Daylight Robbery

Whilst it is acknowledged that the proposed Medium Density Residential Standards outlined in the Resource Management (Enabling Housing Supply and Other Matters) Amendment Bill will increase housing growth in cities across New Zealand, these standards could come at a very high cost for some occupants of adjacent properties.

It is important that New Zealanders understand what these costs are, even if they agree that such costs are acceptable in the pursuit of housing affordability.

There is nothing in New Zealand legislation which safeguards the amount of sunlight a property receives post-construction. Historically, many Councils provided a high level of protection to the sun lighting of adjacent properties through the use of building standards contained in District Plans, which created a building shape that could be built without the need for resource consent.

For several years there has been significant pressure placed on Councils to amend these standards to allow taller and larger residential buildings to be built without the need for resource consent, or the ability of neighbours to influence the development.

The extent of change proposed in the Medium Density Residential Standards are dramatically different from existing rules applying to many urban areas, and suburban areas in particular. There is considerable potential for ‘daylight robbery’, in terms of occupants of adjacent properties experiencing a significant loss of winter sun and summer evening sun. The new standards are proposed to apply to all residential zones in Tier 1 Councils from August 2022. For the Wellington region, the standards would apply to almost all land with a residential zoning stretching from the edge of the Wellington CBD to the urban limits of the Hutt Valley and Kapiti Coast.

The standards that have the greatest effect on sun lighting available to adjacent properties are the:

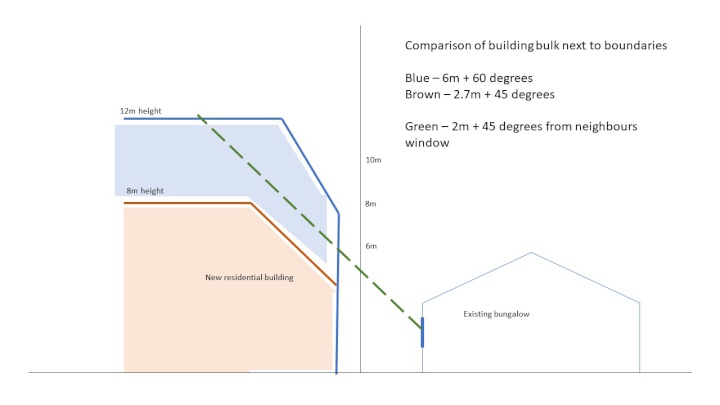

- Height in relation to boundary rule (which typically requires taller parts of buildings to be set further back from a common property boundary) of 6m + 60 degrees;

- Height limit of 12m; and

- Setbacks for side and rear boundaries of 1m.

The shape created by these standards is best understood through visual means. I have calculated that these standards would allow for 7.5m tall structure to be positioned just 1m from a side/rear boundary, with a full 12m height achievable at 3.5m from the boundary.

The diagram below provides a visual comparison of a typical bungalow for a suburban location, next to a new building which complies with existing standards used by Upper Hutt Council of 2.7m + 45 degrees with an 8m building height (shown in brown) with the proposed medium density residential standards (shown in blue). The additional building bulk provided for, is considerable. A green line is also drawn from the window of the existing dwelling at a 45-degree angle. In the example, the window on the existing dwelling is setback 3m from the common property boundary.

Figure - Comparing Building Bulk adjacent Property Boundary

In this example, the facing window in the bungalow would continue to receive a good degree of sun lighting over the majority of the calendar year, if the adjacent building complied with the existing Upper Hutt standard. However, the same window is anticipated to receive little direct sunlight between April and August or after 3pm in summer, if the adjacent building goes above the green line.

This is because the elevation of the sun significantly drops in the sky over the colder months, and increases the chances of taller buildings obstructing the path of the sun. Even in the warmest months of December and January, the sun only achieves an elevation of 45 degrees or more between the hours of 9am and 3pm. Further sun lighting issues could be caused by overshadowing.

It is reasonable for residents of existing dwellings to want to retain direct sunlight, particularly over the winter months, and existing design guidance in Australia and New Zealand supports the provision of at least two hours of sunlight per day for dwellings.

The 2020 New South Wales ‘Low Rise Housing Diversity Design Guide for Complying Development’ outlines a requirement for new two-storey terrace housing to retain 3 hours of direct sunlight per day to living rooms on abutting lots, where living rooms on adjacent properties are setback more than 3m from the property boundary.

The Victorian Planning Scheme also includes provisions explicitly designed to provide protection to the daylight received by existing windows, particularly on the northern elevation.

The amount of direct solar access a site, and in particular the interior of a home receives, has wide-ranging effects that extend far beyond the creation of a pleasant internal space. A reduction in passive solar heating often results in a drop in internal room temperatures, unless other heat sources are used with associated power costs. Some homes, particularly older homes with poor insulation, will feel colder and damper, and could experience more mould growth. It is also likely to reduce natural illumination levels within the home and increase the need for artificial lighting during daylight hours. Outside the home, reductions in direct sunlight can reduce the ability to dry clothes outside and grow food crops.

NZ Architect and Urban Designer, Graham McIndoe correctly pointed out in 2015 that “Daylight is fundamental to the liveability and internal amenity of interiors, and a significant contributor to the quality of life of its occupants”.

Potential sun lighting effects do vary for different properties and it is agreed that some rooms are more important than others. Single storey dwellings with windows close to property boundaries are at particular risk. Existing dwellings could also be affected by new development along more than one boundary.

The proposed medium density standards have the potential to result in existing suburban homes with good solar access, losing almost all direct sunlight over winter. Is this a cost we are prepared to pay?

Note: Whilst I have tried to draw the diagram to-scale, some distortion of scale may have occurred.

Alison Tindale is a member of the New Zealand Planning Institute, although her views expressed in this article are her own. She has worked as a planning officer in multiple countries.

Gordon Campbell: On Why The Regulatory Standards Bill Should Be Dumped

Gordon Campbell: On Why The Regulatory Standards Bill Should Be Dumped Inland Revenue Department: Tax Assessment Period A Prime Time For Scams, Expert Warns

Inland Revenue Department: Tax Assessment Period A Prime Time For Scams, Expert Warns Students Against Dangerous Driving: SADD And AA Celebrate 40 Years Of Tackling Youth Harm On NZ Roads

Students Against Dangerous Driving: SADD And AA Celebrate 40 Years Of Tackling Youth Harm On NZ Roads NZ Labour Party: Timid Tariff Response Fails New Zealanders

NZ Labour Party: Timid Tariff Response Fails New Zealanders NZ National Party: National Party Bill To Crackdown On Anti-social Behaviour

NZ National Party: National Party Bill To Crackdown On Anti-social Behaviour Te Whariki Manawahine o Hauraki: 'No One Came' - How Māori Communities Were Abandoned During Cyclone Gabrielle

Te Whariki Manawahine o Hauraki: 'No One Came' - How Māori Communities Were Abandoned During Cyclone Gabrielle Government: WorkSafe Makes Significant Shift To Rebalance Its Activities, Launches Road Cone Hotline

Government: WorkSafe Makes Significant Shift To Rebalance Its Activities, Launches Road Cone Hotline