SRA Commentary: War As You Like It

Sanders Research Associates

SRA Commentary: War As You Like It

By Chris Sanders

May 12,

2003

"Our species, let us accept it, is entering its phase of socialisation; we cannot continue to exist without undergoing the transformation which in one way or another will forge our multiplicity into a whole. But how are we to encounter the ordeal? In what spirit and what form are we to approach this metamorphosis so that in us it may be hominised?This, as I see it, is the problem of values, deeper than any technical question of terrestrial organisation, which we must all face today if we are to confront in full awareness our destiny as living beings, that is to say, our responsibilities towards 'evolution'."

- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Future of Man, Harper and Row, New York, 1964, p.42.

"We will tolerate substantial income inequality."

War As You Like It

Markets have not yet absorbed the realities of the new war. This is particularly true of equities, which have behaved since the "end" of the Iraq campaign as though it was all over. It is not over. Only the imposition of censorship disguises that fact. Once the American military killed a few journalists, serious coverage of its activities in Iraq ended. That is all there is to the end of the campaign. The war goes on, moving into another stage in which American forces focus on cementing control over the region. Donald Rumsfeld is fond of using the experience of Afghanistan as the model for what the world can expect in Iraq. The war continues in Afghanistan, and in spite of the imposition of a puppet regime in Kabul, the US controls very little of the country. For once we agree with Rumsfeld. That is very likely to be the outcome in Iraq.

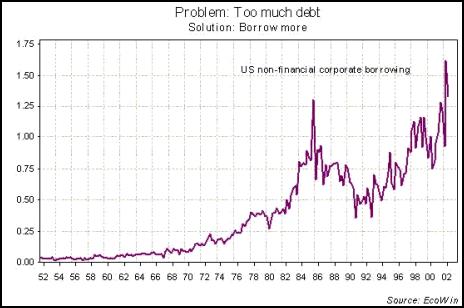

War is being sold, if that is the right word, on the basis that it is good for business and for the market. This is simply wrong. Nothing could in fact be worse. America's apparent offensive is in fact defensively inspired and even desperate. It is a bald attempt to reinvigorate the post World War II international order, collapsed under a mountain of debt. It is, in short, being waged to preserve relative American power. This is doomed to failure, but saying this is not to say that its boosters in Washington, London and Jerusalem are going to be losers, either.

The real losers are what the political left has always called the masses, which is to say labour. The problem in economic terms is an old one, but the current level of economic discourse is so impoverished that it is seldom discussed, much less analysed. This is too bad, because current developments threaten not just labour, but the markets themselves.

The problem is the age-old conundrum of wealth and income distribution, which contrary to the self-advertisement of the neo twins, "neo-liberalism" and "neo-conservatism," has not been solved in the United States or anywhere else. In modern economics, terminology is just the first of the difficulties encountered by the serious analyst. Neo-liberalism refers supposedly to the exponents of modern global market capitalism, while neo-conservatism might well be characterised as its military wing. The point here is that there is considerable overlap between the two groups, which as in so many facets of the new world order, is nonsensical locution. How one can be liberal and conservative at the same time is a contradiction that does not seem to disturb the smug editorial staff at organs of the press that could be fairly considered to be the propaganda instruments of the of this new order, which is neither new nor endowed with much order.

One man's deflation is another's falling income

Recognising the problem is a fundamental prerequisite for understanding the behaviour of the modern international economy. If one denies the increasing disparity of wealth and incomes then one need not be troubled by its deflationary consequences. Yet fear of deflation in recent years has become the bugbear of the markets. But deflation as the markets appear to understand it is just another of the order's tautologies. The assertion is this: profits are threatened by poor pricing power so costs must be cut. The costs that are cut, of course, are labour costs. This most emphatically does not include management compensation, which has soared in recent decades. With labour incomes stagnant or even falling, it is no wonder that demand for products falls behind, and in turn creates a new cycle of cost pressures and job cuts. In formal terms, the problem is that New World Order economics does not recognise or acknowledge that one man's cost is another man's income.

In the global economy, this can be expressed as an identity, Y = W, or income equals wages. In order for there to be demand, workers must be paid so that they have the means with which to express that demand. If profit, and by extension capital accumulation is supported by lowering wages, than eventually the circulation of money between income and wages will fall to zero. Capital, accumulating with nowhere else to go, will be diverted to investment in paper, which is to say on claims on future income. This is the same as saying that it will be diverted to claims on future wages. This is the real source of deflation in the modern global economy, not the wages of workers. In an idealised economy this could not continue indefinitely or perhaps even for very long, as investment in new productive capacity would fall to bring supply and demand back into alignment.

We do not, however,

live in an idealised economy, let alone an ideal one.

Indeed, it is hard to recognise the economy of the textbooks

even remotely in the real political economy of life. In the

textbook economy the United States would have long since

adjusted to the debt accumulation of the cold war years and

raised national savings and net exports. In the textbook

economy trade would be free and access to vital resources

would be taken as a market and price guaranteed fact of

life. In the real economy, world wars have been fought over

just this point, and the War on Terror has just had its

first real macro economic impact: the US has now become the

monopoly price setter in the international petroleum

markets.

If you can get away with something once, why not twice?

In our last issue of Commentary we revisited our expectations for the growth of the US net foreign debt and government deficit. We have been frequent critics of US economic leadership for the reason that the American failure to deal with its dependence on foreign borrowing constitutes a large and growing weight upon the international economy and is the premier source of international instability. The US failure to deal with this has been puzzling and has led us from time to time to deride administration economic plans as no plans at all.

"Bush announces that Japan will buy next century of US National Income"

A clearer picture is emerging however, of what American intentions might be. Disquietingly, it is more of the same - a lot more of the same. We have in previous issues discussed the effects of the Basel bank capital adequacy standards, one of which has been to enable a vast increase in the leverage permitted the largest international, and especially American, banks. Now the American economist Robert Shiller has published a book The New Financial Order, which proposes six "ideas for a new financial order." (Be sure to read the forthcoming SRA review of Shiller's book by Anne Williamson) Shiller's six ideas, which are for such modest things as livelihood insurance, GDP swaps and markets in national income (yes you heard right, markets in long term claims on national income) which boggle the mind. Not, mind you, because of their thoughtfulness, originality or even exposition, but rather for the opposite.

For Shiller, the concentration of financial power represented by the structure of the modern financial industry is the apogee of human development. Facts are no impediment to his post-intellectual mind, which sets the stage with that most fashionable device of the New World Order literati, a thought experiment. Imagine, Shiller invites us, to think of what the world might have been had we had such "innovations" at the end of the Second World War. That what we have, which is an increasingly unstable financial and political system, is of no consequence to this man, who dismisses Enron, Long Term Capital Management, and the stock market debacle of 2000 as aberrations instead of the evidence of systemic dysfunction that they really are. The linkage of these events to the innovations he praises is simply dismissed out of hand. In Shiller, the New World Order economics profession has found its Michael Ledeen.

The Ministry

of Kleptomania

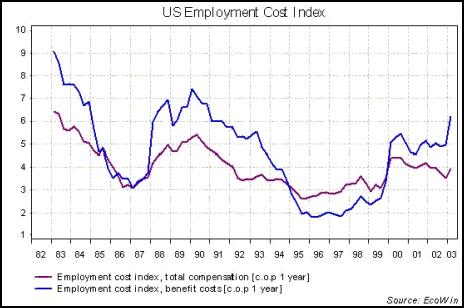

This should terrify anyone with a net worth of under a quarter of a billion dollars because what it represents is a faux intellectual blueprint for institutionalised kleptomania coming out of the heart of American academia, Yale University. Shiller understands this. In his introduction, titled The Promise of Economic Security, he tries to cloak his real intentions by staking claim to the moral high ground. What we are to read, he tells us with typical modesty, is a way to bring economic security and life fulfilment to all. He wastes no time, however, in reassuring the trustees of Yale and others who might read this and wonder if Shiller's career should be deep-sixed. "We are thus concerned about all people's lives, and not just the poorest," Shiller intones. "We will tolerate substantial income inequality." There is thus no danger of mistaking exactly for whom Shiller is shilling. He needn't worry about the Bush family or an invitation to a midnight session at the Skull and Bones Society's crypt on the Yale campus. This is not hot air. Unemployment in the United States has risen to 6%. Corporate profits are recovering, but this is happening through cost reductions, not due to strong demand. Now this is not in itself necessarily a bad thing. Early in a recovery one would expect business to be slow in hiring. But the Employment Cost Index has risen, with benefits inflation surging. That old bugbear, rising health costs, is leading the way.

Class War redux

The international situation deteriorates almost by the day. Though the Middle East receives the lion's share of attention these days, Latin America is equally troubled. In Cuba, where a thaw in political life was discernible, a crackdown by the regime has put an end to it. This was inevitable, given Washington's escalating rhetoric, and the increasing problems elsewhere in the region. With the examples of Afghanistan and Iraq before them, no one on the Pentagon's hit list could conceivably afford to relax.

The point here is that the market wants to believe good news right now and is in a mood to give almost any development the benefit of the doubt. But situations like this usually are a consequence of market positions, not fundamental valuation. Our inclination is to think that after three years of market declines, there must be a lot of shorts. They have to contend with a president determined to win a second term in 2004, a Federal Reserve Board that is equally determined to accommodate whatever financial leverage he demands to get it, and an oil industry that is now in a position to set prices. A short squeeze could well be protracted, and take the market surprisingly high.

But not too high, we would venture. War may make for cool photo ops, but the chickenhawk in the White House has started one that is not about to end any time soon, and is going to be a drain on manpower and resources for years to come. Even if he were to lose in 2004, the two Democrats most likely to face him, Lieberman and Gephardt, have run both flags up their halyards, American and Israeli. Electing a democrat is not going to change the things that count. What counts is that there is nothing yet on the horizon to suggest that the trends toward greater national and international wealth and income concentration are going to reverse, the implication being that demand will continue to stagnate. This will continue to be offset by low interest rates and super-accommodative monetary policy. It would be wrong to think of this as deflationary, though. More accurately, it is the essential precursor for hyper-inflation. What is at issue really is how the big blocks of the industrial world, the US and Europe, position themselves for relative advantage. And it may be in ten years time that we all look back on this and remember it as having been the time when the first shots in a new class war were fired. Because the truth is that the "masses" are being left with very little choice in the matter. Sometimes you just have to fight. Whether you want to or not.

© Sanders Research Associates 2003

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide

Eugene Doyle: Writing In The Time Of Genocide Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight

Gordon Campbell: On Wealth Taxes And Capital Flight Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine

Ian Powell: Why New Zealand Should Recognise Palestine Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor

Binoy Kampmark: Squabbling Siblings - India, Pakistan And Operation Sindoor Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025

Gordon Campbell: On Budget 2025 Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship

Keith Rankin: Using Cuba 1962 To Explain Trump's Brinkmanship