What Do Those Working with Our Most Vulnerable Neighbours Need From Us to Help Keep Them Safe in a Natural Disaster?

All photo credits Charlotte

Graham.

When you are woken in the night by an earthquake, as thousands of people were in Kaikōura and Wellington just after midnight on 14 November 2016, most probably think first of securing their own safety and the safety of others in their home. For those with children or other vulnerable people in the house, rushing to them is an immediate concern.

But for those who work for non-profits and agencies that support New Zealand’s most vulnerable and marginalised people, it can feel like they’ve got a whole extra family to protect. We’ve all seen the big charities in action after natural disasters, like the Red Cross and the Salvation Army, and those organisations are often key to city or nation-wide relief efforts. But there are much smaller charities - some you won’t ever have heard of - who have built strong bonds, and a level of trust, with people who often have trouble trusting the authorities.

There was some “amazing, unrecognised stuff” happening in Christchurch, where non-profits leapt into the “before the ground even stopped shaking” to protect their vulnerable clients following the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes, said Sharon Torstonson from the Social Wellbeing and Equality Network.

She said the gap between official Civil Defence responses, and completely spontaneous efforts by neighbours to help each other, was filled by “largely invisible” work by the non-profit sector. This puts charities are at special risk after natural disasters, a number in Wellington told me; some had a large number of staff who were parents and who lived in the Hutt City instead of Wellington, due to the capital’s rising house prices. That meant they would need to ensure their children’s safety first in the event of an earthquake, and might be prevented from accessing Wellington city to check on their vulnerable clients if the road into the city is impassable.

Sharon Torstonson from SEWN said that’s a reality cities around the country could be facing when charity sector wages don’t match house prices. In Queenstown, she said, the expensive housing market meant many staff who’d be key to post-disaster infrastructure - especially those who work at the hospital - can’t actually afford to live in Queenstown, and might not be able to reach the resort town “if the Alpine Fault goes.”

As well as with grappling with those concerns, some charities in Wellington said they received no official phone calls or checks after the November 2016 quake, and felt that in a disaster, they and their clients would be left to their own devices. A community-driven plan for Wellington’s CBD is due in 2018, facilitated by the region’s emergency management office.

At least two Wellington charities were forced out of their buildings in the 2016 quake, and both have faced hard journeys, and an unexpected price tag, so they could keep providing the services their clients rely on.

SOMEWHERE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE TO

GO

The youth charity Zeal has been a familiar name in central Wellington for nearly two decades. Now operating in several New Zealand cities, Zeal runs a drop-in space for high school aged youth in the afternoons, holds music events, rents space to young bands to practice, and trains young people with barista skills that will help them get jobs.

The service sounds like a nice-to-have in a disaster situation, but the Facebook page and phone of the centre’s Wellington general manager, Jenna Harris, are bulging with the contacts of young people who might not get a lot of their news from, or have connections with, official and government sources. The drop-in afternoons allow staff at Zeal to build a close rapport with youth who hang out in the central city, some of whom, Harris says, come from homes where they aren’t always safe or cared for. For Civil Defence planners, connecting with Zeal would mean connecting with hundreds of young people who might otherwise be vulnerable.

Zeal Wellington’s general manager, Jenna Harris, in the charity’s new space.

The Wellington centre has had a rough year. Not long before the 2016 quake, they learned when new owners took over their Ghuznee Street building that the centre was at less than 33% of the building code; they’d previously been told the building was rated at 80%. The midnight shakes on 14 November were the last straw, and the charity’s board said Zeal staff could not re-enter the space. Zeal had to pay six months’ rent to break their lease.

Over a period of eight years, Harris said, the space had been given a $300,000 fit-out; it was specific to the building, so that money was lost. As well, the thing that Zeal had always provided: a space that was always there, and during certain hours, always open, for kids to come and hang out after school, was gone in an instant.

Other churches and charities around town were helpful: Zeal held pop-up events, and were given space at Thistle Hall in upper Cuba Street for their drop-in afternoons. But pop-up gigs were much harder to promote when venues were never certain, and each show, Harris said, involved staff schlepping gear around Wellington and to set up from scratch. As well, part of Zeal’s appeal had been its comfortable, welcoming space, and a trestle table and a few chairs, as well as whatever gear could fit in a cardboard box, was not the same. But the centre was determined to keep serving central Wellington’s youth.

Occasionally, possibilities for a new home would pop up, but they always fell through. Zeal couldn’t compete with commercial tenants for Wellington’s incredibly sought-after CBD space, and did not want to move to the suburbs. They knew young people having to pay bus fares to get to Zeal and back would cause a precipitous drop-off in the numbers attending.

Harris says there were no official approaches to find out what they needed, although the Government, during that time, implemented a business recovery package to help businesses affected by the quake to continue to pay their costs, and staff. Harris said she would have applied for such help if she’d known about it and if she’d learned it applied to charities too.

One funder contacted Zeal to ask not how they could help, but rather how the centre would continue to maintain its services at the same level.

After a year when the centre has been unable to advertise its services due to the uncertainty over its space, it’s now found a new home and Harris said young people had kept attending.

She is relieved, but said the charity was still doing it hard financially as the result of losing their building. They’ve made cut-backs; staff doing less extra hours, and reducing the budget for the food they provide to youth at events, “Which is a shame because having lots of food has always been a big part of Zeal,” she said.

“We haven’t even begun to get back on our feet.”

But the charity’s new space in the James Smith building is at the perfect central-city location, and allows the charity to start putting down roots again, and building another safe and comfortable space for youth - preserving the relationships that could be crucial when the next big one hits.

AN APPLE A

DAY

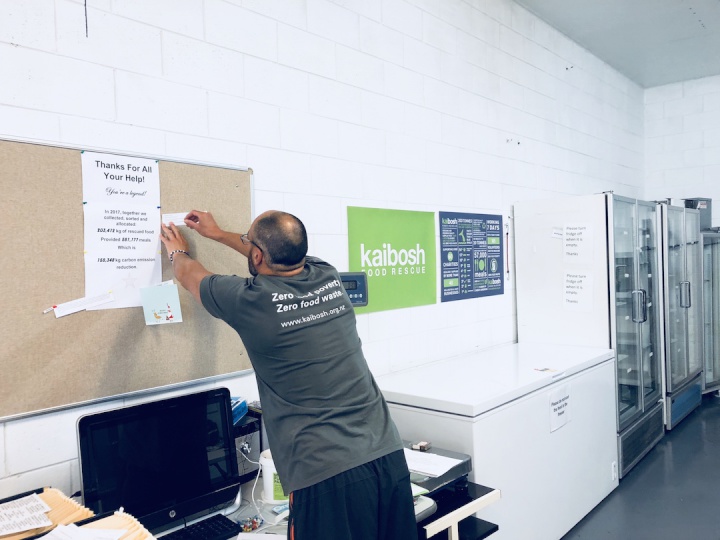

When the food rescue charity Kaibosh was forced out of its building shortly after the November quake - the engineers took one look at the place and literally pulled the alarm - Matt Dagger, who runs the organisation, was mostly gutted that he had leave 350 lettuces rotting on a sorting table.

Kaibosh picks up, sorts, and distributes 25,000 kg of food a month that is perfectly edible but would otherwise be wasted, to 65 social sector organisations that work with the city’s most vulnerable people. They don’t deal with marginalised people directly, but they support those who do, lavishing produce that’s a 70 percent comprised of vegetables, fruit, meat and dairy on people who might otherwise get stuck with tinned tomatoes.

On November 14 2016, some fairly wild security camera footage shows a party in Kaibosh’s empty headquarters on Wellington’s Tennyson Street. The whole building twisted; walls popped out and lights came down.

But the perishable food the charity distributes was still waiting for pickup, and hungry people all over the city, and in Wellington’s shelters and social housing, still needed their produce. Matt Dagger was determined there wouldn’t be a break in service, even after engineers showed up and in a moment of “high drama,” ordered everyone out.

Dagger thought he’d have a new venue for the charity in a few days; instead, staff operated sorting food out of Wellington City Mission’s premises for about six weeks. Kaibosh has two locations at which its volunteers sort food for delivery - one’s in the Hutt - and it had prepared a business continuity plan in case of something like an earthquake. But Dagger said what they hadn’t counted on was the increase in demand: supermarkets had stayed closed and wanted to get rid of their produce. And due to the quakes, the social sector was encountering more need than ever.

Kaibosh General Manager Matt

Dagger

Kaibosh had to be picky. It cut some of its food suppliers from the list, and was not able to keep on all of its charities, but it kept working. Finally, in February 2017, the charity found a temporary, short-term lease on Myrtle Street in Mt. Cook. In moving, Kaibosh lost 30 percent of its volunteers, and the money situation had been tough, Dagger said.

"The financial impact to to us of moving, re-setting up our chillers, hiring staff to do things that volunteers used to do... We took a financial hit," he said.

The charity ran a fundraising campaign and Countdown, one of the organisation’s suppliers, underwrote the move with a cheque for $25,000. The charity wasn’t offered Government help.

Money was still tight, but Dagger said the charity had majorly boosted its efficiency in the past year, and had also attended business continuity workshops run by WREMO that had improved their disaster planning for the future. Kaibosh will have to foot the bill for one more move; its temporary sublet lease is up in early 2018.

Dagger was determined to make it work.

"That's 65 organisations who don't have to buy food, not having to have people going out and acquire it," he said.

"It's massive, massive savings to the whole charitable sector, who can put their resources into providing services."

WHAT CAN THE

GOVERNMENT DO TO HELP THOSE WHO HELP THE VULNERABLE?

Of the many organisations I spoke to in the social sector, there was still a lot of uncertainty about how stronger partnerships between central and local Government and the charity sector could work in the event of a disaster - and what needs to be done in advance.

In Australia, initiatives are underway to bring the charity and government sectors closer. Bridget Tehan is the Senior Policy Analyst Emergency Management at the Victorian Council of Social Service, said there were two major ways the Government could help.

“They can ensure that community organisations are resilient in themselves,” she said. “This should include appropriate insurance, emergency planning and business continuity planning.”

Tehan said the Government also needed to make sure emergency management frameworks recognised and clearly articulated the roles of community sector organisations, and ensured that their service agreements and funding arrangements reflected those roles.

She agreed that funding to undertake such initiatives was “a huge issue,” and that funding models and reporting requirements often prevented organisations from acting on immediate or emerging needs immediately after a crisis.

This was reinforced by people in Christchurch’s social sector, who said their best collaborations with Government to meet the needs of vulnerable clients were those in which the usual reporting requirements and paperwork were temporarily suspended, for trusted organisations, by departments like the Ministry for Social Development.

Tehan said Governments needed to recognise that trust and word of mouth took time to develop - and they should rely on those who had already built such rapport, rather than expecting it to be replicated in a disaster situation.

This story was funded by a grant from the Scoop Foundation for Public Interest Journalism. For more on the ways Civil Defence planners are building rapport with communities, listen to our interview with Daniel Homsey. And to find out more about the challenges facing vulnerable communities in preparing for a disaster, read the story Scoop funded in New Zealand Geographic, out now.

Binoy Kampmark: Closed For Business - The Oddities Of Trump’s Tariffs

Binoy Kampmark: Closed For Business - The Oddities Of Trump’s Tariffs Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Teach Children The Distinction Between The World And Nature

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Teach Children The Distinction Between The World And Nature Ramzy Baroud: Civil War On The Horizon? The Ashkenazi-Sephardic Conflict And Israel’s Future

Ramzy Baroud: Civil War On The Horizon? The Ashkenazi-Sephardic Conflict And Israel’s Future Gordon Campbell: On The Government’s Latest Ferries Scam

Gordon Campbell: On The Government’s Latest Ferries Scam Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - While We're Breaking Up Monoliths, What About MBIE?

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - While We're Breaking Up Monoliths, What About MBIE? Adrian Maidment: Supermarket Signs

Adrian Maidment: Supermarket Signs