New Zealand’s illegal trade in North Africa

New Zealand’s illegal trade in North Africa

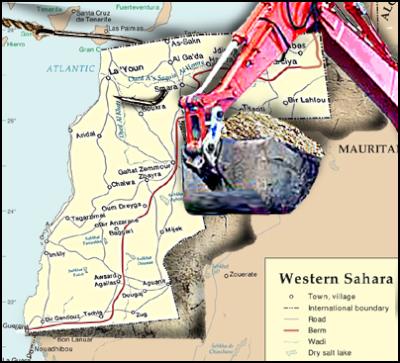

On May 25, a Turkish owned ship called the Cake is due at Lyttleton harbour, and similar port records show the same ship is due in Napier between 3-5 June. On both occasions, the Cake will be unloading a cargo of phosphates that originated in the Western Sahara region of North Africa. This is a highly dubious trade, in seeming violation of the UN Charter.

This is because

Western Sahara has been under military occupation by Morocco

since 1975, against the wishes of the indigenous Saharawi

people and of their UN recognized political representatives,

the Polisario Front.

The Saharawi have not taken

the theft of their country lightly. For 16 yerars from 1975

onwards, the Polisario Front waged a highly successful

guerrilla war against the dual invading forces of Morocco

and Mauritania, eventually forcing the latter out of the

territory. The UN finally brokered a ceasefire in 1991, on

terms that it would hold a referendum that would offer the

option of full independence.

Such a referendum has

been promised ever since Spain abandoned its colonial

territory in 1975, and unilaterally ( and illegally) handed

it over to Morocco and Mauritania. Even within the past ten

years, different versions of the same promise have been

made, by the UN and broken afresh.The UN for instance,

eventually appointed the US politician James Baker to devise

a compromise plan – which came down to five years of

autonomy under Moroccan rule, to be followed by a

referendum on full independence. Morocco has refused.

In the meantime, New Zealand has been engaged with

Morocco for nearly the past two decades in a highly

questionable trade in phosphate extracted from Western

Sahara. On its website, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and

Trade lists Morocco as New Zealand’s main source of

phosphates and fertilisers, and these natural resources made

up the vast bulk of our $167.9 million imports from Morocco

recorded in the year to June 2007.

Given how crucial

fertilisers are to NZ agriculture and farming’s role

within the national economy, the importance of this trade

can hardly be exaggerated. Unfortunately, trading in the

exploited resources of the Western Sahara is in violation of

UN resolutions on such non self governing territories as

Western Sahara, and of an explicit UN legal opinion. In

that respect the trade is not only morally reprehensible,

but is, in all likelihood, illegal under international

law.

Phosphate resources are only the half of it.

Under National and Labour governments, New Zealand has

sought to exploit Western Sahara’s rich fishing resources

as well. It signed a memorandum of understanding with

Morocco in November 2001 to facilitate the fisheries trade,

in the wake of a visit to Morocco by then Fisheries Minister

John Luxton in 1999, to discuss fishing opportunities for

New Zealand firms.

Two New Zealand firms, Sealord and

Prepared Foods NZ are currently exploring joint venture

fisheries deals in Morocco. Ravensdown and Ballance

Agri-Nutrients are the main New Zealand firms involved in

the phosphate trade. In January this year, Trade Minister

Phil Goff and Foreign Minister Winston Peters were in

Morocco, to discuss further trade options.

Ironically, this business activity makes Sealord -

which is half owned by Maori corporates - an economic ally

of the neo-colonial forces that have seized and settled the

territory, and it makes them an accomplice in exploiting

marine resources that ultimately belong to the indigenous

people of the Western Sahara.

The details of the

trade ? Sealord Spain, is a Sealord subsidiary, and has

joined with the Chilean company Friosur and Nippon Suisan of

Japan to form a partnership called Europacifico del Mar.

Europacifico distributes frozen fish products to Spain and

to Portugal. In addition, Europacifico exclusively

distributes some 30,000 tonnes of marine products in an

agreement with the Western Sahara-based Moroccan fishing

group Omnium Marocain de Peche.

As the

Norwegian-based Western Sahara Resource Watch ( WSRW)

research organization has discovered, this agreement entails

the distribution of some 30,000 tonnes of fish taken from

the occupied territory, mostly different species of octopus.

The bulk of the Saharawi population, WSRW has

concluded on the basis of its regular contacts, do not

profit at all from this exploitation. To compound

Sealord’s embarrassment, the agreements between foreign

fishing companies on one side and Moroccan fishermen

settlers on the other, are enabling Morocco to successfully

transplant its own fishing communities to Western Sahara,

thus leading to the further displacement and detriment of

the indigenous people.

On April 28, Boudjema

Souilah, head of the Foreign Affairs wing of Algeri’a

National Council warned countries that co-operate with

Morocco, “to stop plundering the natural resources of

Western Sahara.” New Zealand’s collusion with the

Moroccan regime happens to be surfacing right in the middle

of the latest round of UN brokered talks intended to try and

resolve the thirty year long impasse.

No one is

holding their breath for the outcome. Earlier this month in

Manhasset, New York, representatives of Morocco and the

Polisario Front met under the UN’s auspices in the fourth

round of the latest set of negotiations, Morocco is offering

broad autonomy to a Western Sahara that would still leave

its peoples and resources under Moroccan control, while

Polisario are holding out for a referendum containing the

option of full independence. Full independence, the UN’s

Envoy for the Sahara Peter Van Walsum said in late April,

is ‘unrealistic. ”

The UN’s view of Western

Sahara Trade.

Is the NZ trade in Western

Saharan resources legal ? Phil Goff says it is. On 26 July

2006, Goff told Parliament he had been advised that New

Zealand companies involved in the phosphate trade “are not

in breach of either international or domestic law in

importing phosphate from Morocco that has been mined in

Western Sahara. “ Furthermore : “ I am also advised

there are there are no legal grounds for banning the trade

from Morocco. Indeed, to do so would be subject to a legal

challenge from Morocco under international trade law.”

Earler this month when the details of the Sealord deal

emerged Goff said that the UN’s position was that such

trade was legal, so long as the people of the territory

benefitted.

Virtually in the same breath, Goff voiced

his concerns about the political situation in the territory

and said New Zealand has “strongly supported” the UN

processes and peace plan designed to resolve the Western

Sahara dispute.

How Goff could reach those

conclusions is a mystery. His claims misrepresent the

analysis provided to the Security Council on 29 January 2002

by the UN’s legal counsel, Hans Corell. Corell had been

asked by the Security Council to advise on the legality

under international law of ‘the offering and signing’ of

contracts with foreign companies for the exploration of

mineral resources in Western Sahara.”

Corell’s

analysis ? For starters, Corell

confirmed that Western Sahara was a non self governing

territory as defined by the UN, that its peoples’

interests were paramount, and that Morocco had no valid

administrative power over it. Morocco, he pointed out, was

not listed by the UN as Western Sahara’s administrating

power - and had never transmitted to the UN the necessary

information on social, economic and educational conditions

in the territory as required of any such valid

administrating power under the UN Charter.

Furthermore, Corell reminded his readers that “the General Assembly has consistently condemned the exploitation and plundering of natural resources and any economic activities which are detrimental to the interests of peoples of these territories and which deprive them of their legitimate rights over their natural resource.”

Exploration that went only so far as reconnaissance

and evaluation, Corell continued, wasn’t illegal per se.

Nor would – and this is the bit Goff has selectively

seized upon - actual exploitation be illegal if it accorded

with the wishes and interests of the people of Western

Sahara. In this case however, Morocco is the beneficiary,

not the Saharawi. Furthermore – and this should be the

decisive factor for Goff - the Saharawi have not been

consulted about how they feel about the exploration and

exploitation taking place. By contrast, Corell cites in his

opinion how when it came to agreements on the exploration

and exploitation of oil and gas deposits in East Timor,

consultation was carried out with the East Timorese people,

who participated actively in the discussions.

This

kind of conulstation has simpolyt not happened in Western

Sahara. Exploring its resources without consent would not,

in itself, in Corell’s view, be illegal. The crunch point

would come when the actual exploitation occurred. “If

further exploration and exploitation were to proceed in

disregard of the interests and wishes of the people of

Western Sahara, they would be in violation of the

international law principles applicable to mineral [ read :

phosphates, or fisheries] resource activities in non self

governing territories.”

This situation could hardly

be more clear. Yet Goff, in his 26 July 2006 statements to

the House and subsequently, has kept on trying to find

wiggle room in the Corell opinion where none exists : “ I

do not think anybody can say with any certainty what the

local people in Western Sahara feel about the mining of

phosphate resources. I certainly have no evidence about

that. I am aware that the independence movement [ ie, the

Polisario Front] is opposed to that, but I am not aware of

what the views of the ordinary people in Western Sahara may

be, and how could I be? “

This is incredible stuff.

Goff is claiming that we don’t know what the people of

Western Sahara think of the trade - even though in the same

breath he says he knows that their recognized political

representatives ( ie the Polisario Front ) oppose such

trade. Polisario, you will recall, are the organisation the

UN continue to recognize as the valid political voice of the

Saharawi people in the Manhasset talks aimed at resolving

the conflict.

That’s not good enough for Goff. In

the House in 2006 , he was adamant that no way exists for

him to know what the Western Saharans really want. That’s

why, he says, he has to keep on fostering and supporting

the phosphate trade with Morocco. Ironic, really – with

such sophistry, Goff is siding with the very people who

have consistently denied the Western Saharans the right to

say what they want, via a referendum on self determination.

If Goff feels in such hapless confusion about what

Western Saharans really feel about the foreigners and

Moroccans jointly exploiting their natural resources, one

can reasonably ask what steps did Goff and Winston Peters

take during their January 2008 visit to meet with Saharawi

leaders, in order to dispel New Zealand’s economically

convenient state of confusion?

Need I also point out

how craven it is for New Zealand to be invoking the fear of

being sued by Morocco for a WTO trade violation, if we ever

did ban the phosphate trade from Western Sahara? In

reality, New Zealand would be doing the world a service if

it did impose such a ban, and dared Morocco to challenge it.

To win any subsequent WTO complaint, Morocco would

have to prove its rightful ownership of the resources

involved. To do so, it would have to argue that its military

seizure and subsequent colonization of Western Sahara was

valid, and that Morocco was the proper administrating

authority. It has absolutely no chance of doing so. The

Corell opinion and the International Court of Justice in its

1974 Advisory Opinion have both come down heavily on the

side of the Saharawi.

To this day, Morocco claims

that legal ties of allegiance existed in pre-colonial times

between the Sultan of Morocco and the tribes living in the

territory, sufficient to validate its seizure and current

occupation. The International Court of Justice shot that

claim down in 1974. Some tribes, the Court agreed, did have

such ties at the time when the Spanish arrived in 1884, and

some others in the territory did not.

Overall, the

Court concluded the evidence before it did not establish

“any tie of territorial sovereignty between the territory

of Western Sahara and the kingdom of Morocco…”

Therefore, it found, the central UN resolution 1514 on

de-colonisation did apply to the people of Western Sahara.

In particular, the Court supported their right of

self-determination “through the free and genuine

expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory.”

So, despite the Clark government’s vociferous

support for the UN and its principles, our comp;licity in

the economic exploitation of the Western Sahara suggests the

opposite. For now, and unlike its stance on East Timor, New

Zealand prefers to cut deals with the occupying power that

has long been denying the right of Africa’s last colony to

full self determination under the UN Charter.

Where To From Here?

The need to find a speedy and just solution in Western Sahara could hardly be more pressing. For the last 30 years, some 90-165,000 Saharawi refugees who fled the Moroccan invasion have been living in horrendous conditions in camps ( situated in harsh desert regions inside Algeria ) that are controlled by the Polisario Front. The Polisario leadership does not live inside the camps, but controls freedom of movement from them, and dissent within them. There are recurring reports that the Polisario leadership profits from smuggling some of the international humanitarian aid essential to keeping the camps afloat.

Both Morocco and the Polisario Front

leadership have been accused of too readily accepting the

continuation of the status quo. Any final resolution of

Western Sahara’s struggle for freedom, as the al-Hayat

newspaper wrote in late April, will really depend on

whether Algeria and Morocco - the two big rivals for

supremacy in this part of North Africa - can reach a

mutually acceptable compromise.

This will not be

easy. Algeria and Morocco co-exist in a climate of mutual

suspicion and paranoia that has twice led to outbreaks of

military conflict in recent times. First, in the so called

Sand War of `1963, and again in 1975, when Algeria came off

badly. Algeria and Morocco differ in very essential ways.

The current state of Algeria was born from a revolutionary

struggle against its colonial power, France and has natural

sympathy for the Saharawi quest for independence. Morocco by

contrast is a hereditary kingdom that can trace its

existence in consistent form right back to the 9th century.

Morocco assisted the Algerians in their revolution, and

feels betrayed by them..

Algeria on the other hand,

distrusts Morocco’s ambition to re-create the vast

Greater Morocco borders of pre-colonial times. Therefore, it

uses the Polisario as a pawn and buffer against further

expansion by Morocco. For its part, Morocco fears that a

free Western Sahara would place an Algerian client state

right up against its own borders.

And so the wary,

paranoid dance continues - however tantalizing the fruits of

a lasting resolution might seem. If Western Sahara did ever

become independent, Algeria could use its former client for

direct access o the Atlantic, and use the same route to

export iron ore from the Gara Djibilet deposit situated on

the Algerian border with Western Sahara. Oh, and did I

mention that there is a very real prospect of large reserves

of oil and natural gas being discovered in Western Sahara?

Morocco has its eye on that potential bonanza. For

now, it is gambling that its occupation is being accepted

as a fait accompli – by France, by the United States and

apparently, even by the likes of New Zealand. The risks

involved with the world choosing that route and shelving a

just resolution is as real with the Saharawi as it is with

the Palestinians. Young Saharawi refugees who have spent

their entire lives in the camps are increasingly restive

with the stalled diplomatic process, with the corruption

among the Polisario, and with the failure of the UN to keep

its promises. Reportedly, they want to go back to fighting.

If they do, and Morocco responds militarily by say,

shelling the camps on Algerian soil, the Algerians would

have no choice but to respond in kind. This would trigger a

regional war in North Africa that could make Lebanon look

like a picnic. Besides everything else, any rise in regional

tension could well leave New Zealand farmers needing to

look elsewhere for a cheap supplier to satisfy their

fertilizer addiction.

Over coming days and weeks, I

will be seeking comment from Phil Goff, and the likes of

Sealord and Ravensdown about this phosphate/fisheries trade

with Morocco. Not to mention comment from the trade

unionists who will be unloading those phosphate cargoes from

the Cake, in Lyttleton and in Napier.

ENDS

Gordon Campbell: On The Making Of King Donald

Gordon Campbell: On The Making Of King Donald Binoy Kampmark: Rogue States And Thought Crimes - Israel Strikes Iran

Binoy Kampmark: Rogue States And Thought Crimes - Israel Strikes Iran Eugene Doyle: The West’s War On Iran

Eugene Doyle: The West’s War On Iran Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia

Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal

Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal