One Direction, Justin Bieber and female sexuality

One Direction, Justin Bieber and female sexuality

by Anne Russell

April 27,

2012

I left work at around 5.30pm on Monday, and walked down Lambton Quay and along Grey St, passing the InterContinental Hotel. A bunch of teenage girls, long-legged in school uniforms, were clustered around the entrance behind barriers, squealing intermittently. I knew they must be waiting for boy band One Direction, who recently played a concert at the St James (apparently you could hear the screams in Brooklyn and Mt Cook). I tapped a girl on the shoulder and asked when they were meant to be coming out. “Well, their plane's at 8 o'clock, so it has to be some time before them. That's their room up there, see,” she said, pointing to an open window. I bumped into a friend, and we settled back to watch the spectacle.

Had I known I would end up hanging around so long I would've gone home. The girls raised false alarm after false alarm—screaming would escalate when anyone walked out of the building and died down just as quickly. Periodically the crowd chanted for the band to come out, or sang perfectly inflected song lyrics in unison. “What do we want? One Direction! When do we want it? Now!” chorused the girls at top volume. “Stand up, fight back!” said my friend, waving her fist, and we both laughed.

After an hour and a half, the band finally came out of the hotel. I was up a lamp-post at the time, a good vantage point, and held on tight as the crowd rushed past me to take photos. The whole thing lasted about a minute, leaving throngs of teenage girls screaming and sobbing in the parking bay. I walked to the bus stop, and watched a small group go past. “Harry looked RIGHT INTO MY EYES,” said one girl, hand on heart, eyes wide. “It feels like a dream,” breathed another. They got on my bus a few minutes later and sat in front of me, still rhapsodising about Harry's good looks. One girl passed her friend a water bottle, and opened the window to help cool the flush on their cheeks.

Screaming outside the hotel. Video credit to Stella Blake-Kelly.

I won't lie; it was strange to watch. Those of us not in the throes of boy band mania have little understanding of why young girls pass out for these men. One Direction, competitors in British reality show The X Factor, rapidly ascended in popularity after the release of their debut single What Makes You Beautiful in September 2011. The Wikipedia page for One Direction alone is testament to the fans’ devotion, with detailed descriptions of each member’s history, personal relationships and bird phobias.

One Direction: From left to right, Louis Tomlinson, Zayn Malik, Niall Horan, Harry Styles and

The scene outside the hotel was reminiscent of when Justin Bieber came to New Zealand; back in 2010, two girls stole Bieber’s hat and held it to ransom, in return for a hug. Odd, perhaps, but not that harmful in the long run. I had barely heard of One Direction, but could still drum up some goodwill towards what I'd just witnessed; the girls all looked like they'd had such an exciting time, even if I couldn't empathise.

While such boy mania has re-emerged in recent years, this brand of hysterical groupie isn't new, of course. Backstreet Boys, *NSync and my personal favourite 5ive inspired it in the 1990s. For more extreme examples, Beatlemania and Elvis come to mind, those early rock n' roll sex symbols who “stuff their crutches [while the] girls wet the seat covers”, as Germaine Greer put it in The Female Eunuch. As pop culture goes, music in particular works as a channel for sexuality, because they are so similar. Like sexuality, musical taste evolves and matures over time; it’s unlikely that One Direction will ever appeal to the post-menopausal, but it works when girls are growing up. Society will make them feel embarrassed for it later, far more so than for their male counterparts and their childish interests. But who, in the end, freely chooses what music they like? Musical taste doesn’t follow the same mental processes as liking certain books or TV shows. The thrumming pounds through your legs up your thighs and your hips move, you are meant to listen to it.

Zadie Smith writes about the phenomenon of the teenage girl crush in her debut novel White Teeth:

Clara's inexplicable dedication to Ryan Topps knew no bounds. It transcended his bad looks, tedious personality and unsightly personal habits. Essentially, it transcended Ryan, for...Clara was a teenage girl like any other; the object of her passion was an accessory to the passion itself, a passion that through its long suppression was now asserting itself with volcanic necessity. Over the ensuing months, Clara's mind changed, Clara's clothes changed, Clara's walk changed, Clara's soul changed. All over the world girls were calling this change Donny Osmond or Michael Jackson or the Bay City Rollers. Clara chose to call it Ryan Topps.

I chose to call it AC/DC, or Led Zeppelin. But, lucky for me, my idols of choice didn't receive the venomous reaction reserved for fans of modern boy band types. Many of my teenage favourite bands upheld the concept of masculinity, singing about exciting drugs, the conquest of women and the thrill of rebellion. I liked them because they gave me the power I wanted (provided I put myself in the male protagonist position and tolerated the misogyny). All the boy band figures, by contrast, are pretty feminine and safe—so safe that their stardom works wonders on pre-pubescent girls. Both the songs and the fandom showcase the only way women are allowed to objectify men and enjoy sex—in a loving, attached, monogamous relationship with the One who makes the girl feel beautiful (because that beauty is earned via romance, not given to her at birth). The girls waiting outside the InterContinental sighed less about sex than about loving and marrying One Direction members. Such romance can turn ugly, and the abuse that gets hurled at boy band stars' girlfriends is no accident. We may as well stop feigning surprise at it, for our culture tells these girls early on that jealousy, insecurity and monomaniacal obsession, at the expense of the principled and independent self, is not just a side effect but a central tenet of romantic relationships. We are taught that Romeo and Juliet is a tragic love story, but the lesson learned is not that relationship addiction is disturbing, just that sometimes love hurts, baby.

Such love-worship on both sides may in part explain many men and women's heavy disdain for boy bands. Their rhetoric of seeking social acceptance via a committed romantic heterosexual relationship can be an alienating idea; many men do not wish to be seen as an accessory to a woman's self-completion, and many women feel complete without a man. Certainly, the more young women were taught to love their autonomous and sexual selves, the further Bieber fever would diminish. But the dominant brand of internet criticism being dished out to One Direction and Justin Bieber will not directly help this along.

Of course, there are plenty of legitimate reasons to dislike these musicians. I personally find the music banal, and the lyrics are politically dubious, as I shall discuss later. But much of the disdain for One Direction and Bieber has a slightly sinister taint to it. The frequent casting of boy band members as gay comes from homophobia coupled with the urgent desire to dismiss and neutralise straight girls’ obsessions. After all, the lyrical and real-life evidence of Bieber and One Direction’s attraction to men is scarce. However, their acts do pose quite a threat to traditional straight masculinity; if women are drawn to these ‘nice guys’, perhaps other men wanting attention will actually have to be nice to women. It’s easier to convince women that One Direction and Bieber aren’t actually attracted to them, so they may as well stop being interested. At the same time, it reinforces the idea that heterosexual attraction is only shown by having a prurient interest in women gyrating, something that arguably hurts both men and women.

Motley Crue - girls, girls, girls (official music video) found onRock

The main crime of One Direction and Justin Bieber seems to be that they sing a lot about how beautiful and lovely girls are. What disgusting, terrible music! So much of cyberspace would have us believe. If I had a dollar for every time someone posted about how terrible Bieber is, I could probably buy his franchise. Bieber hate is outstripped only by the adoration flooded at him by young girls. The criticism of Bieber and One Direction falls on deaf ears—all these girls will hear is people telling them, in no uncertain terms, how much the very thing they find attractive sucks.

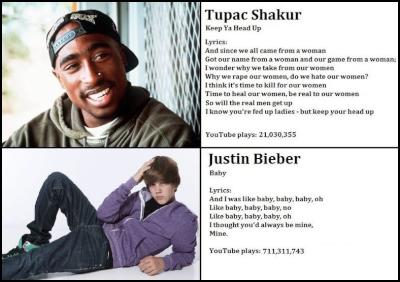

Click for big version.

Yes yes, but guess which musician is a) alive, so b) currently working, and c) crafted primarily to elicit interest from girls growing up in the internet age.

Haters gotta admit, though, there's a wide open space for One Direction and Bieber's rhetoric in the pop culture world. In Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Karl Marx writes: “Religious distress is at the same time the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of a spiritless situation. It is the opium of the people.” Few would take religion (in its extremist and damaging forms) or opium if they did not genuinely suffer in some way. The same follows for obsessive fandom. One Direction's “I’ll be here, by your side, no more fears, no more crying” is a reassurance that is comparatively rare in our culture, and one that many young women clearly need to hear. Many big bands like Radiohead or the White Stripes are largely indifferent to young girls’ concerns, and, worse still, outright misogyny still pervades rock (trigger warning: rape), hip-hop (domestic violence trigger warning, that song is horrible), indie, Britpop and almost any other genre under the sun.

However, while One Direction’s work may partially attempt to address the very real pain of many young women, it can often serve to reinforce it. What Makes You Beautiful jarringly begins with “you’re insecure” (uh, thanks guys, I’d forgotten for a second) and then moves on to praising the woman’s beauty, which she apparently cannot see. This acknowledges many women’s hunger for feeling beautiful, but simultaneously reminds us that someone has said they are not. Similarly, Justin Bieber’s “You're always number one, my prize possession, one and only” sounds encouraging, but puts the girl on a pedestal and promotes the arguably unnecessary idea of needing a) to be wanted like a possession and b) to stand out from the crowd, to be special, to feel unique.

What makes us so desperate to hear that we are beautiful, desirable or special? On some level are we not already beautiful and good by virtue of our existence? Alas, many versions of Christianity, a religion which has helped shape Western morality for centuries, say otherwise. Being beautiful only becomes a question if we perceive the self as something distinct from the rest of the world, born inherently flawed and thus in need of development and redemption. The woman is hit particularly hard by this; created from a rib, she is responsible for man’s fall from grace, and is destined to suffer disproportionately from then on. This demonisation of woman suits an ongoing patriarchal model that tells women they are ugly and wrong.

But there is an alternative. Perhaps if instead we saw all humans not as imperfect beings, but as a small part of a benevolent interconnected network, as in many shamanistic religions, people would be wonderful because they are; not needing to weigh up our good deeds against bad, beauty against ugliness. In such a culture, One Direction and Justin Bieber would not need to tell girls they are beautiful, because they would already know it.

Until we overhaul not just celebrity culture, but the entire way in which our culture perceives women--and indeed, all people--One Direction, Bieber and their ilk may remain a tempting palliative for young women’s self-esteem issues. The criticism of that sort of fandom is often as oddly hysterical as the fandom itself; One Direction and Bieber aren't really much more lowbrow than Transformers 2, the All Blacks or Limp Bizkit. Besides, dominant pop culture at any given time is, by and large, a bit stupid, full of ephemeral stars catering to what many perceive as shallow needs. The internet may yet change this, creating horizontal power structures where every man and his rainbow can become famous. But for the moment, the old vanguards are still up. Women are told they are ugly and that subjective sexuality is none of their business; Bieber and One Direction come along to reassure young women that they are beautiful and desirable; girls fall into screaming fandom, and the internet is right there to feign outrage at this hysteria, all the while providing a substantial dose of slut-shaming to push their barely visible sexuality back in the closet. The cycle goes on.

ENDS

Gordon Campbell: On Our Austerity Fixation And Canada Staying Centre-left

Gordon Campbell: On Our Austerity Fixation And Canada Staying Centre-left Ramzy Baroud: Screaming Soldiers And Open Revolt - How One Video Unmasked Israel's Internal Power Struggle

Ramzy Baroud: Screaming Soldiers And Open Revolt - How One Video Unmasked Israel's Internal Power Struggle Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - It's An Election, Not A Coronation

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - It's An Election, Not A Coronation Ian Powell: The Dirtiest Of Politics And A Tale Of Two MPs Cloaked In Hypocrisy

Ian Powell: The Dirtiest Of Politics And A Tale Of Two MPs Cloaked In Hypocrisy Gordon Campbell: On A Neglected, Enduring Aspect Of The Francis Era

Gordon Campbell: On A Neglected, Enduring Aspect Of The Francis Era Eugene Doyle: 50 Years After The “Fall” Of Saigon - From Triumph To Trump

Eugene Doyle: 50 Years After The “Fall” Of Saigon - From Triumph To Trump