Mark Levey: The History of Political Dirty-Tricks

The History of Political Dirty-Tricks: (Pt 2) How to Colonize a Larger Country

by: Mark G. Levey

Abstract - Part I of this series introduced the Okhrana, the Czar's secret police, and its role in creating political instability across Europe that supported manipulation of financial markets in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. This set the mould for modern intelligence agencies in roiling markets, toppling regimes (often their own), and provoking wars.Part II, below, goes to the origin of the Okhrana as the palace guard of the Germanized nobility in 18th century St. Petersburg. It traces the Okhrana's role in the royal assassinations that made Russia increasingly a giant vassal of Prussia, and how the Czar's court and its secret agents developed the modern techniques of state terrorism that spread worldwide in the 20th Century. The next installment details how exiled Okhrana officers were recruited into western intelligence and security police following the 1917 Revolution.

II. GUARD AGAINST REVOLUTION AND REFORM (1696-1917)

Since the 17th Century, the mission of the Czar's Imperial guard (Okhrana, literally "Guard", or okranoe, meaning "security") was to hunt down and stamp out opponents of autocratic rule in Russia. They also acted as the court police at St. Petersburg, having a hand in the slayings of nobles that marked transitions of dynastic power. The Okhrana did this with a particular ruthlessness and stealth, often secretly controlling the most violent revolutionary terrorists they claimed to be guarding against. By the early 20th Century, the Okhrana had developed a vast, covert network across the Russian empire and in major cities around the world.1

From St. Petersburg to Paris to New York City -- anywhere there was a large Russian emigre community or a potential political threat to the Czar -- the Okhrana carried out a ruthless campaign of assassinations, kidnappings, forgeries, frame-ups, and high-level penetration of revolutionary and reformist movements. Since its reorganizations in the 1860s under Nicholas I, and again in 1881 under Alexander III, the Okhrana also pursued foreign espionage activities as an auxiliary to the traditional intelligence-gathering function of the Russian diplomatic corps and military intelligence.2

Okhrana officers were selected from the officer corps of the Imperial Army. They were uniformly the sons of the Russian aristocracy, chosen for theirloyalty to the monarch, piety to the Orthodox state religion, and personal attachment to the system of feudal caste privileges that persisted in Russia long after most western European states had become secular republics or constitutional monarchies. While some were well-educated and widely-travelled, many of the Okhrana rank-and-file officers still held that the Czar had a divinely-given right to perpetual rule. Their fervor was driven by the notion that Moscow was the "Third Rome" and only true repository of the Christian faith, following the fall of Rome and Constantinople. Okhrana was thus a religious-military order, akin to the Knights of Malta,3 that had survived into the 20th Century.

Policing the Eastern Palace: (1696-1801)

The Okhrana were created as the personal guard of Czar Peter I ("Peter the Great", r. 1696-1725). As the first Russian leader to travel to the west, Peter I brought the Okhrana into contact with the contemporary secret services of Prussia, England, Holland and the Holy Roman Empire, each of which had their own hoary traditions of political policing, palace intrigue, assassination and espionage.

Across Europe at the time, political and religious assassination of foreign and domestic opponents was commonplace. It was not until later in the 18th century, according to Ward Thomas, that assassination ceased to be a legitimate tool of war, and only then did immunity arise as a general prohibition against killing foreign heads of state while the pace of domestic assassination may have actually increased.4 Thomas writes:

Phillip II of Spain, who played a major role in the Catholic Counter-Reformation, was an enthusiastic advocate of the assassination of Protestant leaders, placing a price on the head of William of Orange, the leader of Holland (who was in fact murdered in 1584), and sponsored several plots to kill Queen Elizabeth I of England. During the 1570s and 1580s alone, Elizabeth was the subject of at least twenty assassination plots supported by foreign powers, and herself employed assassins in Ireland.5

Peter and his travelling entourage could not help but have noted the instrumental role of Sir Francis Walsingham's anti-Catholic spy service, and its skillful use of assassination, forgery, and treachery in maintaining Elizabeth I on the throne of England. Before Peter's arrival in England, Walsingham had concocted evidence to arrest Elizabeth's Catholic half-sister, Mary Queen of Scots, who had an equal claim to the throne. Pretext being duly found, Mary was put to death in the Tower of London. Of course, the Russians were themselves no strangers to political complexity. After all, they had inherited the legacy of Byzantium, the "Rome of the East", along with its religion, alphabet, and the two-headed eagle motif of a political culture that lent its name to court intrigue.

In his travels across western Europe, the Czar of Russia would also observe how the English and the Dutch crowns, alike, had issued royal charters to private companies, and how these "free booters" were effectively used to attack Spanish holdings and shipping in the New World while preserving plausible deniability for their governments.

Upon his return, Peter the Great pursued aggressive military expansion supported by a program of reform from above. Some of his modernizing measures were controversial, particularly the state's annexation of the Orthodox Church and compulsory national service for the nobility. In the last year of Peter's rule, he killed his only son, Aleksey, who had plotted with a group of reactionary nobles who sought to reverse Peter's program. Deprived of a natural heir to the Romanov throne, the dynasty entered into a period of unstable succession, marked by "intrigues, plots, coups, and countercoups", the outcome of which was decided by the elite palace guard in St. Petersburg.

This period of opening to the west and political chaos in Russia coincided with the frequent intermarriage of the old Muskovy nobility with the aristocracy of neighboring Prussia. As a result, by 1762, Russia had become Prussia's de facto eastern colony. Czar Peter III, whose reign was cut short after just six months on the throne, was to be the last male scion of the Romanov dynasty. His assassination that year ended the reign of the Muskovites, who had ruled Russia since the mid-1500s.6

The Romanov absorption into the Prussian aristocracy increasingly Germanized the Russian royals and the country's foreign policy. Peter III, whose father was a Prussian Duke, inherited the Russian crown in the midst of the Seven Years War between Britain and France, with Russia allied with France. Thus, the Russian armies found themselves facing Prussia, Britain's ally at the time. The Russians fought to the gates of Berlin in 1760. The newly installed Czar, a self-identified German and Lutheran, facing the jaws of victory, promptly sued for peace and withdrew his troops without forcing any meaningful concessions out of the Prussian Emperor, Fredrick the Great. This was an unpopular move for Peter III in the palace, among the Russian people, and was particularly resented in the ranks of his army.

The Czar added further insult to the wounded pride of his generals when he ordered that henceforth the Russian officer corps would affect Prussian-style uniforms and submit to Prussian military drill. This was far too close to a public admission of Prussia's de facto annexation of Russia, and of the true allegiance of Peter III. Czar Peter III was assassinated by the Okhrana on June 28, 1762. The throne was then handed to his wife, Catherine II, who wisely adopted protective coloration of Russian nationalism and the Orthodox faith.7

Catherine II ("Catherine the Great", ne., Sophia Augusta Petrovna), daughter of Prince Christian August of Anhalt-Zerbst, a principality in East Prussia, and of Princess Joanna Elizabeth of Holstein-Gottorp, a powerful German Pomeranian clan, became Empress of All Russia. All the Czars and Czarinas that followed her were German and Baltic nobles, not the old Russian tartar and Muskovy stock.

Catherine the Great is remembered primarily for her good taste in Art and for her great wealth which she spent lavishly to acquire it. With a good instinct for public relations, she publicly adopted Russian mannerisms and the Orthodox religion, Catherine actually conducted herself like a French noble, affecting much of the rhetoric of the French Enlightnment. However, she was no democrat. During her own 30 years as Russia's ruler, she increased the crown's burdens on the the nobles and multiplied the numbers of Russian serfs and state vassals, greatly enriching herself and her circle in the process.

With his ascension as Czar in 1796, Catherine the Great's son, Paul, eased conditions for the serfs while further restricting the privileges of the Russian nobility. For his efforts as a social reformer, he was stangled in his sleep the night of March 12, 1801 at the hands of an aristocratic cabal led by Count Pahlen, head of the palace guard.8

Policing the Reformers (1801-1881)

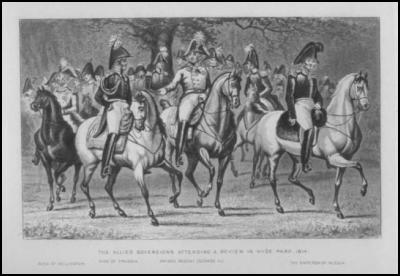

After Paul's assassination, his eldest son, Alexander I, took the two-headed throne. Alexander had been groomed as Catherine's successor, thus his reign was marked by a continuity of Catherine's program of tight control over the population and as a period of relative order in the palace. He was lauded by his fellow nobles as the "Savior of Europe" after Russian forces (and the Russian winter) chased Napolean's army back to the gates of Paris. However, the situation for the average Russian grew more desperate. By 1800, Russia was a vast feudal estate with millions of slave-like serfs ruled by a tiny circle of noble families intermarried with the Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp dynasty in the distant Prussian kingdom.

In the west, this was a period of hard-fought democratization and modernization. Prospects for constitutional government were set back in Russia with the bloody suppression of the "Decembrist" reform movement in 1825. Alexander's death in November of that year presented an opportunity for supporters of constitutional reform to overthrow the monarchy. The coup failed, and instead of a republic, the coronation of Nicholas I brought further repression. The Czar's palace guard executed, jailed, silenced, or chased into exile many leading Russian nationalists, the country's most enlightened aristocrats, and much of its intelligentsia.

Having put down the constitutional movement in Russia, Czar Nicholas I (r. 1825-1855) set to work creating the 19th century prototype for the authoritarian police state. Administration of the palace guard was made a bureaucracy, lodged with the Interior Ministry. As the so-called Third Section, the Okhrana was greatly expanded during Nicholas' reign so that it could efficiently administer the apparatus of a modern police state, including a huge network of spies, along with "censorship, and other controls over education, publishing, and all manifestations of public life".9

Not content to restrict his program of "autocracy, Orthodoxy, and nationality" to Russia, Nicholas unleashed the Third Section and the Imperial Army to pursue radicals across Europe. When popular uprisings broke out in European capitols in 1830, and again in March 1848, Nicholas offered his army and secret service to suppress democratic insurrection across the continent. On hearing of the abdication of King Louis Philippe of France, Nicholas roared to his Guard, "Gentlemen, saddle your horses. France is a republic!"10 The Russian Czar's offer of intervention was "accepted in some instances, earned him the label of gendarme of Europe".11

Capitalizing on the manifold ethnic, religious and political divisions in the constitutionalist movement in various countries, the "old internationally-minded aristocracy" held a great advantage over the nationalist reformers. The royals and upper class landed gentry "furnished the bulk of officers in the armies"12 commanding a largely apolitical peasant mass in the ranks. The Czar and his kin in the royal houses of Austria and Prussia thus retained firm control over their armies to destroy the fledgling democratic national assemblies in central and eastern Europe.

After successfully crushing the 1848 constitutionalist revolution in Austria-Hungary on behalf of the Habsburgs, Nicholas pursuaded Prussian Emperor Frederick William IV to refuse to submit to the newly established National Assembly in Frankfurt. Emboldened, the Prussian army marched into Berlin and Frankfurt, and stamped out the fledgling republic.

Return of the Prussian Policeman

While armies are essential to the maintenance of autocracy, the preservation of dynastic rule and the prevention of democracy requires an effective secret police. The suppression of its middle-class constitutionalists was followed by the expansion of the Prussian political police under Karl Ludwig Friedrich von Hinckeldey.

Appointed police president of Berlin in late 1848, Hinckeldey was an innovator of many of the features of modern systematic political policing. Among the tactics that he introduced with his new police system in Berlin was the "Litfass columns". Named for Ernst Litfass, Frederick William's court printer, he had dozens of these large poles erected in strategic spots around Berlin. The public posting of political notices was then banned. By application to a state office for a waiver, however, the columns could be used to display messages. The police dutifully recorded the names of all who had applied. A. Richie, Faust's Metropolis: A History of Berlin, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1998 at p.134.

LEGACY OF THE LITFASS COLUMNS: A similar ploy was later adopted by the People's Republic of China. In the mid-1980s, the Communist authorities at first appear to tolerate the operation of a so-called Democracy Wall, where "dissidents" in Beijing could post political writings, initially, without being arrested. Similar walls then sprung up under the noses of the authorities in other Chinese cities. For this apparent opening to democracy, the Deng regime much applauded, particularly by some in the Reagan-Bush Administration, eager to legitimize the regime and its growing commercial ties with U.S. corporations. Eventually, many of those who had availed themselves of the wall to post political messages were, of course, arrested in the roundup of hundreds of thousands of democracy supporters that followed the Tienamen Square massacre. The impression of anonymity and "freedom" conveyed by the Internet, of course, presents a similar opportunity for police to cast a wide net for identifying persons and organizations who may not hold favor for the regime in power, or may not in the future.

Hinckeldey also founded the Police Union, the first recorded international network of counterrevolutionary police spies in modern times. Primarily made up of police officers from Prussia and the German states, the Union operated throughout Europe, Britain and in the United States. The Union was run by his deputy, the notorious police provocateur, Wilhelm Steiber, who would later reorganize the Okhrana along similar lines. Internationally active from 1851-1866, the Police Union, according to Mathieu Deflem, was "one of the first formal initiatives in industrial society to establish an organized police system across national borders."13

In 1850, as chief of the criminal police in Berlin, Steiber personally travelled to London where he spied on Karl Marx and other radical Germans. Adopting the cover name Schmidt, Steiber set himself up as an editor of a communist publication, collecting information on radical circles which was used as evidence in the first international prosecution of communists in Cologne in 1852.

Steiber also oversaw a network of agents in the U.S., who infiltrated and gathered information about European radicals. Police Union agents surveilled booksellers and publishers handling German-language publications in the U.S.. In the late 1850s, a secret ban was placed on all German written materials emanating from America, judged by the secret police in Berlin as a fountainhead spreading "'democratic tendencies' which might lead 'to undermine monarchic foundations and Christianity and ethics'".14 The Police Union also shadowed figures in America associated with the German democratic movement. One of the major targets of this spying was Karl Schurz, a militant democrat, who after immigating to the U.S. in 1852 "became a confidant of President Lincoln, U.S. ambassador to Spain, a general of the Union armies during the Civil War"15 , Secretary of the Interior, and a leader in the Republican Party of the turn-of-the-century anti-Imperialist movement in the U.S.

The Police Union was really only one key component in the international police effort put together by the autocrats of central Europe to thwart the encroaching forces of modernism, nationalism, and middle-class self-government. With the Imperial secret services of Germany, Austria and Russia providing intelligence, in 1848 the Russian Army carried out the first coordinated international counter-insurgency campaign of the modern era. Nicholas' initial success in putting down the democratic movement was to be followed by a disasterous military defeat for Russia in the Crimean War (1853-56). Devastating losses to the Turks revealed the general backwardness of Russian arms and organization. Czar Nicholas I died of poisoning on February 18, 1855.

Spurred by his late father's humiliating defeat in the Crimean War, Alexander II (r. 1855-1881) set out to implement a series of important reforms, including modernization of the secret police along Prussian lines. Renovation of the Okhrana's international counter-revolutionary program seems to have been, in fact, the brainchild of Wilhelm Steiber.

After he was dismissed from his Berlin police post in 1858 for abuses of power, including his politicization of the criminal police and his particularly brutal interrogation techniques, Steiber was hired in St. Petersburg by Alexander II to overhaul the Okhrana. He there duplicated many of the functions of the Police Union, greatly expanded the Okhrana's use of informants and agents provocateurs to penetrate the growing ranks of Russian revolutionary groups.

Steiber, until ill-health forced his retirement in the mid-1870s,16 was at the center of a global nexus of counter-revolutionary police groups. Deflem reports, "(b)etween 1860-66, he combined his job of chief of the "Central Bureau of Press Matters" (a Prussian institution to collect information on international anarchists and communists) with espionage work for the Russian secret police."17

In 1863, Steiber returned to Germany and was appointed by the newly-installed Chancellor Otto von Bismarck as the first head of the Central Intelligence Bureau (CIB) and chief of military counterintelligence. By the time of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Steiber was the head of an army of some 20,000 paid spies working for Germany.

After the war, Steiber's Prussian secret police network, also known as the Sicherhiet Dienst ("Security Service"), kept close watch over and manipulated German society as the personal arm of Chancellor Bismarck and the crown. In the process, the CIB often bumped heads with other powerful factions within the regime, such as the German Chiefs of Staff, who in 1867 set up their own rival spy agency, the Abwehr ("Distant Surveillance Agency", or more generically, the "Foreign Information and Counterintelligence Department").

The Steiber organization, putatively concerned with protecting German ethics and Christianity by its censorship activities, in fact, ran bordellos and controlled newspapers. He used his extensive dossiers on domestic and foreign figures to blackmail many leading bureaucrats, publishers, industrialists and aristocrats in order to gain advantage over possible challengers to Bismarck's Imperium. After Steiber's retirement in the mid-1870s, his network was folded into the Abwehr, which was operated in a more legalistic fashion under the control of the General Staff.

Steiber can thus be counted as the father of the German Abwehr as well as of the Russian Okhrana, as he reorganized both into modern intelligence services controlling international rings of penetration agents and agent provocateurs. His dirty tricks operations also inspired several 20th Century heads of internal security who kept themselves, and their secret police agencies, in power through blackmail, intimidation and subversion from above. In the opinion of intelligence writer Jay Robert Nash, Steiber "created psychological warfare, censorship, and women as bait to gain intelligence, an espionage game that he taught everyone to play unfairly."18

Steiber may have learned as much about dirty tricks from the Okhrana as they did from him during his years in Russia. The international exchange of secret agents and intelligence on radicals continued into the next century. Okhrana master spy Arkadiy Harting, (aka Abraham Gelel'man, Hackelman, Hartmann, Landsen or Landezen) was a master of the art of disguise, political provocation and destabilization.

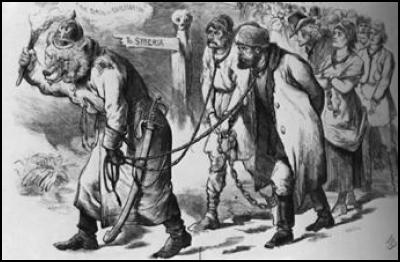

The Father of False-flag Terrorism

From 1890-1909, Harting was the paymaster, and chief strategist of the most violent faction within the Russian émigré movement in France. Shortly after his arrival in France from an Okhrana posting in Berlin, he killed a French policeman. Using the pseudonyms "Hartmann" and "Landsen", he established his revolutionary bonafides by killing a French policeman. The French government's seemingly inexplicable refusal to deport him back to Russia was a source of considerable outrage among French and Russian public opinion. (D.W. Brogan, France Under the Republic (1870-1939). New York: Harper & Bros., p. 312). During his illustrious career, Harting had been decorated by the governments of czarist Russia, Imperial Prussian, and the French Republic for his struggle to suppress international terrorism.19 Legend has it that he disappeared into Brussels, not to be seen again.

While Germany assumed many of the trappings of a constitutional monarchy after its unification in 1871, Russia remained an autocratic state until 1905. The Czar's secret police thus remained free of the sort of incremental legalistic constraints that bound German intelligence. Thus, by 1890, the Okhrana had emerged as the most powerful and ruthless secret police organization in the world. Even in the face of mounting nationalism and (largely futile) attempts at bureaucratic control, the Okhrana continued to operate in Russia and abroad as virtually a sovereign agency, acting according to its legacy as a Praetorian Guard of powerful factions within the still very much Germanic aristocracy of Russia.

Okhrana's self-described mission of protecting autocracy put it above the laws of any nation in which it operated. For good reason, it was greatly feared by exiled Russian and Polish radicals, but these Leftist refugees were largely outside the protection of the law. With the exception of Great Britain, France, and to a lesser extent the U.S., Russian and Polish exiles were treated as enemy aliens with no rights in the countries where they sought refuge.

Because Russian international espionage against other states differed little from the secret services of many neighboring countries at the time, the Okhrana attracted no special international notoriety until after the turn of the century. Most governments watched their own political dissidents abroad, usually through the more casual surveillance of Embassy staff. While the autocratic regime of Imperial Russia was not greatly popular among the western publics, its political exiles were widely seen by western officials as a menace.

Until they were recruited after the 1917 Revolution, the Okhrana were treated in a largely fraternal fashion by the intelligence and police apparatus of most western states, which viewed the Czar's secret agents as valuable sources of information about anarchists and communists. The Okhrana's terrorist activities against the exile community were usually overlooked, covered up, or blamed on the victims.

Footnotes:

1......... The Okhrana is reported to have compiled "over 40,000 reports from 450 agents and informers operating in 12 countries", according to a summary of the contents of the archives of the Okhrana's Paris bureau, now housed at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University. See, Description of Contents, Russian/Commonwealth of Independent States Collection, p. 3, ;.2......... While primarily an internal security agency, Okhrana's biggest foreign espionage coup was its compromise and recruitment of the head of the Austrian counter-intelligence corps, Colonel Alfred Redl, who provided voluminous information to the Imperial Russian Army during World War One. In return, Okhrana plied Redl, who committed suicide when discovered in 1914, with huge amounts of cash and with numerous homosexual partners. See Jay R. Nash, Spies: A Narrative Encyclopedia of Dirty Deeds and Double Dealing from Biblical Times to Today (New York: M. Evans & Co., 1997) at pp. 387.

3......... The Okhrana has a curiously intertwined relationship with the Knights of Malta, originally a Catholic military order dating back to 1099, as well as the nobility of Europe. The Knights of Malta fragmented into a number of national and religious factions after 1798, when Napolean evicted the Order from its fortress stronghold on the island of Malta. Paul I, the Emperor of Russia, was the sole European ruler willing to give asylum to the knights, who had a deserved reputation for intrigue on behalf of the Roman Pope. The Czar then took over the Order, appointing a large number of newly-admitted Eastern Orthodox knights -- many of them members of the Czar's Imperial Guard -- who founded a new Priory in Russia. The Czar was made Grand Master of the whole Order, an election that was bitterly contested. Paul I was assassinated soon thereafter, which suggests the possibility, at least, that the takeover ploy may have worked both ways.

After the British refused to return Malta to the Order, the group fissioned into sects serving various crowns and nations. The Orthodox Knights Hospitaller (the Sovereign Order of Orthodox Knights Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem) continued to serve the Czar until the Bolshevik Revolution. The survivors of the Order moved to the United States, where today it is headed by Grand Bailiff Count Nicholas Bobrinskoy, descendent of Catherine the Great of the House of Romanov. The Order is closely associated with the Russian Orthodox Church, and currently operates in both Russia and the U.S.. The chaplain of the Order, Fr. Christopher Calin, is rector of the Holy Protection Cathedral in New York City.

The Orthodox Knights claim no allegience to various western Orders. See, the website of the Orthodox Knights of St. John: ;; Cf., the websites of the Rome-based Sovereign Military Order of Malta, Federal Association, USA ;; see also, The Order of Malta in Great Britain, which describes itself as "the world's oldest extant order of chivalry". ;. This site offers the most extensive history of the three, and describes the Order in England as having been "established in the first half of the twelth century and, like the rest of the Order, received a great accession of wealth and property when the Templars were suppressed in 1312." The English, along with the German and Austrian Orders require proof of hundreds of years of nobility for candidacy into the highest grade, in the UK "most of our knights of old Recusant families."

4......... Ward Thomas, "Norms and Security: The Case of International Assassination", INTERNATIONAL SECURITY, Vol. 25, No. 1, 105-33 (Summer, 2000).

5......... Thomas, Ibid., at 110.

6......... See, Russia: A Country Study. (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Federal Research Division, 1996), "The Evolution of the Russian Aristocracy",; Cf., Empress Catherine II "the Great", The Alexander Palace Time Machine Bios, ;.

7......... The Alexander Palace, Ibid.

8......... Ibid.

9......... Russia, A County Study, Ibid., "Reaction under Nicholas I".

10...... Quoted by Alan Knight in Alan Palmer, ed. Age of Optimism, (New York: Newsweek Books, 1970) p. 116.

11......... Ibid.

12......... See, R.R. Palmer, A History of the Modern World, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1951), p. 492.

13......... Mathieu Deflem, "International Policing in 19th Century Europe: A Case Study of the Police Union, 1851-1866." ; p. 1, manuscript version of "International Policing in 19th Century Europe: The Police Union of German States, 1851-1866." in International Criminal Justice Review 6:36-57 (1996).

14......... DeFlem, Ibid., pp. 5-6.

15......... Ibid., p. 6.

16......... Jeffrey T. Richelson, "A Century of Spies", Chapter 1, p. 3 ;. That account relates that the Abwehr, "foreign information and counterintelligence department" was originally established in 1867 by Prussian General Chief of Staff, Helmuth von Moltke, as a competitor intelligence agency to Steiber's CID, which answered directly to the Prussian Kings and then to Bismarck. Steiber's death in 1882 "permitted the generals to seize control of military intelligence". Ibid. The German General Staff would maintain this power until 1918, when the Abwehr was temporarily disbanded until its reconstitution under the Versailles Treaty in 1921. Steiber was thus the indirect father of both the Okhrana, after reorganization into the Third Section, and of the German Abwehr.

17......... Deflem, Ibid., p. 9. DeFlem fails, however, to point out the key supporting role played by Alexander II in the counter-insurgency campaign of the Prussian and Austrian royals against middle-class nationalism in central and eastern Europe. The international Police Union, which DeFlem's essay describes, was a critical part. The apparent exclusion of the Okhrana from the Police Union in DeFlem's account is curious, except as Steiber can be inferred as forming a personal and professional link between the two implicitly separate counter-insurgencies.

2006. Mark G. Levey. See Mark's Daily Kos Diary

ENDS

Binoy Kampmark: Rogue States And Thought Crimes - Israel Strikes Iran

Binoy Kampmark: Rogue States And Thought Crimes - Israel Strikes Iran Eugene Doyle: The West’s War On Iran

Eugene Doyle: The West’s War On Iran Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia

Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal

Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest

Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest