Hunger Strike! Is It Still an Effective Mode of Resistance?

Hunger Strike! Is It Still an Effective Mode of Resistance?

by Pam

Bailey

March 13, 2014

Prisoners are perhaps the most powerless individuals in the world. They are at the mercy of their captors -- deprived of freedom of movement, stripped of virtually all personal resources, limited in communication with the outside to rationed, supervised moments.

But the human spirit is not easily extinguished, and particularly when people are imprisoned for their belief in a cause, the natural leaders among them fight back with what little they have – their brains and their bodies.

“Hunger strikes are very much about power,” says Fran Buntman, a professor of sociology at the United States’ George Washington University and author of a book about Nelson Mandela and his imprisonment on Robben Island. “It's the attempt of powerless people to exert some power over their circumstances, and governments don't like people contesting their power. Part of the point of imprisoning people is to have control over their bodies, and the last thing the administration wants is for the detainees to take that power back.”

As this article was written, individuals held captive around the world were engaged in one of the oldest tactics of resistance – the hunger strike.

In the United States, eight to nine inmates

held at a federal “supermax” prison in Colorado were on

hunger strike and being forcibly fed. Participants were

protesting conditions that include isolation for up to 24

hours a day in concrete “boxcar” cells without access to

even a window.

In Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, 25 prisoners swept

up in the United States’ “war on terror” and held

without charge or trial were refusing food – with 16 of

them being force-fed.

In Vietnam, three activists were on the 25th day of a strike to protest their detention without charge, after they were seized for attempting to investigate a police raid on a fellow dissident’s home.

In Saudi Arabia, two founders of a human rights organization were refusing food to protest harsh conditions. The men have been imprisoned for nearly a year on charges such as “disobeying the ruler” and “inciting disorder.”. In Cairo, Egypt, Abdullah al-Shami, one of four reporters for Al-Jazeera detained by the military regime, had entered his second month on hunger strike. Meanwhile, at least 1,500 other Egyptians held in prison for what they describe as politically motivated reasons announced they were launching their own strikes.

However, the most constant presence among hunger strikers today, no matter when the survey is taken, is the Palestinians. As of this writing, at least six Palestinians held in Israeli jails have been on hunger strike since early to late January. Four are protesting their “administrative detention” – a bureaucratic term for imprisonment without charge or trial, a common practice of the Israeli military. The other two are striking against their solitary confinement, along with medical neglect. The Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association has joined with the World Organization Against Torture, expressing concern about their health and harsh treatment, as well as calling on international activists to contact Israeli authorities in protest.

In

addition, in a leaked letter that made it to the

prisoner support group UFree, a group of Palestinian

detainees from Nafha Prison in southern Israel declared it

will begin a collective strike in the following weeks. The

action, said the letter, is being called both in solidarity

with their six peers and to protest the broken commitments

of the Israel Prison Service (IPS), which had pledged when

the last collective strike ended on May 15, 2012, to improve prison conditions. According to

the Samidoun (Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network)

website, the new demands include:

• Professional and

quick medical treatment.

• Full implementation of the

earlier IPS pledge to allow visits for families from Gaza

every two weeks.

• An end to arbitrary and lengthy

isolation.

• An end to use of a device called the

“Bosta” – an iron chair with shackles -- particularly

for transport of sick prisoners.

Adding further tension is a new rule now under consideration by the Israeli government that would allow the force-feeding of hunger-striking prisoners whose lives are in danger. Israel had previously stopped the practice after three prisoners died as a result. Although the practice of force-feeding has not stopped prisoners from launching hunger strikes in the past, there is no question that the tactic makes them harder to sustain.

Why resort to hunger strike?

Alternative methods for forcing prison administrations are few, but they do exist. Nelson Mandela joined a hunger strike in 1966, two years after he was sent to prison, but later began to question the efficacy of the tactic – favoring instead actions such as work stoppages and “go-slows.” It’s hard to argue that the eventual freedom of South African blacks would have been better served if he had risked death like the Irish in 1981 or had pressed only for his own release. Fellow ANC member Mac Maharaj, who smuggled out the first draft of Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, in 1976, had this to say about the power of his chosen path:

“The warders were caught in this space where on one hand they were meant to fear and hate us 'monsters’, but on the other hand they saw everyone change their behavior when they were talking to Mandela. They saw this black prisoner standing his ground, never shouting or screaming but always keeping his composure while the person taking to him lost his. You could see they were being forced to think about what they had been told about us. From day one, Mandela maintained a kind of dignity that we began to model ourselves on.”

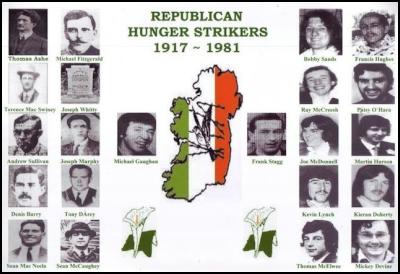

Of course, not everyone can be a Nelson Mandela. And each situation has its own, unique set of challenges. In the case of the Irish, for instance, the hunger strike in which 10 men eventually died came only after five years of just the kind of disobedience Mandela advocated.

Click for big version.

“It started with what we called the ‘blanket protest,” recalls Patrick Sheehan, who lived on only water and salt for 55 days and would surely have been the 11th man to die if the strike had not been called to a halt. Following the British decision to treat members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as common criminals rather than political prisoners (which meant, in part, that they were not allowed to wear their own clothes), several hundred of the imprisoned men refused to cooperate. “The first prisoner to face the new regime was 18-year-old Kieran Nugent who refused to wear the convict uniform. He was stripped naked and thrown into a cell with only a blanket. He wrapped the blanket around himself for warmth and modesty and became a ‘Blanketman.’ As others joined him, and their numbers grew, the attempts to break the prisoners increased. They were prevented from wearing the blanket when they left their cells to wash or to use the toilet or empty their toilet pot. Excrement began to flood their cells and they had to throw the liquid out whenever the doors were opened and spread the solid waste on the walls to try and keep themselves as clean as possible. This was known as the ‘no-wash’ protest.”

When the British refused to budge, however, the prisoners concluded they had to bring the matter to a head – triggering the 1981 hunger strike.

Jonathan Hafetz, an associate professor of law at Seton Hall University School of Law who focuses his work on the prisoners in Guantanmo, wrote recently that, “The reality is that hunger strikes… have an unparalleled ability to focus the world's attention on the ongoing plight of men whose situation is so desperate they would rather starve themselves than go on living in legal limbo.”

While the strike was eventually broken by increasingly harsh conditions, the prisoners achieved a victory first: “Indeed, it was the international media attention on the mass hunger strikes last spring that propelled Guantanamo back onto the public radar, causing President Barack Obama to re-energize his moribund efforts to repatriate prisoners and close the detention center,” observed Haftez.

Addameer agrees, saying that, “Due to Israel’s use of administrative detention, and the lack of due process afforded to Palestinians in the military court system, a hunger strike represents the single-most non-violent tool available to fight for their basic human rights.”

The changing nature of Palestinian prison resistance:

Since Israel seized control of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip in 1967, imprisonment has become a tragic rite of passage for an estimated one in five Palestinians. Today, the Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association reports that 5,023 Palestinians are being held as political prisoners in Israeli jails – including 155 without trial or charge. A report from Israel’s own Justice Ministry documented widespread overcrowding, poor hygienic conditions and “excessive punitive measures” – ranging from extended isolation to severe beatings -- in most facilities.

Faced by these restrictive conditions, hunger strikes are a mainstay of Palestinian prisoners seeking to use what little leverage they have to force change. Repeated collective hunger strikes have been documented beginning in 1968, occurring at least every several years.

However, a trend began building in 2012, in which hunger strikes are increasingly launched by individual prisoners seeking release for themselves, vs. the traditional collective push for improved conditions for all. The pattern began with Khader Adnan, a 33-year-old baker and member of the Islamic Jihad movement. He was arrested without charge in the middle of the night on Dec. 17, 2011, and the following day, Adnan began what at the time was the longest hunger strike in Palestinian history – 66 days. His protest captured the attention of media in the region, inspired solidarity actions both in the West Bank and Gaza, and triggered a rash of other strikes -- culminating in a mass action by an estimated 1,800 other Palestinian prisoners. On Feb, 21, 2012, a deal was announced between Adnan and the Israeli authorities in which they agreed to release him the following April 17. Adnan announced victory and ended his hunger strike.

Since then, a virtual stampede of other prisoners have followed in Adnan’s footsteps, launching their own strikes for individual freedom. Increasingly, however, they are receiving attention only on a few activist websites. And while some have been successful in satisfying at least a few demands, many others have not – depending on how you define a “win.” Hana Shalaby, for instance, ended her 43-day hunger strike not too long after Adnan – by agreeing to be deported to the Gaza Strip for three years, unreachable from her West Bank hometown of Jenin.

Even when demands are granted, Israeli commitments often prove to be unreliable. For example, five Palestinians with Jordanian citizenship held in Israeli jails announced a partial hunger strike in May of 2013. Four of them ended their protest the following August (the fifth followed suit on Dec. 30), citing “lack of international attention” and a promise by the Israelis to at least allow their families to visit. However, that pledge – which only allowed a visit by three family members each, once every two years -- has not yet been honored.

“It must be remembered that Israel has a very poor track record of keeping its side of the agreements,” noted the UK-based group Inminds.com in January. “The families of the (first) four Jordanian hunger strikers still have not had their visitation rights, which Israel agreed to over four months ago. And still, agreement was only for three family members – one visit every two years.”

What is diluting the effects of today’s strikes?

The evolving Palestinian situation has some unique challenges, both imposed and self-induced:

Powerful enemies. The Irish hunger strikers had powerful allies in the United States, due to support groups formed by its large immigrant population. In contrast, one of the strongest American lobbies today (the American-Israeli Political Action Committee, or AIPAC) supports Israeli policy. That lobby is so strong that according to Mourad Jadallah, a researcher and spokesman for Addameer, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry asked Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to refrain from honoring a request from the Higher Council of Administrative Detainees to take their case to the International Criminal Court. And Abbas agreed.

Media fatigue and skepticism. When powerful allies do not exist, media coverage becomes especially important. However, the uncoordinated wave of individual, on-and-off actions by Palestinian prisoners -- with many resorting to additions of glucose, vitamins and even juice or milk when their health begins to wane -- has induced a sense of fatigue among both activists and the media, as well as doubts about the prisoners’ commitment. (This is why some of the later Palestinian protesters have been reported to be on strikes of 100-plus days. Of the Irish strikers, who limited themselves to water and salt, the one who lived the longest lasted just 73 days.)

Amjad Abu Assab, head of a committee that represents prisoners from Jerusalem, explains that collective hunger strikes typically do not extend beyond a month, and thus participants can forego everything but water and salt. However, individual strikers, he says, feel they must consume some extra nutrients in order to last for the long haul – required to build up public attention and support.

“Individual strikes lack media coverage and the people’s support, especially in the beginning,” agrees Akram Rikhawi, who ended his own partial hunger strike of 102 days in the summer of 2012, in return for release six months early.

However, as the most recent individual strikes have illustrated, such “halfway strikes” can backfire – especially when there are so many and some participants simply give up.

“Sadly, a condition for widespread support for hunger strikers is that they must be perceived as willing to pursue the strike to death,” says former Irish prisoner Sheehan. “If prisoners abandon the hunger strike without a settlement, it becomes harder for the next striker to be taken seriously. To be blunt, a person who wishes to start a hunger strike needs to be willing to follow it to its conclusion.”

In fact, in the case of Khader Adnan, the international media didn’t start paying attention until day 61 of his total strike – when the prospect that he might actually die became real.

The book Ten Men Dead explains how the Irish prisoners learned from a failed past attempt, when a group hunger strike was broken by a grieving family member who intervened -- thinking that the loss of one participant wouldn’t make much difference. Bobby Sands, who went on to become the first of the 10 men to die, developed the strategy in which new participants were added one by one, rather like a conveyor belt. He knew that there would be less temptation to quit if a particular prisoner was the only one keeping the strike going.

David Remes, an attorney who gave up a lucrative corporate-law business to specialize in representing Guantanamo detainees, does not believe that prisoners have to literally starve to have an impact, but he does think the action needs to be “sustained, broad-based and well-publicized.”

Limited strategy. A related challenge is the “why” and “for what” behind the hunger strikes. In the case of the individual hunger strikers, the demand is typically one person’s release.

Addameer’s Jadallah says, “Although we understand the motivation behind the individual strikes, we are noticing that they are becoming less effective and believe the strategy needs to be seriously re-examined by the prisoners. There is an ongoing debate among those who work on behalf of prisoners on this subject, but there is general consensus that group strikes with collective demands are the most productive.”

Gerry MacLochlainn, who represented the nationalist Irish party, Sinn Féin, in Great Britain for 14 years, agrees. During his tenure, several ceasefires led to the Good Friday Agreement that ended the armed dispute.

“Demands to release prisoners do not have a great history of success,” he explains, adding that while the Irish prisoners rolled out their strikes one by one, they were planned collectively and focused on group needs. “Basically, the authorities have a number of ways of dealing with such demands. One way is to allow the pressure to build until it reaches a crescendo and then release the prisoner. But then the pressure subsides and has to be built up again for the next prisoner. If a prisoner breaks his or her fast, then the state is off the hook, the campaign deflates again and the state is able to relax until another prisoner reaches the critical point.” And, in fact, that is exactly what has occurred among the Palestinians.

In Bahrain, where a segment of the population also is suffering oppression and inhumane detention, human rights activist Zainab Alkhawaja told Democracy Now that “if the government tries to solve the situation just by releasing some political prisoners, that’s not going to be the real solution. The government must give up some of the power and control that they have. The people of Bahrain want ultimately to have a full democracy.”

Perhaps in the case of the Palestinians, there also are broader goals more important in the long run than individual releases? In addition, perhaps some time should be spent to help cultivate and support leaders among Palestinian prisoners who could lead resistance efforts along the lines of Mandela’s example, through writing and other forms of solidarity actions?

On the other hand, sometimes what seems like individual wins can carry larger symbolism – like the case of Samer Issawi. Over the course of a partial hunger strike of 266 days, Issawi lost half of his body weight and suffered numerous health problems – yet rejected offers to release him, if he agreed to be deported someplace else. His insistence on going home to East Jerusalem, a city being colonized aggressively by Zionist settlers, captured the hearts of activists and caught the fickle media’s attention – and he won.

“My victory was a Palestinian victory that proves nothing is impossible in the face of our will,” he says now. “If I had to do it over again, I would, because nothing is more valuable than freedom.”

Inconsistent coordination and recruitment of support. A challenge related to the stream of on-and-off individual strikes is the difficulty activists face in finding consistent, up-to-date information and sharing a coherent call to action. Information on who is striking, why and their conditions is spread among three websites – Addameer (headquartered in the West Bank), UFree (which operates out of the UK) and Samidoun (which is run out of Canada).

Some of their information is the same, but in other cases it differs. And while a visitor may learn one day that certain individuals are striking, their names will often suddenly disappear in later reports, leaving readers to wonder what happened to them.

And while Khaled Waleed, operations coordinator for UFree says the three organizations communicate with each other, their public faces are separate and disparate, often achieving a level of awareness only among hard-core activists.

Inter-party conflict. A related challenge is lack of coordination and cooperation among Palestinian political parties. Waleed notes that many of the individual strikers are independent or from the Islamic Jihad movement, which is not as organized and thus is weaker than Fatah and Hamas. Therefore, the prisoners feel the need to “go it alone.” Due to the current divisiveness among Palestinian factions – a fact due in no small part to Israeli manipulation both inside the prisons and out – today’s hunger strikes are not as strong as they could be, Waleed believes.

“The trust and comradeship between the external and prison leadership, made it very difficult for the British to divide the prisoners,” agrees former Irish hunger striker Sheehan. “This unity and co-ordination was crucial.”

These are difficult, intractable issues. No one wants to tell individuals facing years in prison under harsh conditions to not do everything possible for their freedom – or to be prepared to starve themselves to death. And the political divisions among Palestinians have festered for years.

Yet in light of the fitful progress of the negotiations for peace (if one could call it progress at all), the number of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails will only continue to grow, and with it, their ill treatment. It’s time, says Waleed, for oppressed populations and their supporters to re-examine resistance past and present, learning from what has worked and what hasn’t. And Palestinians would be among the first to benefit.

Pam Bailey is a freelance writer who specializes in the human impact of governmental policies, and the attempt of civil society to push back. Based in the United States, she has traveled extensively to Israel, the occupied Palestinian Territories, Yemen and Pakistan -- focusing on issues ranging from U.S. drone attacks, to Israeli control of Gaza, to the ongoing detention of prisoners in Guantanamo. Pam has published for news operations such as InterPress Service, Truthout, Al Jazeera and Mondoweiss. http://paminprogress.tumblr.com

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Regarding Popes, Dopes And Hopes

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Regarding Popes, Dopes And Hopes Binoy Kampmark: Fantasy And Exploitation | The US-Ukraine Minerals Deal

Binoy Kampmark: Fantasy And Exploitation | The US-Ukraine Minerals Deal Gordon Campbell: On The Aussie Election Finale

Gordon Campbell: On The Aussie Election Finale Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Enlightenment Is Dead; What Is True Enlightenment?

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: The Enlightenment Is Dead; What Is True Enlightenment? Ian Powell: Widening Gap Between Health System Leadership And Health Workforce

Ian Powell: Widening Gap Between Health System Leadership And Health Workforce Keith Rankin: The Great World War 1914-1945 - Germany, Russia, Ukraine

Keith Rankin: The Great World War 1914-1945 - Germany, Russia, Ukraine