Gordon Campbell: Zaoui’s beliefs

Gordon Campbell: Zaoui’s beliefs - a

vision of Islamic modernism

OK, so you’re a pacifist who believes that killing is never justified, someone once asked Joan Baez. But what if you and the kids were driving in a car at speed around the corner on a narrow mountain road, and what if an old lady who couldn’t get out of the way was slap there in front of you ? Wouldn’t it be OK then to take one life for the greater good ? What would she do as a pacifist in that situation, huh ? “Oh, I’d probably just scream, drive over granny and swerve off the cliff, kids and all,” Baez replied.

Point being, its pretty hard to predict how anyone is going to react, even when you think you know the values and ideals they profess. That’s one of the main difficulties I have with the Ahmed Zaoui review that began earlier this week. Behind closed doors, the SIS get to pretend they can predict the future risk to New Zealand posed by someone they’ve barely met – and do it so accurately, they’re willing to wager his life on the outcome.

Of course, some would say it’s a wager either way – it’s his life if we deport him and maybe our lives if he’s allowed to stay. I think that’s why we all have some obligation to get our heads around this case. Because if we send Zaoui back to torture and death, it will be being done in our name.

On the other hand, we also need to feel pretty sure we can sleep safe in our beds if we let him stay. That’s one reason why it’s been so infuriating that the bureaucrats have shut the public and the media right out of the SIS Inspector-General’s review of the evidence, and even from the sessions that deal only with information already in the public domain. This review could have been our best chance yet to form our own judgements about the stranger in our midst.

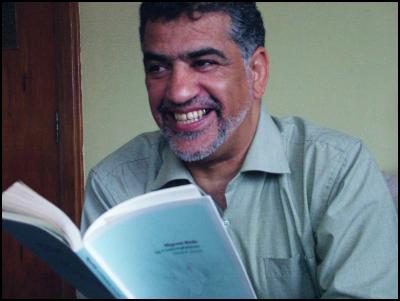

I’m not going to claim this account here can make up for it. Over the last five years though, the Zaoui case has been conducted as a clash of stereotypes – Muslim terrorist threat versus plaster saint. To talkback radio, Zaoui is barely human and a waste of time and money. At the other end of the spectrum, his supporters have presented Zaoui in a variety of lights – man of peace, poet, lecturer, family man, prisoner, ping pong player, cook, theologian, and soccer coach – in the hope that one or more will humanise him to the wider public.

Unfortunately, the saga has been enacted without a context. Only Alex Van Wel’s TV1 documentary a couple of years ago took the trouble to go back to Zaoui’s home country and convey that this is really an Algerian story – and that Zaoui’s odyssey over the past 15 years has been part of the wider Algerian tragedy. So it needs to be understood in the light of Algeria’s history and values, and not as some sideshow to 9/11 and Bin Laden. If we are ever to know if Zaoui poses a threat, we need to know more about how, at 47, he sees the world and the role that remains for him within it.

Where to start ? Yesterday I mentioned the Algerian social theorist and journalist Malek Bennabi as a key influence on Zaoui, but got Bennabi’s birthdate wrong. Bad start. He was born in 1905, not 1907 – and died in 1973. His influence on an entire generation of Algerian politicians and intellectuals has been immense.

Only last month, the Cambridge University scholar Sebastian Walsh described in the Journal of North African Studies how Bennabi ‘s attempt to reconcile Algerian nationalism with Islam had made a lasting impact on the Front Islamique du Salut ( or FIS) political party to which Zaoui belongs. Especially upon the FIS intellectuals from Algiers University – which again, was Zaoui’s milieu.

Bennabi’s life work was to promote a form of Islamic democracy grounded in Algerian values and history. His work stands consciously apart and consistently opposed to the pan-Islamic radicalism of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, which became the wellspring of jihadism and the Wahhabi extremism of Bin Laden. It is no accident that Bin Laden’s deputy is the Egyptian doctor, Ayman Zawahiri.

Throughout the 1960s, Bennabi was the central figure in al-Qiyam - an Islamist organization opposed to both the socialist nationalism of the 1960s post revolutionary era, and to what Bennabi disparagingly called the Salafists. The Salafists were the ‘pure ones’ who rejected progress, shunned modernity and urged the faithful to return to the strictness that they discerned in the Prophet’s epoch. Three decades later, the Salafist tendency inspired the extremes of the GIA and the GSPC terrorist groups to which the SIS is now hellbent on linking Zaoui.

That seems totally wrong-headed. Bennabi and his disciples always stood in strong opposition to the Salafists, the Muslim Brotherhood, and to its Egyptian ideologue, Sayyid Qutb - who was Bin Laden’s acknowledged guru.

My point being : that when you consider Zaoui’s intellectual lineage and that of his closest colleagues in the FIS in Algerian terms, you don’t end up in Bin Laden’s neck of the woods – you arrive back at Bennabi, a modernist, who could hardly have been more alien to the spirit of jihadism, Walsh, in his North African Studies article puts it this way : “

The Algerian army’s justification of the 1991 coup, that if the FIS won it would cancel future democratic elections, seriously misrepresented the nature of the organization, the roots of which lay in Bennabi’s Islamic nationalism rather than the pan-Islamism of the Muslim Botherhood. In tacitly accepting this justification, Western governments may have allowed a chance for the development of genuinely liberal governance, compatible with an Islamist framework, to be extinguished.”

Zaoui in other words, is not the vanguard figure of revolutionary Islam. If anything, he is the fag end of Algeria’s lost chance for Islamic modernisation. New Zealand should know a lot more about this than it does. It is one of the ironies of the post 9/11 world that the world’s leading authority for the past 20 years on Qutb – the godfather and ideologue of jihadi terrorism – is living in Christchurch. Namely, William Shepperd, emeritus professor of religion at Canterbury University. Shepperd’s knowledge of Qutb’s life and works should be being treated as a national treasure by the media, in particular.

Zaoui, in the few conversations I’ve had with him, has always expressed horror at Qutb’s appeal within the Muslim world, and especially to the young. Bennabi was definitely Zaoui’s man, because both were and are, religious and social moderates. In 1994, Zaoui helped organize the so called “Rome Platform” peace conference that aimed to broker a solution to the Algerian crisis, and entailed Zaoui working in unison with the San Egidio Catholic community in Rome. In fact, Zaoui had only been wooed into joining the FIS by people that he had known at the University of Algiers, in an effort to lend the party greater moral authority and spiritual coherence. “I won’t say I opposed the FIS,”

Zaoui told me in a prison interview for the Listener in late 1994, “ but I had no interest in politics at the time. Academic work attracted me more. And I had been doing social work [connected to the mosque] with the people in my area.”

Not that he was exactly a political ingénue. As I mentioned in that Listener article, Zaoui had not been immune to the politics of the streets. During the 1980s, he was picked up and tortured by Algerian security forces, and still has scars on his body from the experience. Not that this experience – or Bennabi’s influence – can be taken as an absolute determinant of his, or anyone’s, subsequent behaviour. Mohammad Said, a colleague of Zaoui both at Algiers university and within the FIS, ultimately went over to GIA in an attempt to rein them in within a unified grouping of opposition groups, and paid for it by being killed by the GIA leader, Djamel Zitouni.

The relevant point here – for my five cents worth, anyway - is that Zaoui’s potential risk in future cannot be understood by looking at him and his actions backwards, through the lens of 9/11 and global jihad. The context is Algerian, and during the mid 90s even the Clinton administration were sending out positive signals to the FIS, as the moderate alternative. Even after Zaoui went into exile, the likes of US deputy secretary of State Mark Parris were making a clear policy distinction between the Islamic fundamentalists in Algeria, and the FIS leadership group to which Zaoui belonged in Europe.

In an April 1994 speech, Parris noted that “ There is no evidence indicating that the FIS leadership abroad is currently in any way controlling the activities of those groups who have claimed responsibility for the [terrorist] acts referred to.” The US policy aim at the time that was being articulated in various speeches by Parris and other Clinton officials ( Anthony Lake, Robert Pelletreau, Edward Djerejian and finally by Clinton himself) was to encourage and promote the moderates ( ie the likes of Zaoui within the wide church of the FIS leadership ) and to isolate the extremists. The assumption was that the Algerian junta would ultimately need to negotiate with the FIS and work out with a new basis for co-existence and power sharing. It didn’t turn out that way.

Like Bennabi’s optimism, Zaoui may now – thanks to his 15 years in exile - be out of sync with the political realities that now exist in Algeria. People there are worn out by the years of civil war. Hopes and options seem far more narrow. Bennabi by contrast, was writing in the 1960s in an idealistic Algeria that had just won its independence, and was unmarred yet by the carnage to come in the 1990s.

Democracy, Bennabi believed, could not be imposed or imported. It needed to include and recognize all dimensions of Algerian society, rural minorities and urban elites alike. Democracy was to be regarded as a culture, a virtue – not just a voting process – and it would evolve in a three-stage process. We realise God in ourselves, Bennabi wrote, we see Him in others, and then we act accordingly in social and political space.

The necessary conditions for democracy could only be fostered through education and experience – and Bennabi invoked all the Koranic verses that support free speech, women’s rights and minority rights to make that point. Unless people can realise democracy in their own hearts and local communities, he believed, Islamic democracy would never succeed in avoiding the forms of exploitation commonly found among democratic Western societies organised by the values of secular humanism. As he once pointed out: “An order that bestows a ballot and allows a man to starve is not a democratic order.” It does sound sound so very 1960s, and utopian. Still, it isn’t a bad three step charter for living a moral life : self-respect, mutual respect, respect for God. Surely, even the SIS can’t concoct a case for deportation out of that line of thinking.

Next Monday: Security paranoia, in the post 9/11 world

Disclosure : Gordon Campbell now

works as a media officer for the Green Party. He has been

writing about the Ahmed Zaoui case since 2003.

Disclosure : Gordon Campbell now

works as a media officer for the Green Party. He has been

writing about the Ahmed Zaoui case since 2003.

ENDS

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal

Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest

Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels

Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels Keith Rankin: Remembering New Zealand's Missing Tragedy

Keith Rankin: Remembering New Zealand's Missing Tragedy Gordon Campbell: On Why The Regulatory Standards Bill Should Be Dumped

Gordon Campbell: On Why The Regulatory Standards Bill Should Be Dumped