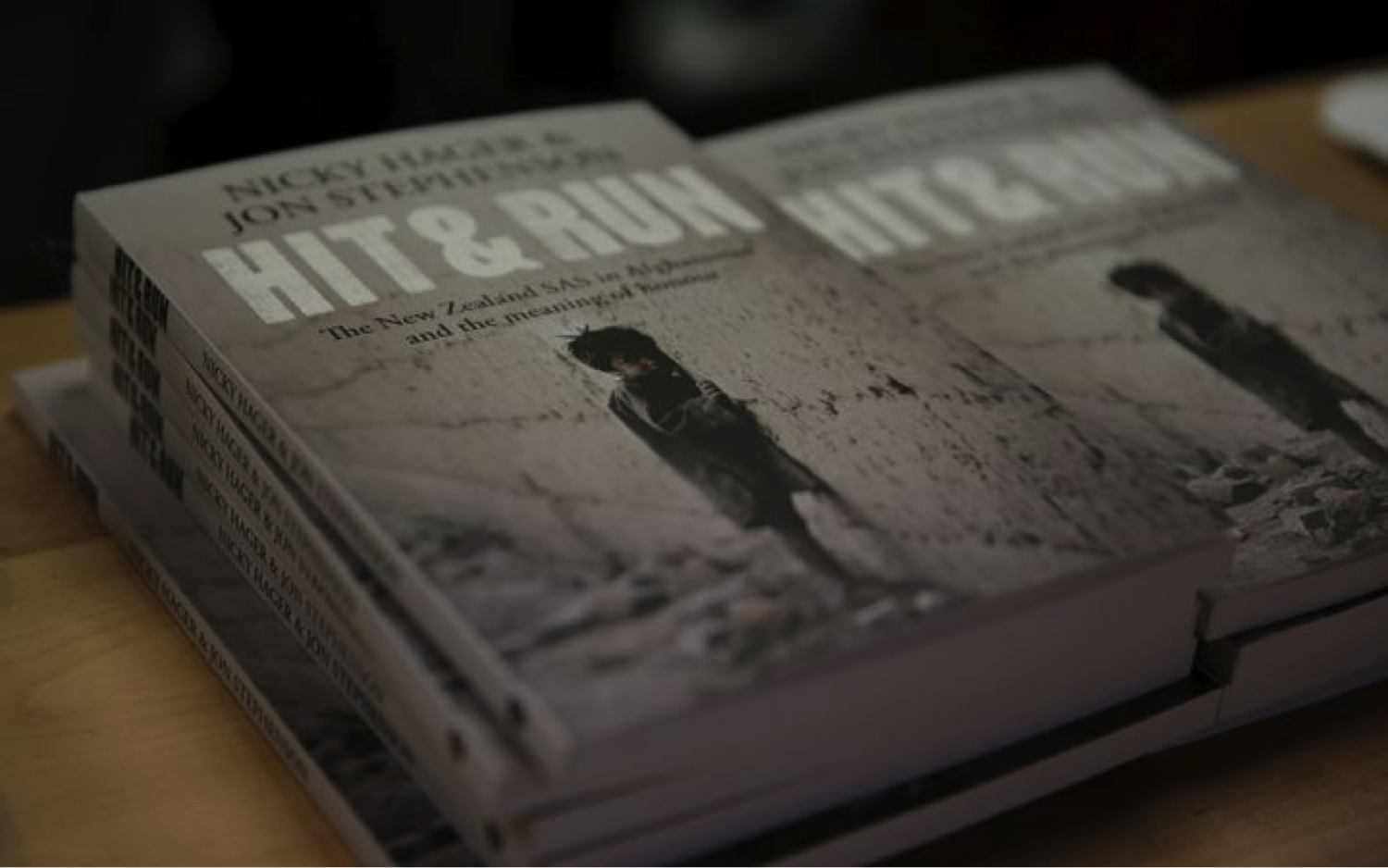

Gordon Campbell on the looming Hit & Run inquiry

It now seems

certain the government will be launching an independent

inquiry (after Easter) into the allegations contained in the

Hit & Run book, and related matters. At the

post-Cabinet press conference this week, PM Jacinda Ardern

confirmed to Werewolf that an

announcement was due “within a week or so.”

The

subsequent exchange went like this:

Campbell: And how would we ensure that the bulk of that material would be open to the public, because the fear would be that all of the issues involved would be declared to be issues of national security. Is there a concern about how that blanket could be removed from the inquiry?

PM: And I think this is one of the reasons that the issue of having an independent person be able to look into this issue was initially raised, because, of course, there will always be some information that we won’t be in a position to put out in the public domain, but having the ability to make sure that we’re still undertaking a proper assessment that the public can have faith in is important. And I think that’s why we originally asked the question, and that’s the kind of issue the Attorney-General’s looking at.

Campbell : And could a special advocate play a role in that context?

PM: Again, these are all questions I want to leave to the Attorney-General to make a final decision on.

The

Background

Since March 2017, there have been

calls for an independent inquiry. The authors of Hit &

Run made the initial case for one. Subsequently, so have

the lawyers who represent the families of the deceased (and

others) in the Afghan villages that were attacked in 2010 by

international forces, including the NZ Defence Force.

In many respects, the NZDF have only themselves to blame for their actions – both in Afghanistan and here at home - that have created a climate where an independent inquiry is now widely seen to be imperative. Initially, NZDF contended that the book had mis-identified the villages concerned.

Yet after the intervention of the Ombudsman, this NZDF claim has been shown to be false :

The book alleged that a 2010 SAS raid on two villages in Afghanistan left six Afghan civilians dead, including a young child, and injured 15 others. The NZDF has always denied the allegations, claiming that insurgents were targeted and that reports of civilian casualties were “unfounded.” Disagreement over the location of the raid was so important to the NZDF’s version of events that it was described as the ‘central premise” of Hit & Run in a media release attributed to Lieutenant General Tim Keating in 2017. Keating said that there were ‘major inaccuracies” in the book with the “ main one” being the location and names of the villages. Readers at home might have assumed that if Hager and Stephenson could not even get the location right, surely the rest of their story collapses.

A year later, the NZDF has quietly conceded that Hager and Stephenson were not inaccurate after all. In official information released without fanfare this month after the Ombudsman intervened, the NZDF has confirmed that photographs of a village published in Hit & Run were indeed the location of the 2010 raid as the authors claimed, although the NZDF continued to quibble about much smaller points such as the distance between two buildings.

Launching an independent inquiry is one thing. Yet it is only a start. Ensuring the inquiry’s deliberations remain as open as possible is the only way of guaranteeing the inquiry will not be a whitewash, carried out largely behind closed doors. With good reason, the public would have no confidence in such an exercise. No doubt, the NZDF will be claiming that national security demands secrecy on almost all the points in contention – especially given that Operation Burnham involved the forces from other countries, who can be presumed to object to information about their activities being exposed to public scrutiny, via a New Zealand inquiry. No doubt, NZDF will argue that future military co-operation could be put in jeopardy if the evidence on Operation Burnham is not handled with the utmost sensitivity.

Attorney-General David Parker will have to deal with these competing interests – openness vs secrecy - when he frames the inquiry’s terms of reference and its protocols. Overseas, there have been many cautionary examples of how badly this balance can be handled. In the UK for instance the Tory government appointed retired judge Sir Peter Gibson in 2011 to conduct an inquiry into Britain’s complicity in the rendition and torture of terrorism suspects. In that inquiry too – which ended up being shelved - serious issues of human rights were said to be at stake. Lip service was given to the matters involved:

David Cameron said [he was] "determined to get to the bottom of what happened" because the reputation of MI5 and MI6 had been overshadowed and the UK's reputation as a country that respects human rights and the rule of law was at risk of being tarnished.

Despite those fine words, the release of the terms of reference and protocols for the Gibson inquiry was greeted with public outrage. Many of the same arguments and concerns that we’re likely to hear about the Operation Burnham inquiry were aired, and for the same good reasons:

Key hearings [would] be held in secret and the cabinet secretary will have the ultimate say over what the public will and will not learn. Individuals subjected to rendition and torture during the so-called war on terror will not be permitted to ask questions of MI5 or MI6 officers and the inquiry will not seek any evidence from foreign intelligence agencies, such as the CIA, about British involvement in the torture and abuse of detainees. The protocol states that the aim is to "establish a reliable account of what happened", but critics point out that it also says the inquiry "will not request evidence from the authorities of other countries.”

These are the kind of questions that need to be asked now about the Operation Burnham inquiry:

• Will the villagers, and their lawyers, be

able to question NZDF and security personnel? If so, will

this be in open session?

• Will the inquiry be

empowered to request relevant evidence from other countries

involved in the actions in question?

• Will the

inquiry’s terms of reference and protocols be required to

adhere to the international law standards that govern

inquiries into serious human rights abuses?

• What

discovery powers will the inquiry have with respect to

NZDF-held material?

• Will a special advocate be

appointed to assess relevant evidence and advise the inquiry

whether national security issues are truly at stake?

No doubt, some genuine matters of national security would be raised by the kind of fearless and wide-ranging inquiry that the events described in Hit & Run plainly demand. The risk is that the national security bogey will be allowed to overwhelm the inquiry, and drive it behind closed doors at every turn. Which will happen, unless the terms of reference and protocols are fashioned in a way that prevents that outcome.

Basically, the public’s confidence in the integrity of its armed forces has to be kept to the fore, as being the paramount interest. The inquiry is not a “best we can manage in the circumstances” exercise whose boundaries can be allowed to be dictated by what NZDF says is necessary for it to maintain its business-as-usual relationships with its allies – especially given that in the case of Operation Burnham, it is those very relationships that have contributed to the abuses that lie at the heart of the inquiry.

In Our Secret Lives

Leonard Cohen was wise about a lot of things…including the consolations of secrecy, and its costs, in our personal and public lives:

Looked through

the paper

Makes you wanna cry

Nobody cares if the

people

Live or die

And the dealer wants you

thinking

That it's either black or white

Thank God

it's not that simple

In my secret life

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death? Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing

Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing Gordon Campbell: On Aussie Election Aftershocks And Life Lessons

Gordon Campbell: On Aussie Election Aftershocks And Life Lessons Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Regarding Popes, Dopes And Hopes

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Regarding Popes, Dopes And Hopes Binoy Kampmark: Fantasy And Exploitation | The US-Ukraine Minerals Deal

Binoy Kampmark: Fantasy And Exploitation | The US-Ukraine Minerals Deal