New Zealand's well-being approach to budget is not new, but could shift major issues

Finance minister Grant Robertson

will announce New Zealand’s first budget that uses a

well-being measures.

from

www.shutterstock.com, CC

BY-ND

Arthur Grimes, Victoria University of Wellington

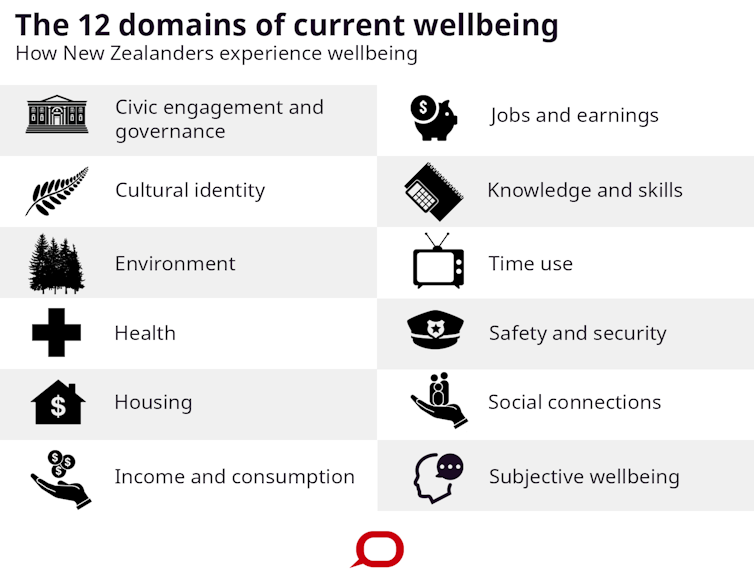

At the end of this month, New Zealand will release its first “Well-being Budget”. It builds on treasury’s Living Standards Framework (LSF), published last December, which introduced a suite of well-being measures, including cultural identity, environment, housing, income and consumption, and social connections.

To help interpret what this might mean for policy, I look at how well-being has been used as a guide for policy elsewhere.

Let’s first look at some prime ministerial words:

Wealth is about so much more than […] dollars can ever measure. It’s time we admitted that there’s more to life than money, and it’s time we focused not just on GDP, but on GWB - general well-being.

And some words from treasury:

The ultimate value of the well-being framework is that it improves the quality of Treasury’s policy advice to government, through helping to identify the important trade-offs for well-being, and providing a consistent basis for understanding their impact.

Read more:

It's

time to vote for happiness and well-being, not mere economic

growth. Here's why:

The eagle-eyed will have noticed some words left out of the first quotation. They are “pounds, or euros or”. The quotation is from UK prime minister David Cameron, in 2006. The second is from the Australian Treasury in 2004, prepared during the Howard government. Its framework built on an Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) publication in 2001.

In introducing the LSF, the New Zealand Treasury stated:

There is more to well-being than just a healthy economy. That’s why the Treasury has developed its Living Standards Framework (LSF) – it helps us advise governments about how the policy trade-offs they make are likely to affect everyone’s living standards.

This is an amalgam of the Cameron speech and the Australian Treasury approach of the mid-2000s. Is there anything new in the New Zealand government’s approach that conservative governments in the UK and Australia had not already considered over a decade ago?

International well-being initiatives

There was another well-being initiative in France, based on the highly publicised Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi (SSF) report in 2009. That report, headed by Jean-Paul Fitoussi and Nobel laureates Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen, was commissioned by French president Nicholas Sarkozy – again a conservative on the political spectrum. It recommended monitoring a broad list of indicators of well-being and sustainability to guide policy.

The UK well-being initiative died as a policy framework with the demise of David Cameron. But the Office of National Statistics has kept the UK’s well-being indicator framework alive. The Australian initiative was maintained by its treasury to inform policy considerations, but it never made it to the frontline of political debate.

The French framework is alive and well. A 2015 budget law requires the French government to report the evolution of new wealth indicators and to assess major reforms. Similar frameworks have been formally adopted as a basis for policy in several other countries.

New Zealand’s approach to well-being

The New Zealand approach is far from new, but it has some distinctive features. Most obviously, it addresses the well-being of New Zealanders rather than people elsewhere. The parallel Stats NZ well-being indicator framework, Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand (IANZ), includes a selection of measures of how New Zealand interacts with the well-being of the rest of the world.

The LSF bears close similarities to the OECD’s Better Life Index. The LSF dashboard comprises 38 indicators across 12 well-being “domains” and measurements of inequalities across different population groups for nine of those domains.

Shutterstock/The

Conversation

Perhaps the most valuable contribution of the LSF has been to highlight differential aspects of well-being across population groups. For instance, on average, Māori perform more poorly compared to the rest of the population on almost every well-being domain. While we suspected this before, some other interesting findings emerge.

Take age, for instance. Treasury shows that while older people’s health is likely to be poorer than average (which is not surprising) they do better, on average, than the rest of the population on most other measures, including material well-being such as income, consumption and housing. Most do not require extra help from government, and they do not need the cash handout that was misleadingly labelled the “winter energy payment”.

How best to use well-being data

Most of the indicators included in both the LSF and IANZ already exist and have long been published by Stats New Zealand. My treasured 1903 (paper) copy of the New Zealand Official Yearbook contains over 750 pages of measures relating, inter alia, to well-being. For instance, it reports that there were 20 “lunatics” per 10,000 population in 1874, which rose to 34 by 1901, and that the proportion was higher among males than females.

For policy purposes, it’s not just what we measure but how we use it. While the treasury’s LSF follows a tried and true course internationally, its use has the potential to be novel. In his budget policy statement, finance minister Grant Robertson listed five priority areas for the “well-being budget”:

transitioning to a sustainable and low-emissions economy

boosting innovation, and social and economic opportunities in a digital age

lifting Māori and Pacific incomes, skills and opportunities

reducing child poverty, improving child well-being and addressing family violence

supporting mental well-being, with a special focus on under 24-year-olds.

It’s not clear how the minister arrived at these five priorities, but prioritisation in fiscal policy is a virtue. The last National government went through a similar exercise with its Better Public Services targets that aimed to reduce long-term welfare dependence, support vulnerable children, boost skills and employment and reduce crime.

The current government has insisted that “budget bids” by public sector agencies align with the five priorities. Even defence expenditures have been analysed as contributors to societal well-being. While we shouldn’t stretch the well-being policy framework too hard (or it may become a nonsense), the stated approach could see real progress in addressing issues at the heart of these priority areas.

The acid tests

There are two key tests. The first is whether the 2019 Well-being Budget provides meaningful fillips to the five priority areas. Ignoring the opaque way in which these priorities were derived, the process will have paid dividends if it succeeds in focusing policy attention on key areas requiring social and economic policy. For too long, budgets have spread largesse thinly over many policy areas, achieving little in any of them.

The second test is whether resources are freed up for the five priority areas by cutting poorly performing programs. The winter energy payment is one example. Interest-free loans to students from wealthy families is another.

A true

well-being budget will target public programs and resources

to where they have the greatest bang-for-buck and will cease

support for programs that have low well-being payoffs. I

expect a moderate pass mark for the first test, but will be

(pleasantly) surprised if I see a pass mark for the

second.![]()

Arthur Grimes, Professor of Wellbeing and Public Policy, Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ian Powell: Gisborne Hospital Senior Doctors Strike Highlights Important Health System Issues

Ian Powell: Gisborne Hospital Senior Doctors Strike Highlights Important Health System Issues Keith Rankin: Who, Neither Politician Nor Monarch, Executed 100,000 Civilians In A Single Night?

Keith Rankin: Who, Neither Politician Nor Monarch, Executed 100,000 Civilians In A Single Night? Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight

Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine

Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor

Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor