The Conversation's submission to the Senate Inquiry into media diversity in Australia

Benjamin

Clark, The

Conversation and Misha

Ketchell, The

Conversation

On 11 November 2020, the Australian Senate established an inquiry into the state of media diversity, independence and reliability in Australia and called for public submissions. The Conversation Australia & New Zealand made the following submission to the inquiry:

About The Conversation

The Conversation is a unique global journalism project that in just 10 years has become the world’s leading publisher of research-based news and analysis. We pair professional editors with academics to publish articles that share new research and explain issues in the news. All our content is free to republish, with the aim of sharing trusted information with the widest possible audience.

Since it was founded in Melbourne in 2011, The Conversation has expanded to operate across Australia, New Zealand, the UK, US, France, Spain, Africa, Indonesia and Canada. It is read by more than 25 million people per month directly and more than 64 million per month via republication. In Australia, our editors have collaborated with over 17,540 academic authors.

A unique Australian not-for-profit start-up, our global impact is guided by a clear purpose: to provide access to trustworthy explanatory journalism essential for a healthy democracy.

We place a high value on trust. All authors and editors sign up to our Editorial Charter. Contributors must abide by our Community Standards. We only allow authors to write on subjects on which they have expertise. Potential conflicts of interest must be disclosed.

Our funding comes from partners from the university and research sector, some philanthropic organisations and more than 19,400 individual donors.

The

Conversation team members Tessa, Ben, Molly, Debbie,

Felicity, Ally and Lucy on our October 2019 corporate

retreat.

The importance of public interest journalism in Australia

Quality information is as important to democracy as clean water is to health. Democracy is a decision making process, and without reliable information, voters, bureaucrats, civil society leaders and politicians cannot make informed decisions with surety and integrity.

Public

interest journalism is the primary means by which quality

information is

communicated to the Australian public. It

provides essential context to help people make sense of a

complex and confusing barrage of information. It provides

essential insights that help us understand our politics, our

environment, our culture and our history. It underpins the

health and wellbeing of society.

That is why The Conversation was founded – to ensure citizens and decision makers can freely access quality information written by experts in their field.

The consequences of uninformed decision-making can be dire and, indeed, deadly. A BBC investigation into the effects of coronavirus misinformation found that online rumours led to mob attacks in India, mass poisonings in Iran, physical and arson attacks against telecommunications engineers in the UK, and people swallowing fish tank cleaner and other harmful chemicals in the US. Needless to say, this is not the kind of information environment we want to see in Australia.

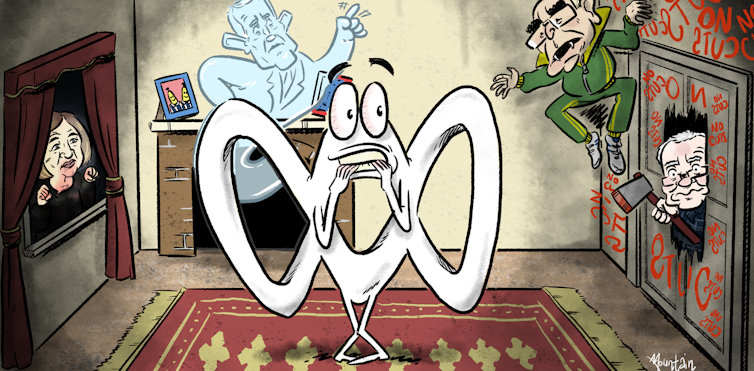

Cartoon

by The Conversation’s Multimedia Editor Wes Mountain,

April 2020.

The public interest journalism ecosystem in Australia

Public interest journalism only flourishes in a healthy media ecosystem. Such an ecosystem is one of vibrant diversity, where many types of media organisations play a constructive role in seeking out and publishing quality information, showcasing different perspectives, and reaching different audiences.

There is a role for the commercial media sector, in particular major publishers such as News Corp and Nine, to balance profitability with integrity for the benefit of broad audiences.

There is a role for public broadcasters, such as the ABC and SBS, to operate within a charter, with fewer commercial relationships. Their role is also to serve audiences that might otherwise be underserved, and cover issues that might otherwise be unreported by commercial outlets.

There is a role for rural and regional media, to connect and inform local communities.

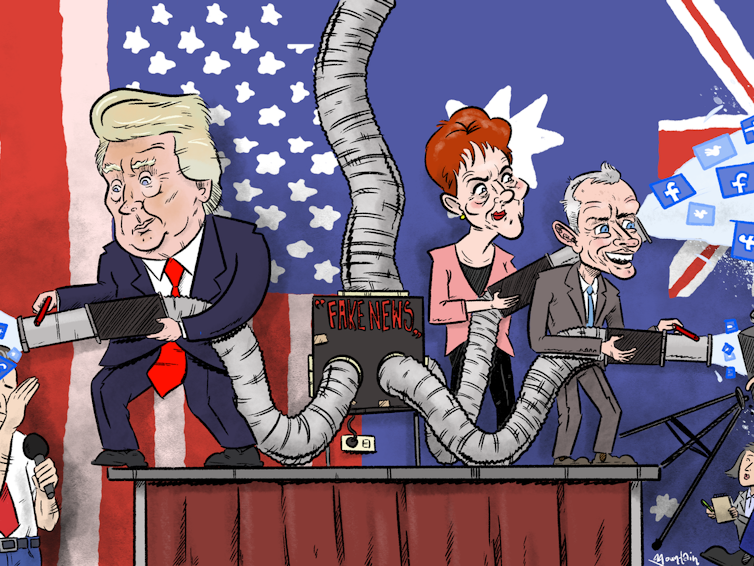

Cartoon

by The Conversation’s Multimedia Editor Wes Mountain,

August 2020.

There is also an emerging role for innovative new players and not-for-profit journalism models, such as The Conversation and the public health publisher Croakey.

The Conversation has carved out a unique role in the Australian media ecosystem. Our mission is to inject academic expertise into public discussion, both via our website and via a network of republishers, such as the Nine newspapers and the ABC.

By partnering with other media organisations across the commercial, public and regional sectors The Conversation helps inject quality information from academic experts into the media ecosystem.

Unfortunately, the range of services and viewpoints Australian audiences have access to has been diminished by closures and downsizing in recent years, which has only been exacerbated by the pandemic.

For instance, there have been significant job losses and program closures at the ABC, one of The Conversation’s top republishers. The Ten network recently closed its online news platform 10 Daily, another former regular republisher of The Conversation content.

AAP, from whom The Conversation sources many of our images, have thankfully been saved from the brink of collapse. All media organisations rely on the health and competition of their peers, but The Conversation’s collaborative model imparts a particular appreciation for our fellow journalists’ work, and we are especially supportive of a broad Australian media market in which dozens of outlets can survive and thrive.

A diverse plurality of individual voices should also be promoted, to ensure that everyone is heard. A platform should be provided for individuals with different cultural, racial, gender, religious and class backgrounds and with different political views. Yet, the media industry does not reflect the multicultural reality of modern Australia.

A recent Media Diversity Australia report, examining an average two weeks of Australian television, found that 75% of presenters, commentators and reporters were of Anglo-Celtic background. Only 9.3% had a non-European background and 2.1% an Indigenous background, compared to 21% and 3% respectively of the broader population. Many newsrooms still have gender, racial and other diversity issues to address.

Read more:

Whitewash

on the box: how a lack of diversity on Australian television

damages us all

A lack of media diversity threatens to entrench the domination of a small number of loud voices in our public discussion. The exclusion of under-represented viewpoints weakens the system and undermines the ability of the media to fulfil its role of providing the quality information that underpins democracy.

A narrow range of voices silences disadvantaged groups and shrinks the ‘Overton window’, the range of ideas that are represented to the Australian public. It can also polarise consumers and make deliberative dialogue harder.

Technological changes have made the business of public interest journalism harder

The increasing dominance of digital tech giants in the Australian media landscape, which has challenged many traditional business models, has only exacerbated these issues. The Conversation has thus been an eager participant in the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s roundtable consultations on their news media bargaining code, and will continue to engage productively with the government, other media organisations and Facebook, Google and other tech platforms to help shape a playing field which is fair to all parties and best supports the flourishing of public interest journalism in Australia.

But the tech giants’ impact on journalism goes beyond the matters contested in the ACCC’s negotiations, to the character of the digital landscape itself.

Most popular tech platforms are designed, somewhat like poker machines, to be highly addictive and extractive. What they extract is our attention, and our attention is increasingly commodified for targeted advertising revenue. These trends have pushed the media toward a paradigm of seeking attention at all costs, even when this involves sharing poor or misleading information. The well-known phenomena of ‘ clickbait’ and ‘ fake news’ are products of this race for eyeballs, which invariably prizes the salacious and outrageous over grounded, measured and informed analysis.

Cartoon

by The Conversation’s Multimedia Editor Wes Mountain,

October 2019.

The Conversation was founded to fight back against these trends and inject the insight and rigour of academic expertise into public discussion. Despite the negative contours of the ‘attention economy’, The Conversation has thrived by packaging quality journalism in fun and accessible ways, and because news consumers increasingly search for and value quality information they can trust in the polluted atmosphere of digital media.

This flawed ecosystem is particularly damaging for young people, who often don’t know who to trust. The Conversation recently participated in an industry collaboration with undergraduate students at Melbourne’s RMIT University, who surveyed over 200 of their peers aged 18-30 on their news habits. Whilst 86.1% agreed news sources need to be trustworthy and reputable, with the top two determinants of trustworthiness being the inclusion of scientific evidence (30.7%) and experts (25.8%), one of the top three issues they identified was concerns over the accuracy of the content they were consuming, the vast majority of which is sourced from social media.

Read more:

RMIT

students help The Conversation reach young audiences

Digital

platforms often suggest the best way to safeguard young

people against

misinformation is by teaching ‘media

literacy’. Teaching media literacy is important, but the

sheer volume of low quality content is conditioning

consumers to adopt a generalised mistrust of all journalism

they might see online, including high quality stories of

paramount importance. A generalised mistrust of journalism

exacerbates a broken media ecosystem by lumping in the good

operators with those who are less

reliable.

Furthermore, it amounts to an abrogation of institutional responsibility – like telling citizens to check their drinking water for contaminants, rather than simply cleaning it up in the first place.

Instead of merely relying on readers’ scepticism, we should be committed to improving the quality of information available to all citizens.

The

Conversation staff supporting the Your Right to Know

campaign in October 2019.

To achieve this we need to think like farmers. We need to use regulation to remove weeds and ensure our information ecosystem is not strangled by misinformation. Fact-checking and regulatory bodies like ACMA or the Australian Press Council are good examples of this process.

But we also need to plant the right sort of crops, and a range of crops, to ensure a healthy ecosystem and a healthy diet of quality information. This is where policy around media diversity is important, as are the important and complementary roles of public broadcasters and small rural and regional newspapers as well as major commercial operators.

This is also where The Conversation plays an important role by injecting academic expertise into the news cycle and by operating primarily in a digital space where misinformation is rife.

Rebuilding trust through expertise

The lack of a robust media ecosystem has

meant that many people who can inform the

public have

been staying away, which has also meant the most informed

and insightful voices often can’t be heard. But for the

health of our democracy, we need to get experts back into

the public sphere so we can have an informed public

discourse.

The coronavirus pandemic has been a powerful reminder of the important role experts can play in public life. When the public, and many decision makers, were confused and scared of this deadly virus spreading throughout our community, epidemiologists, immunologists and other public health and medical experts stepped up to inform the public, provide clear instructions and reassure the fearful of the path ahead. Experts such as Raina MacIntyre, Stephen Duckett, Mary-Louise McLaws, Catherine Bennett, Hassan Vally and Adrian Esterman, once little known beyond their professional circle, and many of whom got their first media experience at The Conversation, have become household names and appeared on countless media outlets around the world.

Read more:

Could

coronavirus bring back our faith in experts?

The

Conversation would like to see this renewed appreciation for

health experts expand into a renaissance of public expertise

more broadly. Why should environmental and climate

scientists not play the same role in public discussion of

climate change, technologists and engineers in public

discussion of artificial intelligence, and sociologists in

public discussion of migration and multiculturalism? There

is no shortage of topics on which Australia could

better

utilise the vast reserves of expertise in our universities

and research institutes such as the CSIRO and Bureau of

Meteorology.

Recommendations

Public interest journalism is vital to Australia’s democracy, and you can only promote it by building a healthy, diverse media ecosystem. That requires public broadcasters, commercial media, rural and regional and bespoke platforms like The Conversation that have a specific role to play in informing public discourse.

There is a clear case of market failure in the Australian media industry. There is clearly a need for the government to play an active role in funding and regulating the media industry. The Conversation thus supports the following measures to support public interest journalism:

Direct support of innovative

journalism via an accessible and transparent process

for

granting deductible gift recipient status for not-for-profit

journalism.

Ongoing, secure and arms-length

support for Australia’s public broadcasters, the

ABC

and SBS.

Creating a fund that is arms-length

from government to allocate contestable

grants for

innovative, quality journalism, in a similar manner to The

Australia

Council for the Arts.

One key area

of focus for this fund should be rural and regional

journalism and

community-based media, working in

underserved markets.

A tax levied on digital

platforms (Facebook and Google) could be considered

to

fund this new body, should sufficient funds not be

available through consolidated

revenue.

The Commonwealth’s decision to grant The Conversation deductible gift recipient status has been vital in allowing us to raise funds from our audience. This is a particularly effective way of supporting public interest media because there is an accountability mechanism built in: success in raising donations depends, at least in part, on the media outlet’s ability to generate trust among readers.

Read more:

From

the editor: get your coronavirus analysis and advice direct

from the experts

The Conversation has previously received funding from the Commonwealth and Victorian governments. This seed funding helped The Conversation attain critical mass while proving our model to universities. As a direct result today 38 of Australia’s 39 universities are current funding members of The Conversation. We are now funded wholly by membership fees and reader donations.

We recognise the important role of government funding to seed new projects and expand existing initiatives. Short term funding horizons, and the need to continue to look for new funders, present serious challenges to media outlets which need to have the institutional strength to publish fearlessly. Longer term partnerships are preferable, with minimum time horizons of 3-5 years.

We thank the Senate Environment and

Communications References Committee for

their

consideration of this important topic, and we

welcome the opportunity to address these issues in more

detail.![]()

Benjamin Clark, Deputy Engagement Editor, The Conversation and Misha Ketchell, Editor & Executive Director, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance

Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land

Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death? Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing

Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing