NOLA Lost: 72 hours in America’s other Ground Zero

NOLA Lost

72 hours in America’s other

Ground Zero…

By Charles Shaw

Click for big version

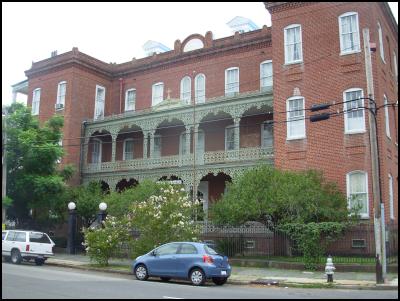

The St. Vincent’s guesthouse is a living metaphor for the city of New Orleans. The big, beautiful, bricked, French colonial structure on Magazine Street in what’s known as the Lower Garden District is a majestic presence. Wrapped in vines with an iron portico over the entrance forged in the traditional floral pattern that is characteristic of the Quarter, you are wowed and enticed by her beauty when you take her in for the first time. But step inside and the veneer suddenly drops and you find yourself unwittingly submitted to the hustle. For the interior of St. Vincent’s belies the soul of New Orleans: poor, black and desperate.

But the desperation in New Orleans no longer discriminates. It washed through the city astride the storm surge of a year ago, and remained when the waters receded, a dark ring constricting the city like the ubiquitous waterline that has become the unofficial monument to Katrina.

Click for big version

You can feel it right away when you land at Louis Armstrong airport and realize you’re the only flight in sight, and the gates stand empty, their gangways retracted and tucked into the terminal wall. You smell it when you walk through an empty terminal to baggage claim only to find your bag waiting for you, and a line of taxi drivers eyeing you eagerly.

The thing is, there is no one in New Orleans. Most people moved away, and the tourists, on which the economy depends, haven’t come back either. You can hear a hint of it when the lady selling tickets for the airport shuttle says, “How long you stayin’, baby?” a bit too plaintively. In New Orleans, everybody is “baby,” but something in the way she says it now makes it intimate.

The shuttle whisks you Downtown on Airline Highway Rd. past fields of abandoned housing projects in the distance that look a hundred years old, and an old bleach white marble cemetery, each stone bisected by the ubiquitous horizontal brown line.

Downtown, the streets of the Quarter are empty, What is normally a vibrant and festive street scene of red-lit bars blaring Dixieland jazz and gift shops packed with beads, stuffed alligators, and Café du Monde now seems cartoonish and in bad form, a hustle as cheap as trying to sell the Brooklyn Bridge. Every third or fourth business is closed or for sale, and “50% off!” signs hang in the windows of the mostly empty shops that are still hanging on. Inside the music is too loud, and the shopkeeps stare out the narrow French doors across the rain swept cobblestones.

It makes you wonder how they can continue to sell kitsch when they know in their hearts that the whole world has seen the real New Orleans now, and the Mardi Gras shtick isn’t cuttin’ it any more. They’re going broke trying to sell a memory.

So too is the St. Vincent’s Guest House. It began in 1861 as an orphanage for the surviving children of the frequent malaria epidemics typical of the sub-tropical climes of southern Louisiana, and now uses the memory of all those poor children to market itself as a unique “historical” experience. Unless you are particularly enamored with architecture, the “historical” significance ends with a row of four old black & white photographs mounted on the wall depicting nuns in large habits administering to a roomful of tots. Because the place is so big, and noble, and has a small pool and a gorgeous Southern style courtyard, it could have made a top-flite hotel or bed and breakfast. Instead, it became a flophouse.

This, of course, you don’t know if you’re from out of town and your girlfriend happens across their website and thinks she’s booking you a room in a hostel with a “gourmet southern breakfast” and “free wireless internet,” because the website neglects to tell you that both are found across the street at a coffee shop called Mojo.

“You’re not staying there,” the short girl with the blond bob behind the counter says as she’s steeping my cup of dragonwell, which I am buying so that I can use the Mojo internet guilt-free. I’ve just checked in and discovered the place is awful, and now find myself lamenting to the bobby barista my concerns about being able to work on my story. “I’m sorry, that place is a shithole,” she continues. “You’re a brave man.”

Click for big version

“I believe the word you are looking for is poor,” I replied. A necklace round her neck reads “Sarah.”

“I caught someone from St. Vincent’s smoking crack in our bathroom,” she says. “It’s a pretty scary over there. Be careful.”

Mojo is populated by young bohemian aspirant whites who are part of a gentrification vanguard that has crept into this historically sketchy neighborhood on the banks of the river. This section of the Lower Garden District is more than 18 blocks from the Quarter, and I’m on the Internet trying to find my way to the offices of ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now) so that I can hook up with a couple community organizers and get a personal tour of the Lower 9th.

“Normally,” Sarah shouts over the hiss of the steamer, “I’d tell you to take the Magazine St. bus. But it doesn’t really run that much anymore. None of the buses or street cars do, not since.”

I decide to cab it. In the cab, the driver tells me I’m his first fare of the day. When I ask him how business is, he says his family is starving, his wife lost her job because of Katrina, and that there’s barely enough business to offset his gas costs. At an intersection another cab pulls up alongside, and the two men exchange a few words in their native language. Then the other drives off.

“He’s going home,” the driver laughs. “He says I’m hogging all the business.”

THOSE WHO STAYED

Click for big version

There are a lot of rolled eyes in New Orleans these days over the word ACORN. Equally, though, there is heartfelt praise, because they are a unique presence in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ever since the hurricane blew the roof off their offices on Elysian Fields road, the New Orleans chapter of the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now have stood side by side with the residents of New Orleans poorest neighborhoods, including the Lower 9th, and helped them recover by gutting their houses, helping them file their taxes and relief paperwork, train for jobs, find public aid, and fight the ceaseless onslaught by the big money interests who would rather they just not stay. They have even authored a set of planning principles called “Rebuilding After Hurricane Katrina.”

They are also the only thing that stands between the former residents of the Lower 9th and the 2005 Supreme Court decision in Kelo v. New London which extended Eminent Domain to commercial development. In simpler terms, the dirty little secret about New Orleans is that Ray Nagin and the powers that be in the Big Easy are involved in a land grab of historical proportions.

Click for big version

It’s actually not that big a secret in New Orleans. ACORN’s red and white “No Land Grab” and “No Bulldozing” signs are on virtually every house in the Lower Ninth, and their public campaign to save property rights is the leading cause of the aforementioned eye-rolling. Most of the signs went up in protest to an ordinance passed on August 29th that authorized the city to take any house or plot of land not already under redevelopment. This meant all homes and lots had to be cleared of all debris, and structures boarded, plans made, and permits filed. Forgetting that most of the residents were poor and completely wiped out, those who did try will tell you they faced every obstacle imaginable.

“We had to fight just for the right to come back,” ACORN’s Marie Hurt says as we circle block after block in the 9th. “One of our Directors had to go to Washington to testify that the National Guard had closed off the Lower 9th and homeowners were not being let back in. The Lower 9th wasn’t the only neighborhood that flooded, but it was the only one closed off by armed troops.”

Hurt’s pissed. Everyone is gone, she says. There is no one left to fight for what is right, and the powers that be know this.

“Two weeks ago when everybody was talking about Katrina [at the one-year anniversary], where did all the media go to interview people? Not here. They went to Houston to interview people about New Orleans.”

Click for big version

In the passenger seat is Gwendolyn Adams, an ACORN volunteer. We’re headed to the former site of her home that sits in sight of the spot where the levee broke. The levee wall was replaced by a mile long concrete monolith that eerily resembles the apartheid wall in Israel. It may convey a renewed sense of strength and security, but it is, of course, far too little too late.

Click for big version

House after house bears the same familiar spray-painted system of code the National Guard rescuers used to mark when the house had been checked, whether the house was entered, if there were bodies, and so on. So many houses have “DOG TRAPPED” on them that I stop looking. Hurt tells me they are still finding human remains inside homes, and Adams says the official body count is much higher than what has been reported.

She notices I am still upset about the dogs and tells me that her dog was saved, that she left him on the porch and one day six months later an animal rescue volunteer called and said they found him and called the number on the tags.

“it was one of the most beautiful surprises of my life,” she says. We cross Tulpelo St. and drive past the former site of the Jackson Army Barracks. Adams points out the gates surrounding it.

“That’s going to be a $300 million residential project with a bank and supermarket. Part of the new Mid City plan. They are trying to discourage the [original] residents from returning any way they can. That’s why they won’t open the school. It’s a pretty calculated plan on the part of the city.”

North of Claiborne, somewhere around Derbigny St. we enter the zone that still has no working electricity or potable water. Most of the area is open space where once homes and cars sat. Grass and weeds grow six feet high. Former homes dislodged from their foundations sit in ramshackle piles after having floated across the street.

Click for big version

Cars are arrayed atop one another like a hand of playing cards.

Click for big version

Stuck in the ground before an empty plot is a large photograph of a middle-aged man bearing the words “rest in peace”, an impromptu memorial to one of the many victims. Looking around you see that nothing has been spared. Nothing.

Click for big version

The car stops in front of a house that is laying astride an upside down pickup truck. Next-door is an empty plot of land where Gwendolyn Adams’ home once stood. She gets out of the car and stands in what was her driveway.

“They just took my house. Without asking me. I came here one day, and everything was gone. Even the house that had floated on to my property and settled on top of mine was gone,” she laughs. “I don’t mind the help, but they didn’t ask my permission or even tell me. Multiply that by the whole ward, and you got what’s going on down here. Property rights have been thrown right out the window.”

As we leave the Lower 9th, just before we cross over the canal to go back Downtown, we pause at the corner of Jourdan & Claiborne. In the median strip of Claiborne is an ugly abstract sculpture made to resemble room with chairs and a window. Taped in the window is a sign that reads “I Am Coming Home! I Will Rebuild! I Am New Orleans!”

Click for big version

“Our City Councilman put that up,” Hurt says. Then, adopting a melodramatic tone, “to remember all the people that died.” Her and Adams laugh. When I inquire as to why they are laughing, Hurt continues, “cause it’s total crap. He doesn’t care about us. And he sure don’t want us to come back!”

Adams picks it up. “The people who he wants to come back ain’t never lived here!”

They laugh, they say, to keep going, because there’s nothing else they can do. They cried all they could cry about it.

“The only people still cryin’ about New Orleans are the ones who left,” Hurt says. “Those of us who stayed don’t have time for it.”

We cross the bridge back to the Quarter, and higher ground.

Click for big version

Dawn Marie Hurt moved from Florida to New Orleans after college because “it wasn’t Florida.” She has been an organizer with ACORN for nine years. But more than that, she’s a real member of the community. She lives amongst the people she serves, has a bond with them that makes everything she does track back to her community, her people. Her home was destroyed under four feet of water, but she never left the city. And she tells a very different story about the aftermath of Katrina than most are familiar with.

Click for big version

“Everyone is always talking about the looting and the crime and how great Ray Nagin was. The reality is totally different. The police did most of the looting I saw or heard about. They raided the Gene’s [famous daiquiri shop] next door to our offices. And nobody likes Ray Nagin cause he’s all about the money. He’s an embarrassment.”

We’re sidled up to the bar at the Spotted Cat on Frenchman St. It’s a quiet Saturday afternoon, and sporadic rain pelts the narrow street. It’s only us two, the bartender—a friendly woman roughly our age—and an older black woman hunched over a video poker game who claims her “brother” owns the place. She’s on a roll, winning hand after hand, stepping back to the bar to claim her winnings and pick up another Bud Light. Marie tells the bartender I am writing an article about what’s really going on in New Orleans.

“Well, you’re in the wrong place, then, cause there ain’t shit goin’ on in here.”

We laugh, and she asks me where I am staying. I tell her the St. Vincent’s guest house, and she laughs again, this time much harder.

“Your magazine should be brought up on charges for not getting you a decent hotel room. I lived there for six months when I first moved to New Orleans. It’s great if all you need is a bed. But I wouldn’t ever leave anything in the room, and I’d keep your lock dead bolted when you sleep.”

I think about the fact that my laptop, half my money, and other necessary personal items are still in my room. A low-grade panic begins to rise.

Hurt goes on to tell me that New Orleans is “just a huge experiment, with Washington directing everything.” She cites as an example how the State of Louisiana took over the New Orleans public school system and 7500 people were put out of work. Now, the State is replacing it, with help from the Federal Government to the tune of $500 million, with a privatized charter school system, and hiring all new teachers from outside the region at greatly reduced salaries and without the same quality of benefits. The bank is closed for the public system. What may Be more telling about this plan is that there is a significant amount of real estate that was owned by the Board of Education that has now been appropriated by the State government.

It keeps coming up again and again. Land Grab.

Click for big version

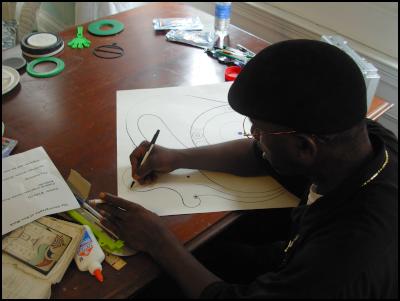

It was back at St. Vincent’s later that evening that I met Welmon Sharlhorne. Welmon spent 27 years in a Louisiana state penitentiary, where he learned to create art out of whatever he was able to scrounge. Cups and tongue depressors from the nurse for making curves, manila envelops mailed from his lawyer, taped together to make canvases, and stolen pens and pencils. He created less than fifteen paintings while incarcerated, but they were enough to garner him international acclaim, a show in Switzerland, and a listing in Contemporary America Folk Art, an early ‘90s compilation put together by Folk Art collectors and scholars Chuck and Jan Rosenak.

Welmon is seated at a table working on a new drawing, cigarette smoke permeating the hot and humid day room, a tragically old and worn copy of the Rosenak book sitting amongst his pens and compasses. Delta blues blare from a portable CD player. Welmon tells me he’s “dangerous.”

“People pay me $150 if they want to interview me,” he says, tapping the Rosenak book. “Whatchou gonna write about me?”

I tell him I don’t know at the moment, I was just curious about what he was doing.

He shakes his head. “Man…gimme twenty dollars.”

Welmon lived in the Lower 9th, but his house was destroyed, so he came to live at St. Vincent’s. He’s part of a larger diaspora of displaced blacks and ex-convicts that populate the guesthouse. There’s no real staff except for three women who generally man the front desk in three shifts, to collect the keys and money. There are no amenities, not even towels. Most of the residents seem engaged in some sort of labor involved in the perpetual rehab of the premises. At night, they all gather in the courtyard to drink Crown Royal and smoke cheap weed.

Click for big version

Sometimes a few of the younger men jump in the pool. Paying close attention to the social dynamics for a few moments reveals that each of the three desk women is romantically linked to at least one of the male residents, and that tensions have recently erupted on the night shift over territoriality. Every night Welmon passes out in the same chair on the courtyard, mouth agape, and sleeps until sometime in the wee-hours of the morning, when he finally shuffles up to bed.

I’m back in the Quarter at the Spotted Cat on Sunday to experience the “Dixieland Brunch” which the bartender had raved about the day before. Outside is a tropical deluge, the rain pouring in sheets off the porticos like everyone’s cinematically ideal New Orleans. On the tiny stage at the front window is a six piece—guitar, banjo, drums, piano, trumpet, upright bass—with a guest vocalist, a robust brunette who calls everybody a breathy “baby.” The brunch consists of fried pork chops, corn, and rice with beef, and it’s served on the bar in a couple crock-pots and an aluminum dish. It’s, for me, a vegetarian’s worst nightmare. It’s also typical of New Orleans.

Grub aside, the vibe in the room is extraordinary. The band is hopping, and the rain in the background adds depth and texture to the music, and when the lady sings the blues the windows vibrate from the low-gut force of her voice. A young couple decked out in swing gear jumps up and begins Lindy-hopping across the tiny space available for a dance floor. Flip, spin, hop. The buxom lady sings…

…another season

another reason

for makin' whoopee..

It’s a Sunday in New Orleans, and it’s time for shtick, cause its time to pay the bills. But there on the barstool, five feet away from a woman in a dress in a dark and damp club with no PA, a concrete floor, and food you wouldn’t feed a P.O.W., drunk and loud and happy, you finally know you’re in New Orleans. And when you pull back and listen to the street, you hear the sounds of a hundred other Dixieland bands, playing in their own bars, sometimes to two and sometimes to twenty, but playing on, making their bread, doin’ their thing, and hoping it goes on.

You can’t stop playin’ just cause it’s rainin’ the lady sings as I move out of range.

Later that night, I head deep into the Quarter to Déjà vu on Dauphine St. to wait for some old friends I keep trying to reach. The problem with post-Katrina New Orleans is that it’s hard to connect with people because so many just up and left either willingly or out of necessity. I left messages telling these friends I would be at Déjà Vu after 6:30, and to come and meet me. I picked the place on the recommendation of a mutual friend who had been down to visit the same people pre-Katrina and raved about the place. My first impression of the place as I walked in was a drunk being ejected. My lasting impression was that of a urine-soaked tourist trap. But apparently, they had a reputation for great steaks. Again with the meat.

Behind the bar are two young girls named Eliza and Christina who together were about my age. Eliza has full sleeves of tattoos and a Russian sailor’s cap and striped t-shirt. Christina is all in black with a cameo choker around her neck. She chain-smokes slender vanilla cigarettes in the corner of the bar and grieves to the middle–aged bouncer leaning in close to listen. She has just thrown her boyfriend out, she says. She is tired, and had taken a lot of ephedrine to get through her shift. She doesn’t know what she wants to do.

When she passes by me next, I reach out to grab her attention, order a bloody mary, and tell her I couldn’t help but overhear, and that it would get better, she just needs to hang on. When she finally stops moving and focuses her eyes on me, the depth of sadness they carry is a bit too unsettling for me, and I thought to myself that someone so young shouldn’t feel such sadness, and chided myself for being so trite.

But when you looked around, you started to realize that the luxuries of a bourgeois society weren’t necessarily available to everyone in New Orleans anymore. That for most, survival had superceded choice. Both girls worked two jobs in the New Orleans service economy, neither providing enough income to live on, despite occupying most of their time.

I overhear the guy sitting next to me mention the word “Chicago,” and discovered he lives in Antioch, where my grandparents once lived. His name, naturally, is Joe, and he is a mason. He tells me there is more work than anyone can believe in New Orleans if you are in the building industry. So much so he’s able to split his time between Chicago and New Orleans. I ask him why, if there is so much work, that no one in New Orleans can find a job. He explains that all the labor is being done by Mexican migrants for a fraction of the cost, and that “half of them ain’t getting’ paid anyway,” which he claims is intentional because “there ain’t much they can do about it, right?”

After more than two hours of waiting, I figure my friends aren’t coming, and I leave. The rain has abated and the streets are slick and shiny and the street has a little life to it. I walk a bit down Dauphine, and run into a street musician leaning against the wall smoking a cigarette, a saxophone hanging around his neck. I ask him to point me in the direction of Magazine St. As he begins to explain, a white kid with a buzz cut rides by on a bike peddling meth.

“Ice. Got ice. You know you want it.”

The kids rides on, the jazz man starts to play again, and I head east towards St. Vincent’s, a walk which will take me some 40 minutes to complete. I go past the Holiday Inn where the National Guard has lived for over a year, on taxpayer expense, and see row after row of Humvees choking the parking lot. Just as I arrive at St. Vincent’s the skies open again and the rain comes hard. In the courtyard, passed out in his chair, I find Welmon, an empty bottle of Crown Royal in his lap.

Click for big version

When I get to my room, I find my door is unlocked, and a little investigation reveals someone has been in my room, and absconded with $150 in cash I (like an idiot) had stashed under my mattress in the event of an emergency, or mugging. My laptop is safe in another location, leading me to believe the person found the money first, and took it and ran. There is, of course, no one to report this to, so I deadbolt the door and fall into bed, the rattle and hum and of the window unit keeping time with the rhythmic drip drip dripping of condensed water on the ceiling to the carpet below.

Monday was the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, but no one in New Orleans seemed to be paying attention. And why should they. While the rest of the nation was glued to a tiny plot of land in Lower Manhattan they call “ground zero,” an entire city lay in ruins like the real Nagasaki, and hundreds of thousands are still homeless. And while the populace is bludgeoned to death about the “evil” that we face from those abroad, there is no talk of the those that were left to die here, or the “evil” that exists when a government is so over-mortgaged in people and expenses that they can’t even take care of the mess in their own backyard.

This we do know: 9/11 and Katrina share one thing in common, they reveal what our government considers worthy of value and attention, and what it does not. 16 acres in Lower Manhattan and 3,000 largely white New Yorkers have equivocated to a hundred thousand dead Muslims. But the people of New Orleans thus far have been considered expendable, a hindrance to “development.” Immediately after 9/11 there were calls far and wide to rebuild, and five years later there is nothing but a gaping hole in the ground and a lot of blustery rhetoric. A year and some $110 billion in “reconstruction efforts” later, it still remains to be seen what will become of New Orleans. But one thing is for certain, it will never be what it once was, because those calling the shots don’t want it to be. They want a Disneyland version of New Orleans, one that completely ignores the contributions of the indigenous, which largely made New Orleans what it was.

But then again, this shouldn’t be a surprise. Despite becoming synonymous with the place, Louis Armstrong refused to be buried in New Orleans because of its long history of segregation and racism. He once famously said, "The way they're treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell" and that he could not represent his government abroad when it was in conflict with its own people at home. Little has changed today. Even Louis Armstrong couldn’t go home again, and no measure of monument erected in his honor could ever change his mind.

Click for big version

Change will come, to every corner of New Orleans, whether it is ready or not. All around St. Vincent’s is the telltale Tyvek house wrapping characteristic of new development, and change is coming to St. Vincent’s as well. While I was paying for a last dragonwell on my way to the airport, Sarah at Mojo tells me that she found out that morning that St. Vincent’s had been bought and will be turned into a halfway house for recovering drug addicts.

Click for big version

“Ironic, doncha think?” she says.

I pause.

“Appropriate,” I say, and wave goodbye.

Charles Shaw is the Editor in Chief of

Conscious Choice Magazine, and a regular Contributor to

Scoop.

Gordon Campbell: On NZ’s Silence Over Gaza, And Creeping Health Privatisation

Gordon Campbell: On NZ’s Silence Over Gaza, And Creeping Health Privatisation Richard S. Ehrlich: Pakistan & China Down 6 Indian Warplanes

Richard S. Ehrlich: Pakistan & China Down 6 Indian Warplanes Keith Rankin: War In Sudan

Keith Rankin: War In Sudan Ramzy Baroud: Netanyahu's Endgame - Isolation And The Shattered Illusion Of Power

Ramzy Baroud: Netanyahu's Endgame - Isolation And The Shattered Illusion Of Power Jeremy Rose: Starvation Of Gaza A Continuation Of A Decades-old Plan

Jeremy Rose: Starvation Of Gaza A Continuation Of A Decades-old Plan Keith Rankin: The Aratere And The New Zealand Main Trunk Line

Keith Rankin: The Aratere And The New Zealand Main Trunk Line