History teachers decry 'shameful' ignorance of colonial, Māori history

John Gerritsen, Education Correspondent

In the lead-up to Waitangi Day, history teachers are calling for compulsory teaching of New Zealand's Māori and colonial history in schools, but government representatives are rejecting the idea.

The petition states that "too few New Zealanders have a sound understanding of what brought the Crown and Māori together in the 1840 Treaty". Photo: RNZ / Rebekah Parsons-King

The chairperson of the History Teachers' Association, Graeme Ball, said the number of people who learned about New Zealand's history was shameful and the association had launched a petition to change that.

The petition called on Parliament to pass a law to "make compulsory the coherent teaching of our own past across appropriate year levels in our schools".

"Too few New Zealanders have a sound understanding of what brought the Crown and Māori together in the 1840 Treaty, or of how the relationship played out over the following decades.

"We believe it is a basic right of all to learn this at school (primary and/or secondary) and that students should be exposed to multiple perspectives and be enabled to draw their own conclusions from the evidence presented in line with good historical practice," the petition said.

Mr Ball said the school curriculum set out what skills students should learn, but did not require schools to teach particular topics.

He said that meant it was a complete lottery whether children studied New Zealand's history.

"I tell my classes at the beginning of the year, Year 13 class, that they're going to be an elite, and I say it's really sad that you're going to be an elite because you're going to be a very small percentage of the New Zealanders who actually know something about your country's own history. That's shameful," he said.

Mr Ball said when students did learn about colonial history and the Treaty of Waitangi, their coverage was often cursory.

"Sometimes in Year 9 or 10 at our particular school when we start to talk about the Treaty or something they'll be 'oh we've done it, we know it'. You dig deeper, they know almost nothing about it."

"It's just incredibly ad hoc."

Mr Ball said topics that should be covered included the decades leading up to the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the Waikato Wars, the Native Lands Act and the prophet movements that resisted government encroachment.

He said some schools did not teach colonial history because there were not enough good resources and because students thought it was boring and teachers were afraid of losing enrolments from their senior history classes.

Mr Ball said the History Teachers' Association had decided to push harder to make the subject compulsory and its stance was in tune with national sentiment.

"Attitudes are changing. I think people are ready for this and it'll probably surprise a lot of people too to know that we don't actually teach our own past in a coherent fashion."

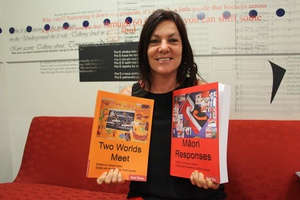

The author of a resource for teaching New Zealand history and a part-time teacher in the University of Auckland's School of Education, Tamsin Hanly, said the topic needed to be taught more widely and more accurately.

Tamsin Hanly holds two

of the

volumes from her teaching resource.

Photo:

RNZ/Dru Faulkner

"It's absolutely vital. Most people in this country, of all ethnicities, have been raised on what's called a standard story, colonial narrative, and it's inaccurate history," she said.

"A lot of teachers are still teaching very inaccurate history if they're teaching at all because a lot of teachers don't go here under the current New Zealand Curriculum that's so generic that you can basically get away with just covering things like Matariki, but you don't have to cover the Land Wars for example."

Ministers reject compulsory curriculum idea

Education Minister Chris Hipkins said schools needed more support to strengthen the teaching of New Zealand history and the Education Ministry was working on a number of projects to address that.

At Waitangi, the Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, told reporters that children should learn about the Treaty of Waitangi.

"I would certainly have an expectation and a hope that it is learnt across our schools," she said.

"This is our country, it is part of our history, it is our founding document as a nation, our students should be learning about it."

But the associate minister of education and minister of Crown Māori relations, Kelvin Davis, was quick to quash any impression the government might make the topic compulsory.

"In terms of the teaching of Te Tiriti in schools, remember that schools are self-governing, self-managing. It's inappropriate for governments to come along and dictate specifics of what's taught in schools," he said.

New Zealand First MP Shane Jones said it was up to schools to decide what they taught but he expected most, if not all, would teach students about the Treaty of Waitangi.

"The reality is that I don't know of a single school that does not offer as a part of social studies or New Zealand history the history and the historical role that the Treaty has played in the evolution of New Zealand," Mr Jones said.

The Education Ministry's deputy secretary early learning and student achievement, Ellen MacGregor-Reid, said the curriculum set strong expectations about what would be taught.

"While we do not set out compulsory lesson plans that all schools must follow, we expect schools and kura to teach Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Māori history and the New Zealand land wars," she said.

Ms MacGregor-Reid said in social sciences students were required to "explore the unique bicultural nature of New Zealand society that derives from the Treaty of Waitangi", and to "learn about past events, experiences, and actions and the changing ways in which these have been interpreted over time".

The president of Te Akatea, the Māori principals' association, Myles Ferris, said most schools taught about the Treaty of Waitangi, but they had a moral obligation to teach New Zealand history correctly.

"There is a lot more to it than just the Treaty and how it was signed. Those underlying factors in most schools are probably under-done," he said.

"Even at primary school level we can teach about social justice, we can teach about the injustices that have happened."

Ian Powell: From Thriving To Surviving - ‘Poster Child’ General Practice Struggle Symbolises Primary Care Crisis

Ian Powell: From Thriving To Surviving - ‘Poster Child’ General Practice Struggle Symbolises Primary Care Crisis Ramzy Baroud: Criminalizing UNRWA - How Israel Is Delegitimizing The United Nations

Ramzy Baroud: Criminalizing UNRWA - How Israel Is Delegitimizing The United Nations Binoy Kampmark: The Price Of Eggs - Why Harris Lost To Trump

Binoy Kampmark: The Price Of Eggs - Why Harris Lost To Trump Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Triumph Of The Swill

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Triumph Of The Swill Gordon Campbell: On US Voter Suppression, Plus The Races To Watch

Gordon Campbell: On US Voter Suppression, Plus The Races To Watch Ian Powell: Fast-Tracking Wealth Accumulation And The War On Nature

Ian Powell: Fast-Tracking Wealth Accumulation And The War On Nature