The Moomins, and their gift of tolerance

The Moomins, and their gift of tolerance

by Gordon Campbell Originally Published on Werewolf.co.nz

After the Moomin books

started to be translated from Finnish into English in the

late 1950s, several early critics clearly couldn’t figure

them out. Sure, the books were odd and amusing enough –

but the tales had no obvious beginning or end, and no

discernible symbolic meaning. In fact, the plump little

beings with tails who were at the centre of the stories

didn’t seem to carry out a quest or experience any life

lesson at all during the course of the stories. Moreover,

there was no Alice or Christopher Robin to act as a

re-assuring human guide in this strange environment. Not

quite as intelligent as their British equivalents, one

English reviewer concluded.

After the Moomin books

started to be translated from Finnish into English in the

late 1950s, several early critics clearly couldn’t figure

them out. Sure, the books were odd and amusing enough –

but the tales had no obvious beginning or end, and no

discernible symbolic meaning. In fact, the plump little

beings with tails who were at the centre of the stories

didn’t seem to carry out a quest or experience any life

lesson at all during the course of the stories. Moreover,

there was no Alice or Christopher Robin to act as a

re-assuring human guide in this strange environment. Not

quite as intelligent as their British equivalents, one

English reviewer concluded.

Well, we’re younger than that now, and can readily cope with all of the above. Yes, the early Moomin books are rambling and episodic, but their whole atmosphere of fertile chaos is very much the point. She hadn’t set out to educate anyone, Tove Jansson once wrote. ‘I try to describe what fascinates and frightens me, what I see and remember, and I let it all take place around a family whose main characteristics are probably a kindly confusion, an acceptance of the world around it, and the very unusual way in which its members get on with each other.’ As some perceptive critics have noted, child readers can readily accept a story where the author’s eye wanders off to other characters and events, perhaps because childhood itself can be just as diffuse and generous. In Moominvalley all comers are welcome, and everyone is precious.

On the surface, Moomintroll is the central figure. He looks like a round little hippo, and has a touch of Charlie Brown’s tender-hearted naivete about him. It is Moominmamma though, who provides the emotional binding for the entire series. In fact, she could be the supreme example of the motherhood principle in all of children’s literature. As Alison Lurie pointed out in a 2003 essay, there is no childhood anxiety, no bickering between siblings, no cosmic threat or flood that cannot be resolved by Moominmamma’s calming presence and soothing words, or by liberal servings of the pancakes, birthday cake, blueberry pie, raspberry juice, coffee and jam sandwiches that flow from her kitchen.

Usually, it is risky

to assume a writer of fiction has been trading directly on

their own life experience, but Jansson has made it clear

that her own famous parents were the models for Moominpappa

and Moominmamma. Her father was the renowned sculptor

Viktor Jansson, and some of his work can be seen

here and here.

In the books, Moominpappa comes across as an energetic

bundle of masculine vanity, self-absorbed to the point of

folly. According to his daughter, Viktor did not exhibit

those traits so much - but like his fictional counterpart,

Viktor did have a love of the sea and for the bracing perils

of outdoors adventure. Jansson’s mother was the artist

Signe Hammersten Jansson, who designed Finland’s

bank-notes and over 200 of the country’s postage stamps.

Usually, it is risky

to assume a writer of fiction has been trading directly on

their own life experience, but Jansson has made it clear

that her own famous parents were the models for Moominpappa

and Moominmamma. Her father was the renowned sculptor

Viktor Jansson, and some of his work can be seen

here and here.

In the books, Moominpappa comes across as an energetic

bundle of masculine vanity, self-absorbed to the point of

folly. According to his daughter, Viktor did not exhibit

those traits so much - but like his fictional counterpart,

Viktor did have a love of the sea and for the bracing perils

of outdoors adventure. Jansson’s mother was the artist

Signe Hammersten Jansson, who designed Finland’s

bank-notes and over 200 of the country’s postage stamps.

“My mother especially,” Jansson once wrote, “ had an unusual capacity for mixing stern morality with an almost exhilarating tolerance. It is a quality I have never met in anyone else.” Again, that is an almost perfect description of Moominmamma – who is eternally caring and inclusive to a fault, while staying firmly in charge of the rituals of home life. In Finn Family Moomintroll, she is the only person who can identify her child after he has been physically altered by the Hobgoblin’s hat. Ultimately, she recognizes her son by his eyes –which is good work, even for a mother.

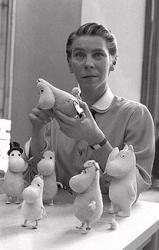

J ansson (in centre of photo with her

mother and her partner Tuuliki Pietila) started writing the

Moomin books in 1945, and stopped in 1970. As many have

noted, the books fall into at least three stages, each

different in tone and narrative coherence. There are the

loose and carefree early adventures – Comet in Moominland,

Finn Family Moomintroll ( which, for new readers, is

probably the best starting point ) and Exploits of

Moominpappa. In the mid 1950s, she wrote the more

structured tales Moominland Midwinter and Moominsummer

Madness, still probably the most purely enjoyable stories in

the Moomin saga.

J ansson (in centre of photo with her

mother and her partner Tuuliki Pietila) started writing the

Moomin books in 1945, and stopped in 1970. As many have

noted, the books fall into at least three stages, each

different in tone and narrative coherence. There are the

loose and carefree early adventures – Comet in Moominland,

Finn Family Moomintroll ( which, for new readers, is

probably the best starting point ) and Exploits of

Moominpappa. In the mid 1950s, she wrote the more

structured tales Moominland Midwinter and Moominsummer

Madness, still probably the most purely enjoyable stories in

the Moomin saga.

What makes the Moomin stories so enjoyable - and so popular with parents as well as children – is the wit, compassion and energy present in such abundance. Adults and children respond alike to the same elements in these books, which is quite a rare event. More commonly these days in films like Shrek there is a pratfall for the kids and then a knowing wink – aimed right over the heads of the children – at the adults who brought them. For a while at least, Jansson could strike the same note simultaneously in the youngest child and in the most sophisticated adult reader.

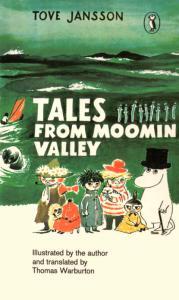

In the 1960s, the tone of the stories shifted again. To my mind, the short story collection Tales of Moominvalley ( published in 1962) is Jansson’s high point. It also serves as a useful bridge to the two final dramas of separation and self-discovery ( Moominpappa at Sea and Moominvalley in November ) that are barely children’s books at all. Jansson’s mother died in 1970, the same year Moominvalley in November was published.

That last, sombre

Moomin book is very much about coping with loss, and with

the realization that family and childhood are no longer

emotionally accessible - not in any idealized way at least,

than can offer comfort. “I could no longer find my way

back to that happy valley,” Jansson once wrote, in

explaining her decision to effectively close the page on the

Moomins. Or again : “ There has been a very clear line,

in my work, in the course of which my books have become less

and less childish. I finally reached the point where I

simply couldn’t write for children anymore....perhaps

because I wasn’t sufficiently childish myself anymore.’

In an echo of these sentiments, the characters in

Moominvalley in November gradually discover a proper time

and method of moving on from childhood. For the last 30

years of her life, Jansson concentrated on writing adult

fiction.

That last, sombre

Moomin book is very much about coping with loss, and with

the realization that family and childhood are no longer

emotionally accessible - not in any idealized way at least,

than can offer comfort. “I could no longer find my way

back to that happy valley,” Jansson once wrote, in

explaining her decision to effectively close the page on the

Moomins. Or again : “ There has been a very clear line,

in my work, in the course of which my books have become less

and less childish. I finally reached the point where I

simply couldn’t write for children anymore....perhaps

because I wasn’t sufficiently childish myself anymore.’

In an echo of these sentiments, the characters in

Moominvalley in November gradually discover a proper time

and method of moving on from childhood. For the last 30

years of her life, Jansson concentrated on writing adult

fiction.

All the same, it wasn’t a total break. In later years, Jansson devoted a vast amount of her time to correspondence with the thousands of children from around the world, who kept writing to her about the books. Many would address their letters to “Dear Moominmamma.” As Nancy Lyman Huse wrote in an interesting essay in 1991 about this correspondence, Jansson was being pushed into extending her own understanding of what the books actually contain, while discharging a sense of responsibility towards her thoughtful young readers. As she once said to a librarian, you can’t very well leave a letter from a child, unanswered.

One English boy wrote to her : ‘I enjoy the Moomins so much because they are so unreal in form, and so real in person.’ No author, Jansson wryly responded, could ask for a higher compliment.

Jansson was born in 1914 and died in

2001 at the age of 87. In Moominvalley, she created a

fictional universe as fully realized – to take one

recurring comparison – as the 100 Acre Wood of A. A.

Milne. Think about it : rural setting, naïve hero, much

good nature and whimsy, creatures who seem part animal, part

human. Milne’s world though is resolutely male-centered (

Kanga excepted) and was inspired, reportedly, by his

father’s experience with a school for boys.

Jansson was born in 1914 and died in

2001 at the age of 87. In Moominvalley, she created a

fictional universe as fully realized – to take one

recurring comparison – as the 100 Acre Wood of A. A.

Milne. Think about it : rural setting, naïve hero, much

good nature and whimsy, creatures who seem part animal, part

human. Milne’s world though is resolutely male-centered (

Kanga excepted) and was inspired, reportedly, by his

father’s experience with a school for boys.

Jansson’s world is far more female-oriented. It does contain one stereotyped female character ( the Snork Maiden) but it also offers several strong female characters besides Moomimamma ( eg Too-Ticky, Little My and the Groke) and this strength is expressed in quite different ways. The nervous and neurotically house-proud Fillyjonk is also a stereotype. Yet in Tales of Moominvalley she is a very memorable one - a woman who gets liberated ( by a tornado !) from her anxious attachment to her domestic possessions.

While the Moomin family is usually the heart of the action, the freewheeling, bohemian universe of Moominvalley also contains a brilliant cast of minor characters. The wandering artist Snufkin is a free spirit who was clearly an alter ego for Jansson, and it is his image that graces the last page of the last Moomin book.While Snufkin lives the lonesome creative life to the hilt, he is also regularly inspired by the prospect of meeting up again with his friends.

Other minor players are also grounded in real life. Too Ticky, who was based on Jansson’s own lesbian partner Tuulikki Pietila offers Moomintroll much good advice and encouragement during Moominland Midwinter – just as in real life, Pietila counselled Jansson through a period of writers block, overwork and depression during the 1950s. As Lurie says, it is largely due to Too-Ticky’s urging that Moomintroll learns how to ski, gets to see the Northern Lights, and reaches a new plateau of maturity. ‘One has to discover everything for oneself,’ Tooticky says, foreshadowing the darker themes of Moominvalley in November, “ And get over it all alone.”

For many readers,

their favourite character is the tiny, gleefully uninhibited

brat called Little My – a primal force who constantly

provides a snarky commentary on the good-natured Moomins.

Beyond them again are other recognisable types, even in

translation from the Finnish. I particularly liked the bluff

and bureaucratic Hemulens. ‘All round him there were

people living slipshod and aimless lives. Everywhere

wherever he looked there was something to put right, and he

worked his fingers to the bone trying to get them to see how

they ought to live.” Most Hemulens are male, though all of

them wear skirts.

For many readers,

their favourite character is the tiny, gleefully uninhibited

brat called Little My – a primal force who constantly

provides a snarky commentary on the good-natured Moomins.

Beyond them again are other recognisable types, even in

translation from the Finnish. I particularly liked the bluff

and bureaucratic Hemulens. ‘All round him there were

people living slipshod and aimless lives. Everywhere

wherever he looked there was something to put right, and he

worked his fingers to the bone trying to get them to see how

they ought to live.” Most Hemulens are male, though all of

them wear skirts.

As the US critic Shelley Jackson pointed out in this brilliant obituary for Jansson, even the most timid residents of Moominvalley maintain a self image that “inside their fussy rotundity is an adventurer of the first water, and that if they felt like it, they could show a few people a thing or two.” This may be a Finnish trait, but it is a New Zealand one as well. A prime example is the little dog Sorry-Oo, who dreams of running with the wolves and finally does so – only to discover, almost too late, that they are eyeing him up as lunch.

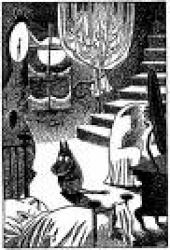

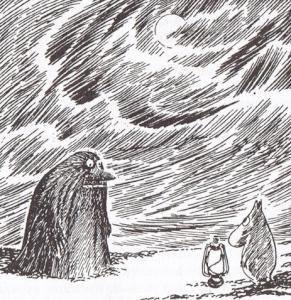

One should also mention those beings

in Moominvalley that are like nothing else in literature,

save perhaps in Lewis Carroll’s wilder moments. Best of

all is the cold and lonely Groke, who is drawn inexorably to

warmth and flame, but who freezes whatever she touches, and

lays barren everywhere she sits. By the time we get to

Moominpappa at Sea, a near teenage Moomintroll has entered

into a dangerous kinship of sorts with the Groke. He goes

down alone to the beach with a lamp that he swings back and

forth - and the Groke dances towards him, swaying in her

passage across the grey waves in time to the movements of

the lamp.

One should also mention those beings

in Moominvalley that are like nothing else in literature,

save perhaps in Lewis Carroll’s wilder moments. Best of

all is the cold and lonely Groke, who is drawn inexorably to

warmth and flame, but who freezes whatever she touches, and

lays barren everywhere she sits. By the time we get to

Moominpappa at Sea, a near teenage Moomintroll has entered

into a dangerous kinship of sorts with the Groke. He goes

down alone to the beach with a lamp that he swings back and

forth - and the Groke dances towards him, swaying in her

passage across the grey waves in time to the movements of

the lamp.

The episode with the Groke - and Moomintroll’s crush on a gorgeous and unattainable sea-horse - are two striking sequences in a book in which almost every beloved character from the earlier books (including Moominmamma ) is going through an identity crisis. In her case, it involves a mental breakdown of sorts. Distractedly, Moominmamma begins to fade into the murals that she obsessively paints on the lighthouse to which her husband has dragged the family, in a doomed attempt to get back to nature. On this island, nature itself lives in terror of the Groke.

In the last book Moominvalley in November, things reach the only, logical conclusion. Each character waiting for the family’s return from the island finds a reason to leave, and begins a life without the Moomins. Only the orphan Toft remains, and even he gets a headache whenever he thinks about Moominmamma : “She had grown so perfect and gentle and consoling that it was unbearable, she was a big round balloon with a face…” As Shelley Jackson explains this passage in her obituary article : ‘It is not until Toft lets go of this mother-balloon that he spots the faraway light of family sailing home, though the book ends before they can be united. When I realised that Jansson wrote this the year that her own mother died, all the hair on my arms stood up..’

By focusing on the darker, more

complex conclusion of the Moomins, I hope I haven’t put

off any latecomers. All it means is that these books need to

be read in sequence. The high spirit of the first five books

is peerless. And to my mind, the complex and melancholy

elements that come to the fore in the last two books only

make the entire series more admirable. The illustrations

are also exceptional. Jansson had spent the first decade of

her creative life trying to carve out a career as a painter,

and the drawings have always been an integral part of the

books’ enduring success. From 1954 onwards, a Moomins

comic strip that was drawn initially by Jansson ( and later,

by her brother) also became popular, world-wide. It is

available in at least three volumes, and is recommended –

though it has a singular atmosphere, different in tone and

in content again, to any of the books.

By focusing on the darker, more

complex conclusion of the Moomins, I hope I haven’t put

off any latecomers. All it means is that these books need to

be read in sequence. The high spirit of the first five books

is peerless. And to my mind, the complex and melancholy

elements that come to the fore in the last two books only

make the entire series more admirable. The illustrations

are also exceptional. Jansson had spent the first decade of

her creative life trying to carve out a career as a painter,

and the drawings have always been an integral part of the

books’ enduring success. From 1954 onwards, a Moomins

comic strip that was drawn initially by Jansson ( and later,

by her brother) also became popular, world-wide. It is

available in at least three volumes, and is recommended –

though it has a singular atmosphere, different in tone and

in content again, to any of the books.

As mentioned, I think the short story collection Tales of Moominvalley is the high water mark of the series. The best known story in this volume is undoubtedly ‘The Invisible Child.’ In this much anthologized story, a child called Ninny has faded away. Ninny has had the misfortune to run afoul of an ‘icily ironical” type of adult who used ridicule as a method of discipline, and who ‘had taken care of her without really liking her.’

The story relates Ninny’s journey back to life, and to visibility. Eventually, the unloved child becomes a boisterous member of the Moomin family. Her emergence into sight is funny, and touching. Her paws ‘ very small, with anxiously bunched toes’ appear first – and then the rest of her snub-nosed red-haired self finally explodes into sight in a rush, after she has become secure enough to act spontaneously on her emotions, which inadvertedly cause Moominmamma to fall into a lake. The Nancy Lyman Huse essay contains a moving account of the therapeutic use of this story, within a group of abused children. Unconditional love can serve to conquer the fears that are an intrinsic part of childhood.

That sense of

tolerance seems finally, to be the overall point. The

creatures in Moominvalley qualify for acceptance with all of

their quirks, merely by dint of the fact that they exist. As

Lurie pointed out in her essay, one of the strengths of the

Moomin books is Jansson’s recognition that fear is as

strong a force in childhood as the absence or presence of

love. Physical threats such as floods, an onrushing comet

and all the other unpredictable dangers of life in

Moominvalley are conquered by the bonds of family, and by an

almost nonchalant air of inclusion. Set the table for one

more.

That sense of

tolerance seems finally, to be the overall point. The

creatures in Moominvalley qualify for acceptance with all of

their quirks, merely by dint of the fact that they exist. As

Lurie pointed out in her essay, one of the strengths of the

Moomin books is Jansson’s recognition that fear is as

strong a force in childhood as the absence or presence of

love. Physical threats such as floods, an onrushing comet

and all the other unpredictable dangers of life in

Moominvalley are conquered by the bonds of family, and by an

almost nonchalant air of inclusion. Set the table for one

more.

‘The warm, kindly, generous world of Tove Jansson is a world like our own,” Marcus Crouch wrote over 40 years ago, “yet strange, a world in which exciting things happen, perils are faced bravely, and at the end of every adventure there awaits Moominhouse and the calm, constant, loving kindness of Moominmamma. And always, there is the promise of another day.’ ENDS

For this

essay Gordon Campbell drew on quotes and commentary

contained in the Children’s Literature Review,

particularly the two essays by Nancy Lyman Huse. Shelley

Jackson’s obituary for Tove Jansson in the L.A. Weekly

(May 9, 2002) and Alison Lurie’s chapter on the Moomins in

her book Boys and Girls Forever (2003) were also valuable

sources.

Ian Powell: Postscript On Ethnic Cleansing, Genocide And New Zealand Recognition Of Palestine

Ian Powell: Postscript On Ethnic Cleansing, Genocide And New Zealand Recognition Of Palestine Gordon Campbell: On Why Leakers Are Essential To The Public Good

Gordon Campbell: On Why Leakers Are Essential To The Public Good Ramzy Baroud: Global Backlash - How The World Could Shift Israel's Gaza Strategy

Ramzy Baroud: Global Backlash - How The World Could Shift Israel's Gaza Strategy DC Harding: In The Spirit Of Natural Justice

DC Harding: In The Spirit Of Natural Justice Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Animal Encounters During Meditative States

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Animal Encounters During Meditative States Ian Powell: Gisborne Hospital Senior Doctors Strike Highlights Important Health System Issues

Ian Powell: Gisborne Hospital Senior Doctors Strike Highlights Important Health System Issues