Cullen Speech to Union-Government Forum

Cullen Speech to Union-Government Forum

The government puts a lot of store, and a high priority, on lifting New Zealand’s sustainable growth rate. In number terms, we have talked about moving to a four percent per annum sustainable growth track, and through that of eventually moving back into the top half of the OECD in terms of per capita living standards.

If we look at the New Zealand of today, our standards of living are vastly higher than they were fifty years ago. It doesn’t matter what indicator you use: life expectancy; years spent in education; cars per head of population; proportion of income spent on recreation; the purchasing power of the state pension; per capita spending on health or whatever.

The problem is that even though our absolute standard of living has been steadily rising, our relative standard of living has been slipping: other countries, and in our case especially Australia, have been improving their material living standards at a faster rate.

If this continues, the income structure that the better performing economies can sustain opens up a gap on our own. People, and especially the skilled and employable, move away seeking to improve their lot.

As they locate in the higher income centres, business follows them: that is where best market and profit opportunity resides. We end up with a negative cycle: labour and capital relocating in the better performing economies, further driving that better performance and widening the relative income gap.

From the perspective of industrial and political Labour, this gap is particularly worrying. If we have a certain national income pie, and some essential skills are highly mobile across the Tasman, there is an irresistible tendency for the distribution of income to become less equal. It is a trend that we end up tolerating, rather than designing or approving.

Of course we need to avoid the doomsaying aspect of this. People will not only live here, but will seek to come here, because it is a great place to live. Not only is it still a developed high-income country in the broader global scheme of things, but New Zealand has many non-tangible quality of life aspects that both retain and attract its citizenry.

The problem is that society builds expectations around what other people have: in things like access to health services, and about what constitutes a decent level of consumption of goods and services. If growth does not enable those expectations to be met, the result is an internal squabble over bigger bits of the inadequate pie. So we must grow.

There has, of course, been quite a bit of theoretical argument and empirical questioning about what causes growth. The conclusion is that there is no magical formula, and no single answer. Both high and low tax countries have shown good and bad growth performances. Highly centralised and highly decentralised wage fixing regimes have co-existed with both high and low growth. So with light and relatively heavy regulation.

There is probably a consensus around the necessary conditions for growth. No economy with persistent inflation, or with chronic imbalances in its public finances, can grow for long. Clearly defined property rights and a well functioning legal system to enforce them are essential. We need administrative systems, in private as well as public organisations, that are transparent and free of corruption. The question is what more is needed.

In New Zealand, there has been a persistent refrain that in order to grow, we need to follow the neo-liberal route to growth: low taxes, as little regulation as possible, the privatisation of as much economic activity as possible, and a minimalist state. That influenced the design of policy in the late 1980s, and dominated it in the 1990s.

The present government does not want to adopt this model for two fundamental reasons. One, it is not a desirable route when we take account of our perfectly legitimate other objectives: protection of the environment, and an equitable distribution of income, wealth and power. The second reason is that the model does not work.

One Treasury report that was sent over to me recently contained a review of a book by a visiting economist that I was due to meet. I hadn’t heard of the gloriously named J Bradford DeLong from the University of California before, but a paragraph in his review certainly struck a chord with me.

“There is a sense in which neoliberalism as we know it is a counsel of despair. Most of what is needed is beyond its reach. The hope is that privatisation and world economic integration will in the long run help create the rest of the preconditions for successful development. But we are playing this card not because we think it is a winner, but because it is the last one in our hand.”

That leads on to what the preconditions that neoliberalism cannot reach might be. I suspect that they will differ from country to country depending on a number of factors: how big they are, how close they are to larger markets and so on.

The growth literature I have seen identifies two other preconditions that are reasonably consistent across most nations: energetic investment in collective goods and a national consensus for growth.

I will start with public investment. This fell away sharply during the 1990s, and the associated short-term savings were essentially dissipated through rounds of tax cuts. There is no evidence that this lifted our sustainable growth rate. There is plenty of evidence that it left the incoming government with a massive bill for deferred maintenance.

We have had to rebuild and re-equip across the spectrum of collective goods: public housing, schools, hospitals, roads, defence force equipment, corrections facilities and the list goes on.

This has put a lot of pressure on our capital budget, and has meant that if we are to keep debt under control we need to run operating surpluses large enough to finance at least a part of the capital spending and/or find other ways of financing the programme.

A robust infrastructure is an essential contribution to improved productivity: a fact that our Australian neighbours never tire of gloating about.

Because we have a strong commitment to quality investment in collective goods, there is always pressure on the amount of extra operating expenditure that we can afford, at least in the near term

The second element of that something more that is needed is the national consensus. In some countries that is just a shared understanding: it isn’t formally written down or signed up to. But in a number of cases these national agreements are rather formal. I am thinking of examples like Ireland, the Netherlands and Australia during the Accord years.

Whether we have a formal social compact, contract, partnership or whatever, I am firmly of the view that we will not grow if society is divided against itself. There is just too much negative energy expended around short-term contests for a piece of the action. That is why work on an inclusive economy and on promoting social cohesion has to be seen as an indistinguishable part of our economic project.

It is why I have persistently rejected calls to cut the top tax rate as the means of stimulating growth. I have never understood the logic that says that people who have lots of money – more than they really can spend – will work harder and longer and take more risks and be more adventurous if you give them some more, but people who are battling to make do from day to day are somehow indifferent to how much tax they pay.

Nobody wants a higher tax rate than is necessary. We have to be aware that if we drive too big a tax wedge between here and other countries, there will be a degree of economic relocation. We do need to keep our tax laws up to date to protect the revenue base. But with those qualifications it is time to close the book. We are not an overly taxed country. Our taxes are relatively simple and transparent and are not augmented with an array of disguised levies and charges.

Our programme for growth is therefore based on sound fundamentals, a commitment to energetic investment in collective goods and on the need to build and maintain a broad social consensus around not only the need for growth, but on an acceptance that contributions to and rewards from growth are fairly shared.

It also rests on an explicit belief that economic growth does not simply happen. It has to be nurtured. While the government does not deliver economic growth, it both makes a contribution to growth and fosters and facilitates growth by coordinating and supporting the actions of private sector players.

That role was specified in the growth and innovation framework that was published earlier this year.

I am not going to describe the whole framework, but want to give some overview of it. We get to a higher growth plane by lifting the quantity and quality of our labour force, by increasing the capital stock, and by improving productivity.

Productivity will improve if we lift our game in four key areas: skills, new investment, improved infrastructure and broader export opportunities.

It will improve further if we do two things well: strengthen the foundations of a modern economy and work on our natural advantages and aptitudes. The framework identifies three areas where this competitive advantage needs to be developed: biotechnology, communications and information technologies and the creative industries.

That is fine as it goes, but it leaves unanswered the question of where unions fit into the process by which the framework is developed, implemented, monitored, and refined.

The CTU is articulating a vision of union relevance beyond the level of negotiating collective agreements. That means relevance on a broader range of issues, and relevance at different levels of the policy process.

One of the big challenges is how to make that exercise of relevance consistent. By way of example, how does a union input into the content of a collective bargain line up with the requirements to remain an attractive destination for inward investment, and contribute to the longer-term goal of raising productivity?

There is neither an easy answer or a single formula.

I am acutely aware of the need to avoid designing a regime that expects a contribution from unions – let us say in the form of collective restraint of some sort – that is backed by rather intangible payoffs in return.

Unions don’t control many of the other levers that lead to investment, new jobs and new work practices. Of course we can meet and talk, often and at many levels. But that equally can lead to mounting frustrations – on both sides of the equation.

I want to return to that idea that I raised a month or so back, about some sort of social compact. Let’s not get hung up on the words, whether it is a partnership, dialogue, conversation and the like. The context was my appearance before Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Select Committee. The Opposition was trying to push the standard neo-liberal solution to growth and I was asked what I thought had driven growth in other countries.

My response was that the dominant feature of many successful small economies was the contribution that social compacts had made to their performance.

This has led on to quite a bit of media interest in the prospects for one here. I would make four observations about such arrangements. They have to be relevant to the institutions, cultures and traditions of the specific countries they operate in. There is no single international standard model.

Secondly, they need to relate to the specific problem or problems that a country is facing at the time they form. They are not just about, for example, wage controls. Third, they need to evolve as circumstances change. Finally, if they are no longer needed, there is no need to try and sustain them. The fact that a compact has been terminated does not mean that it failed. It is just as likely that its work is done.

Many of the high profile compacts emerged during times of economic and social crisis. That tends to concentrate the mind. In New Zealand we are in a relatively benign economic environment. Despite global economic conditions, we are operating with low unemployment, a high labour market participation rate, good fiscal surpluses, modest public debt, low inflation and a lowish balance of payments deficit.

So why change? The reason is that we are trying to reverse nearly half a century of mediocrity. This means that there is a much greater need for greater public awareness about the importance of our mission. In these circumstances, dialogue and explanation become as important as negotiation and compromise.

We do not have a centralised wage fixing system, and I am not aware that any credible economic commentator is arguing that wage inflation is our core problem. Under these conditions, any partnership arrangement is less likely to involve an agreed wages path.

My initial feeling is that what we lack is connectedness. Policies are pursued in their own right. We should not make decisions on – say – the length of the working week or year, without connecting that to decisions about what we are doing to raise productivity. Yet we do.

We have to connect decisions on spending with the need for financing infrastructural investment. We should not on the one hand pay lip service to the need for expanding export markets and on the other try and put excessive restrictions on the terms of any closer economic partnership that we might negotiate.

If we do want to accelerate the timing of investments in roads and other elements of the infrastructure, we have to have an open mind about new ways of designing, financing and operating them – for example as provided through the public private partnership model.

Let me make it perfectly clear that I am not advocating that we subvert all principle in the name of fostering growth. The very thing that differentiates our brand of economic policy from that of the last decade is that it is principled, inclusive, and fair. We view economic policy through a wide lens. What I am saying is that we must be clear about what it is we are doing, why we are doing it, and what the costs of doing it might be.

I don’t have any firm views about how formal any structures that we may use to conduct this dialogue need to be. This is something that we can talk about in the workshop sessions today.

I have much firmer views that any dialogue will very quickly degenerate into frustration and recrimination if participants do not participate with a flexible mandate. We need a problem solving orientation. This in turn means open minds about whether or not particular problems exist, their precise nature, and what the strengths and weaknesses of possible solutions might be.

The presentation of fixed institutional positions is not consistent with constructive engagement. Predetermined views on the acceptability of particular instruments also cramps dialogue. This is not all one way. I suspect that the conditions needed to make social discourse work put very much the same pressures on the government side of the table to change the way that problems are analysed and solutions evaluated.

Finally, if we move away from a highly specific social contract type structure, around some type of wages path related to tax, and social wage trade offs then we are looking at more participants that simply the government, the employers and the unions.

An effective social dialogue must involve all relevant perspectives, and this inevitably means a wider set of participants, such as local government and voluntary and community organisations. I don’t have firm views on just how wide we cast the net in this regard, or on whether we end up with a number of different structures with different clusters of participants in them.

I have been arguing today that the debate on economic growth has moved on from the search for single solutions and quick fixes. It hasn’t quite settled on the mix of policies that are needed to achieve growth. Indeed, part of the emerging consensus is that there is no settled mix: the things that are needed vary from country to country and change over time.

We are looking for the set of factors that work in this place at this time. We believe that we have identified them – at least at the high level – in the growth and innovation framework. It is now a question of filling in the detail, implementing the programme and building a shared commitment to it. We look forward to working with you on all three aspects of this next phase.

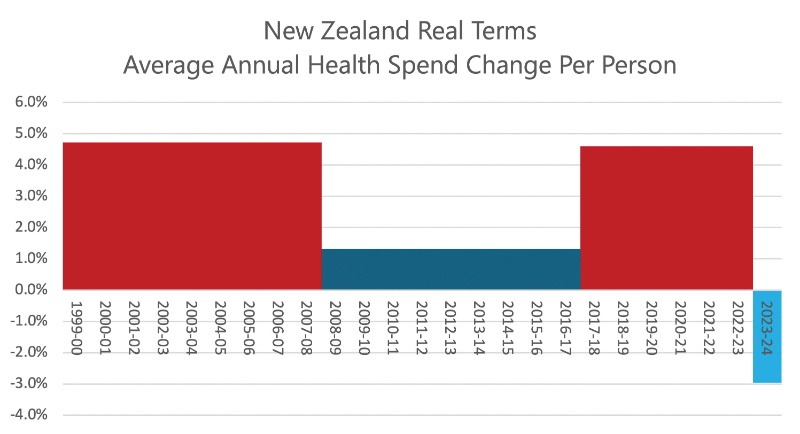

Gordon Campbell: On The Americanising Of NZ’s Public Health System

Gordon Campbell: On The Americanising Of NZ’s Public Health System NZ Labour Party: Govt Health And Safety Changes Put Workers At Risk

NZ Labour Party: Govt Health And Safety Changes Put Workers At Risk Amnesty International Aotearoa New Zealand: Democracy At Risk

Amnesty International Aotearoa New Zealand: Democracy At Risk Walk Without Fear Trust: New Sentencing Reforms Aimed At Restoring Public Safety Welcomed

Walk Without Fear Trust: New Sentencing Reforms Aimed At Restoring Public Safety Welcomed Rio Tinto & NZAS: Archaeological Project Underway From Historic Excavations At Tiwai Point

Rio Tinto & NZAS: Archaeological Project Underway From Historic Excavations At Tiwai Point New Zealand Deerstalkers Association: NZDA Urges Hunters To Prioritise Safety This Roar Season

New Zealand Deerstalkers Association: NZDA Urges Hunters To Prioritise Safety This Roar Season PSA: 1000 Days Since Landmark Pay Equity Deal Expired - Workers Losing $145 A Week

PSA: 1000 Days Since Landmark Pay Equity Deal Expired - Workers Losing $145 A Week