Professor Jane Kelsey: Big Brothers Behaving Badly

Page 1

Big Brothers

Behaving

Badly

The Implications for the Pacific Islands of the

Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER)

Professor Jane Kelsey

Commissioned by the Pacific Network on Globalisation

(PANG)

Interim Report

April

2004

Page 2

USP Library

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Kelsey, Jane

Page :

the implications for the Pacific Islands of the

Pacific

Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) / Jane

Kelsey. —

Suva, Fiji : Pacific Network on Globalisation,

2004.

p ; cm.

ISBN 982-9083-01-2

1. Pacific Agreement

on Closer Economic Relations 2. Oceania—

Foreign economic

relations—New Zealand 3. New Zealand—Foreign

economic

relations—Oceania 4. Oceania—Foreign economic

relations—

Australia 5.. Australia—Foreign economic

relations—Oceania 6. Commercial

treaties—Oceania I.

Pacific Network on Globalisation II.

Title.

HF1642.55.Z4N45 2004 337.95093

Big

Brothers

Behaving Badly

The Implications for

the Pacific Islands of the Pacific

Agreement on Closer

Economic Relations (PACER)

Professor Jane

Kelsey

Commissioned by the

Pacific Network on

Globalisation (PANG)

PO Box 15473

5 Bau

Street,

Suva

Fiji Islands

Phone: + (679) 3316

722

Fax: + (679) 3311 248

E-mail:

pang@connect.com.fj

Website: www.pang.org.fj

Page 3

Foreword

NGOs and church-based groups within the Pacific started to ask questions as soon as the Pacific Islands Forum announced in 1999 the creation of a free trade area for the Pacific. At that time (and in a sense still today) many of these civil society groups were struggling to comprehend the issues of free trade and globalisation, its technicalities and politics, and more importantly the various impacts on the communities, resources and small vulnerable economies of the Pacific.

The first glaring concern was the tremendous lack of public consultation and sharing of information on the negotiations by the Forum Secretariat and our own governments. They themselves said, at that time, that the creation of a free trade area was a defining moment in the history of the Pacific Islands Forum. Why, then, were Pacific peoples denied the opportunity to be active participants and contribute to this defining moment in the region’s history? What type of history was being created for us, and who was writing it, with what mandate?

Concerns about the lack of public information, and a desire to promote informed discussion and debate on the free trade issue, motivated NGOs such as the Pacific Concerns Resource Centre (PCRC), the Pacific Island Association of NGOs (PIANGO), The Development Alternatives for Women in a New Era (DAWN) - Pacific, and church based groups like the Ecumenical Centre for Research, Education and Advocacy (ECREA).

These groups were determined that the region’s civil society must not be caught napping and left without a voice, knowledge or awareness of these emerging issues.

A meeting of civil society groups from across the region on ‘Globalisation, Trade, Investment and Debt’ in 2001 saw the beginnings of the formation of Pacific Network on Globalisation (PANG). They highlighted the need to address the lack of research from the NGO community, including analysis, information, statistics and data, which could inform our responses, actions, and campaigns on economic and trade affairs that affect our people.

This report commissioned by PANG concentrates particularly on the politics and implications of the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER). The inclusion of Australia and New Zealand is where the Pacific free trade process was being pushed, right from the beginning. More follow-up studies are needed, especially on the impacts of PACER and its links to the Cotonou negotiations with the European Union, to give Pacific peoples more information on where we could be heading and a stronger basis from which we can be heard.

PANG would like to thank our partners Kairos-Canada and the World Council of Churches-Office of the Pacific for their support towards this project.

This study aims to not only increase the literature available on free trade issues in the Pacific, but also to provoke thought, discussion and debate, and encourage people to speak out and take action regarding the issues at stake. It also reiterates a call made by Pacific NGOs ever since the free trade area process began, that our governments heed the voices and concerns of their people before they decide to negotiate on any such agreement.

Stanley Simpson

Coordinator

Pacific Network on Globalisation (PANG)

Page 4

Preface

When the Forum Leaders mandated formal negotiations for a free trade agreement in 1999, they operated by consensus. But the expectations of the region’s two dominant players, Australia and New Zealand (NZ), and those of the Forum’s Island members were poles apart.

After two years of bruising negotiations, the proposed agreement among the Forum Island Countries was subordinated to a Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) to which Australia and NZ were full parties. This guarantees negotiations for a Forum-wide free trade arrangement if the Islands began similar negotiations with the European Union.

Australia and NZ are now insisting that PACER’s trigger has been pulled. They are meeting stubborn resistance that is, of necessity, couched in legal terms. But the real reasons are clear: the Forum Island governments resent the belligerent way that Australia and NZ forced PACER on them, and they increasingly understand that any agreement that includes Australia and NZ could devastate the Pacific Islands economies and the lives of their people.

This report analyses the political dynamics that led to PACER and will continue to underpin negotiations between the Forum Island Countries and Australia and NZ. It draws without attribution on forthright interviews with many people who were intimately involved in the PACER process. These are supplemented by a selection of documents, including from the historical files of the NZ Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Regrettably, the Forum Secretariat has not responded to repeated requests for copies of crucial papers and reports. I would like to thank all those who shared their insights with me and assisted in accessing documentation; they bear no responsibility for the interpretation I have placed on that information.

The picture that emerges is deeply disturbing. As one NZ government official confirmed with disarming frankness: when it comes to trade there is no ‘special relationship’ with the Pacific. Effectively, international trade strategy takes priority over the views of Pacific governments and the needs of Pacific peoples.

The report challenges the closed and pre-determined nature of a negotiating process that presents neoliberal globalisation as the only future for the peoples of the Pacific and that pre-empts the critical analysis and debate that should take place before such agreements are even contemplated. It explores the strategies that are currently being pursued by Australia and NZ, in competition and accord with the European Union, that treat the small and vulnerable Islands of the Pacific as pawns in their broader game plan - most recently through Australia’s proposal for a Pacific Economic Community.

The final section of the report canvasses a range of legal and political exit routes that are available to the Forum Island governments, including withdrawal from and termination of PACER itself. It argues that governments will be in the strongest position ttake these steps if they are backed by parliamentary mandates based on informed and participatory public debate, and draws upon the Biketawa Declaration to suggest ways in which this might be done. Opposition is not enough. There is an urgent need for debates nationally and regionally on alternative development strategies and forms of regional cooperation.

Australia and NZ need to play a truly supportive, secondary role in this process.

These proposals call for leadership from the governments of the region and a willingness to embrace a new level of openness and accountability when negotiating international treaties. They also offer new opportunities for non-government organisations, social movements, trade unions, churches, academics, local businesses and the media of all Forum countries to engage in debates that are crucial to the future.

This is an interim report of a technical nature that is timed to coincide with the April 2004 meetings of the Pacific ACP and Forum Ministers at which such issues will be discussed. A final report that is addressed more to the region’s NGOs, social movements, churches and unions will be released in June at the time of the Forum Economic Ministers Meeting in Rotorua.

I hope that both reports will provide a catalyst for the kind of analysis and debate that should have occurred at the time PACER was first proposed.

Dr Jane Kelsey

April 2004

Page 5

Table of Contents

Foreword 3

Preface 4

Abbreviations 6

Overview 7

From

Old Colonies … To New Empires 9

The Negotiating

Environment 11

The Origins of PICTA and PACER 13

What

Motivated Australia and NZ? 14

What Motivated the

FICS? 15

Backroom Bullies 16

Turning the Tables on the

FICS 17

The PACER ‘Triggers’ 19

PACER’S

Principles 20

Self-fulfilling Consultancies 21

The

Scollay Report 22

The Stoeckel Report 23

A Social

Impact By-Pass 24

Real World Risks 25

Surrendering

Services 26

A Bill of Rights for Foreign

Investors 27

A Helping Hand 28

Thought

Control 29

Un-Common Interests 30

Stepping Stones to

Where? 31

PIC Pawns in a Power Play 32

Disarming the

Trigger 34

Capturing the Secretariat 37

Recolonising

the Pond 38

Revisiting ‘Good Governance’ 39

Positive

Climate Change 40

Recommendations 41

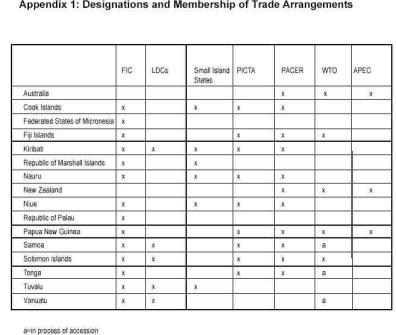

Appendix 1:

Country designations and trade affiliations 42

Appendix

2: People Interviewed 43

Appendix 3: References 44

Page 6

Abbreviations

ACP African, Caribbean and

Pacific Countries

ADB Asian Development Bank

AITIC

Agency for International Trade Information and

Cooperation

APEC Asia Pacific Economic

Cooperation

AUSAID Australian Agency for International

Development

CER Australia New Zealand Closer Economic

Relations Trade Agreement

DDA Doha ‘Development’

Agenda

EBA Everything But Arms

EU European

Union

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FEMM Forum

Economic Ministers Meeting

FICs Forum Island

Countries

FTA Free Trade Agreement

FTMM Forum Trade

Ministers Meeting

GATS (WTO) General Agreement on Trade

in Services

GATT (WTO) General Agreement on Tariffs and

Trade

GSP General System of Preferences

IMF

International Monetary Fund

IPPA Investment Promotion and

Protection Agreement

LDCs Least Developed

Countries

MAI Multilateral Agreement on Investment

MFN

Most Favoured Nation status

MSG Melanesian Spearhead

Group

NAFTA North American Free Trade Agreement

NGO

Non-Government Organisation

NZ New Zealand

NZAID New

Zealand Agency for International Development

OECD

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and

Development

PACER Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic

Relations

PACP Pacific members of the ACP

PICs Pacific

Island Countries

PICTA Pacific Island Countries Trade

Agreement

PNG Papua New Guinea

REPA Regional Economic

Partnership Agreement

RTFP Regional Trade Facilitation

Programme

ROOs Rules of Origin

SPARTECA South Pacific

Regional Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement

SPS

Sanitary and Phytosanitary

SVE Small Vulnerable

Economies

TCF Textile, Clothing and Footwear

TEAG

Trade Experts Advisory Group

US United States of

America

USP University of the South Pacific

VAT Value

added tax

WTO World Trade Organisation

Page 7

Overview

For more than 20 years, Pacific Island countries have come to depend on preferential trade arrangements such as SPARTECA with Australia and NZ and the Lomé Agreement with the European Union (EU). That era is now past. A sea of acronyms - WTO, APEC, FTAs, IPPAs, PICTA, PACER, the Pacific REPA – signifies an interlocking network of agreements that aim to lock all the countries of the world into a straitjacket of neoliberal policies and global markets, irrespective of their wealth, size or vulnerability. Old colonial powers, freed from their responsibilities for poor and vulnerable former colonies, are flexing their muscles and building new empires that serve their current economic, strategic and political interests. Publicly, the Pacific Island governments have been convinced by Australia and NZ to embrace this brave new world. Behind the scenes, they seem increasingly hesitant. Today, the globalisation juggernaut has stalled in the face of challenges from Southern governments and social movements and there is political space to think again.

In 1997, when the Forum Island governments endorsed the idea of a free trade area, they opened a Pandora’s box. They were originally convinced to support a two-stage process, beginning among themselves and extending to Australia and NZ over a 20 year period. When told that the World Trade Organisation (WTO) would only allow 10 years if Australia and NZ were involved, they retreated into a limited arrangement among themselves that they optimistically believed they could manage.

But Australia and NZ were not about to be excluded from a major economic initiative in ‘their lake’. Nor would they stand by as the European Union (EU) renegotiated its relationship with the Pacific Islands and secured superior free trade commitments through the Cotonou Agreement.

There was no public debate about whether this was the best way forward for the Pacific or whether the costs might outweigh any gains. Negotiations were conducted behind closed doors. The treaty text underwent at least four major reformulations before Australia and NZ were prepared to let it be signed. Accounts of these meetings reveal a pattern of arrogance and intimidation that was led by Australia and condoned, and sometimes mirrored by, NZ. The result was an ‘umbrella’ Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) that promised Australia and NZ negotiations on a free trade arrangement and economic integration with a view to forming a single regional market. These would begin in 8 years time (2011), unless triggered earlier by negotiations with other countries (viz. the EU). Under PACER sat a Pacific Island Countries Trade Agreement (PICTA) that provided for free trade in goods among Forum Island Countries within 8 years (2010) for all ‘developing members’ and 10 years (2012) for the Small Island States and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) [Appendix 1]. This was a victory and a defeat for the Island governments. They had bought time, with a promise to Australia and NZ that might never produce an actual agreement. In political terms, however, Australia and NZ had secured enough leverage to require a further round of negotiations. That has left a deep sense of resentment. Now, less than two years later, Australia and NZ are insisting that these negotiations begin.

The consultants’ reports commissioned by the Forum Secretariat to support the process were largely window dressing. Their narrow philosophy, tools and terms of reference made their findings a foregone conclusion. Keeping them confidential effectively closed down debate and allowed the fallacy that small and vulnerable islands can compete in a deregulated global economy to go unchallenged. Genuine consultation was limited to selected members of the private sector. Calls from nongovernment organisations for a qualitative and participatory study of the implications for Pacific peoples, their communities, the environment, culture and democracy were ignored. Instead a superficial, largely quantitative study was presented to ministers at the meeting where the agreements were signed. Hard questions about impact of inevitable business closures, loss of jobs and revenue shortfalls on the economic, social and political stability of the Islands were never properly engaged – let alone the consequences of extending such commitments to Australia, NZ and the EU.

PACER came into effect before PICTA, partly because it needed fewer Pacific Island parties and because it obliged Australia and NZ to fund trade facilitation and financial and technical assistance to the Forum Island Countries. Technically, the Regional Trade Facilitation Programme is to be agreed by consensus. But Australia and NZ hold the purse strings. Their decision to fund only half of what was asked for is viewed by some as realistic and by others as proof of how they manipulate the rules to suit themselves. Financial and technical assistance are channelled mainly through the WTO, whose programmes have been strongly criticised for promoting the positions and interests of the major powers. PACER also mandates mutual assistance in matters where the parties have common interests, especially the WTO. Yet Australia and NZ and the existing WTO members (Fiji, Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Solomon Islands) are on opposite sides on most issues. The hardline approach of Australia and NZ to the WTO accession negotiations of Samoa, Vanuatu and Tonga has fuelled the sense of anger and outrage.

Page 8

From Old Colonies...To New Empires

PICTA provided for gradual liberalisation of trade in goods over a 10-year period. Implementation has been slow and reflects similar experiences with the Melanesian Spearhead Group. Belatedly, questions are being raised about the cost of ‘adjustment’.

Faced with the prospect of more complex and far-reaching agreements with Australia and NZ, and the EU, Pacific Island governments have begun developing strategies to defer the negotiations and minimise the scope and scale of any commitments. But, even if they avoid the triggers, PACER will require negotiations in 2011. Sooner or later, the Pacific Islands governments will face a re-run of the PICTA/PACER scenario. Their officials admit that they do not have the capacity to analyse the likely implications and face cultural barriers in standing up to Australian-style bullying. There is a serious danger that ministers and officials will be tempted to continue playing a game they cannot possibly win because they do not believe they can say ‘no’, especially if that threatens future access to aid funding. Yet withdrawal from and termination of PACER is the only way they can avoid becoming trapped in a web of enforceable obligations they cannot afford to implement.

Already the Forum Island governments are being urged to lock in further ‘stepping stones’. PICTA originally deferred the complex and controversial question of ‘trade in services’. Now, it seems, governments are being asked, on the basis of confidential consultancy reports, to make binding commitments within a year. Services agreements intrude deep into the traditional spheres of government policymaking and affect people’s access to essential social and public services; yet the Forum Secretariat does not plan to conduct any studies into the implications. The same is happening with the even more controversial proposal for rules to protect foreign investors – despite opposition from Fiji, Solomon Islands and PNG to similar negotiations on investment rules at the recent WTO ministerial meeting in Cancun.

This is not just a power grab by Australia and NZ for control of the South Pacific. As a World Bank report spelt out in 2002, PACER aims to lock the Pacific Islands irrevocably into the neoliberal paradigm. The link to the Pacific Regional Economic Partnership (REPA) negotiations with the EU is partly defensive. But PACER and Cotonou are also flip sides of the same coin. Both swap preferential agreements for reciprocal ones that guarantee more extensive market access without having to make any additional concessions. Both promise sensitivity to the realities of poor, small and vulnerable Pacific Islands, while they treat them as pawns to advance their global strategic game plan. Both reach beyond the rapidly expanding ‘trade’ agenda of goods, services, investment, competition and procurement to advance the Washington Consensus policies of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, including labour market ‘flexibility’, fiscal austerity and privatisation of state assets and services. The broader and deeper the liberalisation, the more ‘structural adjustment’ will be required.

The current review of the Forum Secretariat, with its anticipated proposal for a Pacific Plan, could provide the Trojan horse that propels this agenda into the heart of the Pacific. Australia’s vision, articulated in a series of recent reports, talks of a common currency, free movement of people, shared labour laws, harmonised tax regimes, common standards and qualifications, pooled services and a commitment to ‘sound’ (neoliberal) economic policies, including private property rights, an independent central bank and fiscal discipline. The implications for the region would be profound. There is a sense of déjà vu – that Australia and NZ could manipulate a seemingly benign commitment to a vaguely worded vision to impose their ideology, their neoliberal policies, their free trade agenda, their institutions and operatives, their economic interests, their political authority and their strategic influence on the Islands of the Pacific. The proposed free trade arrangement, embedded in the broader project of regional economic integration and run through a streamlined Secretariat with a strong executive, is critical to achieving that goal.

Pacific governments have so far excluded their people from debating these developments through the secretive and antidemocratic way that trade negotiations are conducted. It seems perverse that the “Biketawa” Declaration commits the region’s governments to principles of accountable, participatory, democratic government - yet these are not applied to trade negotiations whose impact on people’s lives will be more far-reaching than almost any decision taken by a national government and which tie the hands of governments for decades to come.

The people – NGOs, social movements, trade unions, local businesses and the media - are powerful potential allies of Pacific Island governments in rejecting the neoliberal agenda and developing their own Pacific Plan to address the urgent and serious challenges that are facing them. In the true spirit of the “Biketawa” Declaration, it is time for Australia and NZ to recognise that they risk creating a powder keg that will intensify the instability and threats to security in the Pacific, and to abandon their recolonisation agenda. Equally, it is time for the governments of all Forum countries to entrust their people with the right to determine their own future through open and participatory dialogue about the kind of development and regional cooperation they believe is good for them.

Page 9

In 1973, when the South Pacific Forum was established with a mandate that foresaw ‘the possibility of establishing a free trade area for the South Pacific Region’, the world looked very different from now. Pacific Island countries were in the process of securing their political independence from Australia, New Zealand, Britain and France. The colonial powers acknowledged they had ongoing obligations, as the UN decolonisation programme required. Development theories placed the onus on wealthier countries to support poorer ones, consistent with the Keynesian-style interventionist economics and redistributive welfare state policies that prevailed at the time.

This was accompanied by paternalist rhetoric. Australia and NZ remained unrepentant for their brutal suppression of indigenous independence movements in the Pacific. They rationalised such behaviour as enhancing the welfare of the Islands and the human development of their people – just as they justified similar behaviour towards indigenous peoples in their own countries.

Colonialism created a structural inter-dependency. The colonial powers had profited from exploitation of the resources and labour of their former colonies, and were concerned to protect their residual economic interests. Colonial plantations in Fiji and Samoa had provided super-profits for Australian, British and NZ companies. By literally stripping the landscape of Nauru, Australia and NZ fertilised the pastures that made their own agriculture so profitable. While Australian interests mined PNG and Bougainville, French companies extracted New Caledonia’s nickel deposits. Transport, communications and financial infrastructure were designed to serve these interests. NZ and Australia imported cheap unskilled migrants from the Pacific to fuel their economic boom, only to exclude or unceremoniously deport them when economic fortunes declined and local unemployment grew.

The Pacific Islands became politically independent nations, but they inherited institutions of government and law that had been designed to serve colonial economic and political interests. Most were rudimentary and based on patronage. Public access to basic utilities was poor, as were opportunities for paid employment. Wageworkers had few protections and attempts to organise, especially among imported labour, had not been encouraged and were periodically suppressed.

The newly independent Island states were economically unsustainable without external support. Almost all viable enterprises were foreign owned. They had no significant indigenous economic, commercial or industrial infrastructure or domestic capital. The state was the only viable source of new economic activity and hence the primary employer. To earn foreign exchange and achieve a modicum of self-sufficiency they needed preferential access for exports to their traditional markets.

Tariffs on imports were the primary source of government revenue and, coupled with aid funding, were essential to maintain public services, utilities and employment.

Cold War concerns with regional stability and security gave the Pacific Islands leverage in securing preferential arrangements from Australia, NZ and Europe. From 1981 Australia and NZ guaranteed non-reciprocal access for scheduled exports from 13 Pacific Island countries under the South Pacific Regional Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement (SPARTECA).

This was critical to the birth of the textile and garment industry in Fiji and survival of small export sectors in many of the Islands. A comparable arrangement known as the Lomé Agreement was developed between European powers and their former African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) colonies. After Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973, Lomé was gradually extended to the Pacific Islands for whom protocols for bananas and sugar, and duty free entry for canned tuna, provided vital economic lifelines.

From the mid-1980s, these arrangements came under attack. Old ideas were no longer fashionable. Neoliberalism displaced Keynesian interventionism as the prevailing ideology of the ‘developed’ world. Once the Cold War ended in the early 1990s there was no ideological contest and no need to keep the poorer countries onside. Globalisation was portrayed as inevitable, irresistible and irreversible. Competitive self-interest replaced notions of colonial obligation. Development theorists abandoned their support for self-sufficiency and argued that poorer countries must integrate into the global economy.

A cookie cutter approach to policy emerged. It was named the ‘Washington Consensus’ after the nerve centre of the IMF, World Bank and United States (US) government. The aim was to create conditions where capital could maximise its profits and face the fewest possible barriers at home and internationally. That extended across fiscal, monetary, trade, privatisation,

Page 10

property rights, tax redistribution, free trade and investment policies. This latest vogue in economic policies was portrayed as unquestionable, scientific and ‘sound’. Any other policy agenda was intrinsically ‘unsound’. Implementing ‘sound’ policies became the standard conditionality for debt financing to poor countries. Voluntary ‘structural adjustment’ allowed richer countries more flexibility to meet their domestic economic and political imperatives and take a more pragmatic approach, although some (notably NZ) chose not to do so.

The same policy template was applied across ‘developed’, ‘developing’ and ‘least developed’ countries. It was no longer acceptable to argue that small, poor and vulnerable nations were structurally disadvantaged and required fundamentally special and differential treatment. They just needed more time to adjust to the new ‘unalterable’ realities. Multilateralism and reciprocity were the new panacea. Preferential trade agreements like SPARTECA and Lomé came under attack, as governments and exporters from other countries complained that they breached the ‘most favoured nation’ (MFN) pillar of the multilateral trading system that requires exports from all foreign countries to be treated equally. Transnational corporations orchestrated complaints that preferential agreements discriminated against the poor countries in which they happened to operate.

These increasingly powerful transnational companies and their parent governments in North America, Europe and Asia demanded new agreements to promote and protect their interests. They argued that the free trade rules on goods under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) should apply to a wide range of other international transactions. The most obvious was the rapidly growing and lucrative sphere of services, such as finance, tourism, transport, retail, entertainment and telecommunications. They also wanted to safeguard their monopolies over new technologies and innovations by requiring all countries to adopt US-style intellectual property laws. They pushed, less successfully, for multilateral rules to protect the profitability of their investments. The same governments promised to change their protectionist practices in agriculture and textiles; but the new rules allowed these practices to continue.

Overseeing the new agreements was a supra-national institution, the World Trade Organisation. It was supposedly run by a consensus of all its member countries, small and large, rich and poor. But the WTO elevated power politics to a new plane.

The WTO was mandated to work with the IMF and World Bank to promote a coherent model of ‘global economic policy making’, based on a common ‘sound’ neoliberal agenda. This reached beyond strictly economic policies into social policy and the essence of government.

Simplistic generalisations accused the governments of poorer countries of corruption, bad management and/or aid dependency and blamed them for the continued poverty of their people. The solution – ‘good governance’ - was itself deeply undemocratic and often enforced through debt conditionalities, tied aid and multilateral regimes. Governments were encouraged to limit the role of the state and rely on the deregulated market to deliver economic and social welfare to their people, transfer the country’s infrastructure to foreign investors, and bind themselves and future governments to the current fashion of neoliberal policies. Paradoxically, this created new opportunities for corruption. Binding and enforceable international trade and investment agreements were especially powerful in limiting the policy space and autonomy available to governments - and in denying their citizens the right to decide what development means and the policies by which it might best be achieved.

Australia and NZ were leaders in this transition. From 1984 NZ’s radical neoliberal programme was hailed internationally as an example to the rest of the world. Australia’s initially more pragmatic approach caused less drastic damage to its economy and social fabric. Both countries were free trade evangelists. They signed a groundbreaking free trade agreement covering goods in 1983 and extended it to services in 1989. Australia drove the creation of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in 1989 as a catalyst for regional free trade and investment, because the Uruguay Round of the GATT was faltering and the North Americans and Europeans were deepening their regional economic integration through the Canada- US Free Trade Agreement (later North America Free Trade Agreement or NAFTA) and the EU. Both countries eagerly embraced Asia as the key to the future, until the financial crisis of the late 1990s.

The Pacific was viewed as an inherited millstone - but one they were determined to keep under their control. As the multilateral regimes began to falter and a scramble for regional and bilateral deals accompanied the revival of US imperialism, Australia and NZ focused on securing their own small sphere of influence. The desire to recolonise ‘their lake’ now dominates their economic, political and military relationship with their Pacific neighbours.

Page 11

The Negotiating Environment

A number of specific developments shaped the context in which PICTA and PACER were negotiated. They continue to affect Australia and NZ, and the Pacific Islands, collectively and individually, in different ways.

The WTO is in crisis. Tensions have divided the WTO since its first ministerial meeting in Singapore in 1996. Poorer countries wanted to revisit elements of the Uruguay Round agreements that they could not implement for technical, economic and political reasons. They also demanded proper protection for Small Island States, genuinely special and differential treatment for LDCs, and accelerated access for agriculture and textiles into protected rich country markets. Wealthy countries, led by the EU, wanted the WTO to expand into new areas that became known as the Singapore Issues: investment, competition, government procurement and trade facilitation, and to import labour and environmental standards into core agreements. At the third ministerial meeting in Seattle in 1999 these internal divisions, coupled with street protests, paralysed moves to mandate a new ‘millennium’ round of trade negotiations. Tenuous consent to the new round was secured in Doha in 2001, in the intimidating shadow of September 11. The terms and conduct of those negotiations further inflamed North-South tensions and opposition from social movements, and culminated in the collapse of the most recent ministerial meeting in Cancun in 2003. The solidarity and resolve of the ACP countries, including Fiji, PNG and the Solomon Islands, played a pivotal role in the ability of Southern governments to hold the line.

These dynamics infect all contemporary trade negotiations. Australia and NZ are aggressive demandeurs at the WTO, where they spearhead the Cairns Group of agricultural exporting countries. Their quest for ever-stronger commitments and ‘high quality’ precedents drives their global trade strategy, including in the Pacific. The Pacific WTO members are on the other side in the Doha Round. Countries that are currently in the process of accession - Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa - have faced aggressive demands from Australia and NZ to make commitments beyond those required of existing WTO members. Non- WTO members are affected too, as any resulting free trade agreements are required to be compatible with GATT Article XXIV.

The Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum has also run out of steam. The ‘Bogor’ commitment to free and open trade and investment by 2010 for the richer members of APEC and 2020 for the poorer ones is voluntary and non-binding. It is unlikely to be implemented by the vast majority of APEC members. That has not stopped Australia and NZ from invoking the 2010 date to justify their demands for regional free trade and unilateral liberalisation to eliminate tariffs. With PNG as a member ‘economy’ and the Forum Secretariat having observer status, Australia and NZ will continue to use APEC to justify radical demands and timelines.

NZ and later Australia have turned towards bilateral free trade and investment negotiations. Under NZ’s original strategy, governments who champion free trade would negotiate deals with each other to create a regional patchwork that could revitalise the multilateral system (Groser, 2000). Tangible economic benefits - or costs - were a peripheral concern. More recently the breakdown of multilateralism and the revival of US imperialism has made the marriage of foreign affairs and trade more explicit, as exemplified by the Australia/US free trade negotiations. Given this combination, it is inconceivable that Australia and NZ would accept being excluded from part of the patchwork in their back yard.

Trade liberalisation by Australia and NZ has eroded the trade preferences under SPARTECA. Australia and/or NZ are significant export markets for the Forum Island Countries (FICs), except the Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands and Palau that have Compacts of Free Association with the US. Trade preferences under SPARTECA provided vital lifelines;

radical trade liberalisation by Australia and NZ is making them valueless. The most significant exception is the retention of tariffs for textiles, clothing and footwear (TCF). Fiji’s short-term concessionary arrangement for TCF with Australia is due to expire in December 2004 and its continuation has been opposed by the Australian unions and affected communities.

The EU aims to replace Pacific Islands’ preferential access with reciprocal free trade obligations. A successful US-led complaint to the WTO against preferential market access for ACP bananas in 1997 had implications for other commodity-specific agreements. The EU used the WTO case to support its plans to replace trade preferences under Lomé with reciprocal Economic Partnership Agreements on a regional level. The negotiating framework was established in the Cotonou Agreement between the EU and the ACP countries in June 2000. Phase I began in September 2002 and was supposed to settle

Page 12

broad issues across the entire ACP group. The ACP argue that these core principles must be finalised before regional negotiations begin, but the EU has insisted that they run in parallel with Phase II negotiations at the regional level. In a classic display of divide and rule, four of the seven regional negotiations have now begun. Negotiations for a Pacific REPA are scheduled to start in mid-2004 - hence the importance to the EU of the PICTA process, which it is rumoured to have partly bankrolled. In what has become a competitive market for trade negotiations, Australia and NZ will be determined to ensure parity, if not supremacy, in their negotiations with the Pacific Islands.

The Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) trade agreement is symbolically important, but in trouble. The MSG was formed by PNG, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in 1993 and focused on a small number of key products in which each country had a comparative advantage. Fiji joined in 1998. The Melanesian governments, especially PNG, have promoted the MSG as the appropriate vehicle for a smaller-scale, gradual and Island-only approach to free trade and the basis for any broader agreement with Australia and NZ. By 2000 the MSG had begun to fracture. Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands have effectively suspended their commitments, citing revenue crises. Exporters have also complained that it has not produced the benefits they expected. The failure of the MSG is blamed by some on the rush to sign an agreement when countries were in no position to comply and by others on instability and the lack of government resolve to address their domestic economic problems.

Donors require trade liberalisation. The East Asian crisis had a serious impact on exchange rates and the competitiveness of Pacific exports, yet the Asian Development Bank (ADB) diverted funding from the Pacific’s concessionary financing facility to prop up the Asian economies. By 2000 the ADB had adopted a ‘new’ sub-regional development strategy that purported to strengthen Pacific Islands ownership of policy and reform programmes and take better account of local culture and capacities.

This is old wine in new bottles. The augmented Washington Consensus policies have a strong focus on trade liberalisation;

acceding to the WTO was one condition for Vanuatu’s bailout from the ADB in 1998. Such conditionality provides a means of locking the Pacific Islands into the global economy and forcing consequential restructuring onto their economies. It is supplemented by a contradictory notion of ‘good governance’ that constrains governments’ ability to respond to democratically generated demands. The worthy ‘Millennium Development Goals’ agreed at the UN in September 2000 – to halve the number of people in poverty and without access to safe water, universal primary education, and more – are framed within market models and private sector delivery of public services. This is reinforced by IMF conditionalities that require governments to shift from tariffs to consumption tax, cut spending and privatise. Bilateral aid has also fallen in real per capita terms and is targeted much more tightly. In line with the international trend, the governments of Australia and NZ increasingly tie their aid to ‘good governance’ and technical assistance to institute ‘sound’ (neoliberal) policies. (GAO, 2001; Teaiwa et al, 2002; AFDAT, 2003).

Relations between Australia and NZ and the Forum Island Countries are strained. Commentators have noted a new intimacy between Australia and NZ as they present a common front in the Pacific on structural adjustment, globalisation and security:

‘Australia is often said to be the superpower of the South Pacific. If so, then New Zealand is certainly the second, with Wellington playing London to Canberra’s Washington.’ (The Australian, 25 August 2003) Maintaining this regional role is vital to the NZ government, as Canberra policy-makers no longer engage them seriously on larger foreign policy matters. Their shared criticism of post-coup Fiji and corruption scandals in Vanuatu and PNG, and support for the pro-democracy movement in Tonga, were seen as unwelcome interference from former colonial powers. While their belated support for the independence of East Timor and interventions in the Solomon Islands, and NZ’s constructive role in Bougainville, have been cautiously welcomed, they also deepened suspicions of a strategy to recolonise the region. This has been heightened by Australia’s deployment of personnel to police both law and order and the economy of PNG, and its demands for immunity.

The power imbalance in favour of Australia and NZ as aid donors, regional police and funders has created a ‘them’ and ‘us’ division within the Pacific Islands Forum. Tensions increased after Australia refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, despite pleas from Islands that are threatened by global warning, and Prime Minister Howard missed several of the Forum Leaders meetings.

When Ratu Sir Kamasese Mara warned the Forum Leader’s in 2001 that Pacific Island countries need to be vigilant and ensure they are fully in control of their destiny because ‘too often aid comes with strings attached’, NZ Prime Minister Helen Clark described Mara’s comments as ‘unfortunate’ (OneNews,17 August 2001). This was the meeting at which PICTA and PACER were signed.

Page 13

The Origins of PICTA and PACER

The Forum Secretariat was mandated to investigate the development of free trade among Forum Island Countries (FICs)

when it was established in 1991. The proposal for a Pacific Regional Trade Agreement was tabled and endorsed at the Forum Economic Ministers Meeting (FEMM) in July 1997. They instructed the Secretariat to report to the next year’s meeting with options and a framework that gave ‘due regard to benefits from preferential and non-preferential approaches, taking into account the need for WTO consistency, and differing speeds at which FICs could do so.’ After considerable debate, two reports were commissioned. One looked at the potential economic benefits and costs of a free trade agreement in goods and services amongst the FICs; it reported the economic gains would be minimal, but there were non-economic benefits (Scollay, 1998). The second used the same methodology to examine the benefits and costs of including Australia and NZ, which they funded; it projected substantial welfare gains to the FICs and relatively limited benefits to Australia and NZ (Stoeckel, 1998).

These reports (and a third applying the same computerised modelling to liberalisation on a non-preferential (MFN) basis (Scollay and Gilbert, 1998)) were presented to the FEMM in June 1998. Following a slick power-point presentation of the Stoeckel report and analogies with the Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement between Australia and NZ (CER), the meeting recommended that the Leaders should endorse, in principle, a free trade agreement that included all Forum members, and convene a meeting of Forum Trade Ministers in 1999. They also instructed the Secretariat to develop a framework for an agreement. The idea was for a ‘10+10’ approach, giving the FICs a decade to phase in free trade among themselves and another decade to phase in commitments to Australia and NZ. But lawyers warned that this would exceed the time frame of 10 years allowed for regional trade agreements involving OECD countries under GATT Article XXIV. That would be simply unmanageable. The draft legal text they prepared for the Secretariat and distributed to members attempted a compromise: a FIC-only agreement, with the option of a protocol that included Australia and NZ.

The Forum Trade Ministers Meeting (FTMM) in June 1999 recommended that the Leaders should instruct the Forum’s trade officials to negotiate the details ‘and measures to provide for application of the agreement to Australia and New Zealand in appropriate ways.’ They wanted the final agreement ready for consideration by Ministers and endorsement by Leaders at their 2000 Forum meetings. The Ministers also approved studies on

- the effects of extending a free trade area to the Compact States and French Territories;

- the effects of extending the free trade agreement to services;

- the longer term integration of a free trade agreement into CER;

- market access issues with the US and Japan;

- a social impact study; and

- a paper on trade facilitation.

The wording adopted at the Leaders Meeting in October 1999 instructed officials to consider ‘measures to provide for the application of the arrangements to Australia and NZ’. The FICs later insisted that, even though the Leaders had dropped the phrase ‘in appropriate ways’ this did not require Australia and NZ to be included and certainly not as full parties. Australia and NZ appealed to the spirit of the instructions and the unity of the Forum to support demands for full ‘parties principal’ status in any regional free trade arrangement.

The Forum Secretariat was responsible for implementing these instructions and played a crucial role in interpreting the mandate. In his Opening Statement to the pre-negotiations workshop in March 2000, Secretary General Noel Levi said the Secretariat’s role was merely to facilitate the task of finding appropriate ways to apply the FIC-only agreement to Australia and NZ. But members needed to take ‘certain expectations contained in the Leaders decision’ on board. In particular, the measures they produced had to be ‘appropriate’ in terms of the original intention and objectives of the free trade area: ‘to be an enabling mechanism for the developing country members of the Forum…. The challenge is for all of us to focus on that challenge and not to be sidetracked by issues that are not pertinent to the task.’ The Forum Island governments had created a rod for their own backs by conducting these discussions in secret. Had they opened the idea of a free trade agreement to public debate back in 1997 and released the background documents to allow independent and critical scrutiny, they may have been convinced not to proceed. They would certainly have had more basis for rejecting Australia and NZ’s demands. Instead, by opting to create a seemingly limited free trade agreement among themselves they opened a Pandora’s box that they could not control.

Page 14

What Motivated Australia and NZ?

Publicly, Australia and NZ approached these negotiations in the spirit of benevolence and regional solidarity. Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer told the Australia Fiji Business Council in December 1999:

It is better to take steps towards becoming globally competitive by firstly competing with Australian and New Zealand goods and services, where island countries will be operating in a sympathetic environment, with countries that understand the island countries’ needs and requirements and are strongly committed to their development.

But their intentions were far from benign. As Forum members, benefactors of SPARTECA and major aid donors, Australia and NZ were not about to be excluded from a free trade area in their back yard. As then Associate Foreign Affairs Minister Matt Robson observed in response to the 2001 review of NZ’s aid agency, NZ had a policy ‘of ensuring that our political needs are met first and foremost before the development needs of other countries’.

New Zealand initially seemed relaxed about the proposal, and was prepared to let the FICs work it out among themselves, provided it did not interfere with the wider structural adjustment programme. Australian officials were much more aggressive.

Once the first formal text appeared, NZ’s attitude hardened and the two governments began a close collaboration to ensure their inclusion or, failing that, to ensure the project did not proceed. Downer reportedly issued instructions that nothing was to be called ‘Pacific Regional’ unless Australia was involved, and a free trade agreement to which Australia was not a full party was simply not an option. On numerous occasions they ridiculed the idea that a FIC-only agreement could get off the ground without them. Samoa is said to have complained formally about Australia’s behaviour.

Initially, they were motivated by pique that the Island countries had dared to exclude them. Australia and NZ view the South Pacific as ‘their pond’, although it is impolitic to say so publicly. As founding members of the Forum (a status that still rankles with some) they were not prepared to accept their exclusion from its most significant economic initiative. Only full party status would allow them to influence the future direction of the agreement, such as the extension beyond goods into services, and the admission of new members. Their determination intensified as negotiations on the Cotonou Agreement sharpened in late 1999. According to NZ’s trade files, full participation was considered necessary to prevent the EU from stealing a march on Australia and NZ in the Pacific and to ensure that both countries had a role in future negotiations between the Pacific Islands and the EU so they could pursue their trading interests.

These two principal motives were confirmed in the evidence from Australian officials on 13 May 2002 to the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties that examined the implications of PACER for Australia:

The first [objective] was political. We did not want the island countries, using the forum label, developing a free trade agreement between themselves which ignored Australia and New Zealand. For reasons of state we thought, “We’re members of the forum; we deserve to be included in some way”. Secondly, a practical or economic interest of ours was to ensure that, whatever trade liberalisation occurred between the island countries, if it were extended to other states such as the United States, Japan or the EU, it did not disadvantage our trading position.

Australia and NZ’s preoccupation with status and patch protection dominated the PICTA/PACER negotiations. At a more general level, both governments also saw free trade agreements as a means to extend and lock in neoliberal policies and commitments to globalisation by Island governments that had a mixed record on sustained restructuring. There was no question that benefits would flow.

The trade impacts of a free trade agreement itself were a marginal consideration. The Stoeckel report, which Australia and NZ had commissioned from the neoliberal Centre for International Economics to support their participation, was more a propaganda tool than a serious economic assessment (Stoeckel, 1998). The methodology guaranteed projections of much larger welfare benefits to the FICs if Australia and NZ were included, but gains to Australia and NZ were considered relatively insignificant. This was echoed in NZ government papers. Both countries had massive trade imbalances with the Pacific and the impact of removing tariffs on their exports was considered minimal. The far greater concern was the risk that tariff free competition for goods from the EU, promises of open market access and non-discrimination for European services providers, and guaranteed protections for European investors could seriously disadvantage Australian and NZ companies that lacked the same guarantees.

Page 15

What Motivated the FICS?

Why would Pacific Island governments go down this path? Secretary General Noel Levi gave five reasons in a Question and Answer document prepared for the Forum Trade Ministers Meeting in 1999 (Levi, 1999).

1. The economic rationale saw a market of 6 million people as allowing the benefits of scale to countries with limited domestic markets and the ability to increase their production. While most of the Islands produce very little to trade with other countries, and much of that production is similar, no one could foresee the future. If Australia and NZ had benefited from an expanded market, so could the Pacific. However, Levi’s optimism ignored the counter-factuals. The potential for the Island countries to expand their exports was constrained by poor technology, skills and infrastructure and vulnerability to natural disasters.

Transport costs are significant. It was very likely that a ‘hub and spoke’ effect would attract investors from outside and within the region to one country, Fiji, from where they could export duty free across the Pacific and establish regional monopolies.

The gains to Fiji might be short-lived if the other FICs reduced their tariffs unilaterally, entered into free trade arrangements with other countries or joined the WTO. Many of the Islands would be unable to compete. Those who had no alternative means of collecting revenue and depended most on tariffs could face fiscal crises from the combined effect of tariff cuts and trade diversion as more expensive imports from FICs replaced cheaper goods from other countries that still attracted duty.

Anticipated gains to consumers from lower prices might just as easily become higher prices and profits for exporters. Some of these impacts were already apparent with the MSG (Cooke, 2000).

2. A rapidly changing global environment, and the creation of the WTO with its strong dispute settlement mechanism, meant preferential market access arrangements would not continue. The Lomé agreement was on life support with a WTO waiver that would expire in 2000, and the EU had made clear that it would only seek one more renewal. The waiver for the Compacts of Free Association would expire in 2006. The Pacific Islands faced a crossroad. ‘This process is not of our making but we cannot sit there and do nothing while the foundations of our economies are being removed’. A two-step process was identified, one based on MFN liberalisation and one involving trade and economic integration at the regional level. There was no recognition that a deeply flawed neoclassical model of comparative advantage might prove more damaging than pursuing an alternative path.

3. The ‘ stepping stone’ argument made a virtue of the prediction that gains from such a FIC-only agreement would be minimal, by arguing that the adjustment costs would be minimal too. A gradual approach would allow the Island countries to set their own pace and implement the transitional changes and ‘sound’ policies that were necessary for them to participate effectively in the global economy. There would be safety nets to ensure that local industries were not destroyed. An appropriate value added tax (VAT) could make the process fiscally neutral. The starting point would be the MSG, which would be superseded by a more inclusive regional agreement. Levi simply assumed that a gradual approach would make the economic, social and political costs of these policies, and the subsequent exposure to global markets and transnational corporations, more manageable. A ‘stepping stone’ also implied that the destination was identifiable, irresistible, achievable and desirable. The journey which the FICs eventually signed on to with PICTA and PACER would be none of those.

4. The ideological justification reinforced the belief that globalisation was inevitable and the Pacific Islands had to embrace the global economy or be left behind. ‘Whether we create a regional free trade area or not, we have to adjust to a more open global economy or face stagnation and even greater marginalisation.’ The ‘soundness’ of neoliberal policies and the absence of alternatives were also assumed. This was the rhetoric of the moment. The WTO seemed omnipotent. There was no space to question the orthodoxy; expressing doubt was a sign of ‘bad governance’. There was no recognition that this omnipotence might prove transitory, either.

5. The political rationale operated at two levels. There was a strong belief among FICs and the Secretariat that a free trade agreement would enable them to protect their interests more effectively in negotiations with larger powers, notably the EU, and in the WTO.

The real reason the free trade area should happen is that it is a strong political message that would help arrest the political and economic marginalisation. The more the region acts as a group, the more political influence it will have. A regional trade agreement will be important both economically and politically.

More controversially, some saw a free trade area as an opportunity to streamline and rationalise the bureaucracy in the 14 Island countries and open the way to an eventual political confederation in which Australia and NZ may, or may not, be included. That rationale is now being put to the test.

Page 16

Backroom Bullies

Accounts of the meetings between Australian and NZ government representatives and the officials, politicians and consultants for the Forum Island Countries reveal a pattern of arrogance and intimidation. This was led by the Australians and condoned, and sometimes mirrored, by NZ.

The teams of specialist trade officials from Australia and NZ overwhelmed the negotiators from each Island country. Only Fiji, PNG, Samoa and the Cook Islands reportedly played an active role in the meetings – and they lacked the resources to assess the legal and economic implications of a steady stream of proposals, let alone their social impacts. Even the Fiji government had no specialist trade lawyer to call on. Cultural factors were pivotal. In the Pacific Way, strong opposition to what Australia and NZ were demanding was generally expressed by silence – which Australia and NZ interpreted as consent.

Those negotiators who were prepared to speak out limited their interventions because speaking too often would reflect badly on their country. Political pressure behind the scenes, and the ever-present reality of dependency on Australia and NZ, further fettered their ability to hold the line.

The FICs depended heavily on the Forum Secretariat, whose officers bore the brunt of Australia and NZ’s bullying. The Secretariat faced a quandary. On one hand, its mandate required it to represent all Forum members and adopt a neutral position in what became a highly adversarial process. Technically it did that. But there is no doubt that the Secretariat’s priority, or at least that of its trade division, was to service the needs and preferences of the Islands. Just before the 1999 Leaders meeting in mid-November 1999, for example, Fijian media reported Secretary General Noel Levi as saying that Australia and NZ would not be included until at least 2011. In the pre-negotiations workshop in March 2000 he urged officials not to become preoccupied with whether Australia and NZ were in or out, deeming that a distraction from the real issues.

The Secretariat’s chief trade adviser Roman Grynberg relied more on the legal arguments. If Australia and NZ, as ‘developed’ countries, were involved the agreement would require WTO approval under Article XXIV of the GATT. This required coverage of ‘substantially all trade’ within a period of around 10 years. An Australia/NZ-inclusive agreement that was phased in over a much longer period was unlikely to be approved. A ten year period was beyond the capacity of the Islands to implement. If the EU then demanded MFN treatment for any concessions granted to Australia and NZ, as it was entitled to do under Cotonou, and the US made the same demands of the Compact States, the Forum Island Countries would be forced into a level of liberalisation that was totally unmanageable.

The Forum’s consultants were also targeted. Australian officials demanded a series of meetings with the NZ academics involved in drafting the legal texts for the Forum. NZ officials seemed to tag along. These meetings reached ‘a crescendo of unpleasantness’ when officials from both countries flew to Auckland to express their views about a study on the proposed ‘umbrella agreement’ that the Secretariat had commissioned. In between, the consultants were subjected to a blitz of e-mails.

One describes the experience as follows:

The public behaviour of the Australian officials at some of the meetings was appalling. Their anger at ‘being crossed’ by the Secretariat and the Pacific Island countries was palpable. The not-too-subtle implication was ‘we’ve paid for all of this, why are you being so ungrateful in excluding us’. Their private behaviour, at its worst, descended to levels that I regard as totally unacceptable. The whole experience was stressful and demoralising for me, let alone for the Pacific Islands negotiators. There were times that I felt ashamed to be a New Zealander;

I was just pleased that I was not an Australian.

The Forum Island governments ultimately felt powerless to say ‘no’. A major reason was the lack of pressure from within their home countries. Secrecy works to the advantage of powerful governments. If the bullying tactics and demands of Australia and NZ had been more widely known, negotiators and ministers could have used this to strengthen their hand. Instead, the negotiations were conducted behind closed doors. Consultation was limited to selected members of the private sector. The consultants’ reports commissioned by the Secretariat were kept confidential to the Forum members and effectively remained unchallenged.

Page 17

Turning the Tables on the FICS

Australia and NZ refused to accept that “‘no’ means ‘no’”. NZ Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade files show the text went through at least four major reformulations before they were prepared to let it be signed.

The first text produced for the Forum Secretariat (in January 1999 and refined in June) was confined to trade in goods among the Forum Island Countries. A protocol applied the same provisions to Australia and NZ, minus the flexibility to take emergency measures. That protocol provided for specific schedules of tariff cuts and exceptions that would apply to Australia and NZ. Island governments would ratify the protocol separately from the main agreement amongst themselves. Australia and NZ objected that this denied them the status of full negotiating parties (‘parties principal’) and rejected arguments that their proposal would contravene GATT Article XXIV.

The legal drafters produced an alternative version of the protocol for the Leaders meeting in November 1999. This promised negotiations to extend any trade liberalisation that occurred under the main agreement to Australia and NZ on a ‘mutually acceptable’ MFN basis. Those negotiations would begin no later than 6 months after the FIC-only agreement came into effect. Australia and NZ objected that there was no guarantee that such an arrangement would be in place before any liberalisation commitments were made to the EU. They wanted the core arrangement to be tuned to their needs, rather than negotiating an additional one.

The Leaders instructed the Secretariat to seek feedback from each Island Country on the two options. Australia and NZ were now collaborating more intensively. Australia developed an alternative text, which basically shifted the protocol into the main text and made Australia and NZ full parties principal. They tabled this jointly before the pre-negotiations workshop in March 2000. In support, they argued that the Forum needed to maintain its unity and that the Stoeckel report showed the FICs would get much greater benefits by including them. NZ indicated there were other aspects of the text they also wanted to discuss, such as the inclusion of services.

The Secretariat prepared an issues paper for the pre-negotiations workshop which was openly unsupportive of Australia and NZ’s proposals. Island government officials then asked Australia and NZ to provide further clarification. NZ produced a new proposal for their inclusion as full parties. They accepted the need for separate schedules for any tariff cuts that benefited Australia and NZ and suggested the Islands could reduce their tariffs beyond that level at their own pace, with a view to eliminating them in line with APEC’s 2020 timeline. Once reduced, however, they could not raise the tariffs again, unless the justification came within the emergency provisions of the agreement. Any tariff preference to any other ‘developed’ country would have to be immediately accorded to Australia and NZ. SPARTECA would continue to apply for those countries not immediately adopting the agreement. Full participation by Australia and NZ would also send a strongly positive message to potential investors and enhance the international profile of the agreement.

The Forum’s consultants were asked to assess the two Australia/NZ proposals and the two original protocols against four criteria. They found problems with all approaches. The main reasons were:

WTO compatibility: An agreement that involved Australia and NZ would require approval under the GATT Article XXIV rules on regional free trade agreements and would not meet the requirement that it apply to ‘substantially all trade’ within a 10 year time frame. Even the FIC-only agreement then being proposed would be unlikely to satisfy the (lower) standards the GATT applies to a ‘developing country-only’ agreement.

Trade relations with other developed country partners: The Cotonou Agreement required Pacific ACP countries to extend the same commitments to the EU that it makes in a free trade agreement with any other developed country. The Compacts of Association between the US and Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Palau would apply the MFN rule even where the agreement was only among ‘developing’ countries. The FICs would not cope.

The ‘stepping stone’ approach: The Australia/NZ proposals would not give the Islands the time they needed to adjust to the requirements and impacts of trade liberalisation in a gradual way.

Page 18

The consultants’ assessment of the fourth criteria - the desire of Australia and NZ to participate as parties principa l - put the politics of the negotiations unequivocally on the table. They concluded that the desire to participate was driven by political rather than economic considerations, because the economic benefits which Australia and NZ could obtain as parties principal could also be achieved through the protocol approach. The consultants also identified as an overriding concern the need to ensure that the Islands did not become locked into a trade architecture that could cause them unnecessary problems in the future.

They proposed a completely new approach of three separate agreements that used identical terms. The first would cover trade among the FICs and be signed immediately. The other two, between the FICs and Australia and between the FICs and NZ, would be negotiated within a specified period. This would avoid the requirement for immediate WTO notification and MFN extension of those commitments to the EU and US. Each country would only be a party principal to the agreement(s)

involving them. This complex arrangement was a way to avoid a further problem that an agreement including Australia and NZ would need to cover ‘substantially all trade’ to satisfy Article XXIV. That would have to include almost all trade between Australia and NZ, which takes place duty free under the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (CER). But the Rules of Origin (ROOs) being proposed for the Pacific agreement were more liberal than CER and neither Australia nor NZ was prepared to apply them to TransTasman trade.

To satisfy Australia and NZ’s political objectives, a fourth ‘umbrella agreement’ was proposed that would eventually bring the other three together in a Forum-wide free trade area. This would guarantee that other developed countries did not get preferential treatment over Australia and NZ, and include measures on trade facilitation and economic and technical assistance.

Australia’s Foreign Minister Alexander Downer objected that the proposed structure introduced two levels of Forum members and Australia continued to demand watertight commitments. New Zealand opted to massage the idea of an umbrella agreement to achieve the most favourable compromise. The end product was two agreements: an overriding ‘umbrella’ to which Australia and NZ were full parties, and a ‘sub-agreement’ that was confined to the Forum Island Countries.

The Pacific Island Countries Trade Agreement (PICTA) provides for free trade in goods within 8 years (2010) for all developing FICs and 10 years (2012) from the Small Island States and LDCs. Sensitive products can be protected until 2016. Alcohol and tobacco were exempted for 2 years pending an assessment on the revenue implications of including them. Rules of Origin were set at 40% of value added. Each country’s schedule of tariff cuts and their negative list of sensitive industries was annexed. Only the FICs were parties principal to PICTA. The Compact States were given an additional three years to sign once they had assessed the implications of extending the same concessions to the US. Nine countries originally signed.

PICTA required ratification by at least six and came into force on 13 April 2003. Current parties are the Cook Islands, Fiji, Niue, Samoa, Tonga, Solomon Islands, PNG, Nauru and Kiribati. Vanuatu and Tuvalu and the Compact States have yet to ratify.

The Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) merged the proposal for separate FIC-Australia, FIC-NZ and umbrella agreements. All Forum members were parties principal. PACER promised broader ranging negotiations with Australia and NZ on trade liberalisation and economic integration in 8 years time (once PICTA was in place for ‘developing’ FICs), or earlier if triggered by one of several mechanisms. A separate Annex set out processes for establishing trade facilitation programmes which Australia and NZ agreed to part-fund, along with less detailed commitments to provide financial and technical assistance. PACER required ratification by 6 Forum members, including Australia and NZ – a lower threshold to ensure that it was ratified before the ‘subsidiary’ PICTA. PACER came into force on 3 October 2002, having been ratified by Fiji, Australia, NZ, Cook Islands, Samoa and Tonga. Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, PNG and Solomon Islands have since joined.

PACER is officially portrayed as the dominant ‘umbrella’ agreement under which the Island-only PICTA sits. This was a victory and a defeat for the Forum Island Countries. They had bought time before they had to negotiate anything concrete, with a promise that might never produce an actual agreement. In political terms, however, Australia and NZ had forced their way into an arrangement that was not intended to include them and secured enough leverage to require a further round of negotiations, sooner or later. Their demands would be difficult to fend off a second time, especially if they were based on claims to parity with the EU - even though PACER contains no formal MFN obligation and the impacts of similar concessions to Australia and NZ would be far more severe.

Page 19

The PACER ‘Triggers’

Australia and NZ succeeded in becoming parties principal to PACER and symbolically subordinating PICTA under its umbrella.

That promised the future negotiation of a free trade arrangement - defined as ‘at least one free trade area or customs union, or at least one agreement leading to the formation of such area or union’ consistent with Article XXIV.8 of the GATT. As noted earlier, this requires an agreement to cover ‘substantially all trade’, which by convention must be achieved in a period of 10 years.

PACER has a gradation of triggers. The softest, in Article 14, requires each party to keep the others informed of ‘the implementation of, and progress of, economic integration arrangements’ in which they are involved. This allows Australia and NZ to require information on the implementation of PICTA and any Pacific REPA that comes into being.

A general notification provision applies under Article 6(2) where any party to PACER enters into negotiations for a free trade arrangement with a non-Forum country. The onus to notify is on the party entering the negotiations, so they have the initial power to define whether negotiations have begun and whether those negotiations are for a free trade arrangement; that interpretation could later become a matter of dispute. This obligation applies only to negotiations that began after PACER came into effect in October 2002, or later for countries that accede after that date.

Article 5 has several other ‘soft’ requirements:

- Any party to PACER can notify the Secretariat that it wants to establish a new trade and economic integration arrange ment between all the FICs and Australia and NZ, or extend or deepen the coverage of existing arrangements. How ever, this requires consensus and, given the antagonism towards a free trade arrangement with Australia and NZ, seems unlikely.

- All PACER parties can agree to hold earlier negotiations as part of regular three-yearly reviews. This also requires consensus and seems equally unlikely.

- If either Australia or NZ begins formal negotiations for a free trade arrangement with any non-Forum country it is required to offer ‘consultations’ to each FIC, with a view to beginning negotiations for improved market access.

Australia and NZ have attempted to activate this in relation to their negotiations with the US and Chile/Singapore respectively. But that ‘offer’ is limited to improving market access, such as more lenient Rules of Origin, and has not been taken up - presumably for fear of opening the door to wider negotiations.

The fallback position for Australia and NZ is the requirement in Article 5(1) that all parties to PACER begin negotiations with the aim of setting up reciprocal free trade arrangements eight years after PICTA came into force. This means negotiations would not begin until April 2011 – more than three years after a Pacific REPA with the EU is meant to come into effect - and falls well short of the parity Australia and NZ were demanding.

The more immediate leverage available to Australia and NZ comes from Article 6(3) and 6(4). These require Australia and NZ to be offered ‘consultations’ as soon as practicable, with a view to beginning negotiations for a free trade arrangement, if

- any FIC commences formal negotiations for a free trade arrangement with a developed non-Forum country;

- any FIC concludes a free trade arrangement with a non-developed country whose GDP is higher than NZ’s; or

- all the FICs who are party to PICTA jointly begin negotiations for a free trade arrangement that would include at least one non-Forum country.

The obligation to negotiate ends if the negotiations that triggered them are discontinued.

Forum Island Countries that are not a party to PICTA or PACER are not affected by any of this, although they are allowed to enter into any consultations and negotiations that are triggered by Article 6(3).

Australia and NZ must continue to apply SPARTECA and any other existing market access arrangements with any FIC until they have concluded new or improved arrangements that give that country equal or better market access.

Significantly, the only enforcement mechanism for the ‘triggers’ is the Article 15 requirement for good faith consultations to seek a mutually satisfactory solution to any dispute.

Page 20

PACER’s Principles