Personal Income Tax Reform in New Zealand

by Keith Rankin, 7 February 2010

We have heard a lot of talk recently about how New Zealand's tax system is broken and that it requires radical surgery, the latest being the January 20 Report of the Victoria University tax working group (http://www.victoria.ac.nz/sacl/cagtr/pdf/tax-report-website.pdf), and the surrounding media commentary.

While I agree that the system is far from perfect, few of us understand the basics of our present personal tax scales, and workable suggestions of alternatives are few and far between.

A major problem is that the tax system and the benefit system now substantially overlap, and we no longer have clear principles defining where the boundaries between the two systems lie.

While some believe that there are no boundaries, and that taxes and benefits are two parts of a single system, I would not go that far. Here I propose two clear definitions of each concept, and suggest some basic reforms to the personal tax scales, based on either definition of what taxes are.

- Personal taxes are actual payments levied by governments on tax-resident persons. Benefits are payments made by governments to tax-resident persons. This the definition is based on the direction of the payment. By this definition, neither taxes nor benefits can be negative amounts.

- Personal taxes are payments levied on or granted to tax-residents by governments on an individual basis. Taxes may be negative. Benefits are payments granted to households.

The second definition is I believe the one that provides the best basis for sustainable reform of both taxes and benefits. Nevertheless the first definition is closer to the popular view, and it is necessary to offer suggestions for reforming personal taxation while regarding taxation as a stand alone system.

This paper looks at

personal tax reform from an individual point of view. A

subsequent paper will consider the tax and benefit

ramifications of raising children.

This paper looks at

personal tax reform from an individual point of view. A

subsequent paper will consider the tax and benefit

ramifications of raising children.

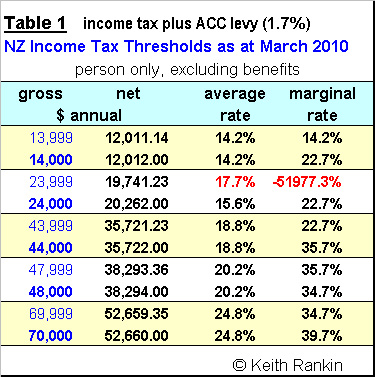

Table 1 presents the main features of our present tax scale. It includes the 1.7% employee levy for ACC (Accident Compensation) and the $520 "Independent Earner " concession available to persons earning in the $24,000 to $44,000 range. It makes no allowance for benefits that a person might qualify for. In line with definition 1, current tax scales do not (and can not) allow for a negative average tax rate.

Conventional tax scales are de¬fined by a set of marginal rates, which apply to income earned above a threshold (in blue) for that rate. Thus persons earning $14,000 or less per year pay 14.2% on every dollar earned. Once earnings exceed $14,000 (the first threshold) they pay 22.7% on subsequent dollars earned. For persons earning more than $14,000 per year, the marginal rate (on the last dollar earned) always exceeds the average rate, except where strange anomalies exist. Further, the average tax rate rises continuously as earnings exceed the first threshold.

The major problems with the present New Zealand scale are: higher average tax rates, compared to other countries, on lower incomes; the strange anomaly in which a person earning $23,999 pays nearly $520 more tax than a person earning $24,000; and the fact that the higher marginal tax rates are above the company tax rate (of 30%).

The latter problem, while the most publicised, is the least important. It's normal overseas for marginal tax rates to exceed 40%, whereas company tax rates are rarely over 40%. There are ways to address this problem other than to eliminate all marginal rates above 30%.

My focus here is on the other two problems, and in particular on how to make personal tax scales more equitable without raising the highest marginal rate.

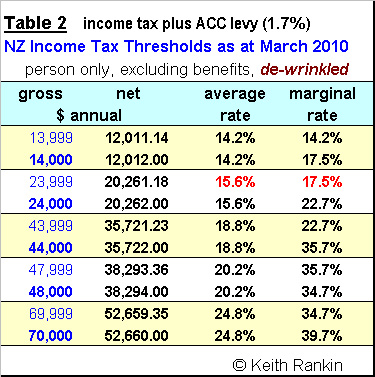

First, Table 2 shows the

result of removing the $24,000 wrinkle in the present scale.

The solution is to replace the Independent Earner Tax Credit

(IETC) introduced in April 2009, by creating a 15.8%

marginal tax rate – 17.5% when combined with ACC – for

incomes above $14,000 and under $24,000, and a 34% marginal

tax rate – 35.7% when combined with ACC – for incomes

between $44,000 and $48,000. Only "independent persons"

earning between $14,000 and $24,000 would pay less tax, and

nobody would pay more tax. It is an easy and inexpensive

reform to commit to. (Independent persons are defined as

persons receiving no benefits, as per definition 1.)

First, Table 2 shows the

result of removing the $24,000 wrinkle in the present scale.

The solution is to replace the Independent Earner Tax Credit

(IETC) introduced in April 2009, by creating a 15.8%

marginal tax rate – 17.5% when combined with ACC – for

incomes above $14,000 and under $24,000, and a 34% marginal

tax rate – 35.7% when combined with ACC – for incomes

between $44,000 and $48,000. Only "independent persons"

earning between $14,000 and $24,000 would pay less tax, and

nobody would pay more tax. It is an easy and inexpensive

reform to commit to. (Independent persons are defined as

persons receiving no benefits, as per definition 1.)

The next commitment should be to use the postponed 2011 tax cuts as a launching pad for any further reform. These tax cuts, which favoured middle-income recipients and were voted for in 2008, must take precedence over any alternative cuts suggested in recent reports which have not been voted for and which relatively favour persons on high incomes.

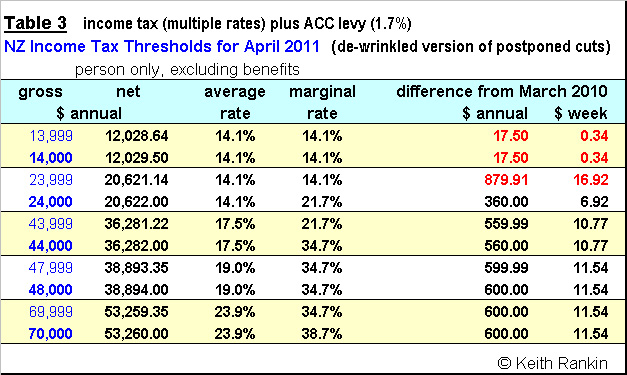

Table 3 shows the postponed April 2011 scale, with the IETC wrinkle once again ironed out, and with differences shown from the present Table 1 scale. While persons earning $14,000 or less will not benefit much, the scale at least will be simple, coherent, and democratic.

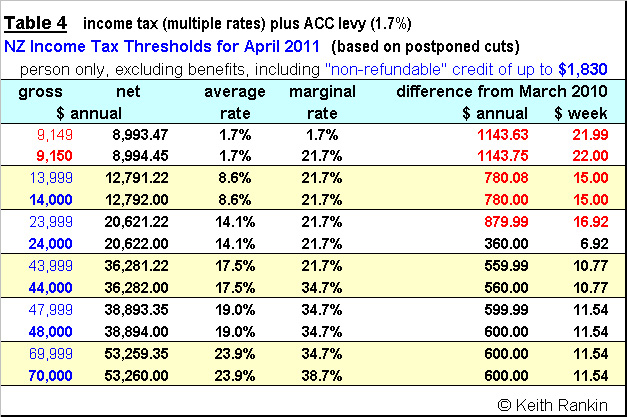

The final reform of this sequence is to introduce a "non-refundable tax credit" of $1,830 per year (Table 4). Such tax credits currently operate in Ireland and Canada, and operated in New Zealand between 1973 and 1978. In New Zealand's case, the 1970s "personal tax rebate" (as it was then called) was allowed to erode in the face of heavy inflation, and was abolished in the belief that lower marginal taxes for middle-income workers were a higher priority than low average taxes for low income workers.

The non-refundable tax credit shown in Table 4 is the equivalent of a zero tax rate on incomes under $9,150. (Thus the only income tax payable by persons earning less than $9,150 would be the ACC levy of 1.7%.) This tax cut for persons on very low incomes would not affect anyone earning more than $24,000, thanks to a rise in the marginal tax rate to 20% (21.7% with ACC) for persons earning above $9,150. Only persons earning under $24,000 would be affected by this reform. Persons earning less than $14,000 per year – the overlooked ones – would finally receive meaningful tax cuts.

All of these steps are technically very easy to do, create scales that are more equitable without increasing anyone's taxes, and represent a low fiscal cost to the government.

There are limits, however, to how far you can take tax reform, by refusing to allow for negative taxes. If we shift to definition 2, then the realm of taxation is the individual and the u of benefits is the household. Thus one agency – the Inland Revenue Department (in New Zealand) – focuses only on individuals and keeps nor records of the household circumstances of tax residents. Another agency – Work and Income (in New Zealand) – pays benefits on the basis of household circumstances.

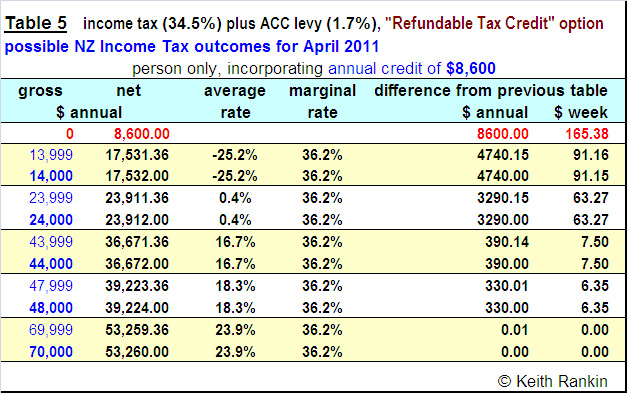

Moving to this definition enables us to adopt the simplest and most elegant solution of all, the "refundable tax credit". This reform option (RTC), shown in Table 5, works as a negative income tax for low earners; in other words a low individual benefit that does not have to be applied for.

The illustration given here is based on the individual unemployment benefit for a married person – $158.65 per week in March 2010 – with two years of adjustment for inflation. ($165.38 is 4.2% above $158.65.)

By using a single tax rate of 34.5% (36.2% with ACC included). The RTC option makes no difference to a tax-resident earning $70,000, compared to the "non-refundable tax credit" option of Table 4. For persons earning over $70,000 the RTC option represents a tax cut, because the marginal rate falls from 38.7% in Table 4 to 36.2% in Table 5.

The average tax rate becomes negative for persons earning under $24,000. Under definition 1, we would call this negative tax a benefit. Under definition 2, the weekly payment of $165.38 is understood as a true tax credit. For transitional purposes, the differences in weekly net payments, which can range between $0 for someone earning $70,000 per year and $165.38 for someone with zero earnings, can be understood as the first part of an existing benefit.

Most individuals earning under $24,000 qualify for some form of benefit today – typically a primary benefit such as Unemployment Benefit, Sickness Benefit, Invalids Benefit, Student Allowance and/or an Accommodation Supplement. The proposed refundable tax credit of $165.38 per week – effective from April 2011 – would substantially replace such benefits.

A welfare agency – Work and Income – would still be required to apply negative equity (defined as treating people with different circumstances differently). For example, if Unemployment Benefits are 4.2% higher in April 2011 than in March 2010, then an unemployed person over 25 living independently would be receiving $198.39 plus an Accommodation Supplement. Such persons, if they have no earnings, might therefore require a Work and Income benefit of say $100 per week – subject to earnings-related-abatement – in addition to the refundable tax credit that they are automatically entitled to. Many such persons would not bother applying for small benefits, preferring to avoid engagement with a government authority such as Work and Income. Thus, the welfare agency would operate on a much smaller scale once this kind of reform is introduced.

Another advantage of the Table 5 tax reform is that, with a constant marginal tax rate, married couples pay the tame total tax whether they individually have very similar or very different incomes. Thus the case for "income splitting tax credits" disappears in the face of this wider reform.

To conclude, reform of personal taxation is possible, with elegance and simplicity, and without a substantial change in the distribution of income. The proposals suggested all address the tax inequities faced at present by low income workers; generally workers on low wages or short time. Further they reduce the amount of bureaucracy that New Zealanders must face, while raising the incentives for people to raise their incomes.

Other aspects of tax reform – for example issues related to families, company taxation, property investment, expenditure taxes – still need to be addressed. Nevertheless, the proposals advanced here represent a practical kernel to which these other areas can be related.

Keith Rankin

Dept of Accounting and

Finance

Faculty of Creative Industries and

Business

Unitec New Zealand

Email: krankin @

unitec.ac.nz

Ian Powell: Gisborne Hospital Senior Doctors Strike Highlights Important Health System Issues

Ian Powell: Gisborne Hospital Senior Doctors Strike Highlights Important Health System Issues Keith Rankin: Who, Neither Politician Nor Monarch, Executed 100,000 Civilians In A Single Night?

Keith Rankin: Who, Neither Politician Nor Monarch, Executed 100,000 Civilians In A Single Night? Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight

Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine

Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor

Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor