Scoop Review: Eyes Of Fire, A Reminder Of When Nuclear Wars Came To Town.

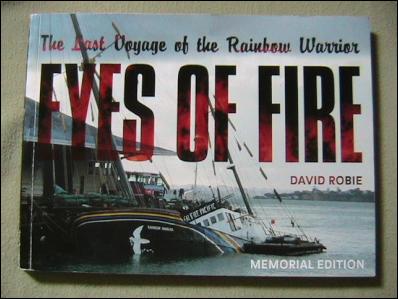

The memorial edition of David Robie’s Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior (Asia Pacific Network : Auckland, 2005) is an in depth look at the last voyage of the Rainbow Warrior. Originally published in 1986, it brings the era to life in a way that a more retrospective book could not do. Robie himself lived that last journey through the Pacific on board the Warrior, and New Zealanders are the luckier for this fact. He allows us all to share in the historic adventure, which was, of course, cut tragically short by the French bombing of the now famous ship.

More than pure nostalgia, however, Eyes of Fire also provides a detailed and analytical snapshot of the strategic environment in the South Pacific in the early to mid-1980s.

Twenty years before the present conflict between the Japanese whalers and Greenpeace activists, the ecological movement had pronounced 1985 as the Year of the Pacific. The era was one that unified Pacific peoples in solidarity. Despite the relative meekness of our various governments, Greenpeace’s campaign helped empower our region to resist becoming the nuclear cesspit of the world’s great powers.

The period really was a coming of age for Pacific nations. Prime Minister David Lange’s outspokenness on the nuclear issue remains a source of pride for New Zealanders. Robie highlights the idealism of other, lesser-known Pacific leaders, whose support for a nuclear-free Pacific was no less principled and vigorous.

Prime Minister Walter Lini of Vanuatu, in particular, linked the pollution of the Pacific closely with colonialism:

The people of the Pacific have been victimized too long by foreign powers. The Western imperialistic and colonial powers invaded our defenceless region; they took over our lands and subjugated our people to their whims. This form of alien, colonial, political and military domination unfortunately persists as an evil cancer in some of our native territories such as Tahiti, New Caledonia, Aotearoa [New Zealand] and Australia.

Our environment continues to be despoiled by foreign powers developing nuclear weapons for a strategy of warfare that has no winners, no liberators and imperils the survival of all humankind…

Likewise, in the Marshall Islands, Senator John Anjain collaborated with Greenpeace to evacuate the entire population of his homeland, the picturesque Rongelap Atoll. The Atoll was the site of a thermonuclear explosion by the U.S. in 1954 – in the years that followed, the Rongelapese islanders were and are plagued by radiation-linked illnesses and deaths, stillbirths, deformities and miscarriages. Studied by American scientists as guinea pigs for 30 years, their island had been turned into a laboratory. The moving story of how the islanders finally escaped the death sentence of their people on the Rainbow Warrior is appropriately given a whole chapter in Eyes of Fire.

No less heartening is Robie’s accounts of the broad-base, grass-roots support Greenpeace received across the Pacific. From the welcoming of the Warrior crew by the Kiribati Islanders and their attendance at numerous public meetings, to their warm reception in Port Villa, Vanuatu, the nuclear-free mission was warmly embraced.

The anti-nuclear movement, which pre-dated Greenpeace, was solidified as the historic Rarotonga Treaty in 1985 by the South Pacific Forum.

The impact the South Pacific had upon Greenpeace is also interesting. Compared to previous campaigns in other parts of the world, Greenpeace had to be careful to work with the islanders and avoid being overly confrontational. Robie has an insider’s perspective on the planning that went into achieving this. The activists also found it difficult to maintain their distance from partisan politics in an environment where nuclear testing was so intertwined with independence movements and anti-colonialist sentiment.

Above all, the Rongelap evacuation and actions taken at the U.S. Kwajalein Missile Range opened ‘a whole new chapter in Greenpeace: the importance of humanitarian missions as an integral part of the environment campaigns.’

Given the context of the time, as detailed by Robie, the revelation that France was amongst the countries that New Zealand spied upon in the recent exposé of the top-secret Government Communications Security Bureau report by the Sunday Star Times is no shock.

France was, especially in the 1980s, a serious threat to New Zealand’s national interests and South Pacific security in general. It was the world’s third-ranked nuclear power – a global superpower – vastly more militarily capable than any Pacific nation.

Having recently lost most of its North African colonies, France was determined to hold onto to its Pacific territories. France’s strategic interests in the region include New Caledonian nickel mines along with other ores integral to arms manufacture. President Mitterrand planned a strategic military base in New Caledonia – to be the biggest in the South Pacific.

Furthermore, under Mitterrand, France followed a strategy of close cooperation with Washington. While both were technically New Zealand’s allies, these were two of the world’s strongest nations who had serious issues with our policy on nuclear testing and weaponry.

Although the Cold War was raging, Robie argues forcefully that the real threat to South Pacific stability was not the risk of Soviet infiltration but rather French and U.S. colonialism. Quoting a report by Pacific affairs specialists Dr Robert Kiste and Dr Richard Herr, Robie shows that the ANZUS nations tended to exaggerate the dangers of the very minimal contact the Soviets had with any Pacific nation.

The bombing of the Warrior alerted New Zealand authorities to something very sinister: not only was the intelligence division of the DGSE active in New Zealand, but the ‘most important and most notorious of the three branches’, the Action Service, was as well.

While on the surface, France was an ally to New Zealand, the nation was prepared to infringe upon New Zealand’s sovereignty to protect its colonial interests. French statements to the effect that opponents of French nuclear tests were to be ignored and seen as ‘adversaries’, should, according to Lange, ‘be properly be translated as enemies.’ The terrorist attack on the Warrior in New Zealand waters was an ‘affront to sovereignty’. Thus it is not at all surprising that New Zealand was spying on the French.

The power of information, was, after all, essentially what motivated the French attack on the Warrior. A letter by the mayor of radio-actively contaminated Mangareva Atoll, Lucas Paeamara says it all:

‘The sad truth is that the only ones who have tried to help us are the Greenpeace ecologists. But was this fear of having scientists poking their noses into the Mangareva mess really a sufficient reason for the French secret service to embark on the risky operation of sending combat divers to Auckland harbour to sink the Rainbow Warrior? For we must not forget that the 3,000 French soldiers and foreign legionnaires on Moruroa could easily have repulsed an attack by a dozen ecologists. We must look for a more convincing motive, which, alas, isn’t difficult to find. Greenpeace had planned to include on the Warrior doctors and scientists ready to undertake the health survey the Territorial Assembly has been clamouring for since 1981 – and to start it at Mangareva! The ultimate aim of the sabotage was thus to prevent the unpleasant truth from becoming known.’

In June 2005, a month prior to marking 20 years since France bombed the Rainbow Warrior while berthed at Marden Wharf, Auckland - killing Portuguese-born photographer Fernando Pereira - David Robie said: "Two decades on we should keep a sense of perspective – this was an outrageous act of war against a friendly sovereign nation and an act of terror against a non-violent global protest organisation.”

As is so often chanted in remembrance of other acts of war: Lest We Forget.

Scoop highly recommends this book.

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal

Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest

Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels

Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels Keith Rankin: Remembering New Zealand's Missing Tragedy

Keith Rankin: Remembering New Zealand's Missing Tragedy Gordon Campbell: On Why The Regulatory Standards Bill Should Be Dumped

Gordon Campbell: On Why The Regulatory Standards Bill Should Be Dumped