Buthina Canaan Khoury at Palestine Film Festival

Buthina Canaan Khoury at Chicago Palestine Film Festival

By Sonia Nettnin

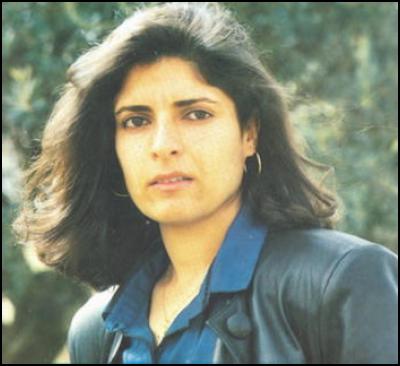

Director Buthina Canaan

Khoury (Photo courtesy of

WomeninStruggle.com)

She established good relations with all four Palestinian women. As a result, Director Buthina Canaan Khoury completed her first documentary, “Women In Struggle,” in four years. After 39 hours of footage, she edited her film to 56 minutes with seasoned decisions. Her documentary is about women who are ex-political detainees, and it is from the Palestinian point of view.

When Khoury was at the Gene Siskel Film Center for the 2005 Chicago Palestine Film Festival, she spoke with natural spontaneity. Her knowledge showed an expertise in not only her film’s subject matter, but of Palestinian cinema, culture, history, and politics.

Moreover, she emanated grace.

“I’d like to give special thanks to these women to trust me to pass on their experience,” she said. “They were strong, they endured a lot of suffering and they are good role models.”

For over fourteen years, Khoury worked in the media field. She was the first Palestinian camera woman, producer and coordinator who covered special events in the Middle East region for the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). In 2000, she established Majd Production Company in Ramallah.

The women’s experiences motivated Khoury to make this film because of their awareness and their uniqueness.

On August 17, 2004, the first day of release for “Women In Struggle,” Palestinian prisoners began a hunger strike. It gained media attention worldwide. As Khoury expressed, they raised their voices for better living and medical conditions within Israel’s prisons.

For example, if a prisoner is in pain, she receives one Tylenol. Visitation of Palestinian political prisoners by family members can be restricted, if not eliminated altogether. For many years, Palestinians endured torture from Israeli prison guards. One additional source of information is a recent article I wrote on this topic.

Years before the 2004 Abu Ghraib prison scandal, Israeli prison guards used these torture methods on Palestinians.

Sometimes peace negotiations involve the release of prisoners. Khoury said the release involves two categories of prisoners: people who snuck into Jerusalem without a permit so they could work or see their family; and the second category involve detainees who will be released from prison within a couple of months because they already served their sentence terms.

Last year, one prisoner refused to leave jail because he did not want diplomats receiving credit for his release. His scheduled release was in a month. The man wanted media exposure on the prisoner issue so that conditions would improve in the prisons.

At the time the women in Khoury’s film were in prison, they did not have political prisoner status. They wanted their status clarified officially and publicly. In the ‘60s and the ‘70s women’s involvement in the political movement was not as accepted within Palestinian society compared to now. Back then, “appropriate” roles for women did not expand into the political realm.

Upon release, these women faced unique challenges regarding marriage and children. Some women could not have children anymore physically – the torture sterilized their reproductive systems. Moreover, the psychological trauma caused by prison torture made it difficult for one woman to have a relationship with her husband.

Their struggles did not stop after their prison

release – they continue to suffer from their prison

experiences. Their integration into Palestinian society is

not an easy transition.

Khoury gained a thorough

understanding of the women’s perspectives so that the film

was from their point of view.

For the last, two months, Khoury toured the U.S. with her film. The Chicago Palestine Film Festival was her last engagement. What has been the reaction of audiences in the U.S. and back home?

“I’ve seen many tears while I screened this film in Palestine,” she said. “I’ve seen tears from Israelis (Jewish people) in the U.S.”

Khoury’s hope is that her film brought public awareness, and that people will continue asking questions about the conditions of Palestinian prisoners. She hopes people will continue learning more about it.

For instance, Khoury shared that 450 Palestinian children under the age of 18 are in Israeli prisons. She explained that life under military occupation is harsh. People see tanks rolling by their windows instead of a peaceful view. People hear the sounds of Israeli helicopters flying overhead.

“We live under force,” she said. “Occupation is the worst method of torture.”

I asked Khoury about a scene in her film that involves an Israeli soldier holding a gun near her and one of the women, Aysha. At the time, Khoury’s main concern was that Aysha not suffer anymore. She explained that Israelis have guns, so they use military force for abuse and humiliation. The Palestinians carry their strength and their power because they have a right to live on their land.

The Arabic word, sirra’ means a struggle that does not finish. Palestinians will continue demanding their human rights and their right to live on their homeland peacefully.

About a year ago, Palestinian filmmakers formed an organization called the Cinema Group (http://cinemagroup.ps), which gathered individual filmmakers into an association for collective communication. The web site has the latest developments in Palestinian cinema.

Khoury’s next film is about the social aspects of Palestinian women. She explained sirra’ means inner struggle, cultural struggle and the social aspects of struggle also.

After the film discussion, several audience members approached Khoury. They asked her more questions and they shared their comments.

From what I could understand, one woman introduced herself, and then said: “I want to thank you so much for making this film.”

While she spoke with Khoury, the woman wrapped her hands around Khoury’s hands.

Sonia Nettnin is a freelance writer. Her articles and reviews demonstrate civic journalism, with a focus on international social, economic, humanitarian, gender, and political issues. Media coverage of conflicts from these perspectives develops awareness in public opinion.

Nettnin received her bachelor's degree in English literature and writing. She did master's work in journalism. Moreover, Nettnin approaches her writing from a working woman's perspective, since working began for her at an early age.

She is a poet, a violinist and she studied professional dance. As a writer, the arts are an integral part of her sensibility. Her work has been published in the Palestine Chronicle, Scoop Media and the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. She lives in Chicago.

Eugene Doyle: Before It’s Too Late - Reimagine New Zealand’s Military Future

Eugene Doyle: Before It’s Too Late - Reimagine New Zealand’s Military Future  Binoy Kampmark: Gender Stunts In Space - Blue Origin’s Female Celebrity Envoys

Binoy Kampmark: Gender Stunts In Space - Blue Origin’s Female Celebrity Envoys Richard S. Ehrlich: A Deadly Earthquake & Chinese Construction

Richard S. Ehrlich: A Deadly Earthquake & Chinese Construction Ian Powell: It Does Matter To Patients Whether They Are Operated In A Public Or Private Hospital

Ian Powell: It Does Matter To Patients Whether They Are Operated In A Public Or Private Hospital Gordon Campbell: On Marketing The Military Threat Posed By China

Gordon Campbell: On Marketing The Military Threat Posed By China Binoy Kampmark: Olfactive Implications - Perfume, Power And Emmanuel Macron

Binoy Kampmark: Olfactive Implications - Perfume, Power And Emmanuel Macron