” says Dr. Smith.

ends

Te Runanga o Ngati Hinemanu: First Marae Based Fresh Water Testing Science Lab Grand Opening 16-17 May 2025

Te Runanga o Ngati Hinemanu: First Marae Based Fresh Water Testing Science Lab Grand Opening 16-17 May 2025 Raise Communications: NZ Careers Expo Kicks Off National Tour Amid Record Unemployment

Raise Communications: NZ Careers Expo Kicks Off National Tour Amid Record Unemployment Hugh Grant: How To Build Confidence In The Data You Collect

Hugh Grant: How To Build Confidence In The Data You Collect Tourism Industry Aotearoa: TRENZ 2026 Set To Rediscover Auckland As It Farewells Rotorua - The Birthplace Of Tourism

Tourism Industry Aotearoa: TRENZ 2026 Set To Rediscover Auckland As It Farewells Rotorua - The Birthplace Of Tourism NIWA: Students Representing New Zealand At The ‘Olympics Of Science Fairs’ Forging Pathway For International Recognition

NIWA: Students Representing New Zealand At The ‘Olympics Of Science Fairs’ Forging Pathway For International Recognition Coalition to End Big Dairy: Activists Protest NZ National Dairy Industry Awards Again

Coalition to End Big Dairy: Activists Protest NZ National Dairy Industry Awards Again