Wellington Film Society Screens Terry Gilliam's Subversive Brazil

Harry Tuttle: Bloody paperwork, huh?

Sam Lowry: I suppose one has to expect a certain amount.

Harry Tuttle: Why? I came into this game for the action, the excitement. Go anywhere, travel light, get in, get out, wherever there's trouble, a man alone. Now they got the whole country sectioned off, you can't make a move without a form.

Full kudos to the Embassy Theatre for stepping up to the plate and hosting the Wellington Film Society, after the owners of the Paramount committed an unpardonable act of cultural vandalism when it shuttered the country's oldest movie theatre last year. While the Paramount remains an empty shell of its former glory, the Film Society is appropriately enough opening their 2018 season with Terry Gilliam's delightfully subversive Brazil.

With a brilliant screenplay co-written by Tom Stoppard and Charles McKeown and a magnificent cast (including Jonathan Pryce, Katherine Helmond, Ian Holm, Bob Hoskins, Ian Richardson, Peter Vaughan, Jim Broadbent, Robert De Niro, and Michael Palin), Brazil is indisputably one of American cinema's finest achievements. It was ranked thirteenth in Entertainment Weekly's Top 50 Cult Films of All-Time, included among the AFI's 1998 list of the four hundred movies nominated for the Top 100 Greatest American Movies, and listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die by Steven Schneider. Technically innovative, superbly imaginative, and extremely funny, it is hard to believe Brazil was made over thirty years ago. If further recommendation were necessary, it is worth recalling that it was also Frank Zappa's favourite film.

While Gilliam regards it as the first installment of a dystopian 'Satire Trilogy' (together with Twelve Monkeys and The Zero Theorem), Brazi has also been considered as the second in his 'Trilogy of the Imagination' (the first being Time Bandits and the third The Adventures of Baron Munchausen). All three movies depict individuals trying to escape from a repressive and overly-regimented social structure, as seen through the eyes of a child, a middle-aged man, and a senior citizen respectively. Jonathan Pryce's character Sam Lowry was originally conceived to be in his mid-twenties and written specifically with him in mind. After many years during which the screenplay languished in development limbo, Gilliam altered his age to late thirties so that the 37-year-old Pryce could still play the role, which he has described as one of the two highlights of his career (the other being Lytton Strachey in Christopher's Hampton's Carrington).

The film's title derived from an experience Gilliam had on a beach in the UK one Summer. Despite the typically inclement weather, he saw a man sitting alone on the sand listening to Ary Barroso's beautiful 1939 ballad Aquarela do Brasil. Gilliam was so struck by this image of a solitary individual overcoming adversity through the transcendent power of music that he decided almost all of the soundtrack would be a variation on the melody, which not only became the film's musical theme, but also provided its title. Gilliam has also stated that the movie's conclusion was actually the first idea that came to him, after wondering what kind of story could have its hero go insane as a happy ending. After Lowry's harrowing experience of an alienated, cold, and lonely existence in a mechanised future, refusing to submit to an inhumane system by entering a catatonic state in which he could no longer be hurt by torture (or even death) is actually a redemptive form of victory.

Although the first sound in the film is the limpid Telecaster guitar of Amos Garrett, both Geoff Muldaur and Kate Bush recorded versions of the song for the soundtrack, and the theme is incorporated throughout Michael Kamen's orchestral score. The musical motif is also heard several times within the film's diegesis: when Lowry punches "ERE AM I JH" into the secret elevator's control panel, it plays the first eight notes of the melody; he hums the tune when he sends the refund check up the pneumatic tube at Kurtzmann's office; it is played on his car radio; and Tuttle whistles it in his flat. There are a few exceptions - when Kurtzmann discovers the cowboy movie playing on the computer monitors in the Records Department, the accompanying music is Flying Messenger by Oliver Armstrong (also used during Lancelot's attack on the Swamp Castle in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which Terry Gilliam co-directed).

The film's attenuated plot serves largely as a pretext to lure the audience into obscure corners of an Orwellian dystopia that is both extremely dark and bleakly hilarious. Lowry is a Winston Smith/Everyman character, a grey-suited, fedora-wearing bureaucrat who nurtures a forbidden love, revels in a lively fantasy life, and endures a socialite mother whose bizarre fashion sense favours hats that resemble inverted shoes. Ida is constantly accompanied by her in-house plastic surgeon, Jack Lint, played by a marvelously malignant Michael Palin (Brazil has the greatest number of rhinoplasts per capita than any other country in the world). She seems to spend most of her time lunching with a variety of equally bizarre lady-friends, and the rest worrying about her son's limited career prospects. Ida pulls a few strings to arrange his promotion, only for him to wind up in an office so small that he shares half a desk (and half a poster) with the minatory bureaucrat in the adjacent cubicle. While this propels Lowry into a romance with a woman who may or may not be a terrorist, and then through a series of increasingly traumatic nightmares, much of Brazil's astonishing ingenuity derives from a plethora of sight gags and visual details that convey a terrifying sense of how everything (mal)functions in this sinister and chilling new society.

Brazil’s demented Stygian domain is controlled by constantly chugging machinery that no one has quite figured out how to upgrade. Despite (or perhaps because of) the overarching automation of standardized procedures, basic mistakes and brutal errors are depicted with farcical frequency throughout the film. It was Stoppard who introduced the brilliantly Kafkaesque idea of a dead insect falling into a computer and causing the typographical error that leads to a man's death and the fatalistic sequence of narrative events that inevitably follow. The malevolent and bespectacled technician who swats the fly that falls into the printer and causes the lethal misprint is played by Ray Cooper, Elton John's percussionist and a producing partner in George Harrison's Handmade Films. He sets in motion a number of uncontrollable processes that take pace within a constant maelstrom of movement, the mechanisms of bureaucracy accelerating too rapidly for anyone to keep pace, like the group of power-walkers who struggle to keep with Lowry during his orientation at Information Retrieval. Everyone goes about their business at warp-speed, too anxious and afraid to review and correct the disastrous blunders left in their wake.

While it is tempting to view Lowry as the lone voice of sanity in a world ruled by bureaucracy run amok, part of Brazil’s genius is the way it reveals how everyone who inhabits this universe exists on the verge of constant neurasthenic collapse. Lowry’s mumbling, robotic coworkers constantly flip their screens to Casablanca to avoid the mind-numbing boredom of their work. Ian Holm's anxiety-riddled supervisor Kurtzmann is a jittery ball of nerves, a sycophantic middle-manager completely incapable of asserting his own authority. Spoor and Dowser, the aggressive repairmen who come to fix Lowry’s air conditioning unit, bubble with panic at the mere mention of the phrase “27B/C” (the form they need to finish their work assignment, but have misplaced). All those at the lower end of the food chain are screaming for release from their regulatory prisons.

McKeown contributed most of the ironic propaganda slogans that are seen throughout the film, including the Christmas shopping scene in which a woman is carrying a banner with a cross that says "Consumers for Christ." Other signs glimpsed in the background include ''Loose Talk is Noose Talk'' and ''Suspicion Breeds Confidence,'' while television ads promote fashionable heating ducts ''in designer colours to suit your demanding taste'." Norman Garwood's fastidious production design ensures these omnipresent heating ducts are visible in almost every shot. Surface politeness and accurate record-keeping are paramount - when the hapless Buttle is arrested in his own living room, stuffed into a large canvas bag, and led away, never to be seen again, his wife is given a written receipt for her confiscated husband. Fascists are always good at completing the correct paperwork.

In addition to the

dazzling screenplay and soundtrack, much of the film's

appeal lies in the extraordinary acting talent assembled by

Gilliam. According to Helmond, he told her "I have a part

for you, and I want you to come over and do it, but you're

not going to look very nice in it." During production, she

spent ten hours a day with a mask glued to her face and

several of her scenes had to be postponed due to the

blisters this caused. Gilliam somehow managed to lure Bob

Hoskins away from the set of Francis Ford Coppola's The

Cotton Club for his cameo as Spoor, as well as recruit

De Niro who was also under contract for another movie at the

time.

Over half a dozen actresses were auditioned to play the part of Jill Leyton, including Rosanna Arquette, Ellen Barkin, Jamie Lee Curtis, Rebecca De Mornay, Rae Dawn Chong, Kelly McGillis, Kathleen Turner, and even Madonna. Gilliam's personal favourite was Barkin, because he thought her combination of sex appeal and toughness would work best. While Kim Greist gave an excellent audition and his close circle of friends and family advisors liked her, Gilliam picked her mainly because she had only one previous film credit (C.H.U.D.), and he thought this would let her create an original character unburdened by prior expectations. However, he later conceded that working with Greist had proved extremely difficult and taught him the invaluable lesson that "experience really does count for something." He was so unhappy with Greist's performance that many of her scenes were either drastically trimmed or cut completely. For much of the movie, she is seen wearing a bandage on one of her hands, which Gilliam said was added to give her character "more personality."

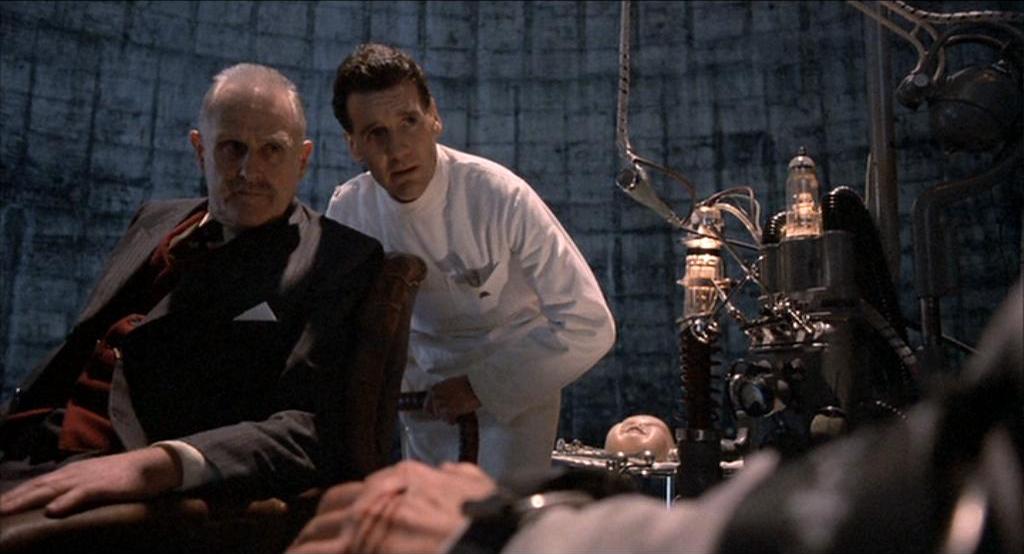

De Niro was pulled into the project as much by his friendship with producer Arnon Milchan, as his love for Monty Python. Initially, he wanted to play the role of Lint, but Gilliam had already promised this to Palin, so he was cast as Tuttle instead. At first Gilliam was delighted De Niro was on board, but began to find his obsession with detail increasingly irritating, later saying he "wanted to strangle him." In preparation for his role, De Niro likened its technical precision to that of a neurologist, insisted on witnessing brain surgeons perform in their operating theaters, and supplied Tuttle's tool belt and all of its gadgets. While most of the cast needed only a few takes to deliver their lines, De Niro insisted on twenty-five to thirty and still managed to forget his. His scenes were eventually completed in two weeks (rather than the five days originally planned), for which he was paid $660,000, three times what Pryce received. Despite a twenty-week shooting schedule, it took nine months to finish filming and the movie eventually came in at around $15 million. Maxim magazine reported Gilliam was so stressed out during production that he lost all feeling in his legs for a week.

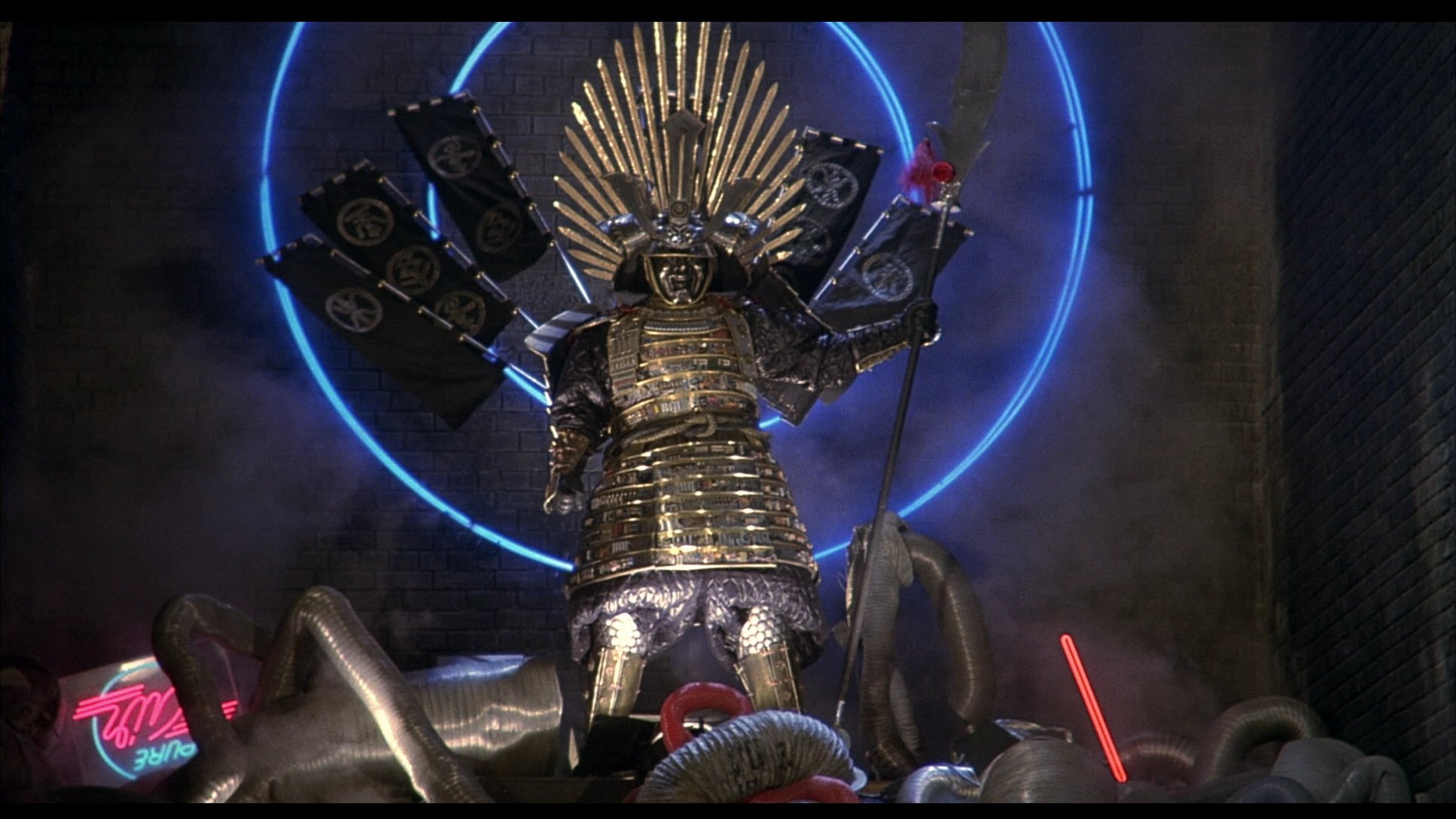

The end result was well worth such temporary discomfort, since Gilliam still managed to cram his frame with an awesome array of cultural, literary, and cinematic allusions. In an overt homage to the famous Odessa Steps sequence in Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin, the uniformed security police are seen walking down a staircase and firing their guns while a vacuum cleaner, rather than a baby carriage, rolls down the steps. The samurai warrior is not only a huge, monolithic, and overpowering machine that represents the faceless violence of technology, but also reflects Gilliam's fascination with Japanese culture in general and his admiration for the films of Akira Kurosawa in particular. The warrior's suit is covered in dozens of electronic components, such as resistors and volume knobs. When Lowry strips off its mask only to discover his own face, it implies that he too is a willing participant in the creation of this anonymous governmental monstrosity. In his director's commentary, Gilliam acknowledged that representing Lowry's dual nature in this manner was based on a pun suggested by Stoppard - 'Sam, you are I.'

Brazil's

groundbreaking visual style is achieved by grimly oppressive

Brutalist architecture decorated with delicate touches of

visual humour. While Gilliam’s stifling Expressionism

portrays a world obsessed with the convenience of

technology to the point where individual agency is totally

relinquished, the costumes hark back to a steampunk vision

of 1930s - as does the film's title, with the vapid gaiety

of the music clashing in ironic contrast to the suffocating

totalitarian society in which the story is situated. The

poster that reads 'Information is the Key to

Prosperity/Ministry of Information,' is a reference to

Vladimir Mayakovsky's famous Soviet 1923 advertisement

poster, Rezinotrest, and employs the same layout,

typeface, and colours (half of the word "prosperity" is

printed in green and half in red) as the original. The tiny

bubble-topped car that Lowry drives is a three-wheeled,

two-cycle, one cylinder Messerschmitt Kabinenroller

(or 'covered scooter'), built in Germany in the late 1950s.

Gilliam has also stated that the restaurant bombing scene

was inspired by the IRA terrorist attacks that occurred

across the UK during the 1970s - TV Interviewer: How do you

account for the fact that the bombing campaign has been

going on for thirteen years? Helpmann: Beginner's luck.

Although Franz Kafka's nightmarish visions of social control and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World are alluded to indirectly, the abiding literary influence is clearly 1984. Although Gilliam admitted that he never actually read the book, he conceded that his film was largely inspired by Orwell's prophetic novel and even assigned it the provisional working title of "1984 And A Half" (a combined reference to Federico Fellini's 8½). The idea was scrapped after Michael Radford's film version of 1984 was released and due to potential legal issues with the Orwell estate. When Lowry first visits Lint, the elevator ascends to floor 84. The reference to form 27B/6 is another reference to Orwell, who lived in Apartment 27B, Floor 6, Canonbury Square, while writing parts of 1984. The dates on Buttle's paperwork show he was received by the MOI on June 31, 1984 - exactly half way through the year. Other working titles for the film included The Ministry, The Ministry of Torture, How I Learned to Live with the System - So Far, and So That's Why the Bourgeoisie Sucks.

The names of various characters are also significant. Kurtzmann ('short man') is named after Harvey Kurtzman, the diminutive editor of Help magazine, for which Gilliam worked in the mid-sixties (he met John Cleese at a photo shoot for the magazine). When Helpmann spells out the elevator code that Lowry's father uses to get to his floor, the letters can be rearranged to read JEREMIAH, Lowry's father's name, literally 'helping' Lowry to identify him. Warrenn's workplace is a mazelike complex of endless corridors, a bewildering and labyrinthine rabbit-warren. Archibald Buttle's wife is named Veronica - an obscure reference to Archie and Veronica of Archie Comics, which is why she never blinks during her extended monologue when Lowry visits her apartment. Harvey Lime takes his name from Harry Lime, the shadowy and manipulative arms dealer played by Orson Welles who pulls the strings behind the scenes in Carol Reed's The Third Man.

Gilliam closely studied and absorbed many of the Kenosha Kid's pioneering techniques. Citizen Kane, Touch of Evil, and his version of Kafka's The Trial demonstrate Welles' enduring predilection for rapid cross-cutting, overlapping dialogue, matte images, miniature models, low angles, wide lenses, and long traveling shots. Julian Doyle's extraordinary editing, Roger Pratt's lush cinematography, and Norman Garwood's visionary production design all illustrate highly creative variations on these specifically cinematic effects pioneered by Welles. During the opening scene, in which we see the paperwork floor with all of the runners dropping and picking up receipts, there is actually only one row of typing stations. The actors and actresses just pass forward and backward along the same set of stations. Although a huge new Paris apartment complex called Marne la Vallee provided the setting for Lowry's Tower Block, when Tuttle leaps up on a balcony and disappears down a wire cable fourteen stories up, the little figure zipping down a cable was an inch-high lead figure dropping along a wire through a two-foot-high model building.

In the final scene, the rails embedded in the walkway out to the middle of the torture chamber were actually functional, and used to dolly the camera back and forth. They are clearly visible when the camera rapidly pulls back from a close-up of Lowry's head to a wide shot of the entire chamber. During the escape sequence towards the end, the SWAT team walks into the room where a stenographer is still typing up what Lowry has revealed under torture, suggesting that he is still being scarified and experiencing some kind of self-induced hallucination in order to transcend the physical pain. It becomes increasingly apparent that the whole sequence is imaginary, gradually allowing the viewer to grasp its unreality before the bleak truth is eventually revealed.

These constant and disconcerting shifts between appearance and reality are best exemplified by the dream scenes, which were initially intended to form one long sequence in the middle of the film. Technical problems made this impossible, however, and an editorial decision was made in post-production to separate the dream scenes in order to fill the 'empty' spaces between chapters more effectively. One of the most striking dream sequence is the scene in which Lowry flies over a vast field of eyeballs that slowly start moving to follow his descent. The eyes were made of snooker balls with false irises painted on. Glimpsed briefly among Lint's instruments of torture are a baby's pacifier and a bouncy rubber ball, and many characters are depicted wearing strange glasses, magnifying spectacles, or protective lenses. Such self-reflexive marking of vision occurs throughout Brazil and is a repeated visual motif in many other Gilliam films, including Time Bandits and Twelve Monkeys.

Jack Matthews'

The Battle for Brazil: Terry Gilliam v. Universal

Pictures provides a fascinating account of the many

problems Gilliam encountered with Universal Studios

executives. Studio head Sidney Sheinberg initially refused

to release the film because he deemed it overly pessimistic

and not commercial enough for mainstream audiences. He

demanded a "happy Hollywood" movie that eliminated (among

other things) the final transition, and a critical line of

dialogue that reveals Jill's tragic fate. Gilliam threatened

to disown the film entirely and conducted a guerilla PR

campaign that eventually resulted in the film remaining

essentially the way he intended it to be seen (although the

US release still omitted the line about Jill and Sheinberg's

butchered version, called Love Conquers All, was

aired on US television).

The story goes that Gilliam was invited to teach a film class at USC and took advantage of the situation by preparing to bring an "audio visual aid," which turned out to be his original cut of the film. Two days before the event, students advertised a free screening and Universal immediately tried to prevent it happening. During his speech to the class, Gilliam was constantly interrupted by phone calls from irate studio executives, who eventually agreed to let him show a few clips. Gilliam nevertheless went ahead and screened the entire film, then repeated the screenings over the following fortnight. It was at one of these viewings that Los Angeles film critics first saw the film and awarded it their Best Picture of the Year award. While the studio was still blocking the film's release and trying to re-edit its infamous Love Conquers All version, video copies of the Director's Cut also began to circulate around Hollywood. Several influential critics started asking whether a film that had been completed, but not released, could be eligible for a Best Picture Oscar.

During this long and widely publicized dispute, Gilliam bought a full-page ad in Daily Variety, which cost around $1,500 at the time and was bordered in black like a funeral invitation. It read: "Dear Sid Sheinberg, when are you going to release my film? Signed: Terry Gilliam." Gilliam and De Niro then appeared on Good Morning America to promote the film. De Niro rarely made television appearances, and according to Gilliam "said very little - but he was talkative that day, so we might have gotten him to ten words." Host Joan Lunden asked Gilliam, "I hear you're having trouble with the studio, is this correct?" "No, I'm having trouble with Sid Sheinberg," Gilliam replied, holding up his 8x10 photograph. Sheinberg was reportedly furious, but finally gave in to Gilliam's demands, rather than face further humiliation for trying to censor such a lauded film. Gilliam took a final swipe at Sheinberg by listing his name in the end credits as 'Worst Boy.' The entire saga is especially ironic, given that the film's main theme concerns a lone individual fighting for freedom of expression against the totalitarian autocracy of the surveillance state.

Brazil is an entirely fitting opening film for The Wellington Film Society's new season at the Embassy Theatre. Not only is it culturally clairvoyant and politically prescient, but also a uniquely cinematic experience that should be seen on a big screen to be fully appreciated. Its underlying ambiguities make its attitude toward administrative bureaucracy and social engineering hard to pinpoint with precision: some critics think it reveals the endless grinding down of individuality under the heel of an ineffectual, yet overly interventionist government; others consider it more applicable to the economic and social austerity of Thatcherism than Trump's mercenary, deregulated, and heavily weaponized America. However we may chose to decode its specific political message, Brazil remains a clarion call to strive for a better world in which everyone is free to live, love, dream, and dissent as they see fit. Those of us who are alarmed about the constant encroachment on our privacy by political and commercial interests would do well to heed O'Brien's ominous promise to Winston Smith at the end of 1984 - "We shall squeeze you empty and then we shall fill you with ourselves." Then take reassurance from the immortal words of Harry Tuttle - “We’re all in this together.”

DIRECTORIAL TRADEMARKS

1. Cameo appearance - the smoker in the Shangri-La Tower who bumps into Lowry is played by Gilliam.

2. Many characters are imprisoned in cages or wear masks in Gilliam's films. He intended the combination of doll-like baby masks and the decaying bodies of the Forces of Darkness (the small, troll-like creatures which Lowry sees in his dreams) to represent an "intermingling of the beginning and ends of life." Lint's creepy mask was based on one his mother gave him as a child and which had haunted him ever since.

3. SWAT teams frequently burst into buildings violently and unexpectedly, either entering through ceilings or smashing through walls (cf. "Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition").

4. The gift that Lowry keeps getting and receiving is an executive decision maker, with a plunger that can fall to one side of a divider, landing on either 'YES' or 'NO.' It underlines the essentially random nature and arbitrary element of chance in all artistic choices (cf. the music of John Cage, William Burroughs' cut-up techniques, and Brian Eno's Oblique Strategies).

Hospice NZ: Hospices At Risk Of Disappearing

Hospice NZ: Hospices At Risk Of Disappearing Health Coalition Aotearoa: New Bill A Vital Step Towards Tobacco-Free Future In Aotearoa

Health Coalition Aotearoa: New Bill A Vital Step Towards Tobacco-Free Future In Aotearoa National Youth Theatre: 140 Christchurch Kids Shine In National Youth Theatre’s Historic CATS Premiere

National Youth Theatre: 140 Christchurch Kids Shine In National Youth Theatre’s Historic CATS Premiere NZ Symphony Orchestra: NZSO To Tour Masterworks By Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn And More

NZ Symphony Orchestra: NZSO To Tour Masterworks By Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn And More Journal Of Public Health: Vape Shops Cluster Around Schools

Journal Of Public Health: Vape Shops Cluster Around Schools Timaru District Council: Aigantighe Art Gallery Hosts An Iconic Robin White Touring Exhibition

Timaru District Council: Aigantighe Art Gallery Hosts An Iconic Robin White Touring Exhibition