Rhema Vaithianathan - Fresh Ideas for a Productive Economy

Notes for Fabians Seminar "Fresh Ideas for a

Productive Economy"

July 2011 - Legislative Chamber, NZ

Parliament

Management training for dummies...

Rhema Vaithianathan

University of Auckland

Rhema Vaithianathan – Auckland University

International evidence is increasingly pointing to management skills and processes as an important part of the productivity puzzle. Countries such as the US, Japan and Sweden consistently score higher on various measures of management skills and techniques whilst New Zealand management scores in the middle to poor range. Indeed, New Zealand managers are strikingly bad at retaining outstanding staff. This, rather than the wage gap, might be the most significant reason for losing so many people to Australia. The World Bank has been running management skills courses for small to medium sized firms in developing countries and preliminary findings are apparently positive. I propose that New Zealand, too, develops a comprehensive management training programme for small to medium sized manufacturing firms and family farms.

We don’t

need another knowledge wave…

The problem for New Zealand’s economy is clear – but solutions elusive. Any economist can all describe the size of the challenge – and the 2025 taskforce did a very good job of doing that. But good economists, like good doctors, should offer effective treatment, not just accurate diagnosis.

The 2025 taskforce offers us a 20th Century cure for a 21st Century ailment. Their prescription of privatization, benefit curtailment and market liberalization are familiar, old fashioned and unlikely to work. It might be a solution – but not for the current problems which beset New Zealand.

New Zealand’s productivity is low and falling; our gap with Australia is large and rising. We spend more hours at work yet produce less value per hour (Statistics New Zealand, 2010).

It is often argued that the reason for New Zealand’s decline is that we are over exposed to commodities – which are exported with little or no value added. Commentators up and down the country are repeating the familiar mantra: we need to diversify our economy and add value. Politicians and business leaders form taskforces and working bees, turning their brains to what the next big opportunity for New Zealand might be. Is it the movie industry? Is it the green economy? Is it mining our conservation estate?

Knowledge Waves are launched, Reports are released and invitations to policy launches crowd our mantle pieces. What invariably follows is bitter disappointment. Most of these attempts are strong on motivational speeches but very weak on specific policy recommendations.

In a modern free-market economy such as New Zealand, the sectors in which New Zealand trades are the sectors in which individual firms choose to trade. We specialize in commodities not because Government is directing us to do so but because individual New Zealanders – for good or ill –- choose to work as farmers. Entrepreneurs and capital owners choose to invest in forests and to export the raw timber. Unless these business owners have the skills and capacity to add value, or they see profit in doing so, there is little that Governments can (or ought) to do.

For this Fabian talk, we were asked to eschew Tony Robbins economics, which is based on exhorting New Zealanders to save, add value or capture the knowledge wave. Instead, we were given a more mundane brief: come up with a specific idea or policy for improving New Zealand’s productivity.

My suggestion is rather modest: to extend any R&D tax credit to management training for medium sized New Zealand firms.

New Zealand managers are poor

at managing people

My proposal relates to an exciting line of inquiry by Nicholas Bloom and John Van Reenen (Nicholas Bloom and John Van Reenen, 2007) who have unearthed an amazing correlation between the degree of management skills in a country and the country’s productivity.

In cross-country regressions, they have found that countries which score more highly on a specially developed management survey, have higher productivity. They report that “management practices can account for up to a third of the differences in productivity between firms and countries”. (Nicholas Bloom and John Van Reenen, 2007).

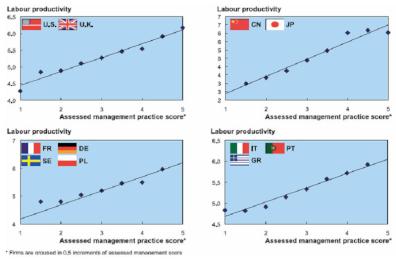

The link between labour productivity and management practice scores are found to be independent of country and culture (Nick Bloom et al., 2007). Figure illustrates the management practice scores and labour productivities of firms in various countries. The strong positive correlation is striking.

Click for big version

Figure : Labour Productivity and Management Scores of Manufacturing Firms in Bloom and van Reenen’s sample

Their data moreover suggests that a 1 point increase in management score is equivalent to a 65% increase in invested capital. In other words, New Zealand can overcome its low capital-to-labour ratio and poor labour productivity with improvements in management skills.

However, New Zealand’s management scores are not very good. The MED commissioned a New Zealand version of the Bloom and van Reenen index (Roy Green and Renu Agrawal, 2011). They interviewed 152 medium and large manufacturing firms. These firms were measured on their management practices across a broad range of abilities. Overall, New Zealand management is low to middling. However, New Zealand is significantly worse in the people management dimension – in particular, in the area of recruiting and retaining talent (Table ).

Best practice : Poor performers are moved to less critical roles or out of the company as soon as weaknesses are identified

Worst practice: Poor performers are rarely removed from their positions

Promoting high performers - Ranked 13th out of 16 countries

Best practice: Top performers are actively identified, developed, and promoted

Worst practice: People are promoted primarily upon the basis of tenure

Retaining high performers - Ranked 14th out of 16 countries

Best practice : Managers do whatever it takes to retain top talent

Worst practice : Managers do little to try and keep the top talent

Table : Worst performing dimension for New Zealand Management Scores. Source: (Roy Green and Renu Agrawal, 2011)

Market liberalisation

is not the answer for New Zealand

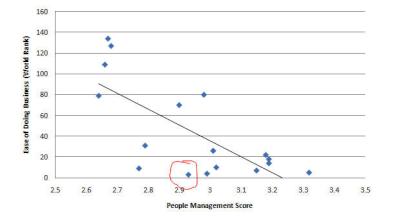

Of course, the 2025 taskforce argued that New Zealand’s poor productivity comes down to labour and product market rigidities. In general there is a correlation between free-markets and management scores. Figure illustrates the positive correlation between a measure of market freedom (the country’s rank in the World Bank’s ease of doing business index) and the country’s overall People Management Score.

Click for big version

Figure : Ease of Doing Business and Management Score. (Source: World Bank Ease of Doing Business Survey and Green & Agrawal, 2011)

What Figure shows is that if you are China, Greece or India, market liberalisation might be a useful avenue to pursue. However, New Zealand already has exceedingly free markets.

All those countries which scored better in overall management than New Zealand also ranked below New Zealand on ease of doing business.

Having dismissed the idea that improving management scores is associated with market liberalization, what else could Government do to improve managerial competence?

An R & D tax credit for management

skills

Management scores are found to be correlated with tertiary qualifications of managers. New Zealand has one of the lowest rates of tertiary education of managers in the sample (Roy Green and Renu Agrawal, 2011). One reason for this is the high degree of optimism that New Zealand managers demonstrate about their own competency. Optimism encourages managers and entrepreneurs who have low skill levels to start businesses that they might have little ability to run well. The high level of self-belief also dissuades them from taking up the opportunity to improve management skills. Recent work in developing countries suggests that simple measures to upgrade managerial competence can have a major impact on firm productivity (Nicholas Bloom et al., 2011).

My suggestion is that management training be included in a Research and Development tax credit scheme. The scheme should target only New Zealand firms which are medium size. Firms which send their mid-level managers or owner operators to accredited management training programmes will be eligible for a tax reduction similar to that of an R&D write off. Clearly, if the firm’s profitability increases in the following years, the tax returns will be higher and the tax revenues from the firms will partially fund the intervention.

Bloom, Nicholas and John Van Reenen. 2007. "Measuring and Explaining Managment Practices across Firms and Countries." Quarterly Journal of Economics, 72(4), pp. 351.Bloom, Nicholas; Benn Eifert; Aprajit Mahajan; David McKenzie and John Roberts. 2011. "Does Management Matter? Evidence from India," In NBER Working Paper No. 16658.

Bloom, Nicholas and John Van Reenen. 2007. "What Drives Good Management around the World?" CentrePiece, Autumn, pp. 12-17.

Bloom, Nick; Stephen Dorgan; John Dowdy and John Van Reenen. 2007. "Management Practice and Productivity: Why They Matter," In. London: London School of Economics.

Green, Roy and Renu Agrawal. 2011. "Management Matters in New Zealand: How Does Manufacturing Measure Up? ," In Ministry of Economic Development Occasional Paper 11/03. Wellington.

Statistics New Zealand. 2010. "Comparing the Income Gap between Australia and New Zealand," In. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand.

Rhema Vaithianathan,

Ph.D., is currently the Director of the Centre for Applied

Research in Economics and an Associate Professor in

Economics at the University of Auckland. Previously, she was

a research fellow at Australian National University, an

independent economic consultant and policy analyst at the

New Zealand Treasury. She was a Harkness Fellow at Harvard

and a Foreign Scholar at Hitotsubashi University in Japan.

She has published widely in health economics,

entrepreneurship and development economics. She was awarded

an University of Auckland's Business School Research

Excellence Award. She earned both her doctorate in economics

and master's of commerce from the University of

Auckland.

Rhema Vaithianathan,

Ph.D., is currently the Director of the Centre for Applied

Research in Economics and an Associate Professor in

Economics at the University of Auckland. Previously, she was

a research fellow at Australian National University, an

independent economic consultant and policy analyst at the

New Zealand Treasury. She was a Harkness Fellow at Harvard

and a Foreign Scholar at Hitotsubashi University in Japan.

She has published widely in health economics,

entrepreneurship and development economics. She was awarded

an University of Auckland's Business School Research

Excellence Award. She earned both her doctorate in economics

and master's of commerce from the University of

Auckland.

Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia

Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal

Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest

Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels

Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels Keith Rankin: Remembering New Zealand's Missing Tragedy

Keith Rankin: Remembering New Zealand's Missing Tragedy