"I have lived long enough. My way of life

Is fall'n into the sere, the yellow leaf,

And that which should accompany old age,

As honor, love, obedience, troops of friends,

I must not look to have, but, in their stead,

Curses, not loud but deep, mouth-honor, breath

Which the poor heart would fain deny and dare not."

- Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 3.

'Most of one's life is an entr'acte,' said Gumbril, whose present mood of hilarious depression seemed favourable to the enunciation of apophthegms.

'None of your cracker mottoes, please,' protested Mrs. Viveash. All the same, she reflected, what was she doing now but waiting for the curtain to go up again, waiting, with what unspeakable weariness of spirit, for the curtain that had rung down, ten centuries ago, on those blue eyes, that bright strawy hair and the weathered face?

'Thank God,' she said with an expiring earnestness, 'here's the second scene!'

- Aldous Huxley, Antic Hay

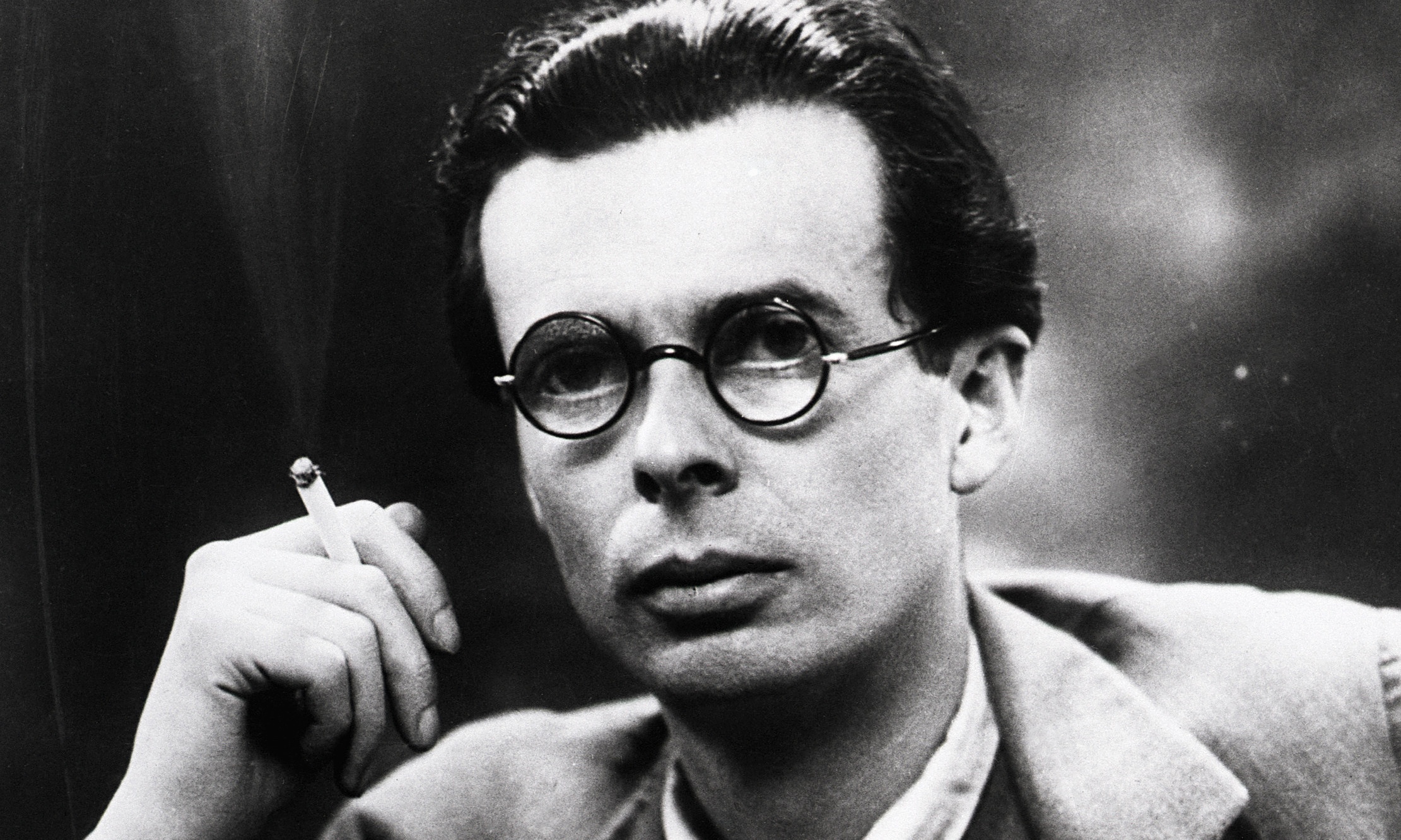

Born in 1894, Aldous Huxley was the scion of a famous intellectual family, the third son of the writer and schoolmaster Leonard Huxley, who edited the literary Cornhill Magazine, and his first wife, Julia Arnold, the niece of poet and critic Matthew Arnold and the sister of Mrs. Humphry Ward. He was the grandson of Thomas Henry Huxley, the controversial zoologist and agnostic, popularly known as 'Darwin's Bulldog.' His brother Julian and half-brother Andrew also became outstanding biologists. Julian described Aldous, whose childhood nickname was 'Ogie' (short for ogre), as someone who frequently contemplated “the strangeness of things." According to his cousin, he also had an early interest in drawing. He experienced a challenging adolescence during which his mother died of cancer, his brother Noel committed suicide after a period of clinical depression, and he contracted keratitis which inflamed his corneas. In a Paris Review interview, he admitted his sight was impaired for a several years in his late teens - “I started writing when I was seventeen, during a period when I was almost totally blind and could hardly do anything else. I typed out a novel by the touch system; I couldn’t even read it.” Although he volunteered for the British Army in January 1916, he was rejected on health grounds since he was effectively half-blind in one eye. His vision later partly recovered, but he was forced to wear thick corrective lenses for the rest of his life. He could talk about a wall-size Veronese as if he could see it in a single glance, when in fact he had to look at it a few square inches at a time. From his fluent historical prose it might easily be assumed that he read Macaulay, but not that he did so in Braille.

Huxley first visited Garsington Manor while still an undergraduate in November 1915. At a loose end after graduating from Balliol College, Oxford, with a first class honours degree in English Literature, he moped around the grounds hopelessly beguiled by Maria Nys, an extremely young and attractive bisexual Belgian refugee. He proposed to her at Garsington in 1916, but when Maria decided to join her mother in Florence in December, Huxley asked the Morells if he could continue to live there rent free in exchange for working on the farm. He lodged at Garsington from August onward, enjoying the stimulating company, writing reviews, and contributing to various periodicals. While the 'Bloomsberries' spent most of their time eating, drinking, and copulating, Huxley found himself chopping wood by day and reading at night. His urge to marry Maria was incompatible with this agretic way of life and he decided to leave in April 1917, addressing an eloquent letter to his hosts in which he claimed that his stay with them had been “the happiest time in his life.” While pretending the experience had been an inspiration, Huxley had in fact been dipping the poisonous quill with which he composed Crome Yellow in arsenic.

Huxley's venomous portrait of the inter-war period is reminiscent of Evelyn Waugh, who mined similar territory, but with even greater acerbity. Waugh briefly mentions Huxley's second novel in Brideshead Revisited (1945) - “I had just bought a rather forbidding book called Antic Hay, which I knew I must read before going to Garsington on Sunday, because everyone was bound to talk about it, and it's so banal saying you have not read the book of the moment, if you haven't.” Wyndham Lewis (whose sardonic, incisive, and mordantly satirical The Apes of God (1930) revealed him, more than Waugh, to be the century's real heir to Swift) sketched out a typical weekend gathering at Garsington in Blasting and Bombardiering (1935) -

“Forty or fifty undergraduates would come over for an all-day party, and week-end guests of Ottoline would encounter this horde of the 'academic youth' of England. I met Forster there as a fellow-guest, the 'Bloomsbury novelist.' A quiet little chap, of whom no one could be jealous, so he hit it off with the 'Bloomsburies,' and was appointed male opposite number to Virginia Woolf. Since then he has written nothing. But the less you write, in a ticklish position of that sort, the better.

I may include a photograph of myself on the lawn where they played interminable croquet, in conversation with Lord David Cecil and other undergraduates … Lady Ottoline herself in the 'post-war' shared with Miss Sitwell the distinction of being the only woman not to succumb to the short-skirt fashion: both stalked about in sweeping trains, to the astonishment of the world which had gone strip-tease. Also the majestic splendour of their personal ornaments added to the general confusion in their neighbourhood.”

Published when Huxley was only twenty-seven, Crome Yellow is quite distinct from his later novels like Brave New World (1932), albeit laced with historical allusions that seep subversively through the cracks, providing oblique glimpses of future malignancies that had yet to take root and flourish. Nothing much happens in this short novel, which is largely given over to dialogue between Priscilla and Henry Wimbush and their parasitic collection of house guests, whose conversation centers on some of the great issues of the times - heritage and ancestry, culture and civilisation, scholarship and learning, human relationships and the vagaries of love. Henry's composition of a massive history of the Crome estate provides some entertaining vignettes when he shares selections from his heavily-researched volumes with his captive audience. These tangents are often hilarious, especially those concerning an ancestor's fixation on locating the toilets atop the four towers, and establish an elegant archeological counterpoint to some otherwise inauspicious and rather tawdry goings-on.

The novel's title puns enigmatically on the pigment chrome yellow, which on one level suggests the sun that revolves in the cerulean sky and evokes a brightly pastoral and elegiac mood throughout the narrative. It is worth noting that the first recorded use of chrome yellow as a colour name in English occurred almost exactly one hundred years earlier in 1818. Previously, artists relied on orpiment, an arsenic sulfide mineral that derives its name from the Latin auripigmentum (from aurum - gold + pigmentum - pigment) because of its deep orange-yellow colour. Orpiment was traded in the Roman Empire as a fly poison and to tip arrows, and employed as a medicine in China, even though it is highly toxic. For centuries, orpiment was ground down and used in painting and for sealing wax, and because of its strikingly clear colour, it was also of interest to alchemists in search of a way to make gold. It was one of the few bright yellow pigments available to artists, but its extreme toxicity meant that its use as a pigment ended after the French chemist Louis Vauquelin discovered the new chemical element chromium in 1797 and cadmium and chromium yellows were introduced in the second decade of the nineteenth century.

Huxley may also have intended a buried allusion to conscientious objectors as cowardly, or even a reference to cromlechs (prehistoric erections of large phallic stones). Given his classical eduction, however, it may be more salient that in the Iliad Homer named Achilles' immortal talking horse Xanthos, which means yellow in Greek. He also described the Trojan War heroes Glaucus and Sarpedon as coming from the land of the Xanthos River, which usually has a yellow hue because of the soil in the alluvial base of the valley through which it flows. Xanthus is mentioned by numerous ancient Greek and Roman writers, including the Greek geographer and historian Strabo who reported that Xanthos was the largest city in Lycia, an ancient center of culture and commerce not only for the Lycians, but also during subsequent conquests by Persians, Greeks, and Romans. He noted that the original name of the Xanthus River was Sibros or Sirbis, and during the Persian invasion the river was called Sirbe, which also means yellow. Xanthos was a Greek name acquired during its Hellenization, while the Romans later called the city Xanthus (the Greek suffix -os was replaced by -us in Latin).

Xanthos was originally the chief city state of the Lycians, an indigenous people of southwestern Anatolia, and is famous for its pillar tombs, formed by placing a stone burial chamber on top of a large obelisk. Governed by a succession of kings under an Achaemenid Empire governor, the continuity of their dynastic rule was reinforced by the tradition of building these tombs during a period when Late Classical Greek ideas of art pervaded Lycian imagery. They were designed for male members of the dynasty who ruled from the sixth to the fourth century BCE, not only serving as monuments to preserve their memory, but also displaying the adoption of Greek decorative styles. The pillars were discovered by Sir Charles Fellows, many of whose drawings were used to illustrate Lord Byron’s Childe Harold, and who gained permission in 1842 to ship seventy-eight cases of Lycian sculpture and architectural fragments back to England. In 1844, he acquired an additional twenty-seven cases of statuary for the British Museum, located deep in the heart of Bloomsbury, earning him a knighthood in 1845.

This sort of deep excavation into the historical record suggests that the concept of depicting the ruins of a fading culture and civilisation was fermenting in Huxley's mind during the writing of his novel, which unfolds over a period of three weeks in July and August, shortly after the Armistice. It might also explain the absence of male heirs and Priscilla's abiding interest in the sort of faux-spiritualism professed by Theosophists like Annie Besant. Despite the late summer sunshine, it is a twilight era that is rapidly drawing to a close, as this description of another dilapidated estate, Gobley Great Park, suggests -

“A stately Georgian pile, with a facade sixteen windows wide; parterres in the foreground; huge, smooth lawns receding out of the picture right and left. Ten more years of the hard times and Gobley, with all its peers, will be deserted and decaying. Fifty years, and the countryside will know the old landmarks no more. They will have vanished as the monasteries vanished before them.”

Additional evidence for identifying the era in which the novel is set as a transitional period of moral disintegration lies in the apocalyptic sermon that the steely grey, “iron-faced”, and retrograde parson Mr. Bodiham preaches in Chapter IX, specifically dated about four years after the start of the war which has now "come to an end."

The novel's protagonist, a gravely studious twenty-three year old named Denis, is an aspiring writer desperate to attain both literary recognition and requited love among Priscilla's salon littéraire inhabited by a cluster of characters who easily slip between sombre complexity and farcical hilarity. He has recently published a “slim volume” of poetry and imagines himself a dashing man of action, whereas he is actually an introspective intellectual who, like many of Huxley's subsequent heroes, never manages either to articulate or achieve his goals. When we first meet him, he is suffering from writer's block while trying to work on a novel and admits to a nihilist lack of faith in anything, including the potency of his own art. While Denis is serious and understated, Priscilla embodies Ottoline Morrell, who assembled around her the most glittering noetic cenacle of the era, as a flamboyant hostess with bouncy red hair, enormous pearl necklaces, and an abiding interest in spiritualism and astrology. Her husband Henry, obviously modeled on Philip Morrell, is the proud historian of the house who prefers to live in the musty archives of the past.

Crome Yellow is populated with bright people making speeches that tend to quote other people's speeches. Even the few dullards, wheeled in for purposes of contrast, are weighed down with learning, like the pompous literary hack Barbecue-Smith, the author of platitudinous best-sellers peddling spiritual uplift -

“Mr. Barbecue-Smith arrived in time for tea on Saturday afternoon. He was a short and corpulent man, with a very large head and no neck. In his earlier middle age he had been distressed by this absence of neck, but was comforted by reading in Balzac’s Louis Lambert that all the world’s great men have been marked by the same peculiarity, and for a simple and obvious reason: Greatness is nothing more nor less than the harmonious functioning of the faculties of the head and heart; the shorter the neck, the more closely these two organs approach one another.”

A self-help writer of prodigious output who claims to compose 1,500 words per hour by channeling his subconscious, Barbecue-Smith would appear to be a fraudulent oaf, but Huxley could not resist making him an oaf who has read Balzac. One of his speeches goes on almost uninterrupted for two and a half pages, bringing in a large part of the history of civilization since the Renaissance as he forecasts a more rationally ordered future - “In the upbringing of the Herd, humanity’s almost boundless suggestibility will be scientifically exploited.”

In pursuit of a plausible idea, characters often come to a standstill and simply spout, like the fountains in the garden, when they would do better to pursue their passions as devoutly as Priscilla chases after hers - namely, other women's husbands, astrology, and the occult. For Priscilla, weirdly attired and tireless in her extravagance, they are all objects of desire, retreating tantalizingly down the corridors of Crome and floating out through the mullioned windows. The opinionated, pipe-smoking, and slightly diabolical Scogan (a loose amalgam of Bertrand Russell and Norman Douglas) is a pessimistic philosopher who drafts the outlines of a dystopian future, allowing for the fissures in the novel through which the seeds of Brave New World will germinate and sprout. Gombauld, a rakish and predatory portrait painter with “flashing teeth” and “luminous large dark eyes” in search of a more transcendent form of art than abstraction, is based on Mark Gertler. Another dodgy characters is the lecherous lothario Callamy, who has been likened to the politician H.H. Asquith, "a ci-devant Prime Minister feebly toddling across the lawn after any pretty girl.” Wyndham Lewis, who seems to have known everyone who was anyone during this period, mentions meeting the later Lord Oxford, who became Prime Minister in 1914, on several occasions at Ottoline's “crowded receptions … of fashion and 'intellect' mixed in equal measure” at her London home in Bedford Square. While Asquith “plunged England into an unprecedentedly destructive and unsuccessful war,” Lewis was “thinking of a little tube of paint, of Emerald Oxide of Chromium, with which I had just worked wonders.”

There are three single women in attendance at Crome, Mary, Jenny, and Anne, all of whom are the objects of various attempts at seduction that manage to go spectacularly awry. Mary is based on the disturbed painter and decorative artist Dora Carrington, who had a lengthy relationship with the homosexual historian Lytton Strachey, whom she first met at Garsington in 1916. Distinguished by her cropped pageboy hair style (before it was fashionable) and androgynous appearance, Huxley gives her the surname 'Bracegirdle' due to her confused sexuality. He describes how they slept chastely together on the roof of the manor house, as she lusts after the charming Ivor Lombard, who seems to be a combination of Noel Coward and Ivor Novello, thus dooming her project to unrequited failure. Anne is the bewitching, charming, and condescending cynosure, seemingly inspired in equal parts by Virginia Woolf and Mary Hutchinson. Volumes have already been written about Woolf, but of much greater interest to the Huxleys was the more enigmatic figure of Hutchinson, who was both Strachey's cousin and Duncan Grant's first cousin once removed.

Mary Hutchinson was a central figure in the Bloomsbury universe. Throughout her life, she was the inspiration and model for many artists, including Henry Tonks’ comic, Boucheresque illustrations of The Lovers of Orelay, a somewhat scandalous episode in George Moore’s autobiography Memoirs of My Dead Life, first published in 1906. In 1916 Virginia Woolf's bisexual sister Vanessa Bell painted an particularly unflattering portrait of Hutchinson, entitled The Tub, which she described as "perfectly hideous... and yet quite recognizable." Hutchinson was also the model for her Nude with Poppies, a reclining semi-abstract figure study overshadowed by giant poppies which Vanessa painted for the bedroom of the Hutchinson home at River House in Hammersmith, “either as a supremely open-minded gesture or a sardonic jab at the lady in question,” according to Ian Dejardin, co-curator of the first major solo exhibition devoted to Vanessa Bell's work at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2017. In a letter to her husband, St. John 'Jack' Hutchinson, quoted by Richard Shone in his Tate Gallery exhibition catalogue The Art of Bloomsbury, Vanessa wrote - “Please tell Mary I’ve been painting her bed - I hope she won’t be horrified to hear there’s a nude figure of the most romantic description with poppies and waves - asleep - and bouquets of flowers and white satin ribbon - I don’t think it’s at all what she wanted … “

Duncan Grant draw a more

flattering sketch of Hutchinson in 1917 and the Bells

introduced her to Henri Matisse, who drew her portrait twice

in 1936, one of which sold at Sotheby’s in 2018 for

£3,130,000. Mary's beauty was so enduring that in the early

1930s Russian artist Boris Anrep used her as a model for

Erato, the muse of lyric poetry, in his The Awakening of

the Muses mosaic, designed for the entrance hall of

London's National Gallery.

Like moths fluttering around an incandescent flame, writers and painters were drawn to River House, where the Hutcninson's often entertained the Huxleys, the Bells, the Eliots, the Woolfs, Maynard Keynes, and Mark Gertler among many others. Mary and Virginia Woolf were intimate friends and, although it is unclear to what extent their relationship was amorous, Hermione Lee claimed in her biography of Woolf that Hutchinson was the "main inspiration for the febrile socialite Jinny in The Waves. She may have lacked the creative drive of many of her contemporaries. But compensated for it with a wide variety of sexual partners, including Vanessa's husband Clive, with whom she maintained an indiscreet affair from 1914 until 1927, Vita Sackville-West, Henry Matisse's son-in-law Georges Duthuit, and possibly T.S. Eliot, with whom she maintained a close correspondence from 1916 until the last months of his life. According to Lewis, shortly after the War ended, Eliot “challenged Mr. St. John Hutchinson to a duel, upon the sands at Calais. But the later gentleman, now so eminent a K.C., replied that he was 'too afraid.' So he got the best of that encounter, as one would expect when a K.C. clashes with a poet.” Mary's letters reveal that she also maintained an overlapping, but more discrete relationship with Huxley and his wife Maria from 1922 to 1930, although this was kept secret from both Jack and the est of the Bloomsbury Group.

Which returns us somewhat circuitously to another classical allusion in Crome Yellow. Of the three available young women staying at this thinly-disguised and decaying version of Garsington, Denis is particularly enamoured by Anne, who is portrayed as the gorgeous yet unattainably glamorous, man-baiting niece of Henry and Priscilla. Their home is part of the ancestral estate of the Lapiths, a Homeric name employed in a lisping Swiftian pun that is made explicit when we learn that the family's founder had an "obsession with the proper placing of his privies." This delicate reference to micturation not only extracts the piss from the louche assembly of artists, intellectuals, and dilettantes staying at Crome, but also connotes the legendary people of Greek mythology whose home was in Thessaly, on the mountain slopes of Pelion and in the sexualised valley of Peneus below.

Adorning its colonnade on the south side of the Parthenon's Doric frieze, the famous Centauromachy depicts the Lapiths fight against the Centaurs, who attempt to abduct the bride from the wedding feast of King Pirithous. The Lapith girl Caeneus was a particular favorite of Poseidon, who changed her into a man at her request and made her an invulnerable warrior, indistinguishable from men. As Greek myth became progressively mediated by philosophy, the battle between Lapiths and Centaurs adopted aspects of the interior struggle between civilized and wild behaviour, made concrete in the Lapiths' understanding of the right usage of god-given wine, which must be tempered with water and not drunk to excess. The Greek sculptors of the school of Pheidias conceived of the battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs as a struggle between mankind and mischievous monsters, symbolic of the conflict between the civilized Greeks and “barbarians.” In addition to being depicted on the Parthenon's sculptured metopes and Zeus' temple at Olympia, battles between Lapiths and Centaurs were a familiar symposium theme of Attic vase painters. During the Renaissance, such skirmishes became a favourite motif for painters, providing them with an excuse to display close-packed bodies in violent conflict. Michelangelo executed a marble bas-relief of the subject in Florence about 1492, while Piero di Cosimo's early 16th century panel Battle of Centaurs and Lapiths is now on display at London's National Gallery. The subject is taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses and shows drunken centaurs disrupting the wedding feast, one of them seizing the bride by her hair. Among many grotesque and lewd incidents is the lyrical episode of the centaur Hylonome kissing her lover Cyllarus as he dies from a javelin wound.

Huxley's knowledge of ancient Greek history may have been impeccable, but both the reader and Denis soon learn that the plot of his projected novel, which is predicated on his own misguided understanding of himself, is entirely predictable. Denis is sufficiently ashamed of his sexual aspirations to blush when broaching them - not for nothing, it seems, is his name spelled like penis. His lack of originality (which he conceives as central to artistic creation) is revealed when he acknowledges that “things somehow seem more real and vivid when one can apply somebody else's ready-made phrase about them.” Denis blames his inadequacy on his public school and university education, complaining that -

“One entered the world … having ready-made ideas about everything. One had a philosophy and tried to make life fit into it. One should have lived first and then made one's philosophy to fit life … Life, facts, things were horribly complicated; ideas, even the most difficult of them, deceptively simple. In the world of ideas everything was clear; in life all was obscure, embroiled.”

Even if we ignore the false opposition between life and ideas and accept the validity of his excuse for his frustration, Denis' timidity prevents him from being either willing or able to transcend the stultifying effects of his classical education. Although he periodically spouts snatches of verse, this does not prevent him from potentially being a sympathetic character and his shy yearnings provide an inviting source of identification. At two crucial moments, however, he is shown to be little more than a shallow shell, a self-described lover of "words," not “things and ideas and people.” Denis' inability to act, even when proffered an instructive example, is first demonstrated in an extended set-piece in Chapter XIX. When Henry recounts the story of his not-so-aristocratic grandfather who won the hand of one of the Lapiths, with a mixture of curiosity and blackmail, Denis proves himself entirely incapable of taking the hint. After another unsuccessful attempt to “write something about about nothing in particular” in Chapter XXIV (which is in many ways the climax of the novel), Denis discovers Jenny's red notebook. It contains a caricature of himself reading a book (upside down) entitled “Fable of The Wallflower and the Sour Grape” and more “unobtrusive scribbling” that reveals he is by no means "his own severest critic.” Although he never wonders why Jenny's notebook has been left lying around so casually, he finally recognises the foolishness of his delusions and his hurt pride is completely understandable -

“There are times when he comes into contact with other individuals, when he is forced to take cognisance of the existence of other universes besides himself ... One is apt … to be so spellbound by the spectacle of one's own personality that one forgets that the spectacle presents itself to other people as well as to oneself."

“I am amazed how ignorant I am of other people's mentality in general and, above all and in particular, of their opinions about myself. Our minds are sealed books only occasionally opened to the outside world.”

None of this is patently false, but Denis fails to show any curiosity about Jenny, who is revealed as the most interesting and reflective character among the other self-absorbed house guests. His lack of self-awareness means he can never achieve anything, sexual failure and frustrated desire being a leading theme throughout this “comic novel of ideas,” which paradoxically fails to engage fully with either the comedy or the ideas. There are several lightweight and amusing passages, and several moments provide launching points for further reflection, but by soliciting the reader's complicit superiority to its main character, the novel merely encourages our own complacency. Fortunately, however, the simplicity of the plot, which pivots around Denis’ efforts to gain admiration from both the literary community and Anne, is effectively counterbalanced by the intricate dance of the supporting characters, the history of the estate, and the romantic setting of the sexualised landscape -

“And within a radius of twenty miles there were always Norman churches and Tudor mansions to be seen in the course of an afternoon's excursions. Somehow they never did get seen, but all the same it was nice to feel … that one fine morning one really might get up at six … Curves, curves: he repeated the word slowly, trying as he did so to find some term in which to give expression to his appreciation … What was the word to describe those little valleys? They were as fine as the lines of the human body, they were informed with the subtlety of art … Those little valleys had the lines of a cup moulded round a woman's breast; they seemed the dinted imprints of some huge divine body that has rested on these hills. Cumbrous locutions these; but through them he seemed to be getting nearer to what he wanted. Dinted, dimpled, wimpled - his mind wandered down echoing corridors of assonance and alliteration ever further and further from the point. He was enamoured with the beauty of words.”

This combination of uncomplicated narrative and richly textured vocabulary allows for some densely descriptive language, exemplifying Denis’ constantly deferred desire to select exactly the right word with which to identify and classify everything. This impossible longing is eloquently illustrated in Chapter I - “Some day he would compile a dictionary for the use of novelists. Galbe, gonflé, goulu: parfum, peau, pervers, potelé, pudeur, virtue, volupté.” Similarly, the passage in which he recalls his early love for the word ‘carminative’ (which he imagines refers to the warm and golden sensation of liquid cinnamon trickling down your throat) and his later discovery of the actual meaning of the word (a drug to relieve flatulence), amplifies Huxley's poignantly comical account of a callow youth'’s linguistic inadequacy. It also provides Denis with at least one invaluable insight -

“That's the test of the literary mind,” said Denis; “the feeling of magic, the sense that words have power. The technical, verbal part of literature is simply a development of magic. Words are man's first and most grandiose invention. With language, he created a whole new universe ... Wth fitted, harmonious words the magicians summoned rabbits out of empty hats and spirits from the elements. Their descendants, the literary men, still go on with the process, morticing their verbal formulas together and, before the power of the finished spell, trembling with delight and awe.”

Although the novel's short declarative sentences and abrupt chapter divisions adhere unpretentiously to the modernist concept of ‘less is more,' such contemplative analyses of the power of words and the resonance of their etymology leavens its intellectual heft. Crome Yellow is crammed full of intimate suggestion, anxious suspicion, and implied innuendo that only occasionally burst out into the brilliant cadmium light of day, such as the sinister and saturnine sketches of Callamy and Lord Moleyn as malevolent and minatory pederasts -

“Beside him, short and thick-set, stood Mr. Callamy, the venerable conservative statesman, with a face like a Roman bust, and short white hair. Young girls didn't much like going for motor drives alone with Mr. Callamy; and of old Lord Moleyn one wondered why he wasn't living in gilded exile on the island of Capri among the other distinguished person who, for one reason or another, find it impossible to live in England.”

The Vintage Classics edition includes a preface by Malcolm Bradbury, who carefully claims it is a “comic novel of ideas” that can “go on being read with complete delight and pleasure.” He admits that the book contains "satirical tales cunningly planted in the story," including the Swiftian "narrative of Sir Hercules Occam, the perfectly-formed dwarf who builds his perfect dwarf estate until all is destroyed by a full-sized heir," but he is correct to claim the book is not a fully-fledged satire. Scott Fitzgerald remarked that Crome Yellow is “too ironic to be called satire and too scornful to be called irony” and it lacks the kind of "disgust, rancour and pessimism" that Orwell found in Gulliver's Travels. Although some of the novel's slower sections dealing with the history of the estate could have been pruned, it is easy to see why the novel's frothy, amusing, and unpretentious style immediately established Huxley's literary status, as he later claimed in his Foreward to Point Counter Point (1928). His lighthearted portrayal of a palpably privileged and aristocratic milieu, combined with his philosophical insights and erudite vocabulary, remains both instructive and entertaining.

In light of Brave New World, it is also easy to appreciate the danger inherent in some of the more absurd political arguments debated in Crome Yellow. Readers interested in totalitarian repression will appreciate the subtle doubts raised about Scogan's vision of a more orderly "impersonal generation" of the future that will"take the place of Nature's hideous system. In vast state incubators, rows upon rows of gravid bottles will supply the world with the population it requires. The family system will disappear; society, sapped at its very base, will have to find new foundations; and Eros, beautifully and irresponsibly free, will flit like a gay butterfly from flower to flower through a sunlit world." Huxley's mature works like Ape & Essence, The Devils of Loudon, Brave New World Revisited, and Island provide more full-bodied depictions of dystopia and utopia.

After traveling around Europe for a while, Huxley returned to London for the publication of Crome Yellow in 1921. Some members of the Bloomsbury Group felt betrayed by the way in which he had caricatured them, ridiculing intimate details of their everyday lives with mockery and their convoluted conversations with contempt. Huxley's Selected Letters include some revealing correspondence with Ottoline. His letters to her are those of an apprentice to a grande dame, who initially welcomed him with open arms until the publication of Crome Yellow, which seemed a betrayal of her hospitality. Ottoline felt he had taken unfair advantage of her generosity and wrote him an angry letter about his disloyalty. She received a long and pained reply from Huxley, who pretended that the only caricature contained in the book was of himself and that the other characters were just “puppets.” "Your letter bewildered me," Huxley protested, "For, after all, the characters are nothing but marionettes with voices, designed to express ideas and the parody of ideas. A caricature of myself in extreme youth is the only approach to a real person," adding that “we are all straight lines destined to meet only at infinity. Real understanding is an impossibility.” He conceded, however, that it may have been a mistake "to use some of Garsington's architectural details." Although an apparently irreparable rupture had separated them forever, the book's publication did not prevent the Huxleys from continuing to socialise with the Woolfs, the Bells, and the Hutchinsons.

A re-reading of Crome Yellow as a relatively restrained portrait of an idle group of dilettantes playing country-house games while the fog of war still lingered suggests that Ottoline had few grounds for complaint, especially considering that Garsington was in reality such an incestuous hothouse of sexual shenanigans. In his 2002 biography Aldous Huxley: an English Intellectual, Nicholas Murray points out that Huxley apologized when Ottoline bridled, but the sad fact is that he betrayed her all over again when he sent Lilian Aldwinkle heavily emoting through the pages of Those Barren Leaves (1925). As the chatelaine of the Cybo Malaspina, a Garsington relocated to Italy, Lilian is a menopausal man-eater aching to blend her loins with just one more genius. If all the other characters had been given the free rein he gave Lilian, Those Barren Leaves would never have ceased to be required reading, but the book’s leading man is a typical Huxley hero. Effortlessly knowledgeable and seductive, he retreats to a hilltop to make long speeches about his quest for a higher form of being. His soliloquies leave you longing for Lilian, who has Ottoline’s lust for life as well as her quenchless thirst for a fad. Though Ottoline was untiring in her zeal as a people-hunter, as a dinner-table hostess she was a genuine talent spotter, and Huxley’s was hard to miss.

Huxley may have deeply wounded her, but he could at least console himself with the knowledge that he left Garsington not only with sufficient material for his first work of fiction, but also having met both his future wife and mistress. Although Aldous and Maria were married in July, 1919, they continued to indulge in a complicated ménage-a-trois with Mary Hutchinson throughout the 1920s. In her unpublished memoirs she admitted, “Of the two Huxleys … Maria was the one I loved … She always seemed to be sweetly scented, oiled, and voluptuous.” Maria and Mary were not the only objects of Huxley's amorous interest during this period, however. Although she does not put in a personal appearance until his next novels, the characters of Myra Viveash in Antic Hay and Lucy Tantamount in Point Counter Point (1928) are based upon the notorious society heiress Nancy Cunard, a minor poet who was published alongside Huxley in the Sitwell’s anthology Wheels and moved in the same artistic circles.

In Blasting and Bombardiering, Wyndham Lewis describes how he first met Cunard “when she was a debutante before the War, in the house of the countess of Drogheda off Belgrave Square. She was very American and attractive after the manner of the new World, rather than the Old. She is still all this, and has been on the Aragon Front helping the Catalans to repel the attack of the 'Rebels,' whether successfully or not it is impossible to say at present.” Unlike such modernist writers of the period as Eliot, Lewis, and Pound, who were initially supportive of Franco, Mussolini, and even Hitler, Cunard accurately predicted that the "events in Spain were a prelude to another world war" and devoted her life to fighting racism and fascism. She helped deliver supplies and organize the relief effort in Spain, but poor health caused by exhaustion and the conditions in the camps forced her to return to Paris, where she stood on the streets collecting funds for the refugees.

According to Anne Chisholm's

biography, in 1920 Cunard recovered from a near-fatal

hysterectomy while living in Paris which enabled her to lead

a promiscuous sex life without running the inconvenient risk

of pregnancy. Her portrait was painted by dozens of

fashionable artists, including Wyndham Lewis, Ambrose

McEvoy, and Chilean painter Álvero Guevara, and she was the

subject of photographs by Man Ray, Curtis Moffatt, and Cecil

Beaton. When Ernest Hemingway published The Sun Also

Rises in 1926, many readers complained that the book was

indebted to Armenian novelist Michael Arlen’s The Green

Hat (1924), since both Hemingway’s heroine Brett

Ashley and Arlen’s Iris Storm were modelled on Cunard. Not

only does she make an appearance in Pound’s Cantos,

but she was also the inspiration for the redacted character

of Fresca in early drafts of Eliot's The Waste Land.

Contemporary gossip also included the latter among her many

lovers, although his legendary discretion left little

evidence to confirm this suspicion. In later years, the

wafer-thin Cunard suffered from mental illness and poor

physical health, worsened by alcoholism, poverty, and

self-destructive behaviour. She was committed to a mental

hospital after a fight with London police and her health

declined even further after her release. She weighed less

than sixty pounds when she was found wandering around the

streets of Paris in 1965 and brought to the Hôpital Cochin,

where she died two days later.

Just as Huxley became infatuated with Cunard in 1922, the protagonist of Antic Hay, Theodore Gumbril, is obsessed with the constantly “expiring” Myra, who has never recovered form the loss of her lover Tony Lamb and claims she “can tell you all about heroin.” Cunard was similarly desolated by the death of her lover Peter Broughton-Adderley in WWI, which left her chronically lonely and incapable of love. Although she was subsequently attracted to a succession of strong, masterful men such as Lewis, Pound, Guevara, and the Surrealist writer Louis Aragon, she remained relatively indifferent to the sensitive and cerebral Huxley. Nonetheless, despite his aversion to crowds, he doggedly followed her entourage on nocturnal jaunts to the Eiffel Tower restaurant and the Café Royal. In his autobiography, Alex Waugh identified the jazz nightclub that Gumbril and Myra visit as The Cave of Harmony cabaret in Charlotte Street, which was run by Elsa Lanchester and Harold Scott, who put on a performance of one of Huxley plays. Cunard eventually submitted to Huxley’s advances out of “pity” and “affection,” but cruelly likened the experience to “being crawled over by slugs” and dumped him a few days later. Despite this rebuff, Huxley remained ensorcelled by his siren whose spell was only broken when Maria threatened to divorce him if he did not leave with her for Italy the following day. Huxley acquiesced and wrote Antic Hay in a cathartic burst from June to July of 1923 in Forte dei Marmi in northern Tuscany.

In light of his demeaning obsession with Cunard, Huxley’s depiction of Myra is surprisingly sympathetic and psychologically acute. Myra is goaded into an endless succession of empty affairs by a toxic combination of grief and boredom. More than any of his other characters, she embodies the distinctive accidie that affected many of Huxley’s peers in the post-war period -

“Life, Mrs. Viveash thought, looked a little dim this morning, in spite of the fine weather … [she] had no engagements. All the world was before her, she was absolutely free, all day long … But today … she hated her liberty. To come out like this at one o'clock in the afternoon - it was absurd, it was appalling. The prospect of immeasurable boredom opened before her. Steppes after steppes of ennui, horizon beyond horizon, for ever the same. She looked again to the right and again to the left. Finally she decided to go to the left.”

In an essay collected in On the Margin (1923), Huxley traced the cultural history of this incapacitating apathy back to what was known in the Middle Ages as the dæmon meridianus or 'noonday demon' that afflicted the hermits of the Thebaid with such a crippling sense of futility it ultimately undermined their faith. Chaucer in The Parson’s Tale characterised “the synne of worldly sorrow” as “one of the eight principle vices” that lead to sluggishness, sloth, and impiety. During the Renaissance the disease was considered a medical condition and attributed to a malfunctioning spleen, caused by an imbalance of Jonsonian 'humours.' It reached its apotheosis under the Romantics, for whom it was an “essentially lyrical emotion, fruitful in the inspiration of much of the most characteristic modern literature.” Huxley argued that the features of its contemporary incarnation are ‘”sorrow,” “despair,” and a “Baudelairean sense of ennui,” and diagnosed many causes, including the failure of the French Revolution and the “defilement” of the Industrial Revolution. The chief culprit, however, was what he called the “appalling catastrophe of the War of 1914” -

“Other epochs have witnessed disasters, have had to suffer disillusionment; but in no century have the disillusionments followed on one another’s heels with such unintermitted rapidity as in the twentieth for the good reason that in no century has change been so rapid and profound ... With us [accidie] is not a sin or a disease of the hypochondries; it is a state of mind which fate has forced upon us.”

The solution to such an

enduring malaise, as Huxely later envisaged it, lay in

finding a means of radically altering this pre-conditioned

“state of mind,” of effectively changing our

consciousness.

Having

escaped Cunard's clutches, the Huxleys lived in Montici,

near Florence, from 1923 to 1925, but this did not prevent

them from continuing to solicit Mary Hutchinson's company.

"Why don't you come to us here, Mary?" Huxley wrote from

Italy in 1926, extending the invitation on behalf of Maria

and himself. "We could renew all the pleasures - invent new

ones perhaps, if there are any that we have still left

untried." In November, he thanked her for her postcard of

“the androgyne" and two days later, another card arrived,

with Bronzino's Venus on one side "and you emerging

from the written words as deliciously naked and desirable,

on the other." Time and distance eventually cooled the

ardour of their triangular relationship into a more remote

friendship, as the deracinated couple toured Europe wth

Maria at the helm of their Bugatti. Murray reveals how the

Huxleys life together during the twenties and early thirties

was punctuated by snobbish, flippant, and prejudiced

comments such as "How tremendously European one feels when

one has seen these devils in their native muck ... In fifty

years time, it seems to me, Europe can't fail to be wiped

out by these monsters" (Aldous on Tunisian arabs) and "The

coast is so over built with awful people … that I don't

know how long we really shall be safe" (Maria on the South

of France). Murray's main advance over Sybille Bedford's

1973 biography is that she, being a close friend of the

Huxleys, had drawn a veil over many aspects of their private

life. According to Bedford, Huxley "seriously pursued only

two women in his life - Maria and Nancy," but the great love

of both Maria and Aldous' life was actually Hutchinson, whom

Bedford scarcely mentions. Murray claims Maria was

apparently the one who set up these liaisons, because (in

her words) "You can't leave it to Aldous, he'd make a

muddle." There were Fascists all around their various

Italian villas. Though Huxley initially saw them as not much

worse than a bad comic opera whose chorus was prone to

fisticuffs, he finally concluded, long before the Nazis

established their full grip on Germany, that a totalitarian

solution to the anomalies of mass society was worse than the

problem. Commendably, he also grasped the horrors of the

Soviet regime straightaway. He was not the only one who

thought that industrial society was turning out too many

idiots, and went on record proclaiming that one of the

greatest dangers the idiots posed was that they might elect

dictators. Not liking dictators qualified him as a

progressive in a period when George Bernard Shaw saluted

Hitler as an exemplar of creative energy and H. G. Wells

nose-dived to the foot of Stalin’s throne. While in no

way an excuse, Huxley's confused approval of eugenics as

well as his casual and reprehensible racism were common

features of this period entre-deux-guerres. He

endorsed W.H. Sheldon's inaccurate belief that the American

IQ had declined during the early twentieth century and

shared Maria's dislike of "awful people,” observing in

Brave New World Revisited - "In this second half

of the twentieth century, we do nothing systematic about our

breeding; but in our random and unregulated way we are not

only overpopulating the planet, we are also, it would seem,

making sure that the greater numbers shall be of

biologically poorer quality." That Huxley should regard

other people as the problem (“99.5% stupid,” he used to

say) is an indictment of the superior attitude adopted by

English intellectuals of the era. His distressing approval

of “intelligent and active oligarchies” in a 1927

article for Harper’s called “The Outlook for

American Culture” sprung directly from his lack of

sympathy for the 99.5%. No doubt he suppoorted eugenics for

the same reason. Murray remarked of his anti-Semitism, "The

usual explanation is that this was an unthinking feature of

the English upper middle class milieu in which Huxley grew

up. But he was not supposed to be unthinking … ” Like

Pound and Eliot, however, Huxley's lasting reputation should

not depend upon his prejudices, but rather his prescient

predictions about many of the key issues of the future.

Brave New World Revisited was published in 1958, four

years before his death, and no less than seven of the

chapters refer to propaganda, brainwashing, hypnosis, and

mind control. Huxley took Ron Hubbard's fraudulent theories

of Scientology seriously enough to develop a prognostic

apprehension about the sedative effects of mass

psycho-medication on the general public. As early as 1932 he

wrote, "[force] will be out of date the moment our rulers

are educated enough to apply the results of psychology to

their business of governing." We need only look at the

effects of Twitter and Facebook on the current political

situation, the dangers presented by global warming and

overpopulation, and the opioid epidemic to realise that his

predictions regarding political manipulation by the media,

his fear of ecological disaster, and his warnings about the

pharmaceutical industry have all proved alarmingly

prophetic. In 1937, the Huxleys eventually settled in Los

Angeles, where Aldous hung out with Christopher Isherwood

and found work as a Hollywood screenwriter, collaborating on

adaptations of classic novels such as Pride and

Prejudice and Jane Eyre. In 1945, Walt Disney

paid him $7,500 to write a treatment based on Alice’s

Adventures In Wonderland, which would have incorporated

elements of Lewis Carroll's life, but decided not to proceed

because his screenplay was “too literary.” Huxley's

reasons for relocating to California included not needing to

lower his exalted standards of smart company as European

refugees flocked in and LA soon became one of the

intellectual centers of the modern world. Thomas Mann had

been on the Normandie with the Huxleys on the trip over

(characteristically, the modern Goethe had travelled first

class, but uncharacteristically he condescended to visit

them in steerage), and now he was sharing the same cerulean

sunlight. America didn’t isolate Huxley, but it did

insulate him. Safely domiciled in a part of the world that

suffered least from deprivation and political instability,

Huxley took his surroundings for granted as a set of

conditions from which mankind could aspire to higher things,

instead of as the higher thing that the rest of the world

could only aspire to. Had he been less comfortably

cushioned, the war and its aftermath might have made more

impact on his thought. Karl Popper, exiled to New Zealand

during the war, was forced by the memory of his experience

in Europe to reach a minimum definition of democracy. It was

the system in which the government could be replaced at the

people’s whim, so that no oligarchy, intelligent or

otherwise, could perpetuate itself in power. The implication

was that the 99.5% did not need to be instructed; all they

needed was to have a vote. After living in California for

fourteen years, Huxley applied for citizenship, but his

lifelong belief in pacifism prevented him from saying he

would defend the US in wartime. He realised his application

would probably be denied because his refusal was based on

philosophical rather than religious reasons, so he withdrew

it before the government had a chance to turn him down.

Maria died of cancer in 1955 and the following year he

married Laura Archera, an author, violinist, and

psychotherapist. In his later years, Huxley frequently wrote

about mysticism in general (The Doors of Perception,

Heaven and Hell, and Moksha: Writings on

Psychedelics and the Visionary Experience 1931-63), and

Hindu and Buddhist philosophy in particular (The

Perennial Philosophy). He was an early explorer of

altered states of consciousness in the 1950s and remained a

lifelong proponent of the potential benefits of psychedelic

substances such a mescaline, magic mushrooms, and

LSD. Huxley's final novel, Island (1962), provides

a fascinating parable in this respect. It tells the story of

an Englishman, William Asquith 'Will' Farnaby, who

deliberately wrecks his boat on the Polynesian shores of

Pala, thus forcing an entry into a 'forbidden' kingdom

similar to Tibet. He is woken by a myna bird screaming

"attention” and taken to Dr. Robert MacPhail for medical

treatment, where he recognises a young man named Murugan

Mailendra from a recent meeting with the military dictator

of a neighbouring country that covets Pala's oil reserves.

Murugan reveals to Farnaby that he will be soon assuming

control over Pala as its new Raja. Farnaby establishes a

strong bond with McPhail's daughter-in-law Susila, a

hypnotherapist who directs him to re-explore his own

troubled past and guides him through painful memories of his

childhood and his wife's death on the night he confessed to

cheating on her. The novel concludes with Farnaby ingesting

the visionary moksha mushroom, a fictional entheogen

taken ceremonially in rites of passage for mystical and

cosmological insight, described as "yellow" and not "those

lovely red toadstools" (i.e. the toxic amanita muscaria).

Although this description of moksha suggests the

psychoactive mycelium psilocybin, the recommended dosage of

400 mg is within the prescribed range for mescaline.

Farnaby's ensuing hallucinations are vividly philosophical

and unspeakably vibrant. He feels a loss of self in the

oneness of everything and "knowledgless understanding,”

but can only watch in horror as a preying mantis sexually

cannibalises her partner until Susila encourages him to

relax and let the mushroom medication help him realise the

inherent natural beauty of all creation and destruction. As

dawn approaches, gunfire breaks out from a passing caravan

of military vehicles and they hear Murugan's voice through a

loudspeaker announcing the formation of the new United

Kingdom of Rendang, and instructing residents to remain calm

and to welcome the invading forces. The caravan stops to

fire a brief fusillade at MacPhail's house, then moves on as

the myna bird screams out its imperative "attention" one

last time. Many of the ideas used to describe Pala as a

utopia also appear in the last chapter of Brave New World

Revisited, which proposed actions that could be taken to

prevent democracies from turning into totalitarian states

like those described in Brave New World. Themes such

as population control, ecology, modernism, democracy,

mysticism, entheogens, and somatypes that were employed to

depict negative aspects of repression and indoctrination in

Brave New World are flipped into positive forces of

liberation and enlightenment in Brave New World

Revisited and Island. Huxley's vision has proved

remarkably prophetic and his influence on the counterculture

of the 1960s was profound. His likeness appeared on the

cover of Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Jim

Morrison and Ray Manzarek admitted taking their band's name

from his book - “there's the inside and the outside, and

in between are The Doors.” Not only have the therapeutic

effects of hallucinogens for a variety of medical conditions

ranging from severe depression, through PTSD, to

schizophrenia are finally being acknowledged, but both West

African ibogaine and Amazonian ayahausca have also been

found highly effective in treating addiction. The late

ethnobotanist and author Terence McKenna even went so far as

to tell a German audience in 1991 that virtual reality could

offer a new kind of communication like telepathy, reuniting

us with the kind of tribal community that we left behind

long ago. Marshall McLuhan's concept of an interconnected

global village remains full of potential, when it is not

abused for nefarious purposes of indoctrination and

manipulation. A heavy cigarette and pipe smoker his entire

life, Huxley succumbed to advanced laryngeal cancer at the

age of sixty-nine. On his deathbed and no longer able to

speak, according to Laura's account in This Timeless

Moment, he made a written request for “LSD, 100 µg,

intramuscular." In an article for New York magazine

titled 'The Eclipsed Celebrity Death Club,' Christopher

Bonanos commented - “The championship trophy for

badly timed death ... goes to a pair of British writers.

Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World, died

the same day as C.S. Lewis, who wrote the Chronicles of

Narnia series. Unfortunately for both of their

legacies, that day was November 22, 1963, just as John

Kennedy’s motorcade passed the Texas School Book

Depository. Huxley, at least, made it interesting: at his

request, his wife shot him up with LSD a couple of hours

before the end, and he tripped his way out of this

world.”

Michael King Writers Centre: Shilo Kino Awarded 2025 Shanghai Writing Residency

Michael King Writers Centre: Shilo Kino Awarded 2025 Shanghai Writing Residency Burnett Foundation Aotearoa: S.L.U.T.S Might Be The Answer To Ending Syphilis Outbreak

Burnett Foundation Aotearoa: S.L.U.T.S Might Be The Answer To Ending Syphilis Outbreak Aotearoa Covid Action: Pharmac Urged To Widen Access To Covid Vaccines

Aotearoa Covid Action: Pharmac Urged To Widen Access To Covid Vaccines Howard Davis: Dick Frizzell’s Hastings & Studio International Revisited In Wellington

Howard Davis: Dick Frizzell’s Hastings & Studio International Revisited In Wellington Heritage New Zealand: New Education Resource On Ōtūmoetai Pā Released

Heritage New Zealand: New Education Resource On Ōtūmoetai Pā Released Bowel Cancer NZ: Broken Promise, Lost Lives - Govt’s Bowel Cancer Screening Pledge 98% Undelivered

Bowel Cancer NZ: Broken Promise, Lost Lives - Govt’s Bowel Cancer Screening Pledge 98% Undelivered