From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

- A.E. Houseman, A Shropshire Lad XL

It is a sad week for cinephiles in which both Bernardo Bertolucci and Nicolas Roeg find themselves permanently double-parked in the great Drive-In Movie Theatre in the Sky within three days of each other. Conventional wisdom suggests such unfortunate events usually come in packs of three, so the smart money is probably on Roman Polanski popping off next ...

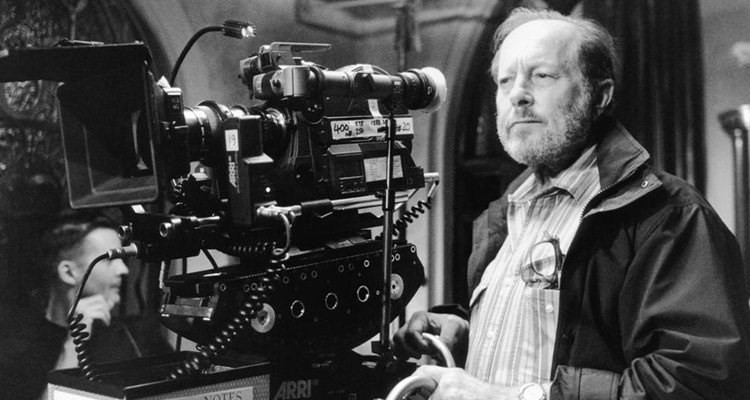

One of the most adventurous and gifted film directors of all time, with at least five movie masterpieces under his belt, Roeg died last weekend at the age of ninety. Among the many admirers who took their cue from his superb cinematography, complex editing, and fractured narratives are such celebrated directors as Danny Boyle, Todd Haynes, Steven Soderbergh, Wong Kar-Wai, and Charlie Kaufman. Christopher Nolan has admitted that Memento would have been "pretty unthinkable" without Roeg, and acknowledged borrowing the explosive ending of Insignificance when making Inception. It is amazing that Roeg managed to achieve so much and survive as long as he did, since he was a big bottle man who was partnered for many years with his muse, the much younger screen siren Theresa Russell, enough to wear out the energy of a man half his age.

At the recent NZSO performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, a friend of mine recently mentioned how hard it was for him to hear the third movement without being reminded of Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange and the formative influence it had on his misspent youth. For me, the movie was Roeg's Performance, which I snuck off to see at a late night screening at the Lewisham Odeon at a very tender age. Alongside Kubrick, both Bertolucci and Roeg changed the face of cinema as we know it today, each contributing their own unique cultural sensibilities to create a number of consummate masterpieces. The deliberately transgressive manner in which Roeg and Bertolucci set out to break taboos created a cinematic landscape now taken for granted in the work of Claire Denis, Pedro Almodóvar, or Lars von Trier. It is highly unlikely that we will ever again witness such a powerhouse trio capable of illuminating the celluloid firmament with the same degree of incandescent brilliance.

A 'difficult' film-maker in every sense of the term, Roeg claimed he only entered the industry because there was a small film studio near his childhood home in London's Marylebone Rd. He came to directing relatively late in his career, having worked his way up diligently through the ranks. After leaving school and completing his national service, he paid his dues by working first as a tea-boy in 1947, quickly rising to lighting gaffer and camera assistant. Just as Kubrick first learned his craft as a still photographer and Bertolucci as an assistant director on Pier Paolo Pasolini’s debut Accattone (which he described as “like being present at the birth of cinema”), Roeg directed David Lean's second unit on Lawrence of Arabia then went on to become principal cinematographer on Doctor Zhivago, Roger Corman's The Masque of Red Death, Richard Lester's Petulia,, and Francois Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451. Well aware of the specific opportunities presented by the film-making process to create great art, Roeg developed his own unique visual style, as consciously aware of the pivotal role played by editing as Orson Welles was before him - “Movies are not scripts - movies are films. They’re not books, they’re not the theatre. It’s a completely different discipline, it exists on its own. I would say that the beauty of it is, it’s not the theatre, it’s not done over again. It’s done in bits and pieces. Things are happening which you can’t get again.”

Roeg's films are nothing if not challenging, making stringent demands on the audience's intelligence that few contemporary directors have either the courage or skill to deploy. His first feature film was shelved for two years by anxious distributors and, like Performance, his second effort, Walkabout, was a commercial flop on its initial release. Both films have steadily grown in critical stature and popular acclaim. The same equivocation sealed the commercial failure of Bad Timing and Eureka, which have subsequently been reassessed as completely idiosyncratic offerings, with flashes of brilliance anchored by fabulous performances and extraordinary camera work. In a Guardian interview Roeg commented, "Well, one of my films was called Bad Timing, after all. Eureka was very bad timing. The early 1980s: Reagan and Thatcher were in, greed was good, and here was a film about the richest man in the world who still couldn't be happy. Politically and sociologically, it was out of step. Of course, The Man Who Fell to Earth was bad timing, too. Came out around the same time as the George Lucas one."

Roeg recalled his reaction after seeing Alain Resnais' mesmerizing Last Year at Marienbad, with the formal rigour of its stunning monochrome photography and wealth of spatial and temporal ambiguities. "I saw it when it came out. I thought: 'This is fantastic!' In the lobby, people were saying, 'What was that about?' The same people eighteen months later would see nothing unusual in it. Same thing now, you see? I'm not out of time. They're out of time. Even the word 'film' is obsolete. 'Grandpa, why is it called film?' 'Well, there were strips of transparent celluloid through which light was shone …' 'OK Grandpa, we gotta go … ' The retention of the image … All the subtleties in a poem, all the things you put in the rhythm of words, can be destroyed in one look." Roeg has undeniably fired off his fair share of duds, such as his made-for-TV version of Heart of Darkness (1993) and Two Deaths (1996), as well as a number of overcooked concoctions like the eerie thriller Cold Heaven (1990) and his final film, the Irish voodoo horror Puffball: The Devil's Eyeball (2009). Roeg admitted that Puffball “got mauled," but no one else could have managed it. It seemed to took an age for audiences to catch up with his ground-breaking experiments, certainly long enough to make a pioneering film-maker feel he was 'ahead of his time.' Roeg's sulky disapproval of such sentiments was palpable - "I hate that expression. I don't want to be ahead of my time. This is my time. It's Marmite, isn't it? You like it or you don't. I've done a lot of work … What difference does it make whether it's cinema? So old-fashioned. Hopefully I've got another two, three, four films left in me. But I won't be sitting here like a frozen Norwegian dog turd."

What follows is a loose assemblage of movie trivia and insider gossip about Roeg's early output (largely gleaned from IMDb, assorted interviews, and newspaper articles), rather than a detailed exegesis of their innovative technique or continuing influence. He was very much a film-makers' film-maker and extremely fortunate to find himself working at a time when formal experimentation in the industry was not only funded, but actively encouraged by the major studios in a conscious effort to recruit a younger audience away from their television sets. These days the tables have completely turned, with cable TV and the internet consistently recruiting the best young talent to produce long-form programming that pushes the boundaries of what is possible in ways that Roeg would certainly have approved. The best movies, however, still demand to be seen on the big screen to be fully appreciated - and Roeg's first four films make the case just as convincingly as those of Kubrick and Bertolucci.

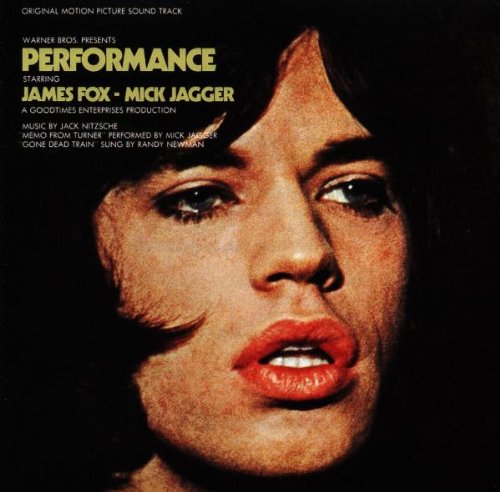

Performance

(1970), which Roeg co-directed with the sybaritic satanist

Donald Cammell, was a freewheeling road movie that stayed

put in order to delve deep into the dark recesses of the the

human mind. It remains a vivid time-capsule of late 1960s

alternative lifestyles - at once a sharp-edged razor blade

of a gangster movie and a freaked-out, psychedelic trip-fest

that plugged directly into the counter-cultural

zeitgeist, just as it was beginning to become bleary,

bloated, and cynical. James Fox was a revelation as Chas, a

London gangster on the run who undergoes an identity crisis

while holed up in the dilapidated Powis Square basement

squat of a reclusive rock star played with superb aplomb by

Mick Jagger, in his first film role. This cinematic

exploration of violence and psychic disintegration was

partly inspired by the writer Jorge Luis Borges, to whom

references abound in the movie, including a brief shot of

his portrait near the end.

Throughout his career, Roeg had a knack for surrounding himself with talented actors and collaborators. When he teamed up with Cammell to work on Performance, the latter already had a reputation as a charismatic artist in his own right. The decadent dependent of a Scottish shipyard dynasty was raised in an environment he described as "filled with magicians, metaphysicians, spiritualists, and demons.” His great-great grandfather made a fortune in steel and shipping and, in the heyday of the Cammell-Laird empire, the Cammells became one of Britain's wealthiest families. Donald's father inherited the fortune at the age of fourteen, but lost most of it in the 1929 stock market crash. By the late thirties, the family had moved from Scotland to London and were living in Richmond, across the Green from Aleister Crowley, who used to draw up 400-page horoscopes for the children and about whom his father wrote a book. Barbara Steele, the cult horror movie actress Cammell seduced when she was still an art student, described him as a Pan-like creature - "You half-expected him to have a little tail." Watching him playing Isis in Kenneth Anger's Lucifer Rising, with his face daubed green and dressed up in ancient Egyptian garb, you could be forgiven for imagining that he had landed on Earth from some far distant planet, but in fact he came from a conventional upper middle-class background, attended Westminster school, and was a precociously gifted painter. He won a scholarship to the Royal Academy at the age of sixteen and made a name for himself in the mid-fifties painting technically accomplished, but conventional portraits of society figures. The bohemian charms of Chelsea's King's Rd beckoned and he moved into a studio in Flood St. which became a safe haven where the aristocratic 'in' crowd, including society photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones, could mix freely with more seedy characters such as the junkie poet Alexander Trocchi. He broke into the film business with an appalling excuse of a screenplay for a caper movie starring James Coburn and James Fox called Duffy, which landed like a lead balloon. The experience was so frustrating that he decided to direct his next script himself, went in search of an experienced cinematographer, and linked up with Roeg. Cammell was a louche 'rogue' himself, who got his kicks from manipulating those around him, befriended Anita Pallenberg, and hence infiltrated the Rolling Stones' orbit. A frustrated under-achiever, he was sixty-two when he finally shot himself in the head in his Los Angeles hillside home, echoing Chas' demise in a suitably dramatic gesture that squared the circle on a decidedly ungodly existence.

Prior to the start of production, it was Cammell who arranged for Fox to spend time training in an East End boxing gym with professional criminals to help prepare his character. Some of the minor members of Flowers' gang were real villains and David Litvinoff (credited as dialogue coach and technical advisor) actually handled mob liaison to make sure Fox avoided getting into any real trouble. Cammell was influenced by Antonin Artaud's theories on the link between performing and madness, allegedly encouraging both cast and crew to take drugs during the shoot and mingle sexually to help create an authentic atmosphere of debauched depravity. Apparently he didn't need to push very hard. One scene actually shows Anita Pallenberg shooting up heroin, which she and Keith were just starting to experiment with at the time, while Michelle Breton, the third in the famous bath scene who used to be paid to 'perform' as a couple with her boyfriend, had to have Valium shots before every take. Before hooking up with Richards, Pallenberg dated Brian Jones, who partly inspired the character of Turner. According to his autobiography Life, Keith claimed the sex scenes between her and Mick didn't phase him - “You've got an old lady like Anita … and expect other guys not to hit on her? … Anyway, she had no fun with his tiny todger.” Nevertheless, Keith lurked outside the set in a foul mood when he wasn't sneaking off behind Mick's back to score with Marianne Faithful. The whole experience completely disorientated Fox, who started talking like a Bermondsey gangster both on and off set and had a nervous breakdown afterwards - “until he was rescued by the Navigators, a highly suspect Christian sect that claimed his attention for the next two decades.”

Some of the 16mm footage of the sex scenes were so explicit that the film processing lab refused to develop it, referring to obscenity laws, and instead went on to destroy it with a hammer and chisel. At the first test screening in Santa Monica in March 1970, one Warner executive's wife vomited and most of the audience walked out. According to Roeg, another Warner executive said of the scene depicting Jagger in the tub with Pallenberg and Breton, "Even the bath water was dirty." The release was delayed for two years while it was re-edited three times by Frank Mazzola, whose style of rapid montage and jump cuts later became his trademark. Reviews were varied, with John Simon of New York magazine writing that it was "the most vile film ever made.” In fact, Roeg's first directorial offering was a brilliant combination of sinister violence, gender-bending androgyny, and hallucinatory psychedelia, accompanied by a wonderful Jack Nitzsche soundtrack that included tunes by the Rolling Stones, Ry Cooder, and the revolutionary black rappers who called themselves the Last Poets. The visceral power of music and the celebrity image of iconic rock musicians continued to play a central role in the creation of Roeg's cinematic universe, especially when he came to direct The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Walkabout

(1971) was also a sexually and spiritually transgressive

movie, a visionary tale of two schoolchildren abandoned in

the Australian outback by their suicidal father who only

survive with the unlettered bush wisdom of an aboriginal

boy. Roeg worked with the dramatist Edward Bond on adapting

Donald G. Payne's novel and created an idyllic depiction of

a disappearing indigenous culture, an elegy of lost

innocence, and a savage indictment of repressed Antipodean

conventionality and stultifying social conformity. The

film's dialogue was largely improvised, with Bond's

screenplay only fourteen pages long, and ends with the

epigraph from A.E. Houseman's lyrical poem quoted above.

Film trivia: the teenage Jenny Agutter was so embarrassed

when filming the scene of her swimming naked, that Roeg

reduced the film crew down as much as possible (when

shooting was over, they returned and all went for a nude

swim together); David Gulpilil spoke no English at the time

of filming; and Roeg's son Luc was so badly sun-burnt that

the scene in which Gulpilil treats his back by rubbing him

with fat from a wild boar was not faked.

Don’t Look

Now (1973) is about an alienated and unhappy couple

trying to cope with the loss of their daughter in an

accidental drowning and how she later reappears in Venice to

haunt them. Roeg insisted that Christie attend a séance

prior to filming. Leslie Flint, a Notting Hill medium,

invited them to attend a session he was holding for some

American parapsychologists, so Roeg and Christie went along

and sat in a circle in the pitch dark and held hands. Flint

instructed his guests to "uncross" their legs, which Roeg

subsequently incorporated into the film. The image of

Sutherland crying out in agony as he heaves the dead girl's

body out of the water is as memorable as the supernatural

encounters among the mist-shrouded canals. His fear and the

grief are palpable, augmented by an irrational chill that

accompanies the telepathic sense that something is seriously

wrong between him and Julie Christie well before the tragic

event occurs. Roeg told Peter Bradshaw a disturbing anecdote

about the opening scene: every time the girl sank below the

water’s surface, her father jumped into the water to save

her. No matter how vehemently Roeg assured him it was

completely safe, the man had to be physically

restrained.

For all their formal innovation and haunting, oneiric narratives, Roeg’s films are all extremely passionate, visceral experiences. In his magisterial control of shooting and editing, he bears comparison with both Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock, but in the 'progressive' seventies, when film censorship was considerably relaxed, Roeg could be much more candid about sex and human relationships. The intensely erotic scene in the hotel room between Christie and Sutherland, in which shots of their lovemaking are intercut with glimpses of them getting dressed afterwards, splices together their steamy rumpy-pumpy and its languorous aftermath in a kind of inverted foreplay. As Peter Bradshaw pointed out, it is a rare example of a mature sex scene in which the participants are not making love for the first time. These are clearly two adults who already know each other intimately. Years later, Sutherland described how shooting the sex scene was hardly erotic for those involved at the time. He and Christie were on set at 7 AM in dressing gowns, waiting downstairs while the room was prepared and drinking champagne to calm their nerves. Roeg and his cinematographer Anthony Richmond each operated their own Mitchell 35mm cameras as Sutherland and Christie disrobed and got onto the bed. The walls were oak-panelled and the cameras were unblimped, immensely amplifying the noise in the room. Over the racket caused by the huge cameras, Roeg began shouting directions to Sutherland such as "lick her nipples," "put your hand between her legs," and "get on top.” The shoot lasted well into the afternoon before he was finally satisfied and called a wrap. The scene also serves an important function within the film's narrative arc, since it was Roeg’s contention that it marked the moment at which Christie becomes pregnant again. Though this is never mentioned explicitly in the movie, he considered the final shot of Christie in the funeral procession as a moment signalling an imminent birth. Only a film-maker of Roeg’s talent could have created such an emotionally authentic scene in the midst of such a cacophony - and then have the audacity to place it in the middle of a truly terrifying movie.

Filming the scene in which Sutherland almost falls to his death while restoring the church mosaic was similarly beset by problems and resulted in Sutherland risking his life. The scene entailed some of the scaffolding collapsing, but the stuntman refused to perform the stunt because the insurance was not in order. At Roeg's insistence, Sutherland ended up doing it himself and was attached to a kirby wire as a precaution in case he should fall. Stunt co-ordinator Vic Armstrong later told Sutherland that the wire was not designed for that purpose, and the twirling around caused by holding on to the rope would have snapped it if Sutherland had let go. Finding an appropriate church was itself a struggle. After visiting most of the churches in Venice, the location manager suggested constructing one in a warehouse. The discovery of San Nicolò was particularly fortuitous since it was currently being renovated and the scaffolding was already in place. Originally intended to show the distance between Sutherland's deep denial and Christie's guilty inability to let go, the scene in which Christie lights a candle for her daughter was largely improvised. The original script included two pages of dialogue intended to illustrate his intense unease at her overt display of grief, but after a break in filming, Sutherland returned to the set and commented that he did not like the church, to which Christie retorted that he was being "silly" and the church was "beautiful." Roeg felt that their exchange was more realistic in terms of what the characters would actually say to each other, so he opted to include their improvised exchange instead.

Pino Donaggio was picked as the film's composer after one of the producers had an inspiring vision when he saw Donaggio riding on a gondola during location scouting. The only disagreement over the musical direction of the film was for the score accompanying the love scene. Donaggio composed a grand orchestral piece, but Roeg wanted it toned down. In the end the scene used a combination of piano, flute, acoustic guitar, and double bass. Donaggio conceded that the more low-key theme worked much better and ditched the strings, reworking them for the funeral scene at the end of the film. Film trivia: the lyrics from Big Audio Dynamite's E=MC2 comment on the film - “Met a dwarf that was no good / Dressed like little Red Riding Hood / Bad habit taking life / Calling card a six inch knife / Ran off really fast / Mumbled something 'bout the past / Best sex I've ever seen / As if each moment was the last / Drops of blood color slide / Funeral for his bride / But it's him who's really dead / Gets to take the funeral ride.”

The Man Who Fell

to Earth (1976) was another unclassifiable masterpiece,

which, like Performance, was enhanced by the charisma

of a rock star - in this case, David Bowie as Thomas Jerome Newton, an intergalactic visitor to Earth on a mission to save his own drought-stricken planet. It is a glorious concept album of a film, with riveting performances by Rip Torn, Buck Henry, and Candy Clark (who was romantically involved with Roeg at the time), in which Bowie manages not be upstaged in his film debut. The scene in which he faints and has to be carried into his

hotel room has a bizarre, fetishistic eroticism that no

other director could begin to approach. Apparently, Clark

was not really carrying Bowie; instead, a rig involving a

skateboard and a bicycle seat was devised that enabled the

actress to look like she was carrying him.

Screenwriter Paul Mayersberg adapted Walter Nevis' 1963 novel, in which Terry Southern enjoys a cameo as a reporter at the space launch. Tevis described his story as a disguised autobiography that included long periods of sickness during his childhood which confined him to bed, his battle with alcoholism, and his family's move from San Francisco to rural Kentucky. The Boston Globe's James Sallis described the film as a Christian parable, not only about the corruption of an innocent being, but also highly critical of the 1950s conventionalism which Tevis grew up with, along with environmental destruction, and the Cold War. At the beginning of the film, we see a mysterious man in a suit who investigates Newton's original landing on Earth. Exactly who he or what agency he works for is never explained, although there are hints that the US government knew all along that Newton was an alien. In a reference to Bowie's Ziggy Stardust persona, the name of the record album that Newton recorded and is seen at the end of the movie was The Visitor. There are a number of other similarly neat meta-textual touches: the music that Farnsworth is listening to in his first scene (and again in one of the last) is Gustav Holst's The Planets; while toward the end of the film Bryce walks past a record store display for Bowie's Young Americans album.

Paramount Pictures paid $1.5 million for the US distribution rights , which enabled the film's producer Michael Deeely to finance the picture, which had a production shoot of only eleven weeks. There were variety of production problems. At one point, Bowie was unable to work on the movie for two days because he had drunk some "bad milk" and saw "some gold liquid swimming around in shiny swirls inside the glass". Clark, wearing a large black hat strategically pulled low over her face, was recruited to play Newton. According to the 'Bowie Golden Years' website, Bowie remained “unsure of what actually happened. No trace of any foreign element was detected in tests though there were six witnesses who said they had seen the strange matter in the bottom of the glass. Already in an extremely fragile state, Bowie felt the whole location had 'very bad Karma'.” While filming at an old Aztec burial ground in the New Mexico desert, the production had to deal with some boisterous Hells' Angels camping nearby and cameras frequently jammed during principal photography for no explicable reason. The film spent roughly nine months gestating in the editing suite, and when studio head Barry Diller saw Roeg's first cut he refused to pay for it, claiming it was different from the movie the studio had contracted. British Lion sued Paramount and received a small settlement. The film obtained a small release in the US through Cinema V in exchange for $850,000 and due to foreign sales the film's budget was just recouped.

In an 1982 article in Movieline magazine, Bowie is quoted as saying, "I just threw my real self into that movie as I was at that time. It was the first thing I'd ever done. I was virtually ignorant of the established procedure [of making movies], so I was going a lot on instinct, and my instinct was pretty dissipated. I just learned the lines for that day and did them the way I was feeling. It wasn't that far off. I actually was feeling as alienated as that character was. It was a pretty natural performance. ... a good exhibition of somebody literally falling apart in front of you. I was totally insecure with about ten grams [of cocaine] a day in me. I was stoned out of my mind from beginning to end". According to costume designer May Routh, Bowie was so thin that some of his outfits were boys' clothes. Kurt Loder quoted Bowie in a 1983 Rolling Stone article - "I'm so pleased I made that [movie], but I didn't really know what was being made at all".

Despite his spiralling intake of cocaine, Bowie said of his relationship with Roeg - "We got on rather well. I think I was fulfilling what he needed from me for that role. I wasn't disrupting . . . I wasn't disrupted. In fact, I was very eager to please. And amazingly enough, I was able to carry out everything I was asked to do. I was quite willing to stay up as long as anybody.” Bowie worked on a soundtrack for the film which was rejected and, due to a creative and contractual dispute with Roeg and the studio, has never been released, even though the 1976 Pan Books paperback edition of the novel (released to tie in with the film) states on the back cover that the soundtrack is available on RCA. According to Bowie in several subsequent interviews, there were never any plans to release a soundtrack album and he had no desire to undertake the effort due to the complex legal entanglements. Many of the ideas he had for the soundtrack would later be utilized on Low (1977), while production stills were used in the cover art for that album, as well as for Station to Station (1976).

Bad Timing (1980) is another transgressive and challenging masterpiece which at the time upset moralists and thrilled cinephiles. Again, there are extraordinary performances from both Harvey Keitel and Art Garfunkel, who plays an American psychiatrist who becomes obsessed with the delectable Theresa Russell (and who could blame him?). The agony of their relationship is revealed in a series of disordered scenes that strongly suggest necrophilia. British distributor Rank had started out distributing religious films and when George Pinches, who was head of the Rank circuit, saw the film he called it, “a sick film made by sick people for sick people.” The title is not only an ironic comment on Roeg’s audacious attitude to narrative structure and the use of flashbacks, but also on the tragic flaw of contemporary culture - the consequence of diminishing attention spans when the times are literally and figuratively “out of joint.”

A string of less accomplished, but equally quirky films followed throughout the eighties, as studios started to cut back on the number of 'art house' productions and aim directly at the market for adolescent blockbusters. Roeg struggled to find financing for his more adult vision of what constituted popular 'entertainment,' but never compromised in his choice of disturbing and off-beat subject matter. If Bad Timing was ambiguously and provocatively Shakespearian in this sense, Eureka (1983) was more a Jonsonian parable of human misery, which is perhaps why it has remained one of Roeg's most underrated films. The twin themes of alienation and alcoholism are recombined in a story based on the unsolved murder of Sir Harry Oakes, the self-made millionaire who was bludgeoned to death in his luxurious Bahamanian home in the midst of WWII. Gene Hackman played the stingy plutocrat whose wealth has been transmuted through an anti-alchemy of greed and paranoia into an unending dread that everyone is after his money, while Rutger Hauer and Kristin Scott-Thomas provided stellar back-up in this voodoo and rum-soaked escapade. Her classic line “lay off the sauce” was delivered as though written by a goose quill dipped in venom.

Insignificance (1985) assembled Gary Busey, Tony Curtis, and Theresa Russell in bizarre adaptation by Terry Johnson of his surreal stage-play. It is a fantasy drama about Marilyn Monroe meeting Albert Einstein in a hotel room, with Joe McCarthy and Joe diMaggio playing second fiddles, known only as The Actress, The Professor, The Senator, and The Ballplayer. Einstein is wracked by guilt over Hiroshima, yet fancies the simplicity of a sexual liaison with Marilyn, who is sick of being seen as a bimbo and craves intellectual credence. McCarthy is at the height of his witch-hunting powers, but depicted as an impotent sleazebag, while DiMaggio is insecure about his celebrity, self-obsessed, and prone to violence. Each character contains the seeds of their own destruction, with a troubled, abused/abusive past behind them and a questionable future ahead. Gradually, destructive obsession remerges as Roeg's central theme - not only America's national obsession with its postwar cultural icons and mores, but also the characters' private obsessions about achieving an apparently unattainable state of acceptance and serenity. Compared with the general theory of relativity, a proposed unified-field theory, or indeed the cosmos itself, all their aspirations and interactions are totally insignificant. Yet these aspects of the physical universe affect us all directly when they are applied to developing the means to destroy the entire planet. Monroe's mention of the principle behind the neutron-bomb is not an anachronism per se, but its significance can only be completely understood by a contemporary audience.

Track 29 (1988) was a sensually charged Dennis Potter drama, again starring Russell and mostly confined to a single location. When Gary Oldman shows up looking for his long-lost mother, we know everything and everybody will soon spin off the rails and get smashed up. Castaway (1986) starred Oliver Reed (who claimed he went on a vodka diet to lose weight for the film) as a middle-aged misogynist who advertises in a London paper for a female companion to spend twelve months with him on a desert island. After a couple of meetings, Amanada Donohoe agrees to go ahead, but once on the island things prove less than idyllic, and it becomes increasingly clear that she is the one who really has the strength and desire to see the year through. The original uncensored version showed her in complete full frontal nudity in many scenes, with long lingering shots that lent a decidedly creepy, voyeuristic atmosphere to the whole affair. The Witches (1990) was a deliciously amsuing adaptation of the Roald Dahl tale, with Anjelica Houston and special effects provided by Jim Henson's workshop. Suzanne Moore neatly summed up Roeg's ability to impact audiences - “When Anjelica Huston rips her face off … the audience gasps. But there are such moments in each of his films that send us spinning: Jenny Agutter’s hand on black skin, Art Garfunkel’s penknife, Mick Jagger’s slicked-back hair, Bowie removing his contact lenses. Whatever the source was, Roeg tapped it, drank deep and showed us shards of it that will never leave our memory.”

Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At South Bay And Peketā Beaches And Kahutara River Upstream Of SH1

Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At South Bay And Peketā Beaches And Kahutara River Upstream Of SH1 Wikimedia Aotearoa NZ: Wikipedian At Large Sets Sights On Banks Peninsula

Wikimedia Aotearoa NZ: Wikipedian At Large Sets Sights On Banks Peninsula Water Safety New Zealand: Don’t Drink And Dive

Water Safety New Zealand: Don’t Drink And Dive NZ Olympic Committee: Lydia Ko Awarded Lonsdale Cup For 2024

NZ Olympic Committee: Lydia Ko Awarded Lonsdale Cup For 2024 BNZ Breakers: BNZ Breakers Beaten By Tasmania Jackjumpers On Christmas Night

BNZ Breakers: BNZ Breakers Beaten By Tasmania Jackjumpers On Christmas Night Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At Roto Kohatu Reserve At Lake Rua

Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At Roto Kohatu Reserve At Lake Rua