Book Review: Barbara Sumner's "Tree of Strangers"

Review of Barbara Sumner’s book: Tree of Strangers

$35.00 at Unity Books & Massey University Press

By Gregor Thompson

I bumped into a childhood friend recently in a bar in Auckland. Ordinarily, I live in Wellington but I was on my way to Paris to start a new life. The recent surge in Covid-19 cases in continental Europe has necessarily put that plan on the backburner. Lily told me that her mother had written a book and that I ‘ought to read it. Not knowing what to expect, I came out the other side with an internal obligation to share what I had read.

Having previously worked as a journalist, amongst other things Barbara Sumner is an award-winning documentary producer. Sumner is a multi-disciplinary creative and seems to have a habit of perennially popping up. 11 years after her Oscar short-listed 2009 film This Way of Life, Tree of Strangers is Barbara Sumner’s first literary work. Her newly published autobiography is consistent with her previous work in the sense that it is exceptional.

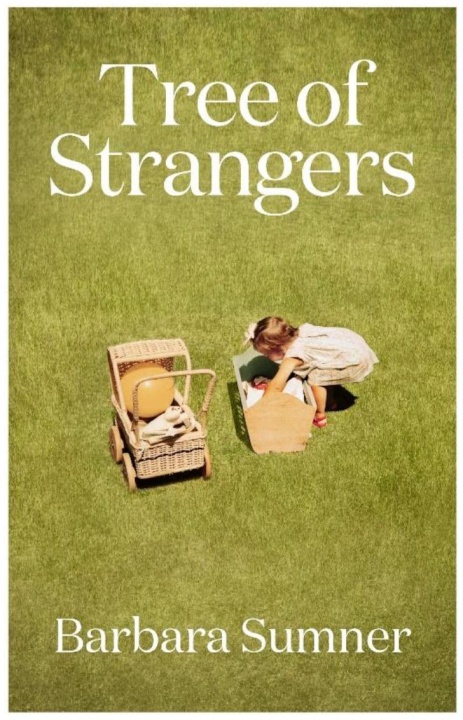

Displayed on the front cover is an image of the author playing alone on a lawn, presumably the backyard of one of her numerous childhood homes. The photo was taken by her adopted father when she was three years old, it conveys an impression of resolute loneliness. Perhaps the perfect portrayal of Sumner’s fascinating life.

Released earlier this year, Sumner’s Tree of Strangers is divided into 27 six-page evocative and deeply revealing chapters that span Sumner’s life: focusing predominantly on the period from just before motherhood to her life as a recent Grandmother living in the Hawkes Bay. Throughout she relates back to stories of an unusual upbringing marred with transiency and personal confusion.

Much of the book focuses on Sumner’s experience of being an adoptee in New Zealand. Over a lengthy narrative arc lasting years Sumner recounts her pursuit of her birth parents as she navigates her way steadfastly through five daughters, three husbands and a diverse range of New Zealand cities and localities. Sumner reveals intimate details from her life that I’m sure validate the experiences of many other adoptees who’s experience of adoption dates to the period of closed adoptions in NZ that is now mercifully largely over.

“If our adopting families cut us loose, we have no legal recourse to our natural parents. No rights to photos, heirlooms, keepsakes or heritage. Our parents’ death certificates will never list us as their next of kin. Our children and their children cannot trace their family trees, except through DNA. We do not exist in the record books. We do not exist at all, except as misshapen fruit grafted onto the tree of strangers.”

Not only is the book important for understanding how extremely complicated the lives of adoptees are, it delves deeply into the difficulty faced by all those closely associated with adoption. Sumner tells of the troubles she had with her adopted parents, reminding the reader of what is often an interrupted and conflicting relationship. She visits and revisits a cruel propensity certain fathers have towards their daughters, ostensibly in the name of family pride.

As she tells her story, she very clearly identifies the cause of the suffering of those involved in adoption, the archaic 1955 Adoption Act. A policy formed on an ideology that total disconnection between adopted children and their biological parents was essential.

“In all, I had over seventy interactions with government departments. The result was always the same. Yes, they had my files. Yes, any staff member could read those files. But no, I had no right to them.”

Sumner describes a system that is asymmetrically balanced to focus on the wishes of adult parents and prohibits the wishes of their adopted children being honoured. The consequences of this are grave, incessant fear of rejection, fear of repeated abandonment among other seriously harmful psychological and associated consequences.

In addressing the adoption complex she ties in several fascinating academic studies, theories and religious perspectives that contribute to and back up her views about the ills of an adoption system that has produced so many perpetually grief stricken and lost individuals.

The book is not entirely about adoption though. Plaited through the narrative is the story of Sumner herself. It’s a distinctive and fascinating story. Passages of her experience as a young woman in New Zealand offer incredible insight into a fiercely resilient, ambitious and creative human being. In particular, the descriptions of her life in Runanga with her first husband Bruce and their three young daughters provide a window into a cultural uniqueness that is facing modern day decline.

Above all else, what makes this book so striking is its honesty. Sumner speaks unapologetically of a subject so often swept under the carpet, and she does so with a raw veracity. I was left with the impression that pursuit of catharsis is part of the reason Sumner shared this story. And it is perhaps this quality that makes it such a moving and impactful read. It certainly doesn’t take anything away from the work and perhaps will encourage others subject to similar circumstance to share their experiences and trauma.

Having read Sumner’s book I far better understand my mother, who had her child taken from her at a young age. I still have not and possibly will never meet my sister. After reading Tree of Strangers, I lent it to my Grandmother whose brother and nephew were adopted; she read it in an afternoon and passed it on to a former colleague who has dealt with similar trauma. Sumner’s story gives important exposure to an inhumane era in this country’s history which is gradually slipping away

To enjoy this book one need not have been exposed to adoption, nor to have even come from New Zealand. Tree of Strangers is delightful and accessible to all. Sumner’s life is so extraordinary that at stages it reads like a novel and is written with the confidence of someone who is accustomed to choosing their path for themselves and someone who understands precisely what they’re talking about.

“I held a sheet of paper to my cheek. It always starts with paper. We crave the provenance of words on a page. Of an artwork, an organic apple, a thoroughbred racehorse. A birth certificate. A family tree. Without traceability, that artwork loses its value. The apple stays on the shelf, the racehorse becomes a nag. Provenance is woven so deep within us, we hardly stop to think what it must be like to exist without it.

I urge anyone to read this book, it may well help save a relationship or two.

ENDS.

Binoy Kampmark: Cowardice And Cancellation - Creative Australia And The Venice Biennale

Binoy Kampmark: Cowardice And Cancellation - Creative Australia And The Venice Biennale Binoy Kampmark: Second Endings - Terminating Neighbours (Again)

Binoy Kampmark: Second Endings - Terminating Neighbours (Again) Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - It's Now Lowest Common Denominator Politics Instead Of Informed Political Debate

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - It's Now Lowest Common Denominator Politics Instead Of Informed Political Debate Ramzy Baroud: Gaza Has Changed The Discourse On Popular Resistance, But Are We Truly Listening?

Ramzy Baroud: Gaza Has Changed The Discourse On Popular Resistance, But Are We Truly Listening? Martin LeFevre - Meditations: What Is A Human Being?

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: What Is A Human Being? Binoy Kampmark: Feeling Very Fine - Picasso The Printmaker At The British Museum

Binoy Kampmark: Feeling Very Fine - Picasso The Printmaker At The British Museum