Tony Baldwin: Fonterra At A Cross-Roads

Fonterra: At A Cross-Roads

By Tony Baldwin

First Published in the NZ Herald, 18 October 2004

The NZ dairy industry is founded on a set of immutable, almost semi-religious, covenants. Like the parishioners of a large church deciding whether to change their creed, the process of change is shrouded in suspicion, politics and delay. “There is no need to rush”, intones current chairman, Henry van der Heyden.

But after 10 years of manoeuvring, the core issues facing the industry remain the same. Fonterra is still tangled in the same knot of contradictions and wishful thinking. And its leaders are still making the same semi-miraculous claims:

Somehow they will fully unlock Fonterra’s higher margin businesses without raising significant new share capital. Returns on share capital will be maximised, as well as the price of raw milk. Extra rewards can be given to higher value farmers, but all suppliers will still receive the same single national average payout. Suppliers will get better price signals, yet dividends and milk price can remain bundled in the same cheque. Fonterra will remain the only buyer of farmers’ shares, but somehow it will also significantly reduce its related balance-sheet risk. And milk volumes will be effectively controlled, but Fonterra will still accept all milk produced.

In a nutshell, Fonterra pretends it can be both an open customer-driven corporate and a closed supplier-driven cooperative, all within a single structure.

These gravity-defying assertions are not credible.

Traditional export-orientated supplier cooperatives around the world are facing the same basic problems: lack of funds, inefficient price signals, divergent shareholder goals, weak performance monitoring, and greater focus on producers than consumers.

These themes recur in commentaries by leading cooperative academics and directors.

Put simply, closed supplier co-ops in consumer markets are at a cross-roads.

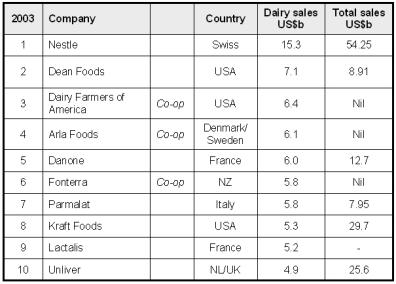

Jens Bigum, head of Arla Foods, the world’s No 2 dairy co-op (ranked above Fonterra in 2003), observed earlier this year that “the dairy sector is seeing an extremely tough elimination race, and we find ourselves competing against global giants like Nestle and Danone, which have very strong capital bases”.

“In order to survive and to pay one of Europe’s highest milk prices, we need a substantial amount equity capital”, Bigum said.

For Henry van der Heyden and his board to claim that Fonterra can unlock the full potential of its downstream businesses without substantially more capital or a separate corporate structure or tradable shares is intellectually dishonest.

If Fonterra is serious about maximising value, its existing pool of 12,000 suppliers is simply not large enough to meet all of its future capital needs.

Nor should suppliers be forced to invest in higher-risk down-stream activities, as they are now.

For Fonterra, it is ‘soft’ money, free of the disciplines of competing for new equity in the capital markets.

For average suppliers, it is a captured investment that can create portfolio problems, where assets are not sufficiently diversified.

It also denies suppliers choice.

To realise it full potential, Fonterra needs to parcel its downstream activities into a normal company structure with tradable shares de-linked from milk supply and pay dividends, not in a milk cheque.

This business is significantly different from milk collection, milk processing and commodity trading. It requires a different strategy, different expertise, different resources and different risk-management.

Capital is the primary input, not milk. Consumers are paramount, not suppliers. Shareholder returns are to be maximised, not the price of raw milk.

All over the world, dairy cooperatives concentrate on commodity and fresh milk products – the low margin end.

The high margin end is dominated by corporates like Kraft, Nestle, Danone and Unilever. There are very few examples of a dairy cooperative succeeding in high margin markets.

So why is the obfuscation from chairman Henry van der Heyden? Because as an alert politician, he knows that, to a large proportion of his 12,000 constituents, words like ‘de-linking’, ‘tradability’, ‘non-supplier investors’ spell doom.

To quote the Dairy Exporter, suppliers believe outside investors would “turn their children into peasants”.

This fear is deeply and widely held. Indeed, it has shaped the industry since its formation in the 1890s.

As industry historians Arthur Ward and David Yerex point out, “unity among farmers emerged from their shared distrust of outsiders”. “Farmers developed a suspicion that city and urban interests were seeking more than a fair share of their hard-won livelihood”.

Though misplaced, this presumption of vulnerability and exploitation still permeates the industry today, and is the reason for the narrow parameters around the capital structure review Fonterra is currently undertaking.

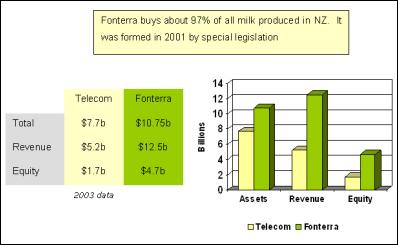

It is also the reason why the industry did a deal with the Government to by-pass normal Commerce Act checks when Fonterra was formed in 2001 – a process that would have assessed whether the economic benefits of forming a near-monopoly outweighed the detriments.

To get an authorisation from the Commerce Commission, Fonterra would have needed to deliver a more progressive capital and governance structure, including some degree of share separation, tradability, stronger performance disciplines and better ‘unbundling’.

Key changes required at Fonterra Contract for milk volumes and durations that match Fonterra’s business plan. The current system of accepting however much milk is produced is not efficient Establish a competitive market price for raw milk for different periods Do not require suppliers to buy Fonterra shares at market value in order to supply. [Among other things, this is because a share buys the net present value of expected future profits after paying for milk. A share does not buy future milk price payments] Separate the milk price from dividends Parcel downstream activities into a separate company with tradable shares de-linked from milk supply. It could be 51% controlled by Fonterra Allow co-op shares to be traded among suppliers within a band (80-120%) of milk volume supplied Sell down about 12% of Fonterra’s milk collection business to get free of Government regulations requiring it to accept all milk produced and supply competitors

Then, as now, these requirements would have cut across suppliers’ deep distrust of capital markets. Hence the 2001 by-pass deal (reportedly brokered by Sir Dryden Spring with Helen Clarke).

In effect, it gave Fonterra a licence to control the rate of its reform. This is akin to delegating to domestic manufacturers the right to decide whether and when to remove import protections.

It enables dairy leaders to defer that which would otherwise be unavoidable. Henry van der Heyden can therefore say with apparent impunity, “there is no rush” – as if delay is costless. It is not.

The longer Fonterra delays, the greater the cost to dairy farmers and the NZ economy.

Five years ago, dairy leaders were saying milk growth was too high and co-op share prices were too low. Now they are saying the opposite. The leadership’s approach is still reactionary, swinging in short term oscillations, responding to perceived supplier concerns, but carefully avoiding the core issues.

The question is not whether fundamental change is needed (see box below) – it clearly is and the leadership knows it. The issue is how to get suppliers to accept change after such a long history of misinformation and mythology.

Exposing the real problems and proposing effective solutions would be a cultural revolution to many suppliers, which is why Henry van der Heyden and his board are so timid.

Fonterra and New Zealand can’t afford to wait for generational change. It is time for the Mr van der Heyden and his directors to inform, to inspire, and to lead.

Tony

Baldwin

Industry analyst

Leader, Producer Board

Project Team 1999

Email tbaldwin@ihug.co.nz

18 October

2004

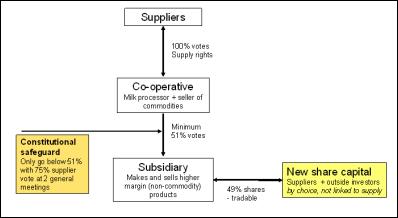

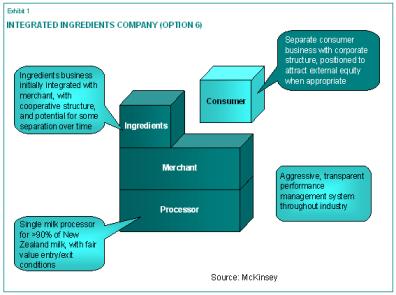

Diagram of 1999 industry plan

Essentially the same for 2001 merger that gave rise to

Fonterra – shows plan to separate consumer business and

possibly ingredients business

2003 World Rankings

Size in the NZ context

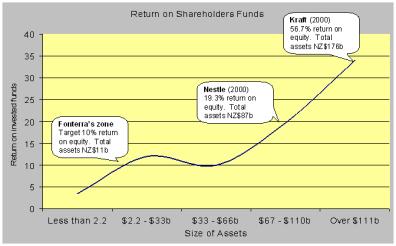

Comparative rate of return

–

Fonterra compared to consumer-focused competitors,

Nestle and Kraft

**** ENDS ***

Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025

Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025 Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship

Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship Binoy Kampmark: The Killing Of Israeli Embassy Staffers - Netanyahu’s Antisemitism Canard

Binoy Kampmark: The Killing Of Israeli Embassy Staffers - Netanyahu’s Antisemitism Canard Keith Rankin: Zero-Sum Fiscal Narratives

Keith Rankin: Zero-Sum Fiscal Narratives Eugene Doyle: Chinese Jet Shoots Down France’s Best Fighter; NZ And Australia Should Pay Attention

Eugene Doyle: Chinese Jet Shoots Down France’s Best Fighter; NZ And Australia Should Pay Attention Ian Powell: “I Can Confirm They Are Hypotheticals Drawn Largely From Anecdotes And Issues The Minister Has Heard About.”

Ian Powell: “I Can Confirm They Are Hypotheticals Drawn Largely From Anecdotes And Issues The Minister Has Heard About.”