The recent Gastro outbreak affecting over

5,000 people in Havelock North is likely to increase the

rate of serious autoimmune diseases among those affected.

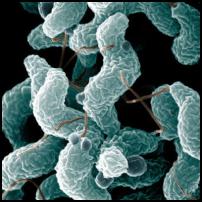

Common inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) Crohn’s disease

and ulcerative colitis have been linked to the bacterial

infection campylobacteriosis that has been identified as the

cause of this outbreak. Onset of these chronic diseases

associated with this widespread infection will seriously

affect the quality of life of the affected individuals and

will place additional costs and burden on the public health

system. It is important that more is done to raise awareness

of this potential correlation and to proactively monitor and

prevent IBD developing in those affected by the outbreak. It

is also important to prevent this type of outbreak from

occurring in the future.

Increased Risk of Bowel Disease

IBD is a category of incurable and debilitating disease that can lead to nutritional deficiencies and lifelong relapsing symptoms. New Zealand has one of the highest rates of IBD worldwide with a recent study led by Professor Richard Gearry of Otago University outlining that the highest rate of Crohn’s disease globally has been reported in the Canterbury region.

There is accumulating evidence of the role of infection with gastrointestinal pathogens such as campylobacter in the development of IBD. Professor Michael Baker, of the Department of Public Health at Otago University, believes there is clear epidemiological evidence of an association between gastroenteritis caused by Campylobacter and other pathogens and IBD. He refers to a Danish population-based cohort study in 2009, which demonstrated that individuals infected with Campylobacter are three times more likely to develop IBD.

It is believed that the initial bacterial infection from pathogens such as Campylobacter leads to increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut lining), which allows the bacteria to enter the bloodstream and triggers the autoimmune process. Professor Baker says that while the natural immune response to such infections is life-saving, it can also lead to systemic inflammatory reactions that can result in serious illness or even fatalities in rare instances.

Professor Baker’s past research has established a strong correlation between Campylobacter infection and the autoimmune disease Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS). However, he is careful to point out that such a clear link has not yet been definitively established between such infections and IBD.

“There is a real association, but causality is harder to pin down in IBD than with these other diseases due to the long timeframe for onset as well as the multiple factors potentially involved such as genetics and environmental triggers.”

A 2013 Otago University study also found an association of this nature between Campylobacter infection and the onset of Crohn’s Disease, concluding “recent Campylobacter infection may be a trigger or contribute to the pathogenesis of CD in some individuals.”

Prevention Better than Cure

What is clear is that once IBD is active, it is very difficult to reverse the immune response and in most cases expensive ongoing immune-suppressive treatment and surgery is required to manage the disease. Many within the medical profession have highlighted the existence of a rapidly worsening epidemic of IBD in New Zealand. This ‘epidemic’ is estimated to cost the taxpayers of New Zealand at least $100 Million annually in real treatment costs according to research from Otago University. This figure does not even take into account the personal economic loss borne by those affected and their families.

Current treatment of severe gastroenteritis caused by bacterial infections such as Campylobacter may include a course of antibiotics, which also presents potential risks. According to Professor Baker, the complex mix of microorganisms in our gut, our microbiome, is still very poorly understood. It is possible that the antibiotics taken to treat infections could even be contributing to the onset of IBD by killing off beneficial bacteria and altering our gut microbiome.

“If our goal to protect people from these infectious diseases we have to do more to keep these pathogens out of our water and food sources. That will also reduce our risk of inflammatory consequences such as IBD, GBS and reactive arthritis,” he says.

A 2014 New Zealand Medical Journal article by Rebekah Lane, Simon Briggs also outlines that antibiotic resistance of campylobacter infections is growing due to the increasing use of antibiotics in the farming industry and concludes that prevention is the best approach.

“Given the very limited benefit of antibiotic treatment and the increasing rates of antibiotic resistance, prevention of campylobacteriosis must be the goal.”

Link to dairy farming

Rates of campylobacteriosis in New Zealand are amongst the highest in the developed world, with the incidence of reported cases increasing steadily since this disease first became notifiable in 1980. A 2012 study also found that intestinal pathogens including Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), adherent-invasive Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter are associated at fairly high prevalence with Crohn's disease. All of these bacterial strains are commonly found in faeces of ruminants (cattle and sheep).

It has been suggested by both the local Council and Environmental Science and Research that the most likely cause of this Havelock North outbreak is faecal pollution from sheep and cattle farming entering the water supply. Mike Joy, a lecturer in environmental science and ecology at Massey University recently told TV3's The Nation the link to intensive farming was clear.

"I'm sure most New Zealanders don't realise that we have the highest rates in the OECD or the developed world of these gastro diseases that come from animals. Central and local government have just allowed this massive expansion of intensification that's caused the problems and done nothing about it."

The problem of IBD appears to have been increasing in line with the intensification of dairy farming over the past few decades. Given the fact that New Zealand has both one of the highest incidences of both gastroenteritis from Campylobacter and other ruminant derived pathogens and the highest rate of IBD worldwide, it is difficult to deny there is a correlation between the two.

What next?

The regional DHB and public health organisations must take further steps to alert all those potentially affected by the Campylobacter outbreak to this increased risk of developing IBD and must assist them to take preventative steps to avoid the disease onset rather than waiting for it to develop. Prevention of IBD requires monitoring gastrointestinal symptoms closely for signs of IBD after resolution of the initial infection for a prolonged period.

Professor Baker believes New Zealand is well placed to conduct more conclusive and systematic research on the effects of Campylobacter infection on IBD. We have the ability to link medical records of all of those infected with Campylobacter so that they can tracked over a defined period. However, performing this type of comprehensive study will require both resources and sustained commitment from researchers and relevant government agencies and health sector organisations.

If there is even a small chance that faecal pollution from farming plays a role in development of these serious diseases then perhaps we should be taking a more precautionary approach to preventing such outbreaks from occurring. The best preventative measure we can take in this regard appears to be keeping infectious pathogens out of our drinking water and food in the first place. This serious public health issue and its human and economic costs therefore appears to be yet another reason for stronger regulation of farming practices and other potentially polluting industries in New Zealand.

Gordon Campbell: On NZ’s Silence Over Gaza, And Creeping Health Privatisation

Gordon Campbell: On NZ’s Silence Over Gaza, And Creeping Health Privatisation Richard S. Ehrlich: Pakistan & China Down 6 Indian Warplanes

Richard S. Ehrlich: Pakistan & China Down 6 Indian Warplanes Keith Rankin: War In Sudan

Keith Rankin: War In Sudan Ramzy Baroud: Netanyahu's Endgame - Isolation And The Shattered Illusion Of Power

Ramzy Baroud: Netanyahu's Endgame - Isolation And The Shattered Illusion Of Power Jeremy Rose: Starvation Of Gaza A Continuation Of A Decades-old Plan

Jeremy Rose: Starvation Of Gaza A Continuation Of A Decades-old Plan Keith Rankin: The Aratere And The New Zealand Main Trunk Line

Keith Rankin: The Aratere And The New Zealand Main Trunk Line