Chris Sanders: When Winning Is Not Enough

Quick, throw the dice and let me win, and make me rich. I’m badly off. If I had cash, I’d have sense too

- Ape to Mephistopheles.

How happy the ape would be, if he could buy lottery tickets

- Mephistopheles

- Exchange between Mephistopheles and the ape in JW Goethe, Faust, Everyman’s Library, David Campbell Publishers, London 1999, p. 807, Barker Fairly, Transl.

When Winning is not Enough

(Part one of a two part essay on the US and world economy)

Sanders Research Associates – Quarterly Report

One down, how many to go?

Events of the first quarter of 2003 have removed certain uncertainties facing the markets. The most important development is the seizure of Iraq’s oil wealth intact and for all intents and purposes with infrastructure undamaged. There is no prospect of an extended physical bottleneck to distribution and sale at present, unless the war was to widen to include hostilities to Iran. Oil prices have fallen significantly as a consequence, and should remain low through most of next year until the passing of the US presidential elections in November. In the long run, the politics of international oil have changed, probably irrevocably. The US – and by extension its oil firms – is now in a position within certain limits to set prices. Not even before the Second World War was any one party in such a quasi-monopolistic position. The industry will welcome this accession of price stability for its commodity. In the long run, the trade-off for the world economy is likely to be much greater systemic instability.[i]

Widening of the conflict is inevitable. From the perspective of the pro-war clique in Washington, this will be welcome as a continuation of its military campaign. Although as of this writing there is considerable political and diplomatic effort being made to downplay the prospect of war with Syria, the US has cut off Syria’s access to Iraqi oil and is steadily applying pressure. This will continue until Syria capitulates. Whether this actually involves an invasion or not, it will add to the general rise in regional tension. Equally, if not more important, is the fact that the destruction of the secular Ba’ath regime in Iraq has removed any effective counterweight to the growth of Shi’a political and paramilitary power. US prowess in industrialised war, which is primarily a question of mobilising overwhelming firepower, is unsuitable to cope with what is at bottom a political and moral conflict. The implication, as it was in Indochina decades ago, is for a rising intensity and tempo of non-conventional conflict and brutality. This is unlikely to be a short conflict because time is on the side of the forces that oppose the US. It is in their interest to drag it out in order to drive up the cost in both economic and political terms to the US and its allies. The near total embargo on real news from Iraq also means that military action there can be presented as action against “bandits” or other forms of essentially civil disorder rather than what it likely is, the continuation of the conflict as a guerrilla war. This does little to obscure the reality of significant political opposition within and without the region and raises questions about the stability of the American client regimes in Saudi Arabia and Egypt. [ii]

Pay as you go, or rather borrow as you go…

The American government has chosen to finance its regional military deployment in the Middle East on a pay-as-you-go basis over and above its regular appropriation for the Pentagon. Congress has duly approved a supplemental budget of $80 billion, which when added to FY2003’s “defence” budget of $420 billion means that over the next twelve months military spending will top $500 billion. The central government’s deficit will almost certainly rise above 5% of GDP as a consequence. Congress is in the conference stage of resolving differences between a Senate and House version of the administration’s proposed budget, which includes over $300 billion and $500 billion respectively in tax cuts over the next ten years. The budget deficit is likely to head for more than 8% of GDP as a consequence over the next three or four years.

These developments mean that the model for understanding the dynamics of the US and global economy should be changed from that which the markets have been accustomed to use over the last few decades. The conventional model of the US economy is based on erroneous assumptions. Far from being a free market-based system, the US military industrial economy is the largest planned economy in the world. We estimate the unified national security budget (which includes the direct military budget, an estimate for covert operational expenditure, and the cost of administering veteran’s benefits) to be $800 billion. The market capitalisation of the top 50 prime contractors is over $1.5 trillion and growing. The profit dynamics of this considerable market segment are, thanks to the cost-plus terms of business with the Pentagon, such that cost inflation, not cost minimisation, means higher profits for management and shareholders. A not inconsiderable implication of this is that investor preference for minimising workers’ compensation in order to boost “productivity” is based on a mistaken understanding of the economy’s structure. [iii]

In addition, the housing market has been effectively nationalised through the operation of the three government-sponsored enterprises, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Banking System. Legislation passed in the last quarter of 2001 enables Ginnie Mae, which is administered by HUD, to compete with these three for private mortgage and insurance business, making explicit the government connection that was already real, but implicit. When paired with the power of the government to set interest rates through the open market operations of the FOMC, this gives the central government considerable power to impact final demand in the non-military and overwhelmingly service-oriented economy. [iv]

It cannot be emphasised enough that the non-military sectors of the economy exist primarily to serve the national security sector. The distinctions between civil and military are increasingly blurred as ownership in the former becomes more concentrated and more companies become dependent on the latter for the integrity of their bottom line. The national security state has become directly involved in areas not commonly associated with it, as symbolised by the CIA’s excursion into venture capital through its In-Q-Tel venture in Silicon Valley and a multitude of military “contractors” such as Dyncorp, MPRI and others that are in reality nothing but corporative mercenary operations. The boundary between public and private sectors is consequently now so soft that it is impossible to usefully distinguish between the two.

The “liberal” order is anything but liberal

The importance of this digression is that this is a very different economic and administrative structure from that assumed by conventional business cycle theory, and exists precisely because it confers on planners considerable independence from the business and corporate investment cycle. For investors and corporate planners it means that the key variables governing a cyclical rise in interest rates are primarily political. This is probably true in most circumstances, but it is especially so in today’s environment in which the duration and outcome of the War on Terror and the need to finance it are the primary problems facing the nation’s economic managers. This latter point necessarily implies that the priority of the Treasury and the Fed is to ensure that the central government’s borrowing program is adequately funded. This, in turn, means that the Fed is likely to keep interest rates lower and the yield curve steeper than conventional business cycle analysis would suggest is appropriate in order to ensure that the banking sector has sufficient incentive to continue buying government debt. Naturally, the mechanism of the open market process by which the Fed accomplishes this means that it will be required to monetise increasingly large quantities of that government debt.

Because the US national savings rate is nowhere near large enough to fund this projected expansion of borrowing, these developments are very likely to result in a significant increase in the level of net foreign debt and the annual current account deficit. The current account deficit is already over 5% of GDP, and can be expected to reach 8% of GDP or even higher unless the increase in central government debt is offset by a fall in private sector credit demand. Neither experience nor the political objectives of the regime in Washington suggest that this will be the case. The mind-boggling consequence of this is that the country is well on the way to accumulating a net foreign debt of some 60% of GDP, which is double the current level.

This has implications for economic activity and growth elsewhere in the world that are especially pronounced for Asia. It is the willingness of the Asian economies to save and to recycle those savings abroad that makes it possible for the US to even contemplate increasing its net foreign debt from such already high levels. However, those savings are not available for investment and consumption at home, a point that is central to understanding the behaviour of the Asian regional economy in general and the Japanese economy in particular over the last decade. It is clear from the massive and rapid growth in dollar foreign exchange reserves by the Bank of Japan that the Japanese private sector is unwilling to hold dollars, forcing the Ministry of Finance and the central bank to offset private sector dollar sales to prevent a collapse in the US currency. The scale of this operation is unprecedented to our knowledge in economic history. The savings squeeze that the undervalued Japanese currency imposes on the domestic economy is offset by the systematic monetisation of government debt and since the last quarter of 2002 the monetisation as well of a growing proportion of the equity market. All this has resulted in a dramatic inflation of the central bank’s balance sheet to a level today of 25% of GDP, a point regularly noted with appropriately understated alarm by ex-BOJ governor Hayami. [v]

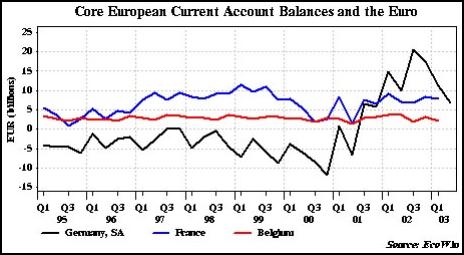

Europe is not unaffected by this situation. International concern generally about the stability of the dollar has grown steadily over the last two years as a consequence of US fiscal and monetary management. The obvious currency alternatives to the dollar should be the monetary units of those economies running the largest net surpluses with the US, which within the major currency group means the yen. The determination of the Japanese authorities to keep the yen from appreciating has meant, however, that investment demand has flowed instead to the euro. The European export and manufacturing sector has suffered in consequence as the euro has risen. One should not overstate this problem however; the European external position is roughly balanced, meaning that the region saves enough to satisfy regional investment demand. And, as is evident from the national statistics within Europe, the industrial centre and political centre of gravity in Germany, France and Belgium continues to enjoy a strong net export position. The notable preference of European investors for bonds has also meant that the fallout from falling equity markets has been more contained than that in the US. Indeed, Europe by comparison is quite stable – boring, perhaps, but stable.

US economic policy is no policy at all

It is clear that the combination of protracted fiscal and monetary easing worldwide should have in normal circumstances resulted in an increase in corporate investment. That this has not happened yet is a function less of purely economic than political policy considerations in the broader sense of the term – concern about the outcome of the US campaign in the Middle East, the consequences for other countries in the region such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt, and the longer term economic complications of a politically driven economic program.

At the top of the list of these complications is the large and growing American net foreign debt position. The estimates that we outlined above would have been thought unimaginable even five years ago and represent a considerable drag on money GDP. Notwithstanding a current account deficit worth 5% of GDP, the US economy is still posting positive real GDP growth – a testimonial to the unprecedented scale of the monetary and fiscal intervention in the economy.

The Bush administration’s preferred policy option of deficit inflation does not represent a solution, which in national terms can only be arrived at by an increase in net exports. This is a circle that cannot be squared, however tight the government’s control over the press and the financial markets may be. It is this essential conundrum that led to the departure of Treasury Secretary O’Neill, White House economic adviser Lindsey, and chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Hubbard. The administration’s policy quite obviously worsens the underlying problems. In this sense it is no policy at all.

The problem is far deeper than that implied between a simple choice of raising or not raising net exports. Expressing the problem this way is, of course, just another way of saying that the country needs to choose whether or not to continue dissaving or to raise net savings, or more commonly, having a recession (more likely a depression) or not. This sounds as though it is simply a matter of opening or closing a valve. It is not so simple, for two reasons. The first is that some sort of currency adjustment, that is to say dollar devaluation, is usually associated with this sort of process in order to make exports more competitive. Although the dollar has fallen over the last fifteen months, it has fallen against the euro, rather than against the Asian currencies of those countries with which the US has the largest competitive imbalances. In official and quasi-official Anglo-American circles, this is usually attributed to a need in those countries for “reform” or “restructuring.” Even more fashionably, Japan is labelled a “structural savings surplus economy.” By this is meant an economy with an aging demographic profile, whose workers need to save more for retirement. The “cure” for this alleged problem is for the Japanese to accumulate even larger current account surpluses to then be recycled to the US. This sort of circular, tautological, and economically inane argument is nothing more than an abandonment of economics, in this case equilibrium theory, in favour of politics, that is the need of the American National Security State for finance.

The second reason why increasing net exports may not be so easy is also more straightforward: the US civilian economy produces very little that the rest of the world wants to buy. Decades of competition with subsidised military contractors have gutted the civilian industrial base. The decline of civilian production has been accelerated with the introduction of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which ratified a process that was already well in train. The euphemism coined years ago, “the information and service economy,” is in reality just a blind to conceal – in plain sight – the transfer of political power and earnings from labour to capital generally, and in more specific terms from production to finance.

Finance and war: two sides of the same coin

It is consequently no accident that American industry has converted production to military – that is to say, subsidised – uses, and in its “civilian” businesses have become, for all intents and purposes, banks. This is the case in autos, aircraft, electronics, machine tools, computers, shipbuilding, and construction. If you doubt this consider: where do Boeing’s civil aircraft business, GM and GE really make their money? Is it manufacturing 777’s, cars and aircraft engines, or is it in financing those businesses through their captive leasing subsidiaries? None of these industrial companies is in reality in the business of producing anything but collateral for their finance arms. This explains in part why they have trouble competing with foreign producers, and care little where their product is manufactured.

The government in recent decades has altered the tax system dramatically. Tellingly, war-inspired “innovations” such as the income tax have not been repealed, or even rolled back with the end of the Cold War, but have rather become more regressive. The Bush administration’s tax legislation may be the latest blatant example of this, but when viewed in its historical context it is the culmination of a thirty-year trend in public finance. What is remarkable is the apparent public acquiescence to the abolition of taxes on capital, and even more remarkable, the public’s acquiescence to the diversion of tax revenue to the military and its allies in industry. If all the administration’s proposals are adopted, the only meaningful taxes left in the United States will be on wages and consumption. This obsessive focus on profit maximisation at labour’s expense has resulted in the export of a considerable proportion of the nation’s supply chain abroad. The propaganda rubric under which this has been “sold” to the market and investing public is globalisation and its alleged economies of scale. This one-world utopianism is supposed, as its supporters such as Intel’s Andy Grove have claimed, to reduce the risk of war. In reality, it has not only raised the risk of war, but in our opinion has made it inevitable.

These developments spell the end of the great twentieth-century guarantor of American political stability, the middle class, and its allied political manifestation invoked by Nixon thirty years ago, the silent majority. In recent decades the political allegiance of this amorphous group in the political centre has been secured by sufficiently large fiscal transfers through the social security and Medicare programs. Not incidentally, the military itself has become, and is touted by its promoters as, a dispenser of social engineering through its training programs and socialised welfare system.

It is tempting to imagine that the government does not understand this process, and that it is susceptible to moderation or even program reversal through the established political system and institutions. This seems unrealistic. Neither the overwhelming support in Congress for the status quo or the immense concentration of power in the establishment media suggest that there is much support within the ruling establishment for reform.

Step lively, Massa’s back in town

On the contrary, the draconian legislation enacted with such haste after the destruction of the World Trade Center in the form of the USA Patriot Act and its successor legislation, The Domestic Security Enhancement Act of 2003 (known on Capitol Hill as Patriot II), betray quite a different approach to maintaining social “stability.” In combination, the two pieces of legislation effectively repeal the Bill of Rights for American citizens and assert an aggressive extension of American “legal” authority beyond US borders.

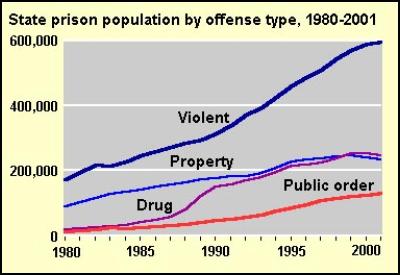

Like the changes to the tax system proposed by this administration, this is not – certainly in retrospect – as surprising or as sudden as it at first seems. Under the guise of the War on Drugs, the government has long since pioneered mass incarceration, with the prison population rising steadily for thirty years to its present level of over 2 million inmates. Even this understates both the nature and the size of this phenomenon, since another 4 million people are in the penal system through probation programs. That this has passed virtually without note outside of a fairly rarefied group of political activists is in our opinion due to the lopsided racial composition of those imprisoned to date, which places the issue in the minds of the predominately white political centre well within the bounds of “law and order” matters and therefore acceptable. Through the extension of asset forfeiture activity, and the establishment of legal precedent supporting it through the successful defeat of challenges to it in the Supreme Court, the government has also been successful at raising significant amounts of cash to finance these activities outside of the constitutionally empowered legislative process. Finally, the increased militarisation of civil law enforcement has established precedent through custom and usage for the direct involvement of the uniformed military and allied intelligence services within US borders. The fact is that the two pieces of legislation noted above merely build on this experience, which can only have encouraged the government to believe that they would be tolerated.

This places the US in a league previously dominated by National Socialist Germany, the Soviet Union and Communist China. This is a matter of statistics, not subjective interpretation. As a fact subject to analysis, it strongly supports the hypothesis that the US National Security State has opted for incarceration as both a tool for social and political control and as an economic safety valve for employment in an economy long since removed from production. This is not as conjectural as it may seem. When adjusted for its prison population and larger military, US unemployment rates are not far off those of other “struggling” industrial countries. In addition, the government continues to pour more money and resources into the War on Drugs, to which it has now added the War on Terror. This can only be expected to add to the pool of labour behind bars, the employment of which is encouraged by both state and federal governments that allow the contracting out of prison labour for uses ranging from digging ditches and shrink wrapping software for Microsoft to assembling aircraft wings for Lockheed. Simultaneously, the privatisation of prison management has been pioneered at the state level and is now being replicated by the federal government, allowing the flotation of the prison labour system on the stock exchange. This allows the managers of the system to create a multiple on prison management that is subsidised by public, that is to say taxpayer, guaranteed bond issues for prison construction and management. Of course, this technique was long since pioneered by military contractors such as Lockheed, who have been able to translate taxpayer subsidy into a stock market multiple that amplifies the return on the margin guaranteed by the Pentagon’s cost-plus contracting practices.

With all this in mind, what is surprising is not that the US has run into such difficulties in attracting international support for its policy, but that international opposition does not appear to have been more widespread, determined, and robust.

Islam, a faux enemy

Because of the overwhelming predominance of Islam in the Persian Gulf and Caspian basin regions, much ink has been spilled over the last twenty years arguing that what is in fact a struggle to control the world’s hydrocarbon reserves is instead a “clash of civilisations.” This does not stand up to scrutiny for very long, but it has had a long shelf life as propaganda goes thanks to the struggle for Palestine and the increasingly close strategic and military collaboration between Israel and the US generally and more specifically between the Sharon wing of the Likud party and the Reagan-Bush neoconservative faction in the US. This has led to a great misunderstanding about the nature of the problem in the Middle East and the portrayal of what is essentially a pragmatic and self-interested desire to control local resources locally as religiously inspired fanaticism. Fanaticism knows no borders or religious affiliation, as the manipulators of illegal Israeli settlement and the religious right in the United States know full well.

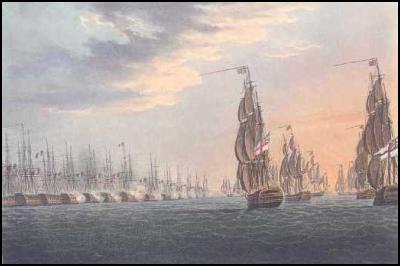

A better model for understanding today’s events in the Middle East is as a continuation of politics by other means in the more familiar arena of great power politics, as the major political and national groups in the industrial world vie for advantage against the backdrop of oil production that has peaked everywhere in the world except for the Persian Gulf. This is a conflict with antecedents that predate Napoleon, and pits what Oswald Spengler called continental Culture against Anglo-Dutch Civilisation. Spengler, writing during the First World War, ascribed Napoleon’s attempt to conquer an empire to a – possibly unconscious – French need to counter British imperial expansion with a French empire of their own. Presciently, Spengler forecast a 21st century European economic union that would echo Napoleon’s failed attempt.

The Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798 ended French hopes of an Indian empire

The Anglo-Dutch model was one built on finance, just as the Anglo-American model is today. That financial model grew directly out of the military needs of imperial expansion, which were hindered by the poor credit quality of the state. The invention of central banking bridged that problem by creating a mechanism whereby the credit quality of the state was swapped for the credit quality of the owners of the central bank, unlocking a pipeline to hitherto unimaginable financial backing for the military ambitions of the sovereign.

The contemporary United States represents the apotheosis of this innovation. In the process of perfecting it, the US has finally buried the political and social legacy of the Scottish Enlightenment that inspired the constitutional formation of the United States in the first place and has erected the National Security State, a perfectly tautological construction that exists only to protect itself. This is nothing more than a political construct whose raison d’être is the justification of the spectacle of capital accumulating capital solely for the sake of capital accumulation in a self-referential, philosophically and ultimately even materially pointless and self-destructive process. America’s leadership may not only bury its Enlightenment heritage but itself in the bargain.

- Chris Sanders

FOOTNOTES:

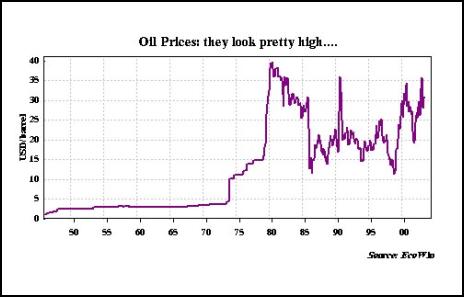

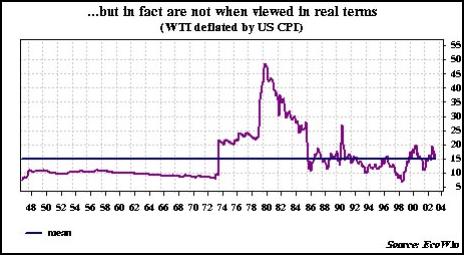

[i]Although oil prices have

recovered sharply, apparently in reaction to the failure of

the Americans to bring Iraqi production back on stream in a

timely and effective manner, it is noteworthy that they have

traded firmly around $30 a barrel. Real oil prices are in

fact in line with their long term average price. Stability

indeed.

[ii]Israel has assiduously promoted a widening of the conflict. Prime Minister Sharon is a regular fixture at the Bush White House, most recently visiting in early August to push action against both Syria and Iran. Indeed, it is becoming hard to separate Israeli from American interests, as a visit to the American Israel Political Action Committee web site demonstrates.

[iii]On the other hand, it is just as likely that investors understand this point all too well and just do not care.

[iv]By the Federal Reserve meeting in August, this had become abundantly clear. The Fed was at pains to emphasise that interest rates would stay low for a considerable time. With record government borrowing to finance, the Fed really has no choice.

[v]The Bank of Japan’s willingness to inflate Japanese foreign exchange reserves in support of the dollar is unprecedented in the history of central banking. The practical effect is to fix the dollar yen exchange rate. When combined with the Chinese currency peg to the dollar, the result is that most of the world’s economy is tied to two currencies, the US dollar and the euro. The American view of this is possibly best expressed by Stephen Roach of Morgan Stanley, who recently published an article supporting the Chinese currency fix to the dollar. Roach points out that Chinese exports have grown so robustly because of a massive influx of foreign capital to China, and that a cheap Chinese production base is essential to safeguard that investment. A more candid expression of the corporate view could scarcely be imagined.

© Sanders Research Associates 2003, republished with permission.

Eugene Doyle: The West’s War On Iran

Eugene Doyle: The West’s War On Iran Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia

Richard S. Ehrlich: Deadly Border Feud Between Thailand & Cambodia Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism

Gordon Campbell: On Free Speech And Anti-Semitism Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal

Ian Powell: The Disgrace Of The Hospice Care Funding Scandal Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest

Binoy Kampmark: Catching Israel Out - Gaza And The Madleen “Selfie” Protest Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels

Ramzy Baroud: Gaza's 'Humanitarian' Façade - A Deceptive Ploy Unravels