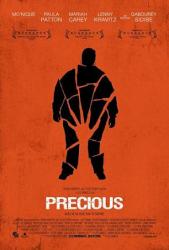

Film Review: None too Precious

None too Precious

What is one to make of this

extraordinarily gritty, brutal film by Lee Daniels? An

obese 16-year-old girl from Harlem is cooking for her

abusive, welfare-addicted mother in a room that rarely sees

the light of day. The mother hurls an object at her head,

knocking her out. In a world of the unconscious, her mind

strays: to boys she may never have, to fine clothes she will

not wear, to imaginary people who adore her. Poor precious,

enormous, molested Precious, played by Gabourey Sidibe.

Dreams are an escapist medicine, her manna, her opportunity

to fade into the forest dim. She is not allowed them too

often. She is cook, cleaner and welfare collector for her

mother in deeply squalid place.

What is one to make of this

extraordinarily gritty, brutal film by Lee Daniels? An

obese 16-year-old girl from Harlem is cooking for her

abusive, welfare-addicted mother in a room that rarely sees

the light of day. The mother hurls an object at her head,

knocking her out. In a world of the unconscious, her mind

strays: to boys she may never have, to fine clothes she will

not wear, to imaginary people who adore her. Poor precious,

enormous, molested Precious, played by Gabourey Sidibe.

Dreams are an escapist medicine, her manna, her opportunity

to fade into the forest dim. She is not allowed them too

often. She is cook, cleaner and welfare collector for her

mother in deeply squalid place.

One should not mention race, but the film demands it. At a time when the glow of Obama’s America would seem to demand ‘uplift’, Daniels has set about puncturing the ascent. He is portraying a system in tatters, a country in ruins. Abusive epithets are hurled by the mother as freely as objects against all and sundry. The characters abuse each other impulsively. Armond White, chairman of the New York Film Critics Circle, was troubled by those ‘brazenly racist clichés’ abundant in a ‘sociological horror show.’ White was brazen enough to equate Precious to The Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith’s cinematic, and racist epic from 1915.

A life dedicated to an abusive, vengeful mother, portrayed stunningly by Mo’Nique, with all the ennui of a Greek tragedy; a father who started to rape her when she was barely a few years old and gave her two children is potent subject matter for any audience. It is a film that manifests a stunning roughness, rubbing you as you leave the cinema. It cloys, it torments. The terrier-like determination of the mother to wound, to deceive, and to live, are astonishing. She hates the world, and does much to make others hate her. Education for her daughter is inconceivable and frightening.

The screenplay is compact and pointed. Between brutal moments, humour is allowed to bubble up, a fact that should not have escaped some of the critics. It shows that in the moments when there is no light, levity helps. Humour not only weakens human tyrants, but the tyranny of fate. In fact, Precious, based on Push, a novel by Ramona Lofton (‘Sapphire’), offers more hope than the novel that gave birth to it. Gaby Wood of The Observer (Dec 6) was astute enough to point out that girls in Precious’s position might well not have access to teachers, workers and friends. In giving birth, they might well not do so in hospital – most have no health insurance.

The teacher Blu is played by the elegant Paula Patton, who seems to retain her poise in the classroom of disturbed souls she so sturdily controls. The other girls who befriend Precious are a mixture of boastful confidence, crushing insecurities, dreams, viciousness and tarted-up confidence. They argue over the men they might love, the careers they dream about, the children they have, sometimes affectionately. But the huge, inadvertently charming Precious shall have her day, and the darkness, however vicious, is somewhat lessened.

Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land

Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death? Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing

Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing Gordon Campbell: On Aussie Election Aftershocks And Life Lessons

Gordon Campbell: On Aussie Election Aftershocks And Life Lessons