Report: health inequalities are narrowing

Embargoed until 6pm

Media Release

22 August 2007

Report indicates that ethnic and socio-economic health inequalities are narrowing

A new report released today indicates for the first time that inequalities in health between ethnic and income groups in New Zealand may have begun to stabilise and even decrease, the Director-General of Health Stephen McKernan says.

The report: Tracking Disparity: Trends in ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, 1981–2004 has been jointly published by the Ministry of Health and Otago University, Wellington. It is the fourth in the ‘Decades of Disparity’ series on ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in mortality in New Zealand.

Stephen Mckernan says in the 1980s and the 1990s inequalities in mortality (death) rates between Maori or Pacific peoples and the European ethnic group increased steeply.

"Significantly the new report shows that between the late 1990s and the early 2000s the mortality rate ratios appear to have stabilised and the differences in mortality rates between Maori or Pacific and European ethnic groups have narrowed. What's more, it appears that the mortality rate ratios between low and high income groups in New Zealand are no longer increasing as rapidly as they did in the past," Mr McKernan says.

"These findings represent a turnaround of major importance if future monitoring confirms the change in trend. Yet Maori mortality rates remain double those of the European ethnic group, even if the difference is no longer growing. Clearly, there is no room for complacency if we are serious about reducing inequalities in health."

The Ministry of Health has a Reducing Inequalities programme, which aims to raise awareness of health inequality and provide District Health Boards (DHBs) and the wider health sector with skills and tools to assess, understand, and ultimately reduce these inequalities.

"We are working closely with the four DHBs with the largest health inequalities: Northland; Lakes; Whanganui; and Tairawhiti, to ensure that their activities are informed and focused on reducing health inequalities within their districts.”

It will be important to continue monitoring health inequality trends over time especially now that it looks as if a turning point may have been reached, Mr McKernan says.

Tracking Disparity: Trends in ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, 1981–2004 will be available on the Ministry of Health website at: http://www.moh.govt.nz/publications

ENDS

Questions and Answers

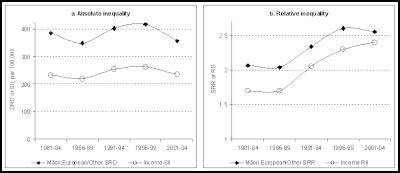

What are the key

findings in the report?

Both ethnic and

socio-economic inequalities in mortality appear to be no

longer widening rapidly, as was the case from the mid 1980s

to the late 1990s. Instead, when measured on an absolute

scale (ie the difference in mortality rates), both ethnic

(Maori: European and, to a lesser extent Pacific: European)

and socioeconomic inequalities in mortality stabilised or

possibly declined between the 1996-99 and the 2001-04

periods. When measured on a relative scale (ie the ratio of

mortality rates), ethnic mortality inequalities stabilized

while the socioeconomic (income) mortality gradient

continued to steepen, but much less rapidly than in the

1980s and 1990s (please see figure below).

It appears likely that the decades of increasing health inequality may be largely over. However the evidence that a turning point has been reached is based on comparison of two timepoints only (ie comparison of 1996-99 with 2001-04 ); analysis of the 2006-09 cohort will be needed before we can be certain that a real and sustained change in inequality trend has occurred (this analysis will only be possible in 2012).

Figure Summarised presentation of estimated trends in absolute and relative inequality in all-cause mortality, 1981–2004, all ages (1-74 years) and both sexes combined

Click to enlarge

Notes for figure:

The

left hand chart shows absolute mortality inequality (SRD for

ethnic and SII for income inequality). SRD is the age

standardised mortality rate difference. SII (slope index of

inequality) is the regression-based equivalent of the SRD,

standardised for both age and ethnicity.

The right hand chart shows relative mortality inequality (SRR for ethnic and RII for income inequality). SRR is the age standardised mortality rate ratio. RII (relative index of inequality) is the regression-based equivalent of the SRR, standardised for both age and ethnicity.

[SII and RII are better measures of inequality than SRD and SRR respectively, as they take into account changes in the sizes of the groups. However, these measures can be used only for groups that are ranked (eg income groups)],

While inequalities in mortality across income bands stabilised from 1996-99 to 2001-04 (on an absolute scale) for all ages pooled (within the 1-74 age range included in the study), this was not the case for young adults (25-44 years) of both sexes. Instead, for low income young adults there was little if any decline in mortality over the whole observation period (1981-2004), compared with a steep decline for their high income counterparts. So for young adults the income mortality gradient steepened steadily with no evidence of a recent slowing, unlike other age groups.

What else does the

report look at?

The report also examines the

contribution of different conditions to the trends in

mortality disparity between Maori and European/Other ethnic

groups (Pacific and Asian ethnic groups were excluded from

this aspect of the analysis due to small numbers, resulting

in insufficient statistical power), and between income

bands. Cardiovascular diseases were found to be still the

major contributor to both ethnic and income mortality

disparities, but are declining in importance, with cancer

(both tobacco-related and nontobacco-related) making an

increasing percentage contribution over time. Suicide has

recently emerged as an important contributor to Maori –

European/Other mortality inequality among male youth.

The report further finds that socioeconomic differences (including differences in income, education, labour market position and so on) explain at least half the Maori: European disparity in mortality (Pacific and Asian ethnic groups were once again excluded from analysis, and for the same reason as above). Also, at least half of the widening in the Maori : European mortality disparity from the mid ‘80s to the mid ‘90s appears to have been mediated by the corresponding widening of social inequalities that occurred over this period (especially in relation to the labour market).

Whether the subsequent possible narrowing in mortality disparity (when measured on an absolute scale) from 1996-99 to 2001-04 was in turn mediated (at least partially) by narrowing socioeconomic differentials cannot be determined from this study.

Why does a person's ethnicity influence health

inequalities?

Inequalities in health exist between

ethnic groups and social classes in New Zealand. In all

countries, socially disadvantaged and marginalised groups

have poorer health, greater exposure to health hazards, and

less access to high-quality health services. In addition,

indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities tend to have poorer

health. Tracking Disparity does not identify what it is

about ethnicity that accounts for its influence on health

over and above its association with socio-economic position.

Other evidence (including work carried out by the Ministry

using data from the 2002/03 New Zealand Health Survey)

suggests that discrimination may be an important cause for

ethnic inequalities in health. Lifestyle behaviours such as

smoking may explain a small part of the inequality. Genetic

or biological differences are not viable explanations for

the trends in ethnic inequalities (further information is

cited in the report).

Is this the first report of its

kind?

This is the fourth report in the “Decades of

Disparity” series, which monitors health inequalities in

New Zealand during the 1980s, 1990s, and now the early

2000s. The first report in the Decades of Disparity series

examined ethnic inequalities in mortality, while the second

investigated economic inequalities, focusing in particular

on differences in survival chances between income groups.

The third report analysed interactions between ethnicity and

socioeconomic position in shaping survival chances, and

quantified the extent to which ethnic inequalities in

mortality are mediated by differences in socioeconomic

position. These first three reports covered the period from

1981 to 1999 – a time of great social and economic change

in our country The current (fourth) report updates the

earlier series to include the period from 2001 to 2004, thus

examining trends in inequalities over nearly a quarter of a

century. It is designed to stand alone, so that readers do

not necessarily need to refer back to the earlier reports in

the series.

What information was used to develop the

report?

Tracking Disparity: trends in ethnic and

socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, 1981-2004 links

mortality to census records for New Zealanders aged 1 – 74

years for the three years following each of the 1981, 1986,

1991, 1996 and 2001 Censuses, in order to analyse ethnic

and socio-economic differences in mortality rates, and to

estimate how these inequalities have trended over the 1980s,

1990s and early 2000s. This report is the fourth in the

‘Decades of Disparity’series of monitoring reports, and

updates the earlier reports.

It is important to emphasise that the apparent change in trend direction is based on a comparison of two timepoints only: 1996-99 compared with 2001-04. We will need to wait for the next update, covering the 2006-09 period – expected in 2011 or 2012 – before we can be sure that a real and sustained turning point in ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in health has been reached.

Why are the findings in the latest report

significant?

This latest monitoring report has shown

that ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities in mortality may

no longer be growing as they have been over the past two

decades or so. While this is grounds for cautious optimism,

these inequalities still remain at an unacceptable level

even if they are no longer rapidly increasing. The results

presented in this report should motivate the health sector

and others to continue working to reduce social inequalities

in health in New Zealand. The challenge of reducing

inequalities in our society continues.

Are there areas

that we still need to focus on in health?

This

latest monitoring report shows that we are going to have to

target cancer prevention and treatment in particular, as

cancer will make an increasing relative contribution to

health inequalities in future. At the same time, we must

maintain and even accelerate the dramatic progress that has

been made in reducing cardiovascular disease among

disadvantaged groups – especially as we face an obesity

and diabetes epidemic that is affecting these groups more

severely and could potentially wipe out the gains we have

made over the past decade. Another focus of attention will

need to be young adults, for whom mortality has not declined

for the low income group. Also, the recent decline in

mortality has not been as dramatic for the Pacific than for

the Maori ethnic group.

Do we still need to focus on

reducing inequalities?

Yes. Ethnic and

socio-economic inequalities in health, and the contributions

of deprivation and discrimination to these inequalities,

should continue to be monitored both nationally and at DHB

level. This will enable us to see whether the apparent

turning point identified in this report is real, and if so,

whether the improving trend can be not merely sustained over

the coming decade, but further accelerated. Monitoring will

also illuminate which of our policies, programmes and

practices are in fact working to reduce these inequalities

and their drivers – and which are not.

When will the

next monitoring report be released?

The fifth

monitoring report in the Decades of Disparity series,

covering the 2006-09 period, should be available in 2011 or

2012.

What is the definition of mortality?

Mortality rate or death rate measures the total number

of deaths per 100 000 population. All rates reported here

have been standardised for age over the 1-74 age range.

Rates for income groups have been standardised for both age

and ethnicity. Ethnic rates are not standardised for income

as income is a mediator, not a confounder, of the ethnicity

- mortality association.

Where can I find a copy of

the report?

Tracking Disparity: Trends in ethnic and

socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, 1981–2004 will be

available on the Ministry of Health website at:

http://www.moh.govt.nz/publications

Michael King Writers Centre: Shilo Kino Awarded 2025 Shanghai Writing Residency

Michael King Writers Centre: Shilo Kino Awarded 2025 Shanghai Writing Residency Burnett Foundation Aotearoa: S.L.U.T.S Might Be The Answer To Ending Syphilis Outbreak

Burnett Foundation Aotearoa: S.L.U.T.S Might Be The Answer To Ending Syphilis Outbreak Aotearoa Covid Action: Pharmac Urged To Widen Access To Covid Vaccines

Aotearoa Covid Action: Pharmac Urged To Widen Access To Covid Vaccines Howard Davis: Dick Frizzell’s Hastings & Studio International Revisited In Wellington

Howard Davis: Dick Frizzell’s Hastings & Studio International Revisited In Wellington Heritage New Zealand: New Education Resource On Ōtūmoetai Pā Released

Heritage New Zealand: New Education Resource On Ōtūmoetai Pā Released Bowel Cancer NZ: Broken Promise, Lost Lives - Govt’s Bowel Cancer Screening Pledge 98% Undelivered

Bowel Cancer NZ: Broken Promise, Lost Lives - Govt’s Bowel Cancer Screening Pledge 98% Undelivered