Gordon Campbell on the Aussie bush fires and Suleimani

Gordon Campbell on the Aussie bush fires, and the killing of Qassem Suleimani

In popular culture, Australia is often portrayed as Western civilisation’s last unspoiled frontier, or as its final refuge from planetary disaster. In Nevil Shute’s best-selling 1950s novel On The Beach for instance, Melbourne served as the backdrop for humanity’s last few hours on earth, before everyone fell victim to the radiation wafting down into the South Pacific from a nuclear war in the northern hemisphere. In recent weeks, the scenes of Australians seeking refuge in the sea from the flames raging across the land have had the same apocalyptic quality. This time though, Australia looks like being the forerunner – and not the culmination - of planetary disaster.

Already, the Australian public has begun to ask its political leaders for answers (long term) and help (short term) to alleviate the extreme conditions that threaten to become the country’s new normality. For his part, Aussie PM Scott Morrison has hardly put a foot right in his handling of the federal government response– from taking a Hawaiian holiday one month after the fires began in earnest, to using its tragic images as the backdrop to a jauntily upbeat video about all the good things his government has been doing to counter the effects of the fires.

As one critic said, the video was like making a sales pitch at a funeral.

Morrison’ ineptitude aside, there is a genuine constitutional problem here. In times of national crisis, Australia’s devolved powers can make it hard to co-ordinate the functions jealously guarded at state level (eg for firefighting) with those operating at federal level, such as for military rescue missions. To some extent, Morrison is being slagged for not doing more to help out state governments that (in the early days of the crisis at least) were telling Canberra to rack off. Subsequently, the Morrison government has reportedly been sending in its aid over the heads of state authorities, without prior consultation, or coherent co-ordination.

Causes,

contributing

factors

What’s caused the

fires, which began to take serious shape at least a couple

of months before the usual commencement of the annual

bushfire season? According to the scientists, man-made

climate change has intensified the drought, intense heat and

strong winds that have been generated by two naturally

occurring phenomena: namely, an unusually cool Indian Ocean

Diapole (IOM) at sea off Western Australia has drawn the

moisture away from the mainland, even as the Southern

Annular Mode (SAM) has intensified the air flows and

temperatures emanating from above Antarctica. Apparently,

the IOM and the SAM have worked in tandem with the

pre-existing drought, and those factors are being

exacerbated by climate change. (If that’s the backdrop

though, why have the IOM and SAM not created effects on

anything like the same scale here? After all, when an El

Nino or La Nina weather pattern is acting as the prime

driver of sea temperatures, we seem to experience them here

to much the same degree as in Australia. Any

comments/explanations appreciated.)

The responses

The scale of the bushfire

tragedy is enormous. At last count, an area roughly half the

size of the entire North Island has been razed. Here’s a US report from over a fortnight

ago:

The New South Wales fires have been burning since September, destroying fifteen million acres (or more than two thousand square miles) and remain almost entirely uncontrolled by the volunteer firefighting forces deployed to stop them….record-breaking heat waves are simultaneously punishing the country (technically an entire continent, Australia as a whole averaged more than 100 Fahrenheit earlier this month) and devastating marine life in the surrounding ocean. “On land, Australia’s rising heat is ‘apocalyptic,” the Straits-Times of Singapore wrote. “In the ocean, it’s even worse.”

Already, smoke has enveloped the city

of Sydney in air at least ten times as thick with smoke

as is considered safe to breathe, setting off indoor fire alarms and

suspending the city’s ferry service, since the boats couldn’t navigate the

smog…

According to the ABC,

fire-generated cloud systems – hello to the adjective

“pyro-cumulus”- have been forming above the south

eastern coast of Australia, with alarming consequences for at least one Melbourne-to-Canberra

flight.

So far, the cost in human lives, housing, livelihoods, and habitat destruction - not to mention the circa 480 million animals that have reportedly perished in the flames - has simply overwhelmed the policy responses on offer. As usual, the public appears to be way, way ahead of the politicians. Well before this year’s fire season began, a Lowy Institute poll published in May 2019

showed that Australians regard climate change as being the country’s biggest threat, ahead of cyber-attacks, terrorism or North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. Yet in both Australia and New Zealand, there is no political appetite for substantively changing the economic settings that keep on generating the greenhouse gases.

For example : while our own Zero Carbon Act has set some laudable long term targets for emissions reduction, the law contains no enforcement mechanisms, and no penalty regime for non-compliance – and the legislation been not been accompanied by any action programme capable of turning its noble aspirations into reality. Quite the contrary. Frankly, if a major corporate had produced a document such as the Zero Carbon Act, the Green Party would probably have been the first to denounce it as greenwashing. Instead, the Greens are touting it as one of their top achievements in government.

Moreover, the Zero Carbon Act was backed in Parliament by National on the understanding among its base that once in government, National would weaken or scrap many of its key measures, and especially those that require sacrifices by the farming community. Reportedly, it was the extent to which National’s former climate change spokesperson Todd Muller co-operated with the Greens (in creating the Zero Carbon Bill) that caused Muller to lose the portfolio.

This yawning gap between the challenge of climate change and the political response had been predicted by Greta Thunberg only months after she began her solo campaign. As she told the UN’s COP24 conference in Poland in late 2018, politicians are running scared of becoming unpopular when it comes to taking significant steps to address climate change. ”Our civilization is being sacrificed,” Thunberg said, “ for the opportunity of a very small number of people to continue making enormous amounts of money.”

Australia has always had bush fires, Australian PM Scott Morrison said in one of his few coherent contributions last week. “But what we are seeing is greater intensity, the season being longer and, unfortunately, this could be the new norm… [and] the national emergency is enormous.” Typically, Morrison then declined to outline what a policy response fit to tackle this emergency might look like.

Clearly, something more than a new federal set of fire risk standards will be required. In the final shot of the film version of On The Beach, the camera pans across a sign that says “There is Still Time, Brother.” By then though, no one is left to read it, let alone to act on it.

Killing

Suleimani

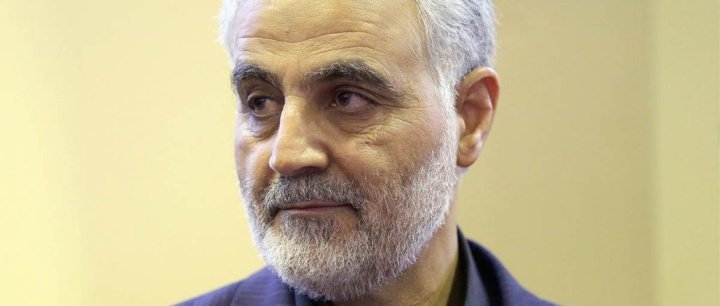

Faced with the

bad impeachment headlines, Trump has chosen to wag the media

dog by finding an opponent to kill. If one was looking for a

rough analogy to the decision by President Donald Trump to

assassinate Qassem Suleimani, it would be akin to Iran, in

2011, choosing to assassinate Barack Obama. Suleiman was

not only Iran’s effective commander in chief, its top

foreign policy and defence strategist, and the head of the

foreign affairs dimension of the Quds Force whose job it is

to defend the Islamic Revolution. He was also the smartest,

most charismatic figure among the Teheran leadership, and

– as such – his abilities ( and patriotism) had largely

shielded him from the hostility being directed nowadays at

the mullahs and at the hapless figurehead government of PM

Hassan Rouhani.

As with Obama, Suleimani’s intelligence and charisma went hand in hand with a capacity for ruthless action. You don’t get to be what Dexter Filkins of the New Yorker reported in 2013 as the “single most powerful operative in the Middle East” by always being a super likeable fellow. When Islamic State and its Saudi sponsors and US/Israeli allies began to threaten Iran’s relatively friendly Syrian neighbour, Iran moved in to bolster the Assad regime, which – before Russia joined the fray – relied almost entirely on Iran and the Lebanese Hizbollah forces for its survival. It was Suleimani who put together that military alliance.

That’s the point. Most of the time, Suleimani’s foreign policy actions – as befits the role he performed within the Revolutionary Guards– were defensive, not offensive in nature. Shoring up Assad in Syria as a bulwark for Iran against the Sunni fanaticism being sponsored by the Saudis, building up Hizbollah as a deterrent and distraction to the Israelis, and extending Iran’s influence within the shambles in Iraq that had been created by the 2003 US invasion, all had a defensive dimension that has been almost entirely neglected by Americans fixated by their own fantasies of Iranian expansionism.

It wasn’t as if Sulemaini had been engaged last week on a secret, covert mission, either. He wasn’t hard to find. He had flown into Iraq on a commercial airline and used his own diplomatic passport. Even this Baghdad mission that cost Suleimani his life had the usual defensive dimension. In the wake of recent attacks on Iran’s diplomatic posts by local mobs protesting about the influence that Iran is exerting within Iraq, Suleimani was orchestrating (with the help of some local militia allies) a counter-campaign of local demonstrations against US facilities. In Suleimani’s thinking, the Iraqi nationalism that opposed Iran’s influence could equally be turned against the US influence and avowed desire to control the region’s oil resources. Essentially, he appeared to be engaged in an attempt at re-balancing, not with opening a major new front of aggression.

In reality – as opposed to US fantasy - Iran is ringed by enemies who are intent on regime change, and on restoring the kind of access to Iran’s oil and resources that the West enjoyed under the Shah. The US had put the Shah on the throne in 1953 via a similar orchestrated campaign marked by creating economic hardship and fostering public discontent. As Mossadegh did in 1953, the mullahs have been playing right into the arms of the American strategy. By murdering Suleimani, the US has removed one of the few capable tacticians that the mullahs had at their disposal.

Footnote: Amidst the media chatter over whether the murder of Suleimani could possibly start a war with Iran, at least a few voices have put that brainless question into perspective. Trump has waged diplomatic aggression against Iran by scrapping the nuclear treaty. The US has also waged economic sabotage against Iran via a sweeping set of sanctions, and has blackmailed allies like New Zealand into falling into line with that plan. We’ve lost a $200 million annual meat trade with Iran as a result, without a peep of protest from National, the farmers’ supposed champion.)

On the thinnest of pretexts, the US has now started assassinating Iran’s key leaders. As Andrew Exum wrote in the Atlantic the killing of Suleimani “’doesn’t mean war, it will not lead to war, and it doesn’t risk war. None of that. It is war.” And Europe and the rest of the West is standing by on the sidelines, urging everyone to stay calm as this war rolls onwards.

Binoy Kampmark: Bratty Royal - Prince Harry And Bespoke Security Protection

Binoy Kampmark: Bratty Royal - Prince Harry And Bespoke Security Protection Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance

Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land

Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death? Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One