NZCPR-Weekly Have Your Say On The Future Of The Maori Seats

New Zealand Centre For Political Research

Dear Reader,

This week we examine the Maori seats and the Maori Electoral Option, our NZCPR Guest Commentator Graeme Edgeler raises concerns about how 'imputation' increases the number of Maori seats, and our poll asks whether the Maori seats should be retained or abolished.

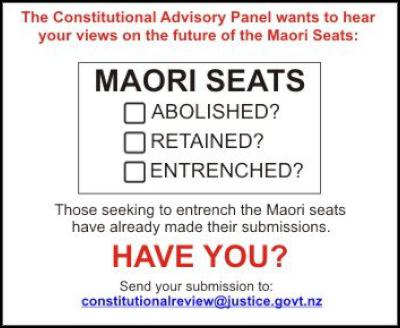

The future of the Maori seats is a key issue in the government's constitutional review. Advocates of entrenching the Maori seats will have made their submissions in force. Have you? If you believe the time has come to abolish the Maori seats, then please make your opinion count by sending in a submission to the Constitutional Advisory Panel at constitutionalreview@justice.govt.nz.

Below is a simple message for promoting through networks. The Advisory Panel says it has received 1500 submissions, but we know that hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders are concerned about the issues that are up for review. Please help us to raise awareness and encourage submissions on a review that has the potential to change the future direction of New Zealand - permanently.

Thanks so much for your interest and support.

Kindest regards,

Dr Muriel

Newman

NZCPR Founder and Director

What’s new on our Breaking Views blog…

Peter

Saunders: The moral case for a smaller state

Richard

Epstein: In Defense of the NSA

Mike

Butler: No-vote and Maori seats relevance

Reuben

Chapple: Immigration Concretes

NZCPR

Weekly:

HAVE YOUR SAY ON THE FUTURE

OF THE MAORI SEATS

By Dr Muriel Newman

As

expected, Saturday’s Ikaroa-Rawhiti by-election,

forced

by the death in April of sitting Labour Party MP and former

Cabinet Minister Parekura Horomia, was won by the Labour

Party’s Meka Whaitiri. She took 4368 votes, the Mana

Party’s Te Hamua Nikora 2607, the Maori Party’s Na

Raihania 2104, the Green Party’s Marama Davidson 1188, the

Aotearoa Legalise Cannabis Party’s Michael Appleby 161,

and the Independents Maurice Wairau and Adam Holland, 27 and

13 votes respectively.

The dismal third-place showing by the Maori Party has been blamed, not only on the long-running leadership wrangle between Pita Sharples and Te Ururoa Flavell, but also on a growing belief that the Maori Party has lost touch with all but the iwi elite. This has resulted in the far-left leaning Mana Party picking up support, prompting leader Hone Harawira to suggest that the Maori Party join Mana in order to hold onto the Maori seats. But quite how the extremist Mana Party could possibly reach an accommodation with the elite Maori Party is not clear, although it does seem likely that the Maori Party will take on a more radical appearance in the future under a new leadership regime, than it has had in the past through the more benign-looking (yet no less radical) leadership of Pita Sharples and Tariana Turia.

The Labour Party has meanwhile declared war on the two race-based parties, as it fights to win back the Maori seats. Back in January at the annual Ratana Pa celebration, Labour Leader David Shearer stated: “I think the Maori seats are up for grabs and we are going for broke to get them. We are in competition with the Maori Party and Mana and we are determined to win the Maori seats back.”

The Maori seats, of course, had their origin in 1867 as a temporary measure to give Maori men the vote. The 1852 New Zealand Constitution Act to introduce representative government established voting rights based on the same individual property qualification that existed in Britain. The right to vote was conferred to males over the age of 21 who held a freehold estate to the value of 100 pounds, or a leasehold estate to the value of 10 pounds, or a tenement within a town to the value of 10 pounds, or if not within a town a tenement to the value of five pounds. That meant only Maori males over the age of 21 who held a freehold or leasehold estate or tenement of the specified minimum value could exercise the right to vote. Those who held communal land holdings had to ‘individualise’ them by converting them into Crown grants to gain the right to vote.[1]

Over the ensuing years many attempts were made to increase Maori representation, culminating in the 1867 Maori Representation Act, which established four temporary Maori electorates for a period of five years – three in the North Island and one in the South - for Maori men over the age of 21. The task of individualising Maori land tenure proved to be more difficult than expected, and so the temporary provisions - which contained no property qualification at all - were extended for a further five years, and then in 1876, they were extended indefinitely.

The property ownership voting qualification for all men was finally removed in 1879, which meant, in effect, that Maori men had gained universal voting rights 12 years earlier than European men. At that stage the temporary Maori seats were no longer needed, and with the introduction of universal suffrage in 1893, any practical reason for separate Maori seats disappeared completely.

The 1986 Royal Commission on the Electoral System, which recommended that MMP replace FPP as New Zealand’s voting system, also recommended the abolition of the Maori seats on the basis that MMP would adequately increase the Parliamentary representation of minority groups including Maori.

When the MMP legislation was introduced into the House, it contained no provision for separate Maori representation. However, Maori leaders gathered at Turangawaewae and planned a campaign to not only retain the Maori seats, but to increase their numbers. Their success means that Maori are now over-represented in Parliament relative to their proportion in the population. At present 23 of the current 121 MPs – or 19 percent – are of Maori descent, including 8 National MPs, 6 Labour, 3 Greens, 3 Maori Party, 1 NZ First, 1 Mana, and 1 Independent MP.

Saturday’s Ikaroa-Rawhiti by-election was run during the four-monthly Maori Electoral Option, which is held every five years following the Census to give Maori voters an opportunity to decide whether they want to be on the General Roll or the Maori Roll for the next two General Elections (new voters can enrol on the Maori roll or General roll at any time). The Option and the Census were due to be held in 2011 but were postponed following the Christchurch earthquakes.

This year’s Census was held on 5 March; the Maori Option opened on 25 March and will close on 24 July. The results will then used by the Government Statistician to calculate the number of Maori and General Electorates for the 2014 and 2017 General Elections. The results are expected to be announced in early October, and will then be used by the Representation Commission to determine the electorate boundaries for the next two elections. The proposed boundaries are expected to be released for public submissions in late November 2013, with the final determinations made in April 2014.

The first Maori Option, allowing Maori voters to switch rolls, was introduced in 1975, but the number of Maori seats remained fixed at 4. With the advent of MMP, the numbers of voters on the Maori Roll was used to determine the number of Maori seats and the result was an instant increase in the proportion of race-based seats in the New Zealand Parliament: under FPP there were 4 Maori seats out of 99 electorates, or 4.04 percent, whereas after MMP was introduced in 1996, there were 5 Maori seats out of 65 electorates, or 7.69 percent.

The 1997 Maori Option saw the number of voters on the Maori roll increase by 17,948 lifting the number of Maori seats to 6. In 2001 an additional 24,144 switched to the Maori roll, resulting in 7 Maori seats, and in 2006 14,914 switched to the Maori roll, but the number of Maori seats stayed at 7.

The large Maori Roll increases of previous years seem unlikely this time around - three quarters of the way through the present Maori Option, the total increase in the number on the Maori Roll is 5,198 and this is largely as a result of new enrolments. Some 7,727 voters of Maori descent, transferred from the General Roll to the Maori Roll, but this was effectively cancelled out by the 7,327 voters who transferred from the Maori Roll to the General Roll. Of the 6,842 new enrolments, 4,798 opted for the Maori Roll, while 2,044 opted for the General Roll.[2]

Graeme Edgeler, a Wellington barrister with a strong interest in electoral and constitutional law explains how the Maori Option works. He makes the point that because electorate calculations are based on the ordinarily-resident population rather than enrolled voters or the voting age population, data from both the census and enrolment forms is used to determine electoral populations:

“The Mâori electoral population is the group of people whose electorate representation in Parliament is through the Mâori seats. It is determined by taking the Mâori descent population (i.e. the number of ordinarily-resident New Zealanders who have a Mâori ancestor), and assigning a proportion of this group according to the proportion who are enrolled on the Mâori roll. So, if 60% of people who are listed on the electoral roll as being of Mâori descent are enrolled on the Mâori roll, then 60% of the overall Mâori descent population counts as the Mâori electoral population, and the other 40% are included in the general electoral population.

“But how do we know what the Mâori Descent population is? Well, question 14 in the Census asks: Are you descended from a Mâori (that is, did you have a Mâori birth parent, grandparent or great-grandparent, etc)? It is the answer to this question (and not the ethnicity question) that is used in determining the number of electorates of each type.

“For example, the calculation of the number of Mâori seats for the first MMP election was:

- On

their 1991 census forms, 511,278 people indicated they had

Mâori ancestry.

- After the 1994 Mâori Option, 51.7%

of people who indicated on their enrolment forms that

they

had Mâori ancestry were on the Mâori roll, so

the Mâori electoral population was 264,222

(which

is ~51.7% of 511,278).

- This Mâori electoral

population was enough people (not voters) for 5.11

Mâori seats, which got

rounded down to 5.”

Taking this explanation one step further, the Electoral

Act fixes the number of electorates in the South Island at

16, and the South Island quota - obtained by dividing the

South Island population by 16 – is used to determine the

number of North Island general electorates and Maori

electorates. Using the 1994 data, the South Island

population was 827,952, which when divided by 16, gives a

South Island quota of 51,747. If the Maori electoral

population is 264,222, then the number of Maori seats will

be 264,222 divided by 51,747, or 5.11, which is rounded down

to 5.

When researching this issue, it became very clear that a major change occurred in 1997, when the number of people classified as having Maori descent jumped significantly. It turns out that the Government Statistician unilaterally altered the way the Maori descent population was calculated by including in the total a proportion of those people who had not answered the Maori descent question in the Census clearly. Termed “imputation”, the process assesses responses that include “don’t know” or contain a confused answer, to increase the Maori descent population used in electoral calculations. As a result of imputation, the number of Maori seats in 2001 and in 2006, increased to 7 instead of staying at 6. This means that as a result of a largely unrecognised and unpublicised statistical manipulation, extra Maori seats have been in place since the 2002 general election.

As Graeme Edgeler explains, “The decision appears to have been made without fanfare, or public or political consultation… Nonetheless, I am a little disconcerted that a single person can make what is potentially a far-reaching decision with no real oversight, and almost in private. I wonder if what should happen in situations like this might be for the government body to seek a High Court declaration on what the law requires or allows. There will not always be a right answer, but there may be a wrong one.”

A further anomaly regarding Maori seats is a question relating to voter numbers. The Ikaroa-Rawhiti by-election results showed a voter turnout of only 35.8 percent of 33,937 enrolled voters. In comparison, voter turnout for the 2011 Botany by-election – a general seat - was 36.4 percent of 42,960 enrolled voters. So the question is, why do Maori electorates have fewer voters than general seats?

The answer is largely ‘demographic’. Because electorates are based on the ordinary resident population, then Maori electorates, with a younger population mix, will have fewer registered voters. In 2007, the North Island electorates had an average of 57,243 people, South Island electorates 57,562 people, and the Maori electorates 59,583 people, but with 45 percent of Maori under the age of 18, compared to 29 percent overall, a general electorate seat would have an average of 41,000 people of voting age, compared to around 33,000 in the Maori electorates.

All of this is information provides a backdrop to the bigger question that New Zealanders need to be asking – should the Maori seats be retained or abolished?

The future of the Maori seats is one of the key issues being addressed in the government’s constitutional review. Anyone who believes that race-based representation has no place in a modern society - that our democratic rights should be based on citizenship not race - needs to tell that to the Constitutional Advisory Panel, so they can include it in their report to the government. In politics, silence is taken as approval of the status quo. If you feel strongly that it is time to abolish the Maori seats - to make your opinion count, you will need to say so. The address to email your submission is constitutionalreview@justice.govt.nz.

THIS

WEEK’S POLL

ASKS:

Do you

believe the Maori seats should be retained or abolished?

Click HERE

to

vote

*Read this week's poll comments daily

HERE

*Last week only 3% of readers said they

would support a future government with Russell Norman as

Treasurer ... you can read the comments

HERE

FOOTNOTES:

1.

Philip Joseph, The

Maori Seats in Parliament

2. Electoral Commission,

Progressive

Results Maori Electoral Option

NZCPR Guest

Commentary: A LITTLE

KNOWN STORY OF THE MAORI

SEATS

By Graeme

Edgeler

“So what is the effect of the decision to impute Mâori descent to a proportion of those who don’t know, or wouldn’t say? It has increased the number of Mâori seats, and caused a slight decrease in the fair number of general seats in the North Island. As at the last boundary determination, it accounted for 0.8 of the 7 Mâori seats:

“Because of rounding, imputation hasn’t had a real effect on the number of North Island general seats (although it may be a matter of time), but as noted above, without it, 2001 would not have seen in an increase in the number of Mâori seats, and it would have stayed at six in 2006 as well.

“The decision of the Government Statistician – which in a close election could affect the balance of power – hasn’t had a lot of press, with the only public mention in the technical notes of the Government Statistician’s calculation.” ... read the full article HERE

ENDS

Gordon Campbell: Gordon Campbell On The Folly Of Making Apologies In A Social Vacuum.

Gordon Campbell: Gordon Campbell On The Folly Of Making Apologies In A Social Vacuum. Forest And Bird: Modernisation Of Conservation System Must Focus On Improving Conservation

Forest And Bird: Modernisation Of Conservation System Must Focus On Improving Conservation NZCTU: Uniformed Defence Force Should Not Be Used As Strike Breakers

NZCTU: Uniformed Defence Force Should Not Be Used As Strike Breakers MetService: Damp Start To Canterbury Anniversary Weekend; Wet Start For Coldplay Fans In Auckland

MetService: Damp Start To Canterbury Anniversary Weekend; Wet Start For Coldplay Fans In Auckland RNZ: Senior Lawyers Call For Treaty Principles Bill To Be Abandoned

RNZ: Senior Lawyers Call For Treaty Principles Bill To Be Abandoned Lobby for Good: Small Business Owners, MPs Rally Together To Demand Transparency In Tauranga Marine Precinct Sale

Lobby for Good: Small Business Owners, MPs Rally Together To Demand Transparency In Tauranga Marine Precinct Sale VisAble: National Apology Marks Important Step For Disabled Community, But True Change Requires Lasting Action

VisAble: National Apology Marks Important Step For Disabled Community, But True Change Requires Lasting Action