Study of NZ's lost world through fossil bone DNA

Study gives picture of New Zealand’s lost world

through fossil bone DNA

New Zealand’s unique and relatively short

history coupled with new and revealing techniques examining

ancient DNA from fossil bone fragments has provided insights

about the impact of humans on the environment.

On every continent that humans have settled since leaving Africa, extinctions have occurred – from woolly rhinos and mammoth in Europe to giant wombats and marsupial lions in Australia. In most places the exact causes of these extinctions are challenging to identify, because of the vast stretches of time that have passed since it happened.

However, in New Zealand, the last major landmass to be settled by humans, the level of detail in which researchers can study the first contact between people and fauna is exceptionally high because it only happened around 750 years ago.

The study; Subsistence practices, past biodiversity, and anthropogenic impacts revealed by New Zealand-wide ancient DNA survey, which is due to be published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences was led by researchers from Curtin University in Perth, Australia, including study leader Distinguished Research Fellow Professor Michael Bunce, with assistance from academics from University of Otago, Canterbury Museum and Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

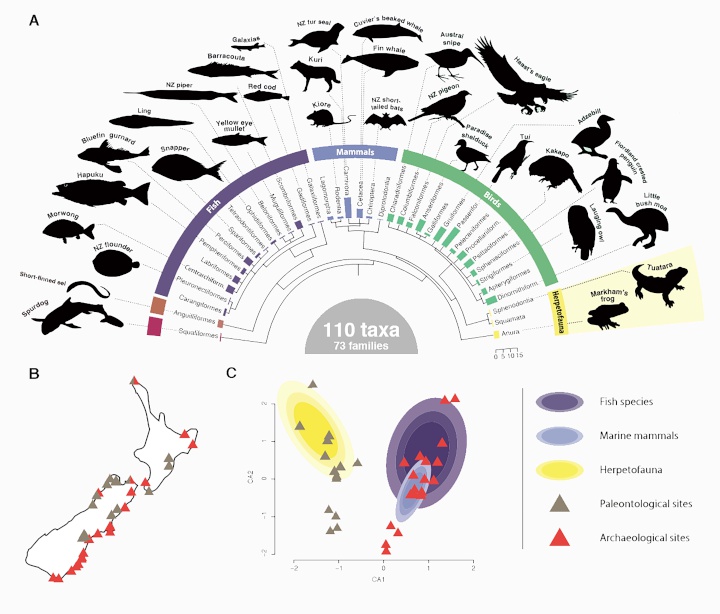

The study characterised DNA preserved in fragmented unidentifiable bone from across New Zealand. Traditionally, research on the biodiversity of the past has revolved around well preserved bone fossils, which are used to characterise extinct species. However, only very few bones from excavations are whole, and many are so damaged that they are of no use to researchers. This means that a very large proportion of the pieces in the jigsaw puzzle has been left unused.

Otago’s Zoology, Anthropology and Archaeology, and Anatomy Departments supported the Curtin researchers by providing bone samples, expertise in the palaeontological/fossil and archaeological context, and interpretation of results.

“This new technology has revealed aspects of the past that until now have been hidden, and will become an important tool in future studies reconstructing early New Zealand,” says Dr Nic Rawlence of the University of Otago’s Department of Zoology.

By comparing bones excavated from caves that predate human arrival, with bones from ancient human kitchen waste (or middens), the researchers characterised the biodiversity that has been lost in New Zealand.

PhD candidate Frederik Seersholm, from Curtin’s School of Molecular and Life Sciences, said he was most surprised by the sheer number of different species able to be identified through the study.

“We found DNA from over a 100 different species and of these, 14 are extinct today,” Mr Seersholm said.

“Our results demonstrate that certain species tend to be missed by traditional morphological methods. For example, we identify species of eel and whales in Māori middens which are rarely identified using traditional midden analysis”.

Professor Richard Walter from the University of Otago’s Department of Anthropology and Archaeology believes the new methods provide much more than just an insight into diet.

“They allow archaeologists to model patterns of early

Māori mobility, seasonal behaviour patterns, and resource

management strategies,” adds Professor

Walter.

Professor Bunce said the researchers sequenced

genetic signatures to identify different species and to

characterise different genetic lineages within one

species.

“For the ground dwelling parrot, the kākāpō, surprisingly high amounts of genetic diversity was detected in the bone fragments,” Professor Bunce said.

“Of the ten kākāpō lineages we identified, only one is still around today and this is an indication of the amount of biodiversity lost from one of New Zealand’s iconic flightless birds,” adds Professor Bunce.

Otago’s Nic Rawlence says the data uncovered in the study highlights the considerable impact humans have had on New Zealand’s biodiversity since settling here around 750 years ago.

“Contrary to previous studies, we have shown that Polynesians/Māori had a significant detrimental impact on the genetic diversity of kakapo” Dr Rawlence adds.

“The genetic signatures of dolphins and small whales in the same sites, along with putative bone harpoon hooks, suggests Polynesians/Māori may have hunted these species, while the presence of large whales no doubt reflects scavenging of beached carcasses,” Dr Rawlence says.

According to Mr Seersholm, the findings demonstrate how much information is stored in seemingly insignificant bone fragments. With support from the Australian Research Council and The Forrest Research Foundation the Curtin researchers aim at expanding the study to other parts of the world.

“There is without doubt a great deal of information to be retrieved from fragmented bones, and it is likely that important future discoveries on extinct species and past biodiversity are hidden in neglected excavation bags in the basements of museums and universities around the globe.” Mr Seersholm said.

Thrive Whanganui: Empowering Entrepreneurs With Disabilities - Launching February 2025

Thrive Whanganui: Empowering Entrepreneurs With Disabilities - Launching February 2025 Primeproperty Group: Primeproperty Group Purchases The Reading Cinema Complex & Adjoining Car Parking Properties in the heart of Wellington's Courtenay Place

Primeproperty Group: Primeproperty Group Purchases The Reading Cinema Complex & Adjoining Car Parking Properties in the heart of Wellington's Courtenay Place Hugh Grant: Lessons From Australia - How Digital Tools Could Support NZ Nurses In Palliative Care

Hugh Grant: Lessons From Australia - How Digital Tools Could Support NZ Nurses In Palliative Care Canterbury Museum: Dinosaur Dolphins Survived In New Zealand Long After Extinction Elsewhere

Canterbury Museum: Dinosaur Dolphins Survived In New Zealand Long After Extinction Elsewhere Retail NZ: Retailers Still Under Pressure At End Of 2024

Retail NZ: Retailers Still Under Pressure At End Of 2024  University of Canterbury: Research Sheds Light On Fire Risk For Canterbury

University of Canterbury: Research Sheds Light On Fire Risk For Canterbury