The Glory That Was Greece, And The Grandeur That Was Rome (Part One)

On desperate seas long wont to roam,

Thy

hyacinth hair, thy classic face,

Thy Naiad airs have

brought me home

To the glory that was Greece,

And the

grandeur that was Rome.

- Edgar Allan Poe, To

Helen.

To Helen is the first of two poems

with that title written by Poe which allude to the story of

Helen of Troy. Poe's 1845 revision made several rhythmic

alterations to his original poem, most notably improving

"the beauty of fair Greece, and the grandeur of old Rome" to

read "the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was

Rome." In Greek mythology, Helen was born from an egg, the

daughter of Zeus and Leda, and her personification of ideal

beauty has inspired such varied artists as Guido Reni,

Tintoretto, and Gustave Moreau. Two lines from Christopher

Marlowe's tragedy Doctor Faustus (1604), derived from

Lucian's satirical Dialogues of the Death, are

frequently cited in this respect:

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Poe was citing Sappho, the lesbian poet

who lived c. 630-570 BC, and who had similarly compared the

ideal of female beauty to a fleet of ships. His phrase "Like

those Nicean barks of yore" echoes a line from Samuel Taylor

Coleridge's poem Youth and Age ("Like those trim

skiffs, unknown of yore"), while adding a reference to the

French city of Nice, the location of a major Mediterranean

shipyard where Marc Antony outfitted his fleet. Poe also

suggests an affiliation between Helen and Psyche, the

beautiful princess who became Cupid's lover and represented

the soul to ancient Greeks. In a few verses of highly

condensed lyricism, he thus invokes the entire Greek

heritage from which so many of our Western ideals of beauty,

democracy, philosophy, and learning were derived.

But how exactly can Helen be said to embody Psyche? And who precisely is the wanderer coming home?

Having recently returned from a six-week sabbatical, visiting Athens, Delphi, Rome, Siena, Pisa, and Florence, I would like to offer a few observations on the wealth of Classical and Renaissance art and literature to which I was exposed. Contemporary visitors, if they are able to endure the verminous throngs of tourists infesting the Vatican Museum and Uffizi Galleries, often leave feeling exhausted and drained. The attempt to assimilate such sumptuous manifestations of concentrated power, prestige, and privilege assembled by various voracious family dynasties (enriched by highly exploitative banking, investment, and insurance operations) is similar to the sensation we might experience after indulging in a sacrificial feast to the Gods - somewhat akin to digesting an eight-course banquet of artistic haute-cuisine. I returned feeling gorged, glutted, and slightly nauseated by the overwhelming and ostentatious opulence on display. What follows are eight random, but interrelated reflections on the inspiration behind all that glorious grandeur.

The

Homeric Paradigm

She looked over her

shoulder

For ritual pieties,

White

flower-garlanded heifers,

Libation and

sacrifice,

But there on the shining metal

Where

the altar should have been,

She saw by his flickering

forge-light

Quite another scene.

- WH Auden,

The Shield of Achilles.

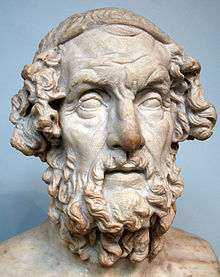

The best starting point to begin any cursory investigation into the Classical World is with the twin verse epics compiled by Homer - the blind poet who may or may not have actually existed, but to whom is attributed the assemblage of ancient tales that constitute his Iliad and Odyssey. Recent scholarship has placed Homer's composition somewhere between 750 and 730 BC, certainly well before the poet Hesiod. Although the formative years for his heroic stories were between 1050 and 850 BC, when literacy had been lost and the Greeks had not yet adopted the Phoenician alphabet, the social world he described in his poems is thought to have existed around 800-750 BC.

Homer's influence continues to loom over Western literature, rather like some meddling god from Olympus. The Iliad supplies a highly dramatic insight into a heroic world whose reality has never faltered - not only as seen through his striking use of similes, where kings feast under the shade of oak trees, children build castles of sand, and old women watch from their porches as wedding processions dance by, but also through the leisurely progress of a narrative rich in chiastic and repetitive phrases. Homer relates a series of epic struggles in which a series of muscular heroes strive for glory, knowing that death is inescapable; where ivory-limbed Andromache laughs through her tears and heats the bath water for her husband Hector, even though she realizes he will never return to their megaron; and gods and goddesses are no more remote for being omnipotent, Apollo even raining down bloody tears and creating a carpet of fragrant hyacinth after the accidental death of a Spartan prince, just as Ovid's Venus, finding herself unable to revive the drooping Adonis, mingled her tears with his blood, creating anemones which ever since have been considered emblems of sorrowful remembrance.

There is something peculiarly vital in Homer's 2,700-year-old tales, which provided Western culture with its first novel, its first extended epic, and its first odyssey - quite different from the Iliad, whose more formal universe consists of battles, rivalries, and cultures in extremis. While the Iliad is a largely an account of a society riven by warfare, Odysseus is barely part of a society at all. His crew rebels and his wife's suitors overrun his home while he spends a year in sybaritic indulgence, and another seven held captive by Calypso. He is repeatedly left isolated and his frequently mentioned trickery (echoed by the twists and turns of Homer's narrative) is a bemused response to this world of uncertainty. Nothing can be relied upon, not even the old modes of heroism. In many ways, Odysseus is the first anti-hero, leading his men into needless danger, compulsively spinning out lies, and testing his listeners' loyalties. There is something very modern about his ever-present sense of solitude and loss, his copious tears. Whether listening to the Sirens or passing by the Lotos eaters, he constantly struggles against the temptation to cease struggling, to sink into an erotic or drugged oblivion. Such dangers are overcome painfully, as he finally manages to reclaim his social roles as father, husband, son, and king. The perils faced during his journey home from the Trojan wars have been passed from generation to generation - the rival cataclysms offered by Scylla and Charybdis, the alluring temptations of the Sirens and Circe, and the cannibalism of the Cyclops. What quest has not followed a similar path, strewn with tests and failures, lures and obstacles, personal destiny mixed with bewildering freedom?

Renaissance, Neoclassical, and Romantic movements have all drawn direct inspiration from the templates Homer originally provided, and each era has created its own version. In one fascinating anthology, George Steiner chronicled a near-millennium of English renditions, refractions, and reflections of the original. His unrhymed, but intensely rhythmic dactylic hexameters have not only been turned into heroic couplets by Alexander Pope, but also popular songs like the one Lawrence Durrell imagined Odysseus singing to Circe in A Homer for the 90s:

You're bringing out the swine in me

By giving

too much wine to me

Though all your promises sound fine

to me

But Circe, I simply gotta go.

Homer's lasting relevance can be traced from Virgil's Aeneid and Dante's Divine Comedy, through Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida and the various 'Roman' plays, to successive English translations by such poets as George Chapman, Pope, and Dryden, all the way down to James Joyce (who amended Homer's image of the "wine-dark sea" to "snot-green" in his own version of Ulysses), and even episodes of Star Trek and The Simpsons, which named its main character after him.

Until relatively recently, Latin and Greek were compulsory subjects in the English educational system. The careers of three famous nineteenth-century poets, all of whom were raised in Homer's figurative and literal shade, illustrate the enduring appeal of his language and subject matter. The cryptic rhetoric of Chapman's Elizabethan translation left John Keats (author of Ode to A Grecian Urn and Ode to Psyche) a life-long admirer, like a ''watcher of the skies'' discovering a new planet, up until the end of his life in 1821, when he died in small bedroom located next to the Spanish Steps in Rome. The following year, Percy Bysshe Shelley (author of Adonais, Hellas, and Prometheus Unbound), drowned in a sudden storm on the Gulf of Spezia that engulfed his sailing boat, the Don Juan. The name had been suggested by the historian Edward Trelawny as a compliment to the arch Hellenophile Lord Byron, who also travelled extensively throughout Italy and Greece, living for seven years in Venice and Ravenna, and hanging out with Shelley's literary circle in Pisa.

Byron himself became a bitter critic of Lord Elgin's removal of the Parthenon marbles from Athens after he saw the spaces left by the missing friezes and metopes, and denounced Elgin personally in The Curse of Minerva and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Such was his commitment to classical ideals that he died in 1824 from a fever contracted while fighting in the Greek War of Independence. Shelley's ashes were interred in Rome's Protestant Cemetery near an ancient pyramid outside the city walls which already housed the remains of Keats, but whereas Keats' grave does not mention his name (simply the lines "Here lies one whose name was writ in water"), Shelley's bears the Latin inscription Cor Cordium (Heart of Hearts) and three lines from Shakespeare's play The Tempest, referring to his death at sea:

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Such prominent American authors as James Fenimore Cooper, Edith Wharton, and Henry James later spent extended periods of time living and writing in Italy. Sigmund Freud obtained profound insights into the workings of the unconscious from his studies of Greek mythology, to the extent of naming his two most famous psychological complexes after Oedipus and Electra. Twentieth-century writers Patrick Leigh Fermor and Lawrence Durrell both wrote many wonderful books inspired by their explorations of and experiences in Greece, while modern translations of Homer, Ovid, and Dante all continue to proliferate. Most recently, the classically trained celebrity wit and polymath Stephen Fry has got into the act, publishing his own abridged version of Greek and Roman myths. These reverberations continue to resonate throughout the Western literary canon, their inspiration deriving explicitly from the epic narratives first compiled by Homer, who provided the paradigm that has shaped so much of our literary heritage.

Such cultural echoes are not confined to literature, however. One of the most striking aspects of Italian Renaissance painting, architecture, and sculpture is the debt it owes not only to Biblical stories and religious iconography, but also to the enduring 'pagan' myths and legends of Ancient Greece and Rome. Papal palazzi teem with a plethora of scantily-clad dryads, naked nymphs, and bearded satyrs. Dimpled cupids and cherubic pink putti constantly hover above, while sea nymphs and nereids patrol the subaqueous depths below. The labours of Heracles provided a similarly inexhaustible source of inspiration for Quattrocentro interior designers of wall panels and decorators of ceiling frescoes. Despite the Old Testament prohibition on graven images, the Popes and Doges of Rome, Florence, Mantua, and Venice had no qualms about exhibiting copious quantities of naked flesh in a religious context.

It took the Puritan Reformation to put a stop to such voyeuristic pleasures being purveyed in churches (and the non-representational sterility of Abstract Expressionism to reject the claims of narrative entirely), but both wealthy English aristocrats and self-made American millionaires persisted in their Grand Tours of Europe. During a period when there were no effective export controls, they scoured the homes and gardens of impoverished grandees, often for months, even years at a time, purchasing and pillaging vast collections of art and artifacts to adorn the walls of their stately homes and colossal variations of Hearst Castle. When they could not buy the originals, they commissioned copies and replicas, just as the Romans had before them. We need only compare the extraordinary purity of early Cycladic sculpture which flourished in the islands of the Aegean from c. 3300 to 1100 BC with the work of Picasso, Modigliani, Brancusi, and Moore to appreciate the influence this Ancient Greek art form exercised on twentieth-century Modernism.

The classical Greek heritage from

Homer onwards has continued to provide both motive and

inspiration for countless painters, sculptors, and

architects, in addition to a variety of prototypical

scenarios for novelists, playwrights, and poets that remain

vital and relevant many centuries later.

The Paradox of the Greek Gods

Now is the time to depart, for me

to die, for you to live, but which of us is going to the

better business is unclear to all, except God.

- Plato's

'Socrates' to his jury, Apology, 42A.

Much like contemporary Hollywood superheroes, in whom we see our own desires and appetites incarnated, Homer's gods and goddesses are as petty and vindictive as any of the human beings whose actions they seek to influence. The Greek and Roman deities all have historical axes to grind, carry heavy chips on their shoulders, and often appear astonishingly childish in their paltry rivalries, puerile squabbles, and personal vendettas. Constantly swayed by anger, jealousy, resentment, and envy, they are prone to violent temper tantrums whenever they fail to get their own way. Zeus (Homer's thundering "storm-bringer") notoriously metamorphosed himself into various animal forms in order to impregnate a succession of unwitting and reluctant women; while according to Book 11 of the Odyssey his brother Poseidon (the "earth-shaker") swept one of his many conquests away in the folds of a purple wave. When offended or ignored, the temperamental sea god struck the ground with his trident, causing chaotic earthquakes, shipwrecks, and multiple drownings.

The gods might just as easily dote over a boy as a girl (as Zeus loved Ganymede, or Apollo the hapless Hyacinthus), but their female lovers are always virgins. They invariably get them pregnant and if a god makes love to a woman twice in succession, she has twins. They demand continuous ritual sacrifices in order to influence and appease their fickle natures. They seem to enjoy all the smoke and are content to receive the fat and bones (although apparently Aphrodite did not like pork), while the mortals below save the best cuts of meat for themselves. Not only are they located below the earth and the oceans, where blood and libations are poured and animals totally incinerated (hence the word 'holocaust'); they also exist in the sky above, in which case the animal's meat is more wisely shared.

Greek divinities did not simply kick back, however, quaffing prodigious quantities of ambrosial nectar on Mount Olympus, their "shoulders mantled in unbroken cloud," as Homer put it in Book XX of the Iliad. Greek life was imbued with a sense of their constant presence, whether in the terrifying clamour of littoral typhoons, the anguish of unfathomable diseases, the dust clouds raised by racing charioteers, or on remote Arcadian hillsides sweltering in the midday sun. "Not to everyone do the gods appear," Homer admitted, but they were most accessible at night, in dreams, and at the numerous oracular shrines which peppered the landscape. The reputation of the most famous of these, the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, was established in the eighth century BC. On a few auspicious days a priestess would drink toxic doses of fresh honey and chew 'daphne,' then reply on the gods' behalf to questions put by visitors bearing tribute. These responses were given in prose or hexameter verse, but since Apollo enjoyed a peculiar sense of humour they were also notoriously ambiguous and perplexing.

While Greek mythology teems with stories of divine intervention, their appearance was much less frequent during the formative years of Roman history. Whereas art, and especially sculpture, gave physical embodiment to the Greeks' image of their superhuman gods, the Roman scholar Varro reckoned no statues of their gods were made until 750 BC. Nonetheless, many underlying principles were shared. Like the Greeks, the Romans were polytheists and their divinities had Latin names that could easily be equated with Greek ones. As in Greece, the main aim of a religious cult was to ensure worldly success, not save people from sin. The Roman concept of an eschatological future life was as shadowy as that of the Greeks. Whether pursued by pouring libations, sacrificing oxen, or offering first fruits at country altars, the primary purpose of worship was honour and appeasement. Virgil in his pastoral Georgics mentions the simplest of all offerings - garlands of Michaelmas daisies displayed on turf altars in the countryside.

Carnivorous and sanguinary, riven with factionalism and cliques, prone to lust, vanity, and adolescent fits of pique, the Greek and Roman gods are neither paragons of virtue nor dignified and enlightened beings who personify divine transcendence. In many ways they come across as both familiarly flawed and remarkably human.

Herodotus and the Wheel of Fortune

When

they had finished dining, they had begun the drinking and

the Persian said as follows to the Greek … 'My friend, no

man can turn aside what must come about by God … Many of

us Persians know this but we follow, bound by necessity.

This is the most hateful anguish of all among men, to

understand much and to prevail in nothing.'

- Herodotus,

The Histories, Book IX.

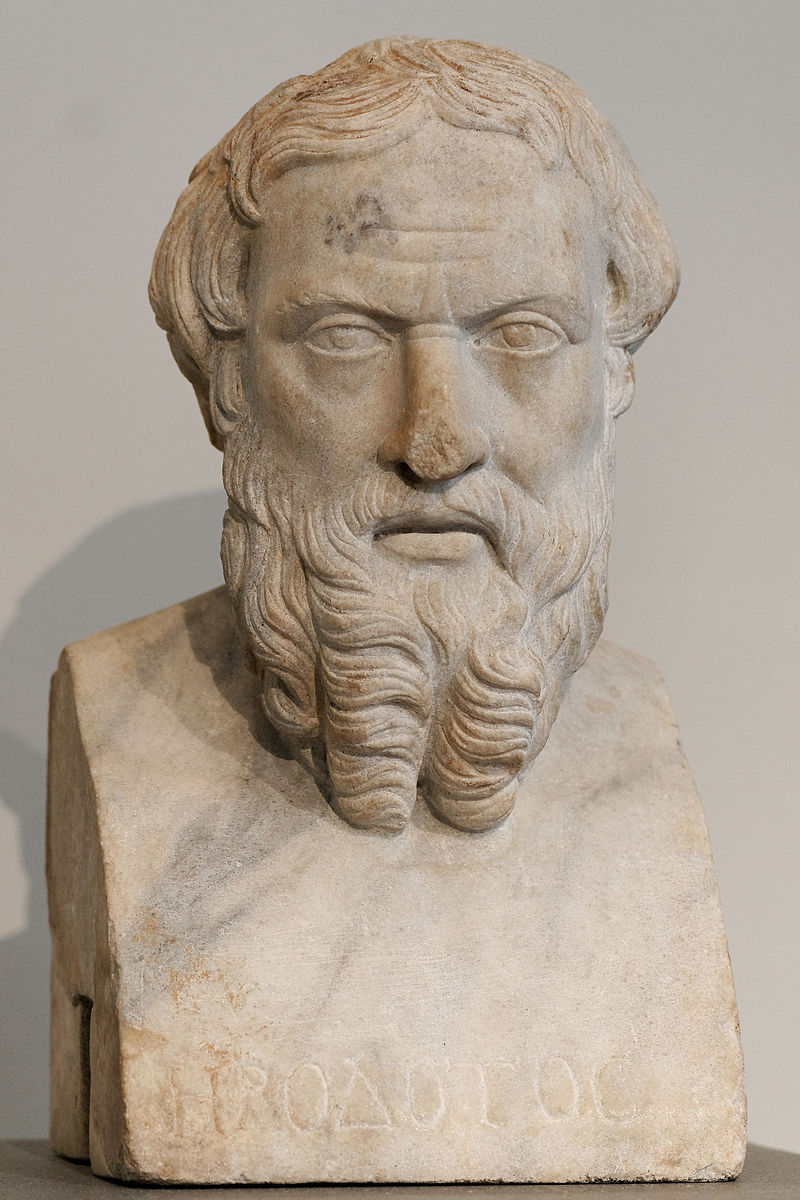

Even more explicitly than Homer's chronicle of the Trojan war and its aftermath, the historian and ethnographer Herodotus (c. 490-425 BC) delineated the wider contours of the Greek world view. He set out to explain and celebrate the great events of the Persian Wars against the Greeks, an enterprise that lead him on long digressions both literary and personal. Like the best anthropologists, he traveled extensively and his main evidence was oral, what people in different places told him when he questioned them. Whenever possible, he used empirical observation ('autopsy') for geographical information, buildings, monuments, artworks, and the observance of customs. But for past deeds and for people who lived at the edge of the known world, he turned to what reliable informants had to say, always remaining sceptical, explicitly qualifying his role as simply recording "what is said," and cautioning that he reports more than he believes to be true (Books II and VII).

The Egyptians had preserved extensive archives of their past and the Persians possessed a vast bureaucracy, but Herodotus often had to fall back on intermediaries, for there is no evidence he knew any language other than Greek. Where direct evidence was lacking, he used reasoned inference and sometimes more tenuous opinions. He also drew on literary sources, such as the poems of Aristeas (an early Greek explorer of central Asia around 600 BC), Aeschylus' Persians (produced in Athens in 472 BC), and Phrynichus' Fall of Miletus, which recounted that city's fate at the end of the Ionian revolt in 494 BC. Although he referred to Hecataeus of Miletus by name in Book V, Herodotus lifted descriptions of the crocodile, hippopotamus, and phoenix from Circuit of the Earth, and misrepresented his source as "Heliopolitans" (Book II). The author of two works rather different in character, but both of profound importance for the future of historical writing in Greece, Hecataeus (c. 500 BC) tried to bring order to the various and contradictory genealogies that existed in the Greek mythic tradition. Unlike Herodotus, however, he did not record events that had occurred in living memory, nor did he include the oral traditions of Greek history within the larger framework of oriental history.

Although there is no proof that Herodotus derived the ambitious scope of his own work - with its overarching themes of civilizations in conflict, divine retribution, and the instability of human fortune - from any predecessors, Homer was clearly another direct source of inspiration. Just as Homer relied extensively on a tradition of oral poetry sung by wandering minstrels, so Herodotus drew on an ancient Ionian tradition of story-telling, collecting and interpreting the many tales he heard on his travels. These oral histories often contained folk-tale motifs and demonstrated a moral, yet they also contained substantial facts relating to geography, anthropology, and history, all compiled by Herodotus in his uniquely idiosyncratic and entertaining style. The results are amazing in their extraordinary range and human variety. Less historically accurate than Xenophon's account of the Punic Wars and, clearly fantastical as they often are, the marvelous stories that Herodotus recounts nonetheless provide an invaluable insight into Ancient Greek beliefs about the people, cultures, and environment surrounding them.

The theme of retribution and vengeance - that those who commit evil deeds will pay for them now or in the future - is deeply woven into Herodotus' view of human action and historical causation. Like Homer, he begins his work describing a series of female abductions, first by men from Asia, then in retaliation by Europeans. Demands for satisfaction from the injured parties remain unmet and keep the cycles of vengeance alive. This desire for retributive justice ('tisis') not only motivates individuals, but also entire nation states. Thus Herodotus describes the Persian attack on Athens in 490 BC as retribution for the Athenians' participation in the burning of Sardis eight years earlier. The Athenians in turn portray their actions as pay back to the Persians for their previous incineration of the Acropolis and its temples. This notion is so deeply ingrained that it even carries over into the natural world. When flying snakes mate, Herodotus claims, the female latches on to the male's neck and kills him, but the female "has to pay for her behaviour, for the young in her belly avenge their father by gnawing at her insides, until they end by eating their way out" (Book III).

Herodotus also shared the common Greek belief that any act of insolence or pride ('hybris') inevitably leads to some kind of destruction ('nemesis'). Herodotus makes the Athenian jurist Solon, who had written of such things in one of his poems, the spokesman for this point of view, telling the enormously wealthy, but disastrously myopic Lydian king Croesus that "God is envious of human prosperity and likes to trouble us" (Book I). Another dramatic example is provided at the conclusion Book IV, when the Cyrenian Queen Pheretima gains revenge for the murder of her son Arcesilaus, first by impaling the men of Barca on stakes around the city wall, then by cutting off their wives' breast and sticking them up too: "Pheretima's web of life was also not woven happily in the end. No sooner had she returned to Egypt after her revenge upon the people of Barca, than she died a horrible death, her body seething with worms while she was still alive. Thus this daughter of Battus, by the nature and severity of her punishment of the Bracaeans, showed how true it is that all excess in revenge draws down upon men the anger of the gods."

Herodotus underlines the inherent dangers of the tall poppy syndrome in the warning given by Artabanus to Xerxes - "It is always the great buildings and the tall trees which are struck by lightning. It is God's way to bring the lofty low, for God tolerates pride in none but himself" (Book VII). Perhaps most clearly of all, Herodotus sees in the destruction of Troy "that great offences meet with great punishment at the hands of God" (Book II).

'Hybris' was often manifested in the expansion of empire. Campaigns against distant peoples frequently involved some transgression of natural limits, as when Cyrus crosses the River Araxes to conquer the Massagetae at the ends of the earth (Book I); when Darius bridges the Danube to bring over the Scythians to his empire (Book IV); and when Xerxes yokes the Hellespont, joining Europe and Asia in his attempt to conquer the Greeks (Book VII). All three expeditions are inevitably doomed to failure. After the Greek naval victory at Salamis, Themistocles comments that the gods and heroes "were jealous that one man in his godless pride should be king of Asia and of Europe too" (Book VIII).

Closely related to this kind of karmic retribution is the perceived instability of human fortune. In delineating the scope of his work, Herodotus says that he will tell of small cities and great, for the cities "which were great once are small today; and those which used to be small were great in my own time" (Book I). This belief is once again given substance by Solon's advice to Croesus, warning him that the sum total of a human life from beginning to end is necessary in order to calculate happiness, since "often enough God gives a man a glimpse of happiness, and then utterly ruins him" (Book I). Motivated by the same knowledge, the Egyptian king Amasis renounces his alliance with the tyrant Polycrates when he realizes that the latter's unbroken streak of good fortune will inevitably come to a miserable end (Book III).

It would be incorrect, however, to suggest that Herodotus had no sense of free will or human choice. The vast majority of actions that occur in The Histories are decided without divine intervention and with wholly human motives. In a direct Homeric legacy, the greatest part of his work employs imitation ('mimesis') and his characters are presented to us as they act. Another legacy is the use of direct speech, by which characters defend their actions, reveal their intentions, and motivate others. Unlike the speeches in Homer, which can be quite lengthy, those in Herodotus are usually short, terse, and dramatic. Such speeches mark one of the major differences between ancient and modern historiography, and were a natural consequence of Herodotus' desire to achieve in prose what Homer had already demonstrated in poetry.

Thus the role of Fate and the eternally revolving Wheel of Fortune is shown to affect both gods and mortals alike. Those who rise to the top, whether by fair means or foul, are inevitably cast down. The only thing that can be predicted with any degree of certainty is that the constantly rotating Wheel of Fortune plays an unremitting role in the sublunary world. Inexorably, according to Herodotus, we will reap what we sow - and in the end it all turns to dust anyway. Piles of rubble still surround many of the remaining buildings and monuments in Athens and Rome, bearing witness to the vanity of man's greatest achievements.

Alexander's Lineage

- the Missing Link

When

Alexander's sarcophagus was brought from its shrine,

Augustus gazed at the body, then laid a crown of gold on its

glass case and scattered some flowers to pay his respects.

When they asked if he would like to see Ptolemy too, 'I

wished to see a king,' he replied, 'I did not wish to see

corpses.'

- Suetonius, Life of

Augustus.

Alexander the Great provides the missing link between the lineages of Ancient Greece and Rome. After the Spartans under Lysander finally defeated Athens in the Second Peloponnesian War during the final decades of the fifth century BC, it was the Macedonian Alexander who became the supreme Greek celebrity, the military commander whose fame as a master of tactical warfare spread from the Mediterranean to the mountains of Afghanistan (where he was known as Iskandar), even as far Samarkand, Amritsar, and the Punjab. When he decided to go in search of the Eastern Ocean (the edge of the world as the Greeks conceived it) and discovered India instead, his guide was Herodotus. The annual flooding of the rivers, Indian clothing woven from wool-bearing trees, and the native flora and fauna (including hemp) were all described in Herodotus' terms. As for his gold-digging ants - "I did not see them myself," wrote Nearchus, a childhood friend of Alexander's and admiral of his Indian fleet, "but many of their pelts were brought into the Macedonian camp." If his dragoman was Herodotus, it was Homer's heroic themes that connected the stories of Alexander's youth to Julius Caesar and his successors, who attempted to emulate his imperial achievements.

"'Take this son of mine away and teach him the poems of Homer'," King Philip supposedly said to Aristotle in the wildly fictitious narrative known as the Romance of Alexander (which first took shape in Egypt, some five centuries after Alexander's death): "And sure enough, that son of of his went away and studied all day, so that he read through the whole of Homer's Iliad in a single sitting." Through his mother Olympias, Alexander considered himself a direct descendant of Achilles; his first tutor Lysimachus owed part of his life-long favour to giving his pupil the nickname of Achilles; and his beloved Hephaestion was compared by contemporaries to Patroclus, the intimate companion of Homer's hero. Aristotle taught him Homer's poems and helped to prepare a special text of the Iliad which Alexander valued above all his other possessions. According to one of his officers, he used to sleep with a dagger and this private Iliad under his pillow, calling it his journey-book of excellence in war. If Homer was his favourite poet, "Ever to be best and stand far above all others" was thought to be his best-loved line. Even in his dreams, Alexander lived out the poems he most preferred: only one is recorded and it could hardly be more appropriate - as he laid out his vision for a new Alexandria in Egypt, a venerable old man with the look of Homer himself is said to have appeared in his sleep and recited lines from the Odyssey that advised him where to locate his city.

Another anecdote relates that when a messenger arrived with such good news he could barely conceal his delight, Alexander stopped him with a smile. "What can you possibly tell me that deserves such excitement," he asked, "except perhaps that Homer has come back to life?" Alexander began his Asian adventures with a pilgrimage to what was then the village of Troy in order to honour Achilles' grave and took sacred armour from Troy's temple with him to India and back again. His own court historian, Callisthenes, a flatterer who wrote largely to please him, picked up on this theme and stressed parallels with Homer's poems in his reports. The effects were more subtle in the plastic arts, for if Alexander's appearance was deliberately modeled on young Greek heroes, his features also came to influence portraits of Achilles until the two could hardly be distinguished out of their context. The court sculptor Lysippus portrayed Alexander holding a Homeric spear and on coins of various small Thessalian towns that claimed to be his birthplace the picture of the young Achilles grew to resemble Alexander. The comparison was important, for when the Athenians appealed to him for the release of prisoners they sent as their ambassador the only man by the name of Achilles known in fourth-century Athens. Previous embassies had failed, but this time the Athenian prisoners were released.

As the classical historian Robin Lane Fox observes in recounting this episode, it is the "smallest details which are often the most revealing." When Alexander arrived at Troy, he anointed himself with oil and ran naked to the tombstone of Achilles in order to honour it with a garland, while Hephaestion did likewise for the tomb of Patroclus. It was a remarkable tribute and marks Hephaestion's first mention in Alexander's career. The two were already intimate and the comparison with Achilles and Patroclus would remain to the end of their days, since by Alexander's time it was entirely acceptable for them to have enjoyed the homosexual relationship about which Homer had only to felt free to offer hints.

Whatever his true feelings for

Hephaestion, Alexander was quite prepared to swing both ways

when there was a political advantage to be gained. He

married three times, may have fathered a child with an

Indian princess, and was even rumoured to have slept for

twelve days with a visiting Queen of the Amazons near the

Caspian Sea. Barsine, his Persian mistress whom he captured

at Issus, later bore him a son, but this did not prevent him

from marrying the beautiful Bactrian princess Roxane. The

wedding celebration was portrayed by the contemporary Greek

painter Acteon, whose painting (though now lost) won a prize

at the festival games of Greek Olympia, and survived through

a Roman visitor's description to influence later versions by

both Sodoma and Botticelli. Just as Achilles took the

captured Briseis as his concubine (and possibly his bride),

Alexander also married a prisoner as proof of his goodwill

to the conquered Iranian aristocracy. Nobody could have

predicted, however, that a pupil of Aristotle who had once

refused to take a wife, would also fall passionately in love

with this princess from outer Iran. Quite how Hephaestion

felt about all these liaisons has not been recorded, but he

assisted as best man at their wedding, depicted by Acteon

holding a blazing torch and leaning against a young boy,

probably Hymenaios, the god of weddings.

As we shall see in Part II, the enduring appeal of sex and violence provides a contiguous thread throughout the history of Ancient Greece and Rome, raising issues which percolate all the way down to the Renaissance and questions that remain relevant to many contemporary controversies and conflicts. These complexly structured relationships between past and present provide the enduring terms of reference for any discussion about influence and tradition in the history of Western culture. A repetitive pattern of creation and destruction, birth and death, and even rebirth and reincarnation remains its most salient and fascinating characteristic.

ANZCA: Health Reforms Raise Fears Of Two-Tier System And Workforce Shortages

ANZCA: Health Reforms Raise Fears Of Two-Tier System And Workforce Shortages Māpura Studios: A Matariki Exhibition At Historic Alberton House

Māpura Studios: A Matariki Exhibition At Historic Alberton House Doc Edge Festival: Finalists For The Doc Edge Awards 2025, an Oscar®-qualifying event

Doc Edge Festival: Finalists For The Doc Edge Awards 2025, an Oscar®-qualifying event Yachting New Zealand: 'A Win For The Squad' - Young 49er Team Strikes Gold At European Champs

Yachting New Zealand: 'A Win For The Squad' - Young 49er Team Strikes Gold At European Champs Michael King Writers Centre: Shilo Kino Awarded 2025 Shanghai Writing Residency

Michael King Writers Centre: Shilo Kino Awarded 2025 Shanghai Writing Residency Burnett Foundation Aotearoa: S.L.U.T.S Might Be The Answer To Ending Syphilis Outbreak

Burnett Foundation Aotearoa: S.L.U.T.S Might Be The Answer To Ending Syphilis Outbreak