Tony Baldwin: Fonterra, Andrew Ferrier’s Challenge

FONTERRA: ANDREW FERRIER’S CHALLENGE

By Tony Baldwin

17 December 2003

Dairy farmers have a long and deep distrust of outsiders. This powerful and well-documented suspicion surfaced on the industry’s birth over 100 years ago. It continues to have a profound influence over the industry’s current structure and future direction.

It therefore came as a surprise to many observers that Fonterra opted for an outsider to take over from Craig Norgate as CEO. An urban Canadian grounded in the sugar business, Andrew Ferrier is neither a farmer nor a Kiwi nor a dairy industry man.

Is this a major cultural break-through? Not really. In fact, Andrew Ferrier’s appointment resumes an old line of foreign leaders.

When ‘King Dick’ Seddon’s Liberal Government was trying to kick start a NZ dairy industry in the 1890s, a succession of Canadians, Scots and Danes were imported to serve as ‘Government Dairy Experts’, organising local co-operatives and teaching settlers how to farm. Three Canadians later held the top job of Dairy Commissioner. (Of course, none ever managed to become the Government’s ‘Instructress in Soft and Fancy Cheesemaking’, a position held by an unmarried English woman).

From this broader historical perspective, there is nothing new in a Canadian running the show. Indeed, the industry’s foundations in NZ were Government-forged, based on American co-operatives using Canadian techniques. Suppliers’ objections are not to outside managers, but to non-farmer share capital. Many also do not trust non-farmer directors.

The salient question is, how will the latest Canadian manager improve Fonterra’s performance?

After a highly controversial start, with the Prime Minister sanctioning special legislation to by-pass normal anti-trust checks (Fonterra’s near monopoly position was highly unlikely to be authorised by the Commerce Commission), Fonterra’s overall performance has ranged from poor to indifferent.

Year 1 coincided with a strong rise in commodity prices and a low NZ dollar, yielding an unusually high payout (at least in nominal terms). The milk Gods seemed to be smiling and farmers felt fortified in their mega-merger decision, despite minnow commodity producer, Westland, outperforming Fonterra. The crescendo of large-scale farm conversions grew ever louder.

Years 2 and 3, however, revealed Year 1 to have been an aberration. While some gains have been made in reducing costs and streamlining logistics, the industry’s fundamentals remain the same:

1. 80% of Fonterra’s revenues come from commodities.

2. Fonterra has very limited ability to influence prices. It is largely a ‘price-taker’;

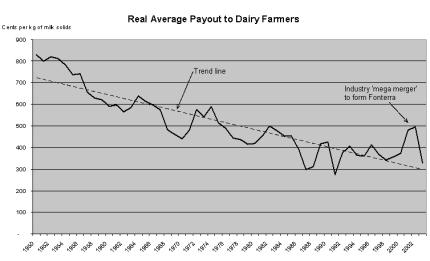

3. Long-run real commodity prices are falling on average about 2%pa;

4. Exchange rates are at record highs. Even at post-float averages, exchange rates would put pressure on Fonterra’s payout;

5. Real payouts to farmers have been steadily falling over the last 50 years and are likely to keep tracking south;

6. Fonterra is largely shut-out of the wealthy North American and European markets. Prospects for more open access are limited;

7. Relative to its global dairy food competitors, Fonterra is small, lacking critical mass to back major on-going innovation in branded consumer and specialised products;

8. Fonterra’s multiple Australian investments are messy and lack a coherent strategy;

9. The full costs, risks and benefits of Fonterra’s much-heralded JVs are still not clear. Despite considerable hype, they account for less than 5% of Fonterra’s value;

10. Fonterra is likely to become capital-constrained as its capacity to fund effective growth from debt and JVs reduces. Its closed pool of 13,000 NZ farmers will not be able to provide sufficient additional equity when it is required;

11. Price signals from Fonterra to farmers remain inefficient;

12. Shareholder monitoring, while better than pre-merger, continues to be wanting; and

13. Fonterra’s capacity to realise its full potential is still constrained by an outlook among many suppliers that has changed little over the last 100 years.

The key question for Mr Ferrier is therefore, can he overcome these challenges?

For now, Fonterra is focused primarily on reducing costs. No doubt, the scope of potential cost savings has yet to be fully tested. While important, this strategy is short-term. More fundamental changes are required to achieve longer-term wealth increases for shareholders.

Fonterra needs to manage more effectively how much raw milk it buys. Fonterra should quickly move away from the traditional obligation of buying all milk produced, which makes the business highly production-driven and akin to a dog blindly chasing its tail. To achieve this change under current law, Fonterra would need to sell-down a small part of its NZ processing business.

Fonterra also needs to manage its risks more efficiently. It should offer farmers a variety of contract options. Fixed quantities of milk at fixed prices. Or certain quantities at fixed prices, but other quantities at floating (seasonal) prices. In some cases, both price and quantity could be variable. Different combinations are possible. Fonterra currently manages many risks by simply averaging across all suppliers. Considerable savings could be made by allocating risks among suppliers more efficiently.

It is crucial for Fonterra to free up its consumer arm, NZ Milk, and equip it properly to pursue more tailored wealth-creating strategies. These are necessarily different in risk-profile, method and focus from Fonterra’s commodity business, NZMP. The need for this fundamental change is well-recognised among Fonterra’s commercial leadership clique. Ever fearful of supplier backlash, however, they continue to re-cycle excuses for delay.

Value signals to suppliers and shareholders need to be significantly improved. In particular, returns on capital need to be separated from returns on milk. Again, Fonterra’s inner cabal is fully aware of this issue but continues to avoid leading real change.

The Government’s ‘Chief Dairy Expert’ in the 1890s trumpeted turning grass into milk as an unstoppable source of ‘white gold’. A myth was born. The ‘white gold’ epithet is still used today by media and PR people.

Unity is another old axiom long heralded by suppliers as their key strength. However, as many industry historians have observed, this putative unity is based on a shared distrust of outsiders, not a common view on how to grow wealth.

Indeed, the very concept of a cooperative dairy company is an extension of dairy farmers’ deep desire, from pioneering days, to exclude non-farmer investors.

These three precepts are rooted like a faith. Farmers’ adherence is unquestioning. It is also seriously misplaced, closing suppliers’ minds to better strategies and structures.

Fonterra’s relative excellence in farm management and commodity production is not in question. However, its ability to achieve appropriate returns on equity and grow shareholder value on a consistent basis is doubtful. In its current form, Fonterra is bound for mediocrity.

Andrew Ferrier’s challenge is to open shareholders and directors to wider wealth-creating horizons. Significant changes are required if Fonterra’s full potential is to be realised.

Tony

Baldwin

Industry Analyst

Attachments:

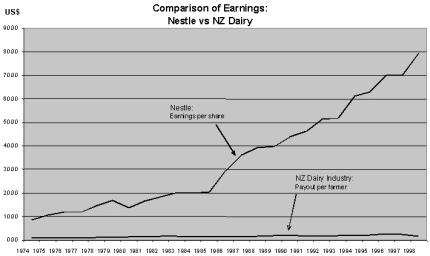

- Graph

comparing Nestle earnings to NZ dairy industry payout

-

Graph of real industry average payouts to dairy

farmers

NESTLE vs NZ DAIRY – CONTRAST OF STRATEGIES

In 1867, Henri Nestle, a small merchant and inventor, created the ‘Nestle’ brand to market his new infant formula using Swiss milk. The brand is now associated with a wide variety of consumer food and beverage products, and represents one of the world’s largest and most successful food companies.

In 1886, Henry Reynolds created the ‘Anchor’ brand. It became synonymous with NZ butter in the UK. The brand continues to be associated with a relatively narrow range of dairy commodities and fits within a modestly successful company selling about 2% of the world’s basic dairy products.

Click for big version

Source: Associate Prof Warren

Hughes, Waikato University

Note: Does not include gains

in the value of Nestle shares or farmers’ land

Click for big version

Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025

Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025 Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship

Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship Binoy Kampmark: The Killing Of Israeli Embassy Staffers - Netanyahu’s Antisemitism Canard

Binoy Kampmark: The Killing Of Israeli Embassy Staffers - Netanyahu’s Antisemitism Canard Keith Rankin: Zero-Sum Fiscal Narratives

Keith Rankin: Zero-Sum Fiscal Narratives Eugene Doyle: Chinese Jet Shoots Down France’s Best Fighter; NZ And Australia Should Pay Attention

Eugene Doyle: Chinese Jet Shoots Down France’s Best Fighter; NZ And Australia Should Pay Attention Ian Powell: “I Can Confirm They Are Hypotheticals Drawn Largely From Anecdotes And Issues The Minister Has Heard About.”

Ian Powell: “I Can Confirm They Are Hypotheticals Drawn Largely From Anecdotes And Issues The Minister Has Heard About.”