Health System Funding Already 'Needs Based'

Health System Funding Already 'Needs Based'

Op-ed piece in Dominion Post 9 March 2004

By Peter Crampton

Need and ethnicity are already co-habiting in our health funding system. ‘Socioeconomic deprivation’ and ‘ethnicity’ feature as two of the five main factors that dictate need and how health dollars are currently spent.

Both factors matter, says the existing system. Not as much as the fundamental measure, population size, nor age and gender, but they are important parts of the equation. That’s the equation that is used when New Zealand calculates our needs-based health funding system. The one we’ve run, in one form or another, for the last ten years. The previous funding system, based on the 19th century location of hospitals, had evolved in a way that unfairly penalised fast growing regions like Auckland.

Fundamentally, our health system is based on the principle that we spend most health dollars on the people who need most care. That allows for everyone to be looked after without bankrupting the nation.

To make that actually work in reality there need to be formulas. Currently, the money flows this way: the Ministry of Health funds District Health Boards using a population- and needs-based formula, ie they get a certain number of dollars per head, adjusted on a ‘needs basis’. The DHBs then fund Primary Health Organisations (like GPs and nurses) using more of the same kind of needs-based formulas.

The main factors that affect the money allocations are:

1. Population size (this gives a base-line ‘per head’ allowance)

2. Age structure of the population (adjustments for greater needs in the old and very young)

3. Gender (adjustments for greater needs in women in their child-bearing years)

4. Socioeconomic deprivation (adjustments for greater needs in people living in socioeconomically deprived areas)

5. Ethnicity (adjustments for greater needs in Maori and Pacific populations).

Ideally it would be nice not to have to use such clunky things as formulas with complicated weightings of generalised factors like these. But in the absence of detailed accurate health data for every person in New Zealand, they are what we have to work with.

Some of the factors used to spread the money don’t generally raise eyebrows. Who would object to the very old, babies and pregnant or new mothers getting more of the kitty. Instead, the focus of recent debate has been on the relative importance of socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity. The calls for the emphasis to be on socioeconomic factors is well-founded: for well over a century, researchers have demonstrated a strong link between poverty and (poor) health – this association is unlikely to go away in the foreseeable future (although needs-based funding should help reduce inequalities).

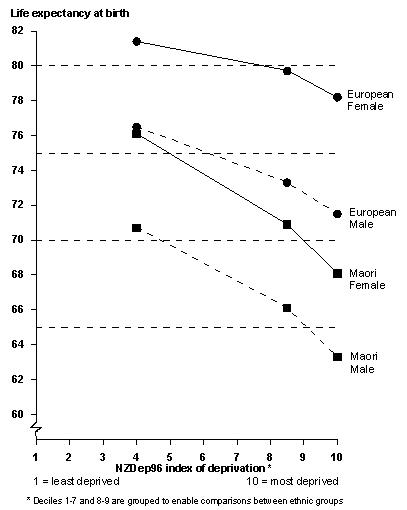

But the recent public debate has tended to miss the fact that in contemporary New Zealand, ethnicity is an important measure of need, even after socioeconomic deprivation is taken into account – see graph showing life expectancy by deprivation and ethnicity. This shows, as also recently reported by Dr Tony Blakely, that Maori people can expect to die earlier than European New Zealanders who have similar levels of socioeconomic deprivation. In the future, hopefully this won’t be the case. Then, when the health status of all ethnic groups is similar, we can drop ethnicity out of the formulas.

In the end the health system can only do so much to change the extent of health care needs – our health status. For that we rely on the economy, high employment rates, the education system, good housing and the myriad other factors that create healthy populations. But we do expect the health system to respond to our health care needs, – it is the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff… and the ambulance needs to be funded to respond to the needs of everyone, and to respond the most to those that have the greatest levels of sickness.

ENDS

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight

Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine

Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor

Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025

Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025 Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship

Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship