SRA Commentary: Pleasant Fictions

SRA Commentary: Pleasant Fictions

By Chris Sanders

October 13

2003

"The currency is severely threatened by the uncontrolled expenditure of those who govern…currency and reserve banking are shaken by the bloated expenses of the state, and will cause the collapse of the national financial structure despite vast efforts and ever increasing taxation…No amount of genius can prevent the ruinous consequences on our currency caused by this uncontrolled policy of spending."

- Memorandum from the board of the Reichsbank to Chancellor Adolph Hitler, January 7, 1939, quoted in Weitz, Hitler’s Banker, Warner Brown, London, 1999, p.244"This is mutiny!"

- Hitler’s Response

Pretty paper

On the 9th of October, the United States introduced a new $20 bill to replace the series 2001 bill of the same denomination. The pretty new bill has peach and blue tones, the first ever to depart from the green and black “greenback” design that has been so successfully produced for a century or so by engravers in the United States, Russia, Lebanon, Korea and elsewhere. Indeed, it is ostensibly because the greenback has been so successfully reproduced that America is bringing out this new note, with enhanced security features that make it more difficult to counterfeit.

Were this just another day in American history, we would not think too much of a new form of currency being brought to market. This is not just any currency however, as the ad campaign associated with it suggests: the government has budgeted more than $30 million for an advertising campaign to push the new bills, which will be followed in the next couple of years by new $50s and $100s.

But the real reason for thinking that the new twenty dollar bill is more (or less, as we shall see) than meets the eye is the financial position of the issuer, the government of the United States. Its net foreign debt, as readers of SRA publications are well aware, is over 30% of GDP and increasing at a rate of 5% of GDP per annum. This is, to put it mildly, a very rapid growth of foreign liabilities. Was it occurring in any economy not able to settle its international obligations at will with the issuance of more paper, that economy would have long since collapsed into recession. The near monopoly that the dollar enjoys as the invoicing currency for international trade (and especially in the trade of oil and gas) and its similar quasi-monopoly on use as an international reserve asset means that the US has not experienced the constraint of actually having to pay for anything. Nothing is free of course, and the US has paid in ways that are more indirect. It has, for example, destroyed much of its domestic commercial industrial base which is needed if it is ever to raise net exports sufficiently to deal with its external indebtedness. And the extreme reliance on debt financing over a period spanning decades has made the economy extraordinarily sensitive to movements in interest rates, making the task of managing the economy very difficult.

This problem is well understood by the managers of America, one of whom, Alan Greenspan, earlier this year suggested that there was no reason to worry about it because foreigners already own so many dollars that they could not possibly allow it to collapse. This is, as the sister of the mad Commodus says to her father Marcus Aurelius in the movie Gladiator apropos of him being a loving father and she a dutiful daughter, a pleasant fiction but nothing more. The rest of the world is most certainly watching the United States with great interest as it wages its military campaign to take undisputed control of the Middle East’s oil fields and wondering how long it can bear the cost.

Wishful thinking

Another analysis of American debt prospects, albeit with conclusions not too dissimilar to Greenspan’s (unsurprising given the connections of the authors with the Fed) was recently published by the National Bureau of economic Research. The paper, entitled An Essay on the Revived Bretton Woods System, posits the novel idea that the international monetary system today is really no more than the old Bretton Woods system. The rationale for this remarkably ahistorical and inimitably American point of view is the proposition that Bretton Woods was intended to revive world growth by creating a system in which the international monetary centre (the United States) opened its economy to other countries whose industrial bases had been ravaged by war to take their exports so that they could rebuild. The US lent long term capital to them to make this possible.

So far, so good. But this has little to do with Bretton Woods per se, which organised the international monetary system in such a way as to make the US accountable for the value of the dollars that it was issuing to pay for European and Japanese imports by making it convertible to gold at a fixed rate agreed by international treaty (the Bretton Woods Agreement). Bretton Woods was thus an international monetary regime underpinned by law. When Richard Nixon closed the gold window at the Fed in 1971, he repudiated not just an international monetary arrangement but also the legal foundation on which it rested. No subsequent international monetary arrangement has enjoyed anything remotely resembling the prestige and widespread acceptance that the Bretton Woods system enjoyed. To ignore this, as the authors of this silly analysis have done, is something that perhaps only an economist, at least a central bank economist, could do.

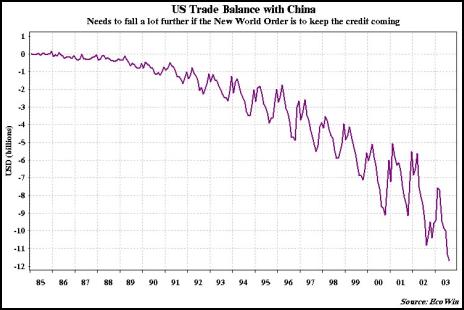

Messrs Cooper, Folkerts-Landau and Garber do, however, have a point. This is that there is no intrinsic economic reason why the US debt accumulation cannot continue, as long as other countries can be found to export to the US and to take American paper to finance that export growth. This, they hopefully conclude, is the role that Asia (and especially China and following China India). Nor is this analysis especially original. We have pointed the same thing out ourselves for several years, but of course our perspective has been informed by worry as friends of America that the price of pursuing such a policy is the destruction of the American industrial base and not incidentally political liberty in the bargain, to say nothing of war.

The real interest of this paper is that it gives an indication of the sort of thinking that is now current in official American economic circles. After all, last winter the administration fired Larry Lindsey, Paul O’Neill, and Glenn Hubbard for pointing out that the War on Terror was going to be too expensive. Since telling the truth is not an acceptable career option, it follows that someone (anyone?) needs to be found to find a way to argue that not only can it be financed, but to show how.

With the administration engaged in implementing the most aggressively regressive tax legislation (in American history?) this exercise in ex-post policy making also needs to find sources of domestic savings. Accordingly, they have been found, and to no one’s surprise, they are “transfer payments,” which is to say Medicare, welfare, social security, and so on. As Greg Mankiw, head of the Council of Economic Advisers put it in International Investor recently, “The real fiscal danger is the entitlement programs.”

Those “entitlement programs” may well be a problem, but this administration will never be able to make the case convincingly. The biggest program (and problem) of all is so-called “defence,” which also makes up the bulk of discretionary spending, and it is defence that is eating up the bulk of taxpayer money. And when contractors working for the Pentagon enjoy cost-plus arrangements with the military and employ large numbers of ex-military employees, which is the entitlement program? In the inverted world of Clinton and Bush’s Washington, it is the programs that are protected by law that are under attack and the discretionary programs that are immune to cuts.What is so interesting politically about this is that programs for the poor have already been gutted over the past twenty years. What is left, social security, Medicare and so on, are really middle class entitlements. When this administration goes for them, it is attacking the very foundation of the domestic political consensus.

This makes the international political consensus even more salient. And it is far from obvious to us that there is much of a consensus in favour of the sort of international financial and monetary arrangements outlined in the Cooper paper. Consider the paper’s proposition that “In spite of growing US deficits, this system has been stable and sustainable.” What planet do these writers live on? We have lived through serial crises ever since the US abandoned the original Bretton Woods architecture.

Political realities

The authors see Asia displacing Europe’s share of US markets, and point to the fall in US yields and contraction of dollar credit spreads as evidence that Asian exporters are reinvesting increased export earnings in the US. This is undoubtedly true, but it does not follow that the system is stable. It has indeed been the system’s instability that has motivated the continental European powers to create the euro as a means of insulating the French and German economies from the shocks associated with American “stability.”

But more to the point is the fact that Asian governments have already accumulated well over a $1 trillion in claims on the American government and the pace of accumulation is increasing. This is a peculiar form of international economic stability which depends on grotesquely large currency intervention over years to keep the currency of the centre country from collapsing. The authors acknowledge that as US debts grow, that “US willingness to repay both Asia and Europe comes naturally onto the radar screen.” Their conclusion is that concerns about growth and the need to maintain it will drive Asian economies (China and India) to continue buying US debt even at low yields, and even in the face of increasing evidence of no intention or even capability to repay it.

This puts us in mind of the British Empire’s similar financial predicament during and after the First World War, when it established a closed currency block known as the Sterling Area, in which Egypt and India exported to metropolitan Britain in exchange for IOUs that they were forbidden to exchange for any currency other than sterling. The sterling area proved to be a leaky one however, because even with the controls in place it proved to be difficult to insulate it from the attractions of the more stable dollar economy of the day.

Today the American equivalent of the

Sterling Area is membership in the International Monetary

Fund which crucially requires that member states eschew the

use of gold as backing for their currency. This is a clear,

if backhanded, acknowledgement by the United States that a

commitment to value and therefore to law is the biggest

threat to the dollar’s position. It would however, be a

mistake to suppose that it is the only one. The increasing

use of another currency or currencies as international

invoicing media would be another. Iraq’s conversion to euros

form dollars for its oil exports was a clear sign that this

is not hypothetical risk, and as we have seen over the

course of the last week such speculation continues to

percolate with respect to Russian oil and gas exports (See

Putin:

Why Not Price Oil in Euros?

). There is simply no

economic reason for Europe to buy oil in dollars, or for

exporters to sell oil to Europe for dollars. Practices that

persist for no good reason tend to be dropped as time goes

on.

And this brings us back to America’s pretty new dollars. These, like America’s attempt to sell its debt further and further afield put us in mind of another historical comparison, which was Hjalmar Schacht’s dual currency system for Germany. Schacht, who was president of the Reichsbank under Hitler, understood that in order to increase the national savings rate and rebuild Germany’s economy and war machine that Germany would have to resort to drastic measures. This was done by creating a two tier currency structure - one for Germans and one for international holders of German obligations. International transactions for vital imports were conducted on a case by case basis and even for barter so as to husband scarce foreign exchange. It was, as those familiar with the German economy know, reasonably successful. But not even Schacht and the central bankers could control a politician who would not be controlled.

If America is not able to induce China and India to become the new “periphery” of the dollar-centric world, a dual currency system may become irresistible. With this in mind, it is useful to examine how easily the US could settle its international obligations. One way of looking at this is to calculate what value gold would have to rise to in order for the US to back its Treasury securities already held by foreigners. The answer is eye opening: as of July this year, $5304 per troy ounce.

The day that Russia does conclude an oil deal with Europe in euros will spell the end of American monetary hegemony and the beginning of a long a painful process in America of increased savings, thrift, and national self-examination. Judging from the laws being passed these days by Congress, it seems pretty clear what the ruling class thinks the result of such introspection would be.

It is hard to avoid the investment conclusion that you should get your money out now, because soon it will be too late.

- Chris Sanders

© SandersResearch.com, all rights reserved.

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight

Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine

Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor

Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025

Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025 Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship

Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship