Scott Gilbert: Evolutionary Mechanisms & Knish

Scott Gilbert: Evolutionary Mechanisms & Knish

By Suzan Mazur

"[T]he developing organism is a remarkable phenomenon. It respires before it has lungs, digests before it has a mouth, and creates itself anew from ordinary matter. . . . Whereas the finished organism merely maintains its form, the embryo creates it." -- Scott Gilbert

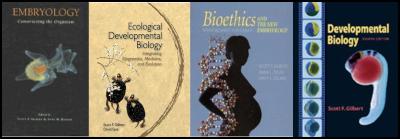

You’ve got to love the chutzpah of a scientist like Swarthmore biologist Scott F. Gilbert, who (along with his students) once wrote a feminist critique of fertilization narrative, as well as his joie de vivre “moonlighting” as a piano player in a Jewish “mariachi” band called Knish. Gilbert can deliver a lesson in evolutionary biology with the verve of Lenny Bernstein. It's no wonder his textbook Developmental Biology is in its 8th edition and printed in a dozen languages.

He is also on the nine-man Scientific Committee for the upcoming evolution conference in Rome hosted by the Pontifical Council for Culture, March 3-7, where he'll present a paper titled:

In 1893, Thomas Huxley, wrote, "Evolution is not a speculation but a fact; and it takes place by epigenesis." Note that evolution's chief defender did not complete his sentence with the phrase "natural selection," for Huxley was interested in the generation of the diversity needed for natural selection. That phase of evolution was regulated by development. Recent work has established five main mechanisms for the generation of anatomical diversity through changes in development, and this talk will review them and provide examples from the recent literature.

These mechanisms are:

(1) Heterochrony (changing the time or duration of developmental phenomena or gene expression)

(2) Heterotopy (changing the placement of developmental phenomena or the cell types in which a gene is expressed)

(3) Heterometry (changing the amount of gene expression in a manner sufficient to alter the phenotype)

(4) Heterotypy (changing the sequence of the gene being expressed during development)

(5) Heterocyberny (change in the "governance" of a trait from being environmentally induced to being genetically fixed)

These mechanisms have profound significance for how new traits can be generated, how they become integrated into developing organisms, and how they can become propagated through a population. It is argued that adding these developmental data and contexts provides a new and more complete theory of evolution, including a theory of body construction along with a theory of change.

Scott Gilbert is Howard A. Schneiderman Professor of Biology at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania where he teaches embryology, developmental genetics as well as the history of biology.

Gilbert has a BA in biology and religion from Wesleyan, an MA in the history of science from Johns Hopkins (under Donna Haraway) and PhD in pediatric genetics from Johns Hopkins (under Barbara Migeon). He is married to Anne Raunio, an obstetrician and gynecologist, with whom he edited the book Embryology: Constructing the Organism.

He is a fellow of the AAAS and the St. Petersburg Society of Naturalists and has served as chair of the Division of Developmental and Cell Biology of the Society for the Integration of Cell Biology.

Some of Gilbert’s awards include the Kowalevsky Prize in Evolutionary Developmental Biology, the Medal of Francois I from the College de France, a Guggenheim Foundation grant and an honorary doctorate from the University of Helsinki, among others.

He is currently investigating how the turtle forms its shell (ribs migrate to the dermis) with a grant from the National Science Foundation.

My recent phone conversation with Scott Gilbert follows.

Suzan Mazur : As you’ve said in your abstract for the upcoming Rome conference, evolution's chief defender Thomas Huxley noted that evolution takes place by epigenesis, and that diversity came before any natural selection could have. You present these main mechanisms for “generation of anatomical diversity”: heterochrony , heterotopy , heterometry , heterotypy and heterocyberny . Why has the scientific establishment and the mainstream media not really embraced these ideas?

Scott Gilbert : It’s hard to say whether the media has or not. The media's sources have to come from somewhere. That would be from evolutionary biology, from the scientists. Only recently has there been a cohort of evolutionary developmental biologists to answer reporters’ queries.

I think that scientific paradigms are slow to change. Many evolutionary biologists, especially those who were trained in the 1970s and 1980s, do not feel there is a need for a theory of body construction to go along with the theory of change they have -- which they think is a perfectly good one.

Evolutionary biologists have been very comfortable with the paradigm of the Modern Synthesis. The MS solves a lot of problems. It has modeled biology very well for the people who have asked it to model for them.

Given the limitations of the MS -- for which you need interbreeding species -- individuals with variations who can breed together, the program has worked remarkably well. However, with the MS the only way you could go to higher levels (above the species) was extrapolation.

What evolutionary biologists found was that evolution was predicated on mutation, recombination, and drift. It worked for what they were asking. Moreover, it made the extrapolation to higher levels possible.

Again, the notion that developmental evolutionary biology has is that you need a theory of body construction to supplement the Modern Synthesis, and then you could look at a theory of how to change body construction over time. You have to add developmental genetics to population genetics. This has been seen as unnecessary by many evolutionary biologists.

People like Ernst Mayr said this very explicitly. I quote him in the book I co-authored with David Epel, Ecological Developmental Biology. The publisher allowed me three historical appendices. One appendix is about how developmental biology was written out or ignored by evolutionary biologists.

Suzan Mazur : And then it became politically incorrect to question.

Scott Gilbert : Within its area it works. As long as evolutionary biology was defining itself this way, it had a beautiful model. The notion of natural selection in a breeding population works wonderfully. You add sexual selection to this. You add kin selection. You can take it in various directions. As long as there was a relatively parochial view of what evolution was and how it could be studied, the natural selection model and variation within a population worked really well. It was mathematical. It was based on mutations, which could be analyzed.

Suzan Mazur : But was it right?

Scott Gilbert : Was it right? For what it did, it was excellent . However, I’m on record in a 1996 paper saying that if the population genetics model of evolutionary biology isn’t revised by developmental genetics, it will be as relevant to biology as Newtonian physics is to current physics.

Suzan Mazur : Do you still hold to that statement?

Scott Gilbert : Yes.

Suzan Mazur : So has money been wasted in the research that’s been done?

Scott Gilbert : No. Not at all. I don’t think it’s been wasted.

Suzan Mazur : It could have been better spent.

Scott Gilbert : I think the priorities should now be changing, because until the 1990s we didn’t have a theory of body construction.

That’s the other thing. Evolutionary biologists in a way had every good reason to say we don’t need a theory of body construction, or a theory of change in body construction, because the embryologists didn’t have one.

One doesn't need a theory of body construction to talk about evolutionary change; but it becomes much richer when one has one. The thing that made it possible was DNA sequencing. This allowed us to compare genes between species, not merely within them. It showed that the genes involved in evolution were genes that are involved in constructing the body in the embryo.

Suzan Mazur : But why has the discourse been so sort of frat house -- animal house? Why has it come down to that kind of conversation when these ideas seem to all work together?

Scott Gilbert : I don’t know if I agree with you on frat house and animal house.

Suzan Mazur : Have you ever read PZ Myers?

Scott Gilbert : Okay. Yes. You’ll get his view and you’ll get Dawkins’ view. And you’ll get these people who have various agendas, and as you know all too well – science is done by people. No way of avoiding it. Thank goodness.

One has to show the data – and I think right now evolutionary developmental biologists do have a theory of the change in body construction. But before that you had to get certain things in place. You had to get proof of modularity in place, proof that changes in the enhancer regions can cause real selectable effects on morphology or on function. These things didn’t come easy. They came about in piecemeal fashion. There wasn’t coordination between laboratories.

The Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology formed the first evo-devo group in the year 2000. The first society for evolutionary-development in biology was established, I think, in 2006.

Suzan Mazur : Fairly recently.

Scott Gilbert : This is recent stuff. The first journals on evo-devo were also formed in the year 2000. So this is new. The coalescing of the field – sociologically speaking – is new. Yes, you can trace it back to the 1970s and how it’s come along, but it really didn’t gel until around 2000.

Suzan Mazur : But I find it peculiar that the two key evolution conferences have been organized outside the United States. One in Austria this last summer and the one in Rome in a couple of weeks. The day-long talks on evoutionary mechanisms at the Rome conference is extraordinary. Why is it the discussion taking place outside the United States? What statement is being made?

Scott Gilbert : What statement is being made? There have been conferences in the United States, but they’ve been generally smaller. There was a conference in 2001 at the SICB (Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology) meeting. It was the founding symposium for the evo-devo group at the SICB meeting.

There was actually one in 1991 at the American Society for Zoologists (the precursor of SICB). There were these smaller meetings. I think the one in 2001, which had international people in it, was in a way formative. The SICB meeting of 2001 brought American and European researchers together to talk. It also had a major historical component. Because, as you know, when you start a new field you have to go and find your forebearers and your heroes.

Suzan Mazur : Why didn’t the media pick up on this in a major way as a breakthrough in science?

Scott Gilbert : It’s a good question. The mainstream media does not attend the SICB meeting. The reporters from the scientific journals did write about it.The mainstream media to a large degree has a view of evolution that is Spencerian. One doesn’t have to go far in the media to see that. It was David Brooks, I guess, in a recent New York Times piece who said that evolutionary science has gotten rid of any idea of or any vestige of generosity or communality. It’s each for his own.

I think that the media has a competitive view of evolution, a very Spencerian and Hobbesian view. And they assume it’s the whole notion of Darwinism.

Suzan Mazur : Red in tooth and claw?

Scott Gilbert : Exactly. I think that when you have these meetings where scientists are talking about mechanisms of getting variation and evolutionary-developmental biology, even more so ecological-developmental evolutionary biology, which talks about symbiosis and all sorts of group selection mechanisms – this doesn’t fit into the media’s notion of what evolution is.

Suzan Mazur : What machine do you think is at play preventing the media from reporting this? Is it economy-related?

Scott Gilbert : I think most of the people in the media have never had a course in evolutionary biology. They are perpetuating the view of evolution that they themselves are receiving from society (not from scientists). If they were to take an exam on evolutionary biology, I think that they would not pass. Even those people who say they believe in evolution probably wouldn’t pass I don’t want to ask them why do you believe in evolution? What’s the data for it? Because they probably don’t know. If the scientists say it’s right, it’s right.

Suzan Mazur : What do you think is the significance of evolutionary mechanisms being central to the Rome evolution conference?

Scott Gilbert : I think that having the notion of evolutionary mechanisms gets around having to be tied down to one paradigm. They’re going fairly broadly. There are some things that are not being discussed. And other things that are. I think that in discussing the mechanisms, though, especially with the people who they have discussing the mechanisms, they are really casting a very wide net.

So that when you have people like Lynn Margulis talking about symbiosis and the origin of species, one hears a model of cooperation as opposed to a model of strict competition. When you have Stuart Kauffman and Stuart Newman talking about the physical antecedents and nongenetic evolution, you’re dealing with things that are not in the normal paradigm of competitive natural selection.

Now I’m sure that natural selection will be here. You have people like Doug Futuyma talking, who will be discussing natural selection. But in a way natural selection has been proven so often and so definitively, I don’t think it should be an issue. It’s like discussing – are skeletons made of bones?

Suzan Mazur : So you don’t agree that natural selection is more of a political term than anything else?

Scott Gilbert : I think natural selection occurs. And I think natural selection occurs within species. I don’t think natural selection alone can explain how butterflies got their wings or how the turtle got its shell. (For that, you need to know developmental biology, as well.) But I think that once you have variation within species, then natural selection can work.

Suzan Mazur : Do you think that natural selection should be relegated to a less important role in this whole discussion of evolution?

Scott Gilbert : Yes. I do. Natural selection has been touted by some scientists as the cause of variation. Here, however, I think development plays the major role.

But I’m not going to deny natural selection anymore than I would deny that friction is important in looking at the motion of objects in space – in our space anyway. Yes. It’s there. There’s natural selection. It works. And it works well within species.

To say that the fang of a rattlesnake evolved because of natural selection is absolutely correct, but also absolutely not sufficient. Because one has to say from what did the rattlesnake gets its poison fang? What modification of the salivary gland allowed it to be a poison gland? How did the change in development occur?

I had this argument with Michael Ruse. Michael Ruse and I had a wonderful exchange in Biological Theory. The fight that we had was over who were the heirs of Darwin. I think that’s what it comes down to. Ruse is basically saying the Neo-Darwinists are the sole heirs of Darwin.

Suzan Mazur : And you’re saying.

Scott Gilbert : I’m saying Darwin was an incredible guy who had all sorts of interests and that the evolutionary developmental biologists are actually asking a lot of the questions involving new species and how you get an adaptation that Darwin wrote about in his later books. On the Origin of Species was just his earliest book on this question, and then he dealt with variation and so forth in later books. In those books he realizes that natural selection is not enough.

Suzan Mazur : Well I think it’s disappointing that the media has been focused on celebrating Darwin’s birthday without a discussion of evolutionary mechanisms. Great to see that it’s being talked about in Rome.

Scott Gilbert : I share your disappointment. When I sent my dues in to the National Center for Science Education, and I received a book called Conceptual Issues In Evolutionary Biology, there was nothing about evo-devo in it. And I said, “Well, these aren’t the conceptual issues that grab me.”

I was also disappointed in the National Geographic article. National Geographic would have been the perfect place for a current piece on new ideas in evolution. They ran a two-page feature on the evolution of views on evolution in biology, starting with Darwin. And the last thing – the last thing they show is a set of embryos. The caption to the side of it says current interest in the changes of genes bringing about changes in body plans is now being studied. The embryo story should have been the focus.

In the book that David Epel and I just published, we quote David Quammen: "Nature interests me because it's beautiful, complex and robust. Evolutionary theory interests me because it explains why nature is beautiful, complex and robust." Evolutionary mechanisms are really wonderful to study, and they tell us a great deal about the origin and maintenance of our biodiversity.

Suzan Mazur : Editors of news organization and their owners really underestimate the intelligence of the audience. They think they have to be general about information because that’s all the public can grasp. People want detail. People want to know what’s happening. It’s a miscalculation. More newspapers would be sold if the story were really reported.

Scott Gilbert : They like the conflict theory. I found the Brooks’ article. It’s the February 18, 2007 David Brooks NYT column – and I’m quoting: “From the content of our genes and the lessons of evolutionary biology it has become apparent that nature is filled with competition and conflicts of interest.”

Suzan Mazur : Well he’s a vehicle of the economic status quo.

Scott Gilbert : Of the right. Yes. But I think that’s how evolution is taught. It comes around to what Huxley was saying about human nature, that we will use evolutionary biology to justify ourselves. And that in saying that nature is inherently amoral and self-interested – well, we’re just part of nature. We justify our doing evil things because we say our genes made us do it. Darwinian selection. We’ve been selected to be competitive bastards. We don’t usually hear about any other model, say, that we are the current pinnacle of the evolution towards cooperation.

Suzan Mazur : I think that some of this also has to do with so much of science being male- dominated. It’s interesting that Lynn Margulis takes this perspective of cooperation. There was also an astrobiologist, a woman, at the World Science Festival this past summer who talked about “flow” – and questioned why we always have to think in terms of modules.

Scott Gilbert : Have you read Donna Haraway’s book on this? Donna Haraway wrote a book called Primate Visions. It's about the gendered stories of primateology and how women have changed them. It's a beautiful book on how data is obtained and interpreted in a particularly important part of evolutionary biology, namely the ape-human interface. However, I wouldn’t say that females (or feminists) are necessarily soft nurturers and that males must be hard-core militarists. It doesn’t break down that easily.

I used to teach courses in feminist critique of science, and my students and I wrote a paper on feminist critiques of fertilization narrative, which was published back in the mid 1980s. I use feminist critique to show how some of our models of biology can be based on previously held models of human society.

In the fertilization narratives, the egg and sperm often become surrogates for women and men. (Remember the sperm sequence in Look Who’s Talking http://en.wikipediaorg/wiki/Look_Who's_Talking? The race of sperm and the female reproductive tract as passive conduit. Nothing can be further from the truth. No, that's a version of the old Hero Myth, where we are the descendents of the victor.

In actual fact, the female reproductive tract matures the sperm, and the first sperm getting to the egg do not fertilize it. Moreover, the egg activates the sperm before the sperm activates the egg. The egg is not the passive prize. But the public is told (repeatedly!) the story of conflict and prize winning.

Similarly, our models of nature often come from pre-existing models of society. Russian biologists (even before the Communist Revolution), for instance, criticized early views of natural selection as being too rooted in British mercantile capitalism. One needs to step outside the cultural narratives to see if we are basing our views of nature on social norms. That’s one of the reasons why international and humanities-based perspectives are important. They help stop science from becoming parochial.

But the important thing about scientific stories is that they are constrained by data. And that’s an important aspect of the Rome conference. The Intelligent Design people are not being invited, and I suspect that this is because their stories are not constrained by data. They can tell any story they like (and they do.) Even after being shown that their statements have been disproved many times, the ID people still continue to tell these false stories, because the public can’t tell if they are true or not. Scientists, however, have to limit their stories to that which the data allow.

Suzan Mazur

is the author of Altenberg 16: An Exposé of the

Evolution Industry. Her interest in

evolution began with a flight from Nairobi into Olduvai

Gorge to interview the late paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey.

Because of ideological struggles, the Kenyan-Tanzanian

border was closed, and Leakey was the only reason

authorities in Dar es Salaam agreed to give landing

clearance. The meeting followed discovery by Leakey and her

team of the 3.6 million-year-old hominid footprints at

Laetoli. Suzan Mazur's reports have since appeared in the

Financial Times, The Economist, Forbes, Newsday,

Philadelphia Inquirer, Archaeology, Connoisseur, Omni and

others, as well as on PBS, CBC and MBC. She has been a guest

on McLaughlin, Charlie Rose and various Fox Television News

programs. Email: sznmzr @

aol.com

Suzan Mazur

is the author of Altenberg 16: An Exposé of the

Evolution Industry. Her interest in

evolution began with a flight from Nairobi into Olduvai

Gorge to interview the late paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey.

Because of ideological struggles, the Kenyan-Tanzanian

border was closed, and Leakey was the only reason

authorities in Dar es Salaam agreed to give landing

clearance. The meeting followed discovery by Leakey and her

team of the 3.6 million-year-old hominid footprints at

Laetoli. Suzan Mazur's reports have since appeared in the

Financial Times, The Economist, Forbes, Newsday,

Philadelphia Inquirer, Archaeology, Connoisseur, Omni and

others, as well as on PBS, CBC and MBC. She has been a guest

on McLaughlin, Charlie Rose and various Fox Television News

programs. Email: sznmzr @

aol.com

Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance

Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land

Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death? Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One

Peter Dunne: Dunne's Weekly - A Government Backbencher's Lot Not Always A Happy One Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing

Richard S. Ehrlich: Cyber-Spying 'From Lhasa To London' & Tibet Flexing