First published on The Dig

Image: Banksy (title unknown).

“The top environmental problems are selfishness greed and apathy… and to deal with those we need a spiritual and cultural transformation - and we scientists don’t know how to do that.”

Gus Speth

The disruption and destruction of the interconnected biodiversity of Earth is the most serious challenge humanity has ever faced. This is an ecosystem emergency on an extinction scale. It is also a serious threat to the inherent rights of the diversity of non-human life, ecosystems and human Cultures on Earth to exist and thrive. The current global paradigm is devastating life everywhere by disrupting vital “ecosystem services” like the food, water, and climate regulation systems that both humanity and biodiversity depend on in an interconnected balance. It is increasingly clear that the primary driver of this crisis is the limiting and infectious worldview around land and resource use so central to the global capitalist system. To fully understand the biodiversity crisis and explore what comes next, it is necessary to address this mind-virus at the heart of our modern civilisation – the dominion worldview.

The all-encompassing reach of this infectious dominion worldview has led to a disconnected and degraded planetary ecosystem, and divided, unequal, and traumatised societies almost everywhere. It also renders our global and national political institutions incapable of leading us out of these interconnected environmental and social crises. As Noam Chomsky said recently, we are living in “the most grim moment in human history.”

It is easy to despair in the face of such a stark reality, but, it is also important to maintain hope that we can conserve what is left of the beauty and diversity of life on Earth and enable it to regenerate itself. The disruption of long-established patterns by the breakdown and failure of the dominion paradigm and top-down political structures, in fact, presents an opportunity of monumental consequence to make a transition to a fundamentally different system.

However, this transition will not happen while the disconnected and divisive dominion thinking that created these system failures prevails. Instead, we urgently need a cognitive reframing to flip the script on this maladaptive worldview and build a new one that restores our relationships to the environment and to each other.

The resurgence of "the commons" in parallel to the failing legacy systems of the dominion paradigm offers hope for this transition to a global “ecological civilization.” This resurgence is underpinned by an emergent worldview we can term "cooperatism" - based on tenets of freedom, interconnection, belonging, and collaboration. Cooperatism offers humanity a pathway to healing the planetary ecosystem and uniting behind a common purpose - potentially a Global New Deal for The Commons. The many examples of this emergent paradigm outlined below demonstrate that a transition is not only possible, but already underway... and often in unexpected places.

Contemplating Collapse

“Ecosystem loss has taken place at catastrophic scales warranting emergency response. It is not a future issue: it’s happened and is happening.”

- Will Marshall

The threat of extinction and total ecosystem collapse is very real. Deforestation of the Amazon is nearing an “unrecoverable tipping point", wildfires rage across the world and thawing permafrost has turned the Arctic into a net carbon emitter. The UN Biodiversity (IPBES) Report released this May provides pretty sobering statistics. Since 1980, global biomass of wild mammals has fallen by 82%, natural ecosystems declined by 47%. Live coral cover on reefs has nearly halved over the past 150 years.

A new model released this month by Stanford University predicts this loss will lead to food and water shortages for five billion humans (particularly in developing nations least able to deal with the consequences) in the coming decades and place one million species (25% of all species) at risk of extinction.

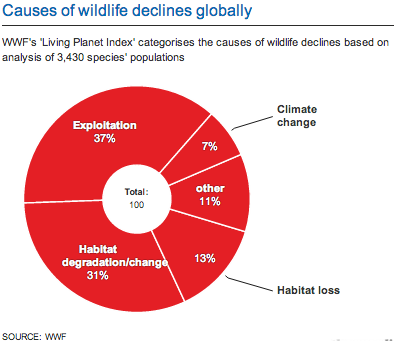

WWF's Living Planet Index indicates that the single biggest contributor by far to this biodiversity devastation is unsustainable land-use. This data indicates that land and resource exploitation by the dominion-based global capitalist economy is, in fact, having far more impact on wildlife declines - and on humanity - than climate change is presently. As quantum physics Ph.D. Will Marshall argues, “Climate is missing the point. We have an ecosystem emergency.”

The Dominance of Dominion

“people inevitably misunderstand the present when they live in ignorance of the past... the future of democracy depends upon the past, which is always at work in the present”

- John Keane The Life and Death of Democracy

To understand the origins of this "ecosystem emergency" we need to understand the "dominion" worldview of capitalism. A worldview can be seen as a kind of self-replicating societal mind-virus or meme perpetuating and spreading its reality and manner of seeing the world. The scientific theory of memetics helps explain the power of such memes to spread a set of ideas throughout society. As Alnoor Ladha and Martin Kirk explain, memetics is increasingly validated by various branches of science, including evolutionary theory, quantum physics, cognitive linguistics, and epigenetics.

The dominion worldview of the current global capitalist system is based on an inherently racist and patriarchal meme inherited from the bible. In this meme, God (usually depicted as an old white guy) grants Adam (a younger white guy) "dominion" over the earth and all of nature to “control and shape it.” (God: Genesis 1:26) This meme spread was globally through the enlightenment and places both nature and non-European people (or poor people in general) as inferior beings in a hierarchical construct called the “chain of being."

The logic of the capitalist system sees eternal growth and control of nature and humanity as the primary motives within a game played by rational self-serving players. However, this dominion meme underpinning capitalism is ultimately predicated on the absolute rationality and morality of the cannibalistic consumption of both natural resources and human energy. This worldview ultimately leads to a narrowly materialist and reductionist vision of "human progress" that ignores the inherent importance of human and ecological diversity and interconnection with nature.

This mind-virus of the capitalist project has proven so infectious that it has spread its absolute dominion over the entire planet to achieve near-absolute hegemony and catastrophic consequences for the ecosystem and indigenous peoples. As Ladha and Kirk state "in order for Christianity to become dominant, the existing pagan belief-system, with its understanding of humanity’s place within rather than above nature, had to be all but annihilated."

Over the latter half of the 20th and early 21st centuries, the global economy has orchestrated an unprecedented acceleration of the destruction of nature in its quest for eternal growth from ever-dwindling resources. This is simply because the rules of its operating system depend on this expansion and consumption of new territories and natural and human resources for its continued existence. However, as Ladha and Kirk outline, the exponential nature of the World Bank's 3% global GDP growth imperative to avoid recession, means we now need over US2 trillion in growth every year "just so the entire house of cards doesn’t crumble."

The ever-higher levels of consumption of the commons needed to provide grist for this mill, has also given rise to an increase in authoritarianism and an associated chilling of the freedom of the press and human rights globally. A fierce suppression of whistleblowers, inconvenient journalists, and activists, all but ignored by the mainstream media has effectively ended the accountability of governments and businesses for this human and ecosystem devastation.

Meanwhile, the propaganda arm of this capitalist mind-virus has entered a golden age by taking advantage of the unregulated social media frontier and the breakdown of real journalism. In this new environment, the use of memes as warfare to control, manipulate and misinform the populace to perpetuate and spread the dominion mindset has been perfected.

What is the end game of this dominion worldview? It appears to be incapable of stopping anywhere short of the destruction of all life on Earth. As Nafeez Ahmed defines it:

“This is a life-destroying paradigm, a death-machine whose internal logic culminates in its own termination. It is a matrix of interlocking beliefs, values, behaviours and organisational forms which functions as a barrier, not an entry-point, to life, nature and reality.”

The First Great Extermination

What is the Rojava Revolution? | Accidental Anarchist“The future of the extraordinary feminist and democratic revolution in Rojava is now in danger. The US has announced it will withdraw its military forces from Syria, with whom the Kurdish forces have been fighting against ISIS. This will be a green light for Erdogan’s Turkey to fulfill its threats to attack Rojava and eradicate its nascent democracy. There’s never been a more important time to support Rojava. This clip from Accidental Anarchist shows why it matters.” - Carne Ross

Watch the full movie: filmsforaction.org/watch/accidental-anarchist/

Posted by Films For Action on Saturday, 22 December 2018

“This Is Not the Sixth Extinction. It’s the First Extermination Event. What we are witnessing is not a passive geological event but extermination by capitalism."

Justin McBrien

This increasingly aggressive search of capitalism for new territories and untapped resources has placed increasing pressure on ecosystems across the globe in what Justin McBrien terms the First Extermination Event. As McBrien says, "the great historical struggle against this extermination has been, and remains, the struggle for land and the rights of the commons."

Developing nations and indigenous people are at the forefront of this struggle as the commons in the global south have increasingly come under pressure from privatisation. Indigenous nations account for less than 5 percent of the global population, but are protecting 80 percent of its biodiversity. This ecological wealth is largely in the form of commonly held ecosystems such as forests, oceans, wetlands, and other wildernesses that are crucial reservoirs of biodiversity and buffers against climate change.

Indigenous peoples and developing nations are also suffering disproportionate losses due to an increased reliance on and interconnection with the natural world. Many have already faced, or now face Cultural Extinction due to the fact that their languages, stories, religions, and customs are inextricably interconnected with the ecosystems being destroyed. Nowhere is this process more evident than in the Amazon, where Guardians such as Paulino Paulo Guajajara (above) are being killed for defending their ancestral lands from deforestation.

Due to indebtedness and years of extractive imperialism and capitalism, these nations have minimal ability alone to resist the destruction of these commons or to fund mitigation or adaptation measures. However, they also hold the key to our survival. Unless we are prepared to aggressively challenge this destruction of the remaining commons in the developed world, our chances of preserving biodiversity and a habitable climate on this planet are slim.

Ah… About That “Hope”?

“Hopelessness isn’t natural. It needs to be produced.” - David Graeber

Hope and belief in a better future is an important and subversive act of defiance against the possibility-limiting paradigm of this dominant worldview. In such concerning times, it is all too easy to fall into the trap of “learned hopelessness.” However, as anthropologist David Graeber states in a recent “Tactical Briefing,” to make sense of the seeming impasse of our current situation we must realise that this feeling is the product of:

“a vast bureaucratic apparatus for the creation and maintenance of hopelessness, a kind of giant machine that is designed, first and foremost, to destroy any sense of possible alternative futures.”

So where is one to find hope in the face of this death machine?

There are plenty of indications the people have finally had enough of this worldview driving life on the planet towards extinction. Worldwide uprisings of Extinction Rebellion, the Youth Climate Marches, or other little-publicised uprisings in Ecuador, Iraq, Algeria or Lebanon are all evidence of a desire for a more equal and sustainable world. Perhaps most significant are the protests raging in Chile - the birthplace, most extreme testing ground, and now death ground? of the neoliberal project.

However, past uprisings teach us that in order to ensure this distributed energy succeeds in bringing about lasting change, we require a clear shared vision of the future world we seek to create. The emergent cooperatism worldview gaining traction worldwide provides such a potential framework for the more “life-affirming” future these many groups are seeking to create.

Hope In Common

"Every time a civilization is in crisis, there is a return of the commons"

Michel Bauwens

The current crisis can be seen as stemming from the failure of the dominion worldview and the increasingly strained institutions of the capitalist system to protect our environmental and social commons. One result has been a global resurgence of interest in the commons. This resurgence is underpinned by the cooperatism worldview which stands in direct contradiction to the assumptions of the dominion paradigm of global capitalism.

As Michel Bauwens of the P2P Foundation summarises, “The commons are three things at the same time: a resource (shared), a community (which maintains them) and precise principles of autonomous governance (to regulate them).” This complex and inherently cooperatist nature makes the commons a powerful and popular organising system for managing natural resources and ecosystems amongst people across the world.

This broad-based nature of the commons increases human agency by redistributing power and control over land-use decisions and favouring direct, participatory decision-making by the greatest number of people affected. The bottom-up and decentralised nature of the cooperatism worldview enables solutions and responses to environmental challenges to emerge from those most intricately familiar with particular ecosystems.

This upsurge in the ground-up approach to land-use is evident in the many distributed, local-level collaborative initiatives taking on the guardianship and sustainable use of common lands and resources. In NZ examples include the landscape-scale community conservation literally in my own backyard in Miramar, the self-governance of Te Urewera or the granting of legal rights to the Whanganui river. Ellen Rykers’ recent article on The Dig explores the potential of the Community-centred to biodiversity action in Aotearoa.

More ambitious commons-based approaches abroad include commons fisheries management in Kenya or Nepal’s Community-owned native forests or a plethora of tea, coffee and cacao cooperatives across the developing world. Then there is the astounding (ZAD) "Zone a Defender" - an occupied autonomous zone near Nantes, France (pictured above). Here occupiers have been conserving the forests and wetlands, collectively farming the commons and with community support, resisting forcible eviction by the police for decades.

There are many other examples of the cooperatism approach emerging to create a parallel economy of self-governing alternatives alongside the global capitalist system. These range from small neighbourhood cooperatives and Community Land Trusts to large-scale anti-capitalist experiments like the autonomous indigenous communities of Chiapas, Mexico’s indigenous Zapatista movement.

Such alternatives also include the occupied factories in Paraguay, Argentina or the USA, and autonomous institutes in Korea or the cooperatives, self-governed city areas, and free medical care centres formed in Greece after the recent political and economic crisis. As David Graeber says, such forms of mutual aid associations “spring up pretty much anywhere that state power and global capital seem to be temporarily looking the other way.”

Perhaps most inspiring of all is the success of Rojava, a self-governing, non-denominational and non-patriarchal, autonomous Kurdish region amidst the chaos of Syria. Sadly, this revolutionary "democratic confederalist" project is currently being crushed by surrounding authoritarian powers clearly threatened by the precedent it sets.

Bringing Out The Best In Humans

A commons-based or cooperatist approach to organising society, offers a more rational and scientifically sound way to relate to natural resources than the top-down and growth-based imperatives of the dominion worldview.

The standard argument for the application of a dominion approach to land and resources is Garrett Hardin’s theory of “The Tragedy of the Commons.” However, Elinor Ostrom’s worldwide Nobel Economics prize-winningstudy of “common-pool resource” (CPR) groups in the ‘90s, debunked this idea entirely. Ostrom concluded that groups are capable of avoiding the tragedy of the commons without requiring top-down regulation, as long as certain “core-design conditions” are met.

Even that champion of neoliberal economic theory, The Economist is now on board. The September 2019 issue featured the article:“The alternatives to privatization and nationalization: More public resources could be managed as commons without much loss of efficiency.” The author cites Ostrom’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, in which she called on policymakers to “facilitate the development of institutions that bring out the best in humans.”

However, the fact is, a thermodynamics perspective actually demonstrates the commons approach is MORE energy efficient than standard methods. A research project led by the P2P Foundation on the thermodynamic efficiencies of peer production found that a transition to open and shared models can result in an 80% saving in the amount of matter and energy used in running our society.

Hope From The Edge of the World

“The kin networks that bind people with other living systems resonate with the science

of complex networks, key to understanding many ‘wicked problems’ of our time..."

Dame Anne Salmond, Gary Brierly and Dan Hikuroa.

Let the Rivers Speak: thinking about waterways in Aotearoa New Zealand

We can also take much inspiration from those indigenous people acting as guardians of the natural world against extermination where states and institutions have failed to do so. Examples such as the Guardians of the Amazon, Mauna Kea or Ihumātao represent a refusal to accept the arrogant and materialist dismissal by the dominion paradigm of ancient indigenous knowledge and locally-derived wisdom, democracy and sustainability.

Understanding the worldviews of indigenous societies offers important shifts in perspective, consciousness, and behaviour that global society needs to make urgently in order to have any chance of surviving the coming wave of ecological and social disruption. These worldviews are imbued with a deep understanding of cooperatism and shaped by long histories of using the commons as an approach to land-use and social organisation.

Growing understanding in anthropology and archeology and the science of complex networks confirms the validity of the fundamental tenets of indigenous worldviews: 1. that cooperation is what defines us evolutionarily as a species (Graeber), and 2. that humanity and nature are inextricably interconnected (Salmond et al). Veronika Meduna previously discussed these concepts in relation to Mātauranga Māori in her article on The Dig: Kaitiakitanga: Seeing Nature as your Elder.

We are not, as the dominion worldview of capitalism holds, hierarchical and self-serving beings governed by a “selfish gene.” For most of our history, humans have existed in a mode of cooperation and relational interconnectedness with each other and the natural world. We must all urgently remember and recreate this way of being.

Changing Our Minds

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

George Bernard Shaw

Widespread adoption of a worldview grounded in Cooperatism is the fastest way to get public support for an overhaul of our approach to land-use and rapidly regenerate ecosystems. However, this is easier said than done. The theory of ‘cognitive dissonance’, holds that when reality falsifies our deepest beliefs, we’d rather tinker with the nature of our reality than update our worldview. This accounts for the growing tribalism of populist politics and the susceptibility to disinformation and narrative control that holds the status quo in place.

Cognitive dissonance means that changing minds regarding the environment and our insane economic paradigm will not be done by using facts, statistics or rational debate to convince people of the merits of such an approach. Rather, as Maarten Van Doorn outlines, “Ideas change the world by upgrading people’s ‘normal’... by showing people what is possible, and changing their views about what is socially acceptable.”

In short - the most effective way to change minds is to actually build the world (and worldview) of the commons all around us, making it the new normal as ordinary people rub up against it in their everyday life. Ensuring as many people as possible are able to participate in or benefit from commons-based and ground-up initiatives is one of the most powerful solutions there is to have an impact on the current crisis.

A Global New Deal For The Commons

Launch your meme boldly and see if it will replicate—just like genes replicate, and infect, and move into the organism of society... I believe these memes are the key to societal evolution. But unless the memes are released to play the game, there is no progress.

~ Terrence McKenna

To have any chance of being adopted en masse, proposals for environmental action must directly benefit everyone, but especially disadvantaged communities in most need - migrants, working-class communities and developing nations. As Naomi Klein argues on The Intercept (and in her new book), if we do not link the intersecting climate, migration and social justice crises together into a holistic response, we will face a popular backlash. Klein's astute hypothesis is that “only a Green New Deal can douse the fires of eco-fascism.”

However, proposals for a Green New Deal and other green-growth based approaches such as New Zealand's Zero Carbon Act, simply do not go far enough. They fail to effectively challenge the core extractivist and dominion assumptions of the paradigm that has created the biodiversity crisis. Such approaches miss the point entirely unless they ensure that the basic needs of people and planet are met. The neglect of these core needs for so long by the establishment is the breeding ground for both the increased susceptibility to fascist and authoritarian memes and environmental catastrophe.

There is an existing proposal and petition for a Global Deal for Nature, which I fully support and recommend. However, due to the importance of language and memes to changing worldviews, I still wish to launch this slightly different framing.

So allow me to launch my meme: A Global New Deal For The Commons:

I propose that what humanity and the planet desperately needs is a Global New Deal For The Commons. Such a deal would require a global mobilisation to ensure that the natural and cultural commons are protected and sustainable biodiversity-friendly and cooperatist land-use is adopted. If structured right, such a deal would have a massive impact towards restoring the planetary ecosystem and biodiversity, as well as healing deprived and hopeless communities everywhere in the process.

To truly turn the biodiversity and climate crises around, this new deal needs to happen at least on a scale of wartime efforts such as the Marshall Plan of WWII or the New Deal of the Depression-era. As Rutger Bregman argues, centralised state action will be essential to any realistic efforts to drive an environmental effort on the scale required. However, I am less cynical than Bregman about the power of bottom-up efforts, and believe a properly balanced combination of the two is essential.

A biodiversity-focused investment on this scale could combine central investment with an approach focused on catalysing, fostering, and scaling bottom-up land-use initiatives and ideas. It could prioritise local communities as workforces and support the emergence of ground-up, decentralised solutions and initiatives over centrally imposed or market-based solutions wherever possible.

Such a new deal for the commons would require associated work on reforming land tenure and local democratic and economic institutions on a scale not attempted since the communist project. However, rather than the top-down command and control approach of communism, it would provide a framework, resources and tools for communities to re-learn how to live harmoniously with each other and with nature’s abundance. This approach could spread knowledge, technology and best practice for environmental restoration globally through open sourcing IP and implementing solidarity networks or networks of mutual aid across society.

This new deal would also require real action on the national and global level to reform global governance and regulation and build a more just international order and institutions. This would require new agreements such as an international law of “ecocide,” and strengthened international environmental laws and enforcement mechanisms to ensure the compliance of corporations and rogue imperialist nations. This new order would also need to address debt-enslavement, eternal growth imperatives, and rebalance global wealth disparity to stop wealthy nations from shifting the impacts of growth onto vulnerable populations and ecosystems.

However, crucially, to bring about this new order, we must find ways to continue challenging the narrow confines of permitted thought and debate keeping us locked in the destructive dominion paradigm. It would need to restore the rule of law and ensure the protection of whistleblowers, journalists, activists and politicians challenging this narrative. If not, who will hold power accountable for their inaction or blocking of real progress? Who will continue to tell the stories and defend the rights of those on the margins building the alternative futures discussed above?

The debate around Te Koiroa o Te Koiora, and the to-be-finalised national biodiversity strategy and policy provide an excellent opportunity for New Zealand to lead the way in protecting and restoring the commons with such a new deal. There are good indications that a more community-focused approach is being considered and that more radical proposals resonated well with the public in our recent HiveMind engagement. However, we must ensure that translating this into real progress to fund and support ground-up and cooperatist environmental initiatives is seen as a priority for the Government.

Please indicate if you agree with this statement of hope and declaration of intent here. You can also add your own statements for others to vote on if you wish:

If Window not displaying please follow Link to Pol.is page: https://pol.is/6kwfjtyxhk

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land

Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death? Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing

Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing Gordon Campbell: On Aussie Election Aftershocks And Life Lessons

Gordon Campbell: On Aussie Election Aftershocks And Life Lessons