On The Pacific Islands Forum Gathering

In recent months, China has been widely portrayed as a major strategic threat to the Pacific region, yet the Pacific states themselves beg to differ. Pacific leaders insist that climate change is a far more pressing existential threat. A month ago, Fiji’s defence minister Inia Seruiratu made that point very forcefully: “Machine guns, fighter jets, grey ships and green battalions are not our primary security concern.”

The real threat to the region’s security and its dreams of prosperity, Seruiratu continued, was climate change. “Waves are crashing at our doorsteps, winds are battering our homes, we are being assaulted by this enemy from many angles…”

As Pacific leaders meet in Suva this week for the annual Forum gathering, this focus on climate change will put pressure on the Australian and New Zealand delegations to match their fine words with actions. Australia for instance, is still the world’s third largest fossil fuel exporter yet until very recently it had some of the weakest emissions reduction targets in the developed world.

As the Australian Climate Council NGO pointed out in a report released late last week, the total climate change emissions by Australia (on 2019 figures, nearly 590 tonnes annually) and by New Zealand (83.2 tonnes) have continued to dwarf those of the rest of the Pacific nations combined, which was responsible for only 28.7 tonnes of emissions in 2019. We’ve long been more part of the problem than part of the solution.

To gain credibility with Pacific nations, the new Albanese government will have to significantly cut its emissions at home over the course of this decade, while also taking the lead in global forums to press others to do likewise. At this Forum meeting in Suva for instance, will Australia and New Zealand agree to put their weight behind the Pacific’s emissions targets at the COP 27 meeting in Egypt in November? New Zealand of course, has its own credibility problems on climate change. Our reluctance to tackle farming emissions significantly or with urgency is well known to our Pacific neighbours.

In a similar vein, the Climate Change report argues that “Based on its high emissions, economic strength, and vast untapped opportunities for renewable energy, Australia should aim to reduce its emissions to 75% below 2005 levels by 2030.” That would be well beyond the 43% cuts in emissions by 2030 that the Albanese government is currently talking about. Even the newly elected and climate conscious “teal independents” have been asking for Australia to make only a roughly 60% reduction in emissions this decade.

Similar credibility problems surround the efforts of Australia and New Zealand to present themselves as the first partners of choice on strategic security issues at the Forum. Given their own trade dependencies on China, Australia and New Zealand are hardly in a position to warn Pacific leaders against the dangers of becoming too reliant on China when it comes to trade, and to the funding of infrastructure projects.

Moreover, if there’s an inherent risk in co-operating with external powers, the Morrison government somehow saw fit to join a new military pact (AUKUS) in the Indo-Pacific alongside foreign powers like the US and UK. It did so before alerting its Pacific partners that this new pact even existed, let alone before consulting with them about what implications AUKUS might have for their interests.

Finally, the new Albanese government is currently seeking to mend fences with Beijing after the diplomatic debacles of the Morrison years. Presumably, this means it will be reluctant to cry wolf about China at the Suva gathering.

Not that differences won’t be aired in Suva. Time will tell, but this 2022 Forum gathering still looks more like an occasion for Australia and New Zealand to start mending their diplomatic fences with the Pacific, while leaving the building of any new fences against China for another day.

Suva Strategies

The Forum meeting’s deliberations will be taking place against a background that includes (a) the recent change of government in Canberra (b) China’s emergence as a valid presence in the Pacific, and (c) the possible defeat of the Bainimarama government at elections due in Fiji later this year. Besides climate change, the post-Covid revival of Pacific tourism will also feature in the formal and informal discussions.

Although China will barely rate a mention in the Forum’s formal business, there is little doubt that the small nation states of the Pacific are privately welcoming the advent of China as a real (or imaginary) player in the region. Already, the China bogey is serving as a wake-up call to the Western powers who have dominated the regions’ affairs for the past 70 years or more.

That wake-up call was overdue. If alleviating poverty is a key marker of success, the neo-colonial relationship with the West hasn’t been a fruitful one for the small nation states of the Pacific.

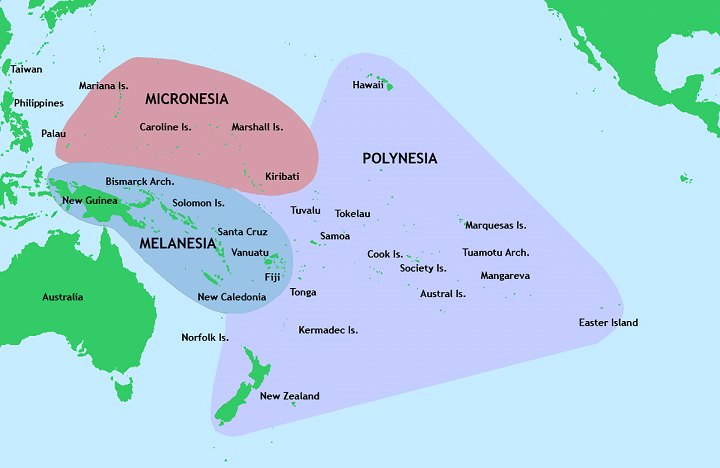

In the post-WWII carve-up of the region, Americans got the North Pacific – Hawaii to Guam and through the rest of Micronesia, while Australia gained a dominant role in Papua New Guinea, the Solomons and the rest of Melanesia. New Zealand’s significant sphere of influence has been the small Polynesian states of the South Pacific. (France has its own colonial legacy in New Caledonia and French Polynesia.)

As Bloomberg News recently pointed out, it is hard to argue that the Pacific region has benefitted all that much from such arrangements:

Thanks to their geographic isolation and minuscule populations, Pacific states do far worse than small island countries elsewhere in the world. Outside Fiji, tourism is rudimentary; to this day, most goods exports consist of fish, coconut and pearls. The offshore financial centres that helped make Mauritius and many Caribbean countries relatively wealthy were stamped out here before they got established. [Or in the case of Vanuatu’s tax haven, were stamped out in 2019 before they reached critical mass.] Income levels, when adjusted for the relatively high cost of living, are on a par with sub-Saharan Africa.

Regardless, the US, Australia and New Zealand continue to regard their stewardship of the Pacific as benign in nature. As a survival tactic, the Pacific island states have learned how to act individually (and as a bloc) to win concessions from the larger powers who routinely come seeking their votes in a range of multilateral contexts from the International Whaling Commission to the Small Island Developing States grouping at the UN.

The statecraft required to do this asymmetric strategizing means that the small island states have become adept at playing the larger powers off against each other. New Zealand may think China’s “intervention” in the Pacific began with the much ballyhooed security pact that Beijing recently signed with the Solomon Islands. Yet the small island states have been involved for years in diplomatic dances with Beijing over (for example) the Taiwan issue.

In 2019, Kiribati and the Solomon Islands both switched their diplomatic allegiance from Taiwan to mainland China in return for China’s investment in aid projects. On the shrinking list of 15 countries that currently recognise Taiwan, four of them - the Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau and Tuvalu – are Pacific countries. The romancing by Beijing therefore, is likely to continue.

In sum… If history is anything to go by, the small Forum states at the Suva gathering will be seeking concessions from Canberra and Wellington for displaying a semblance of re-commitment to the region’s traditional security alliances, while – at the same time – insisting on their independence to strike deals with whoever they choose. Their sovereign right to do so will be respectfully stressed by all leaders present at Suva. Competition can be so rewarding.

Footnote One: The language of the Suva gathering will be dominated by the “Blue Pacific” concept, and by precedents like the Biketawa declaration signed at Kiribati in 2000, and also the 2018 Boe declaration on regional security. Incidentally, the Boe communique also put climate change at the top of the region’s priorities. Such words come cheap. Over the subsequent four years, not much has been delivered by way of meaningful solutions to the Pacific’s problems with climate change.

Footnote Two: The “The 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific” concept has tried to make a strength out of the region’s small land masses, dispersed populations and vast oceanic realms. For development purposes, it aims to treat the Pacific as a unified “maritime continent.” Again, to quote the Climate Council report on the Blue Pacific concept:

Island countries are often portrayed as small, isolated and vulnerable. However – drawing on cultural and economic connections with the ocean – Pacific countries have asserted a contemporary identity as ‘large ocean states’ with sovereign rights across a large part of the Earth. Drawing on pre-colonial relationships across the ocean, Pacific leaders have committed to working together as a ‘maritime continent’.

Right. Yet given that these are not dissimilar concepts to the ones China uses to justify its claims to the South China Sea, it will be interesting to see how the US, Australia and New Zealand manage the free transit implications of the “Blue Pacific” concept, if and when it ever becomes a meaningful reality.

Footnote Three: There is no reason to think the role played by China in the Pacific would be any more benign than that played by Western powers to date. Much of Africa, and the likes of Sri Lanka and Pakistan that initially welcomed investment from China have been left with debt burdens and with under-utilized infrastructure. Moreover, as Bloomberg News also points out:

“China isn’t obviously a better actor on the single biggest issue for island governments, either — the global warming that threatens the very viability of some of the more low-lying states.”

Footnote Four: Finally, the speech that PM Jacinda Ardern gave last week to the Lowy Institute in Sydney has deserved more attention than it got. Basically, Ardern tried to identify a pathway for New Zealand through the diplomatic challenges we face from being a small player in global geo-politics, but a large player in the context of the Pacific.

The gist of her speech argued that while this country will continue to support the collective actions taken through multilateral organisations (and in line with a rules-based international order,) these are always going to be imperfect instruments – and when they fail, the major powers cannot afford to divide the world into monolithic blocs and expect everyone to pick sides.

Instead, Ardern argued, the networks of relationships created by aid, trade and shared values can offer means and avenues of disputes resolution that can be the best bet for averting open conflict. In her view the Pacific Islands Forum offers just such a model:

New Zealand is committed to the Pacific Islands Forum as the vehicle for addressing regional challenges… The model exists, we need to use it.

Interestingly, Ardern also offered the Forum as a useful tool to dial back – rather than to accentuate - the rhetoric being used recently against China:

That is not to say that there will not be others who have an interest in the Pacific – there are. France, Japan, the UK, US, and China have all played a role in the Pacific for many, many years. It would be wrong to characterise this engagement, including that of China, as new. It would also be wrong to position the Pacific in such a way that they have to ‘pick sides.’ These are democratic nations with their own sovereign right to determine their foreign policy engagements. We can be country neutral in approach, but have a Pacific bias on the values we apply for these engagements.

Even issues like the militarisation of the region, Ardern suggested, should not be handled unilaterally [as some would say the Morrison government had done] but should be managed via the Forum’s established procedures:

…Issues that affect the security of all of us, or may be seen as the militarisation of the region should come through the PIF as set out in the Biketawa and Boe declaration, as such a change would rightly effect and concern many. Ultimately, rather than increased strategic competition in the region though, we need instead to look for areas to build and cooperate, recognising the sovereignty and independence of those for whom the region really is home.

Even when conflicts do arise, Ardern argued, the world cannot afford to paint them in black and white terms. This led her into a fascinating aside on the war in Ukraine that’s worth repeating in full:

The war in Ukraine is unquestionably illegal, and unjustifiable. Russia must be held to account, and we all have a role to play in ensuring that that happens. This is why New Zealand will intervene as a third party in Ukraine’s case against Russia in the International Court of Justice. We must reform the United Nations so that we don’t have to rely on individual countries imposing their own autonomous sanctions. We must also resource the International Criminal Court to undertake full investigations and prosecution of the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Ukraine.

So far, so predictable. But then comes this digression:

But in taking every possible action to respond to Russia’s aggression and to hold it to account, we must remember that fundamentally this is Russia’s war. And while there are those who have shown overt and direct support, such as Belarus, who must also see consequences for their role, let us not otherwise characterise this as a war of the west vs Russia.

It is not a war of democracy vs autocracy either, Ardern argues. Nor in her view, should the Ukraine war be taken as the “inevitable trajectory” down which other areas of geo-strategic rivalry are headed:

We won’t succeed, however, if those parties we seek to engage with are increasingly isolated and the region we inhabit becomes increasingly divided and polarised. We must not allow the risk of a self-fulfilling prophecy to become an inevitable outcome for our region.

Of course, this approach of diplomacy and de-escalation offers no sure-fire guarantee of success. Yet at least the Lowy speech is a sign of a leader willing (and able) to think her way through what a small country can bring to the geo-political table, by way of a well-articulated alternative to the route of further polarisation and armed conflict. As she says, she’s had a lot of time to think on her long plane trips lately.

In passing, the Lowy speech also once again illustrates the vast gap in ability between Ardern and the person currently vying to succeed her as PM. Agree with her or not, at least Ardern isn’t reliant on cue cards, slogans and consultants for the content of what she says and does.

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Antithesis Of What Jesus Taught And Lived

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Antithesis Of What Jesus Taught And Lived  Ramzy Baroud: The West Bank's Men Of The CIA - Why Is The PA Killing Palestinians In Jenin?

Ramzy Baroud: The West Bank's Men Of The CIA - Why Is The PA Killing Palestinians In Jenin? Binoy Kampmark: Concentrated Markets And Iceless Fokkers

Binoy Kampmark: Concentrated Markets And Iceless Fokkers Binoy Kampmark: Catching Pegasus - Mercenary Spyware And The Liability Of The NSO Group

Binoy Kampmark: Catching Pegasus - Mercenary Spyware And The Liability Of The NSO Group Ramzy Baroud: The World Owes Palestine This Much - Please Stop Censoring Palestinian Voices

Ramzy Baroud: The World Owes Palestine This Much - Please Stop Censoring Palestinian Voices Dee Ninis, The Conversation: Why Vanuatu Should Brace For Even More Aftershocks After This Week’s Deadly Quakes: A Seismologist Explains

Dee Ninis, The Conversation: Why Vanuatu Should Brace For Even More Aftershocks After This Week’s Deadly Quakes: A Seismologist Explains