Fonterra: How Does National Foods Fit?

Fonterra: How Does National Foods Fit?

By Tony Baldwin

Published in the Dominion Post on 13 November 2004

PROPOSED

STRUCTURE:

Click for big

version

''Milk is the business of the dairy cooperative. The co-operative is not an investment company''.

This from a report by Nuffield Scholar and dairy farmer, Catherine Bull, speaks for many Fonterra shareholders.

It is reflected in Fonterra’s Cooperative Philosophy Statement, a key document that defines the principles under which Fonterra is to be governed: “Fonterra’s principle purpose and priority focus is to maximize the sustainable value of supplying shareholders’ milk”.

Catherine Bull again: “Farmers invest in the value-adding chain to secure an outlet and maximise payment for the farmers’ product – milk”.

So why is Fonterra putting up A$1.6 billion of NZ dairy farmers’ money to buy Australia’s National Foods?

Will National Foods process NZ milk? No. Will it use NZ dairy ingredients? Not in any major way. Will it increase the price paid for NZ raw milk? No.

But none of these are Fonterra’s takeover goals.

Its primary aim in buying National Foods – a consumer market business – is to increase returns on NZ shareholders’ capital, not their milk.

NZ dairy farmers must therefore see themselves as ordinary investors in a listed company. They should ask, would I choose to put my money into National Foods? What are the risks relative to expected returns? What do the external analysts say? Do I have better alternative uses for my capital?

Unfortunately, few farmers ask these questions in a rigorous manner. Most don’t see the information holes. Too many blindly assume the National Foods move is about increasing the value of their milk.

The disconnect in understanding between Fonterra’s shareholders and their directors and mangers is stark. The result is ‘soft’ thinking and weak performance disciplines.

Whether the National Foods bid makes commercial sense for Fonterra’s shareholders is hard to tell. Hardly anyone outside Fonterra or National Foods has analysed it for them.

Several institutions will size it up for National Foods’ shareholders, but not Fonterra’s because their shares are not listed.

Contrast this with expansions into Australia by Air NZ, Fletcher Building, Nuplex, Tower, Telecom, Contact, The Warehouse, GPG or Carter Holt, to name a few. External analysts probed these moves, running the numbers, looking at likely impacts on shareholder value.

Some big overseas investments succeed, others don’t. What counts, however, is having a wide variety of people valuing the board’s decisions, backed by the real threat of shareholders selling if they’re not happy.

As eminent economist, Bengt Holmstrom, points out, “stock prices may be imperfect but they easily beat out alternative ways of assessing future potential. Any other man-made measures fall far short of this mark”.

Fonterra doesn’t face these disciplines. Impacts on its share price won’t be signalled for another six months. Even then, it will be the board’s view, based on a single valuer’s opinion.

If Fonterra’s shareholders don’t like the National Foods acquisition, they can’t sell their shares without selling their farm. Their capital is captured.

National Foods is a listed company. NZ suppliers could buy National Foods shares directly if they are such a good buy. Fonterra could return capital to its shareholders and let them make their own decisions.

If Fonterra believes higher returns can be achieved if it buys National Foods, the board should have to persuade NZ suppliers to invest in Fonterra for this purpose.

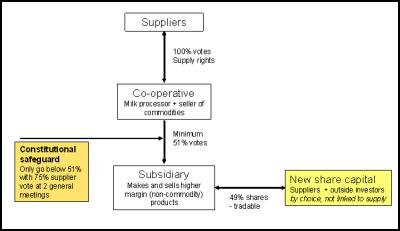

Fonterra should set up a separate company to own and operate downstream businesses like National Foods. It could be 51% controlled by Fonterra. But let NZ suppliers choose to invest in the company or not.

I am not the only person to propose a normal company structure with outside capital for Fonterra’s downstream businesses. Dr Zwanenberg of Rabobank, one of the world’s leading dairy co-op advocates, has recommended a similar structure.

Another approach is the Friesland Coberco model. It is a large dairy co-op in the Netherlands, which now has a separate tradable ‘B’ share, similar to NZ’s Livestock Improvement Corporation. Supplier-shareholders receive dividends separately from milk payments.

A third model is the Kerry Group of Ireland, which converted from co-op to listed company. It has grown into a diversified food ingredients business and increased the value of co-op farmers’ capital from €40m in 1986 to €1,007m in 2004.

It is unfortunate for NZ suppliers that the public part of Fonterra’s current capital structure review excludes an objective analysis of these options.

Fonterra is funding its National Foods bid using debt. If it wins, it will have to wait some years before it can borrow on this scale again to make further acquisitions. Meanwhile, its main rivals – Danone, Kraft and Nestle – are not so constrained. They can raise more equity if required.

In its current form, Fonterra can’t and will therefore lack the flexibility to take advantage of other major value-enhancing opportunities over the next several years.

As Robert Heuer pointed out to the US National Council of Farmer Cooperatives in 2002, "cooperatives can't just build a business on debt. They're going to have to get equity investment, if not from grower-owners then through preferred securities or stocks”.

Fonterra also needs to sort out the function of its share value. It is supposedly used now to signal the value of milk, and therefore whether suppliers should increase milk production. As Fonterra grows its downstream profits, this mechanism will become increasingly less efficient.

A Fonterra share buys future net profits after paying suppliers for milk. So it doesn’t make a lot of sense to force suppliers to buy shares in order to supply milk. Separate contract milk prices are required.

If it succeeds, the National Foods takeover will bring these capital structure issues into sharper relief. Change will become unavoidable. The board will have to confront the growing divergence among its shareholders as the industry’s traditional homogeneity starts to unravel.

For the 15% of shareholders that account for about 40% of total output, concepts like cost of capital, EVA and the NPV of discounted cash flows are basic tools of business. Their focus is on using capital to create greater wealth.

For the 65% of smaller farms producing less than 40% of total milksolids, the business is about milk, not capital. Fonterra is not an investment company.

For the Shareholders Council, “the heart of Fonterra’s cooperative philosophy is the distribution of wealth between shareholders”. The co-op’s socialist roots are still close to the surface.

Fonterra’s problem is that it tries to traverse all schools. As Fonterra’s Graham Stuart claims, “we are a dairy farmers' co-operative. And we are a multinational marketing company. And we are also an international capital investor”.

The result is a kind of commercial schizophrenia that leads to under-performance. It’s time to make structure and strategy fit.

Tony Baldwin

Industry analyst

Leader, Producer Board

Project Team

1999

Ian Powell: A Timely Call For A Social Contract In Health

Ian Powell: A Timely Call For A Social Contract In Health Binoy Kampmark: Bratty Royal - Prince Harry And Bespoke Security Protection

Binoy Kampmark: Bratty Royal - Prince Harry And Bespoke Security Protection Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance

Keith Rankin: Make Deficits Great Again - Maintaining A Pragmatic Balance Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids

Richard S. Ehrlich: China's Great Wall & Egypt's Pyramids Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land

Gordon Campbell: On Surviving Trump’s Trip To La La Land Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?

Ramzy Baroud: Famine In Gaza - Will We Continue To Watch As Gaza Starves To Death?