On Rabuka’s Possible Return In Fiji

Fiji signed onto China’s Belt and Road initiative in 2018, along with a separate agreement on economic co-operation and aid. Yet it took the recent security deal between China and the Solomon Islands to get the belated attention of the US and its helpmates in Canberra and Wellington, and the Pacific is now an arena of major power rivalries.

There is still ground for the US and its regional allies to make up in Fiji. China had quickly supported the takeover by military commander Frank Bainimarama in 2006, and Beijing expanded its aid and diplomatic support during the years that Australia and New Zealand continued to bewail the coup. No doubt, the recent spectre of Chinese influence in the Solomons helps to explain why (six weeks ago) Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta chose to make her first official trip to Fiji.

During that recent trip, Fiji and New Zealand signed a partnership deal signalling co-operation on matters like regional security, climate change and the Covid response. However, it remains to be seen whether Bainimarama and his ruling Fiji First party will still be in power to implement this so-called “Duavata Partnership.” Within Fiji, campaigning has already begun for an election that has to be held sometime between July 9, 2022 and January 9, 2023.

At the last election in 2018, Fiji First’s governing majority had already been trimmed to only five seats within the 51-seat Parliament. Political polls are rare events in Fiji, and they have an alarmingly wide margin of error – of between 10% and 20%, according to some observers – but the last Fiji Sun poll signalled a slide in support for the ruling party that seems ongoing.

How come? Fiji has been hit hard by the pandemic. Like other governments around the world that have struggled to manage the impact of Covid, the Bainimarama administration has copped blame for its lack of Covid preparedness and response, and for the collapse of the tourism sector that’s crucial to the Fijian economy, and to social wellbeing. Combine that with the government’s notoriously thin-skinned and heavy handed responses to dissent, and it is pretty evident why Fiji First has taken a hammering in public esteem. Some of its problems have been entirely self-inflicted.

And that’s even before you mention the government’s handling of a controversial land reform bill last year that - fairly or otherwise – has also cost it support among indigenous Fijians.

The contenders

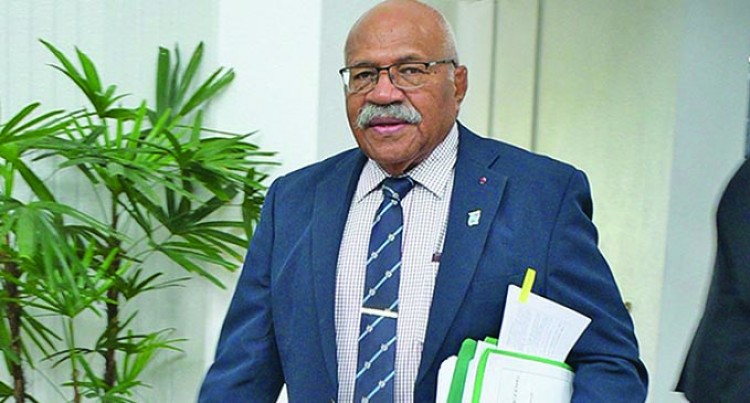

Briefly, four main opposition parties (and a handful of minor ones) are facing off against Fiji First. At the forefront is the People’s Alliance led by Sitiveni Rabuka, the Social Democratic Liberal Party (Sodelpa) led by the relatively lacklustre Viliame Gavoka, the small Unity Fiji Party led by former Reserve Bank governor Savenaca Narube and the National Federation Party (NFP) led by Biman Prasad. The NFP has long been the main party of Indo-Fijians, although it also enjoys support from a small number of indigenous Fijians.

Despite their shared interest in unseating the government, most of the main opposition parties have been wracked by splits since the 2018 election. Rabuka, a former leader of Sodelpa broke away from it in late 2020 to form his own People’s Alliance, after legal wranglings to do with Sodelpa’s constitution and finances had even resulted in the party being briefly suspended from Parliament. At the time, Steven Ratuva, head of Pacific Studies at Canterbury University, had felt wider issues were involved:

Ratuva said Rabuka's resignation was no surprise to him. "It was coming because of the leadership struggle within the party and the multi-layered tensions to do with vanua politics, regional loyalty, personality differences, gender, ethnicity and the generational gap.

"They are all packed on top of each other and Rabuka had to resign as a result of all of these complex tensions within the party.

Alas for Sodelpa, Rabuka’s popularity had been a key reason for the party’s impressive tally of 21 seats at the 2018 election. Reportedly, Rabuka himself accounted for 42.5% of Sodelpa’s total vote. Right now, Rabuka is the main rallying point for opponents of the government.

Sodelpa still appears to be in trouble. As mentioned, its leader Viliame Gavoka is not a magnetic figure. Moreover, and while this issue may (or may not) be significant for many voters, Gavoka’s daughter Ela is married to the country’s most controversial politician, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum - the Attorney General widely perceived to be the most powerful political figure in Fiji, and the driving force within the Bainimarama administration.

Meanwhile, the splits go on. Only last month, the prominent Labasa businessman Charan Jeath Singh broke away from the NFP – for whom he had been an important source of funding and policy advice – and climbed aboard Rabuka’s People’s Alliance bandwagon.

Reportedly, that split had been over Singh’s failed proposal to build support for the NFP among i-Taukei ( indigenous Fijians) by appointing either of two i-Taukei politicians as the leader of the party. Singh’s defection has been taken to be yet another sign of Rabuka’s growing political momentum.

Even so, Fiji First will not go down without a fight. Its highly efficient political machine can expect to receive significant funding support from the country’s corporate sector. While a landslide movement for change in favour of Rabuka is entirely possible, some of the recent speculation has been around whether a coalition government would be necessary in the wake of a close result, and what such a coalition might look like.

Currently, the main opposition parties are united only in ruling out any role within a coalition led by Fiji First, yet some of that disdain may merely be campaign positioning. Post-election, the lure of joining a winning team could prove irresistible, given how few employment options would be available to some of the MPs in the firing line.

Rabuka’s Alliance Party and the NFP have already agreed in principle to be coalition partners if that is required to form a government. Unity Fiji is still mulling over the prospect of joining. Ultimately, as Steven Ravuka told me yesterday, it is conceivable that Sodelpa might also eventually join a “Grand Coalition” of all of the major opposition parties.

Wouldn’t Rabuka’s return to power herald a return to some of the less welcome and racially divisive features of Fiji’s recent past? Not necessarily. According to Ratuva, “Rabuka has evolved as a political figure in terms of his ideas and narratives.” These days, he added, Rabuka’s ties to the military are “pretty minimal” and since the coup in 2000, have even been marked by a certain amount of tension.

Change Partners

At this point in the campaign, the political change on offer by Rabuka and his potential allies is one that’s based on style and attitude rather than on concrete policy. The change on offer is to a more inclusive, less authoritarian style of government, rather than anything based on differences in social and economic policy. Once the party manifestos are issued closer to the still-to-be-announced election date, the policy differences will become more apparent.

Once that happens, the feasibility of a Grand Coalition between parties currently united only by their desire to gain power, will come under pressure. As yet, there has been no inkling as to whether (and how) the existing Constitution might get re-drawn once again, after a new government has been bedded in.

If voters do opt for change, a smooth transition of power would presumably take place. Fiji First, though, has been in power for 16 years and to date, it has never lost an election. While it may take a loss graciously, this is not (quite) a given, given the government’s autocratic tendencies.

No doubt, Bainimarama and Sayez-Khaiyum see themselves as having worked hard and thanklessly to rescue Fiji from its old politics of racial and economic division. In 2013, the country’s Constitution was rewritten along non-racial lines. Fiji First has promoted policies of economic growth that by its own account, have lifted some 100,000 Fijians out of poverty.

So… Post-election, might Fiji First doggedly continue to see itself as the country’s one, true and essential bulwark against a backsliding (under Rabuka) into some of the most negative practices of Fiji’s recent past? Probably not. Yet Fiji First clinging to power regardless is not an totally improbable outcome, either.

Rocky Roads Ahead

Obviously, this will be a crossroads election. Whoever wins power will face major challenges. Even without the damage done to tourism earnings by Covid, Fiji’s poverty levels remain extreme. According to a statistical breakdown that the government - in its usual ham-fisted fashion tried to suppress- deprivation is concentrated among the i-Taukei who comprise a startling three quarters of the country’s poorest people.

For better or worse, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) arm of the World Bank has recently provided Fiji with a blueprint for economic change. Much of it consists of the usual neo-liberal litany of selling off state-owned enterprises to foreign and local investors, creating more public-private partnerships, and cutting jobs and public services in the name of enhanced “efficiency” and productivity gains etc etc. The existing price controls that help to alleviate poverty are also in the IFC/World Bank gunsights : “Approximately one-third of the items in Fiji’s consumption basket are subject to some form of price controls.” Quelle horreur, say the well-fed analysts at the IFC.

On the other hand…

Despite itself, the IFC report also contains some evidence to the contrary. Much as voters may justifiably resent the government’s authoritarian style, the economic results achieved pre-Covid by Sayez-Khaiyum and his colleagues were impressive, at least until these were derailed by the pandemic and by a couple of natural disasters:

Fiji recorded its strongest period of gross domestic product (GDP) growth (since achieving independence in 1970) in the decade leading up to COVID-19, underpinned by rising productivity and investment, improved political stability, and a booming tourism sector. However, the shocks of COVID-19 and a series of natural disasters—Tropical Cyclone (TC) Harold and TC Yasa—have been devastating for Fiji’s economy, bringing widespread production disruptions and job losses.

Climate change, the IFC report believes, will continue to pose major challenges for Fiji in the medium term:

The increasing frequency of these weather events has also complicated Fiji’s economic development strategy and plans. Fiji’s real GDP declined by 15.2 percent in 2020 and is estimated to have contracted a further 4.0 percent in 2021, with the long-term ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy yet to be fully seen.

Even so, some of the immediate impacts of Covid/natural disasters are expected to recede, as the fiscal deficit is forecast to return to near-normality as early as next year:

Fiji’s fiscal deficit peaked at 15.1 percent in 2021 compared to 4.8 percent in 2019, with COVID-19 response measures driving the increase. The fiscal deficit is expected to fall to 6.4 percent in 2023 through fiscal consolidation efforts..

Crucially, the tourism sector was re-opened for business in December 2021. Unfortunately, this was just as Omicron hit the wider world, but the anecdotal evidence is that the sector has been reviving in a robust fashion. The timing of the next election will hinge on whether Fiji First decides to give tourism more time to deliver good news, or whether it will decide to cut its mounting losses by going to the polls early.

Who-ever prevails, the incoming government will then have to decide on just how much of the IFC/World Bank’s medicine it is willing to swallow. It is not an easy choice. Fiji currently has a degree of hard won stability, even if that has (partly) been imposed by it the authoritarian, milittary-backed duo of Bainimarama and Sayez-Khaiyum.

It may soon become more democratic, and a little less predictable. It could also, under Rabuka, be rendered more vulnerable to the strictures of the IFC arm of the World Bank. Frying pan, meet fire.

Footnote One: Some basic facts: Fiji has a population is 908,000, and there are 664,000 registered voters. About 50 % of Fiji‘s population are under 27 years of age. Since Indo-Fijians (reportedly) now comprise only 34% of the population, the election will be won and lost among the i-Taukei (indigenous Fijian) voters who comprise 62% of the electorate. Within the current Parliament, Fiji First holds 27 seats, Sodelpa 21 seats, and the National Federation Party has only three seats – a big disappointment for the NFP, given that it managed to win only the same number of seats in 2018, as it had won at the 2014 election.

Footnote Two: For those interested in the militarisation of the Pacific, this base called Black Rock – it is situated inland midway between Nadi and Nausori – has received only a smidgeon of the media coverage lavished on the Solomons/China security pact. The Australians have recently poured $100 million into Black Rock.

Footnote Three: The threat to Fiji from climate change inspired these observations by the IFC/World Bank:

Fiji is increasingly at risk given the large share of its population living in disaster-prone areas, the climate-sensitive locations of critical infrastructure (e.g., many electricity substations and transformers are located near coastal areas, and a large proportion of transmission lines are still above ground), and the economy’s dependence on agriculture and tourism. It is estimated that about F$9.8 billion will be needed to address Fiji’s climate-change exposure in the next 8–10 years.

Footnote Four: Ten of the 51 MPs in the current Parliament are women, a fairly healthy ratio compared to other Pacific nations, according to Australia’s Lowy Institute think tank. Yet that progress will at risk in the upcoming election :

Fiji is a success story. Women’s representation there has increased to 21.6 per cent. This is a record number of women elected to Fiji’s parliament (ten of 51 seats) and record number running for office (up 36 from the previous election). But while Fiji may now be near-equal to the rate of female representation in the US House of Representatives, there is an election due later this year which may upset Fiji’s progress, as experienced in both PNG’s and Tonga’s most recent elections.

Also, voter authentication amendments made in 2020 to the Electoral Registration of Voters Act stand to (inadvertently) impose requirements that will fall heavily on married women wishing to vote. The problems have to do with the difference between their married names and the names on their birth certificates, and any discrepancy could end up disenfranchising thousands of women voters. In January, it was reported that a constitutional challenge would be mounted to (hopefully) prevent that outcome.

Finally… In the workplace, women’s opportunities in Fiji are relatively restricted. As the IFC report says. women are a growing majority in higher education, but female labour force participation in Fiji is considerably lower than for males (46 percent compared to 83 percent), and that gap is wider in Fiji than in several other Pacific countries.

Binoy Kampmark: Jesting On The Environment - Australian Mining Gets A Present

Binoy Kampmark: Jesting On The Environment - Australian Mining Gets A Present Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Antithesis Of What Jesus Taught And Lived

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Antithesis Of What Jesus Taught And Lived  Ramzy Baroud: The West Bank's Men Of The CIA - Why Is The PA Killing Palestinians In Jenin?

Ramzy Baroud: The West Bank's Men Of The CIA - Why Is The PA Killing Palestinians In Jenin? Binoy Kampmark: Concentrated Markets And Iceless Fokkers

Binoy Kampmark: Concentrated Markets And Iceless Fokkers Binoy Kampmark: Catching Pegasus - Mercenary Spyware And The Liability Of The NSO Group

Binoy Kampmark: Catching Pegasus - Mercenary Spyware And The Liability Of The NSO Group Ramzy Baroud: The World Owes Palestine This Much - Please Stop Censoring Palestinian Voices

Ramzy Baroud: The World Owes Palestine This Much - Please Stop Censoring Palestinian Voices