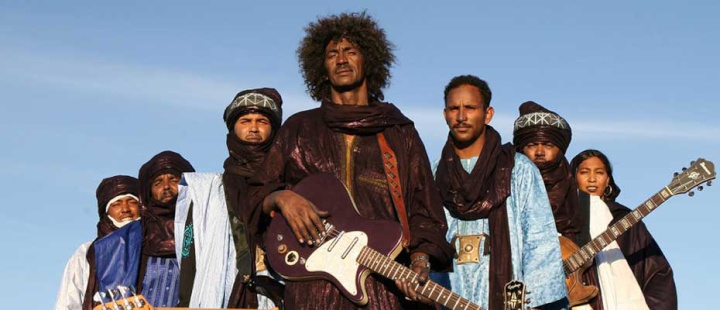

Malian band Tinariwen (playing WOMAD NZ in March 2018) are a band comprised of true musical revolutionaries in every sense. Active since 1982, these nomadic Tuareg or ‘Kel Tamashek’ (Tamashek-speaking) electric guitar legends revolutionised a traditional style to give birth to a new genre often called ‘desert blues’. They also have a history rooted deeply in revolution and fighting for the rights of their nomadic Tamashek speaking culture and people. The rebellious political nature of this music is far from pantomime; many of the original members of the band fought in the “great rebellion” against the Malian army in 1990-91 and used music to spread the message of rebellion among their dispersed tribes. They are still profoundly passionate about the right of their language and culture to exist and flourish, but for now they are seeking to ensure this happens through their music.

Don’t for a minute let all this fool you into thinking they can’t party - these guys and their music are truly funky, shredding their electric guitars in climactic solos like Hendrix with tabs beneath their turbans all locked into a pounding trance-like syncopated sub-Saharan African rhythm.

I first heard Tinariwen in the early 2000’s when they burst onto the world scene and was blown away by the passion and vibe conveyed by the music. Despite the inability to understanding the lyrics (except those you can pick up with your sixth form French), the soulfull nasal back-of-the- throat vocals of lead singer Ibrahim Ag Alhabib pierce some long forgotten evolutionary part of your being. You can just feel the sizzling energy of the desert coming off the hypnotic interlocking slide guitar and scorching lead solos like a hot Saharan wind. The interlocking African hand percussion, chants, claps and bass rhythms are absolutely trance-inducing with elements reminiscent of the music of the griots – a highly esoteric ancient Saharan spiritual tradition of bards.

I remember being fascinated to hear their revolutionary back-story and the personal struggles they have endured to get where they are. I am so excited about hearing them play live as they have continued maturing and developing musically and their latest album is excellent. Here’s a taster while you read their story below:

The Story of Tinariwen

The socio-political realities of the modern world have been tough on the nomadic Tamashek-speaking people who are spread across Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Libya, and Algeria. Over the past century, their history has been one of constant struggle for survival in an unforgiving territory desired by outsiders. They have suffered under (and rebelled against) the rule of the French colonial army, and later against the post-colonial governments that emerged. Band leader Ibrahim Ag Alhabib lost his father to the first Tuareg rebellion of 1963, sending him on the path of rebellion. In the eighties, when Qaddafi offered military training to the Tamasheks, thousands answered his call. He and the other founding members of Tinariwen were among them, meeting in a Libyan training camp, and playing their first performances there. Legend has it they once performed a song for Qaddafi himself. According to some reports, at times during the war, Tinariwen’s cassettes were the only recorded music that could be found in some remote areas.

Out of these conditions of severe adversity and struggle, Tinariwen emerged as a musical expression of the Kel Tamashek rebellion, giving voice to the longing of a people for freedom to pursue their traditional way of life. In 1992, the government of Mali signed a peace treaty with the rebels, and Tinariwen’s fighting days came to an end. Tinariwen then began singing about Kel Tamashek unity to overcome the internal tribalism and factionalism being exploited by the Malian Government. However, they have not forgotten their roots. “We are military artists!” Abdallah Ag Alhousseini, one of the group’s guitarists and singers, once told a journalist from Algérie News. “Today, if we see that our brothers need fighters rather than musicians, we will go to the front, because we are always ready to answer the call of the preservation of our land, our values, and our culture. This is what we do through music, and we will do it again with arms!”

There is no doubt that Tinariwen's success launched a renaissance and explosion in Tamashek guitar music, the ripples of which are still felt today. This music, often labelled ‘desert blues’ or ‘Tuareg Guitar’ or just ‘guitar’ in Mali - is the cultural inheritance of their race. Their own name for it is ‘Assouf’, which doesn't directly translate. In the liner notes of Tinariwen's Aman Iman album, an unnamed nomad is paraphrased saying that assouf is everything that lies in the darkness beyond the light of the campfire.

Tinariwen is thought to be the first Tamashek electric guitar band, making them akin to Bob Dylan. Like Dylan, by plugging in, they have forever changed this traditional folk music style, but in doing so have ensured its continued relevance and ability to flourish in the modern digital world. Before them, the style was passed down only through the generations of nomadic tribes and shared across their region (along with a fair smattering of revolutionary political propaganda) by the exchange of low-resolution recordings on cassette tapes. Without this rennaisance, there was the very real possibility this musical tradition would wither away and be forgotten.

As Joe Tangari writing for Pitchfork puts it: “Tinariwen have rightfully grown to international fame-- they are for the Kel Tamashek essentially what Bob Marley was for Jamaica, an emissary that confronts the struggle and sadness of their people head-on in infectious, emotionally charged songs. This is Tinariwen's other great innovation: When they moved on from playing traditional songs rooted in the past to playing their own compositions that spoke of modern turmoil and dreams, they became the sound of their people.”

Tangari is spot on there – Tinariwen combine a unique mél/nge of an obscure and dying cultural and musical tradition and the present-day and future ambitions of an oppressed people. Ultimately their music is both nostalgic and traditional while also hopeful and modern, giving the people of this nomadic culture a sense of belonging, continuity and hope for a better future. It is no surprise with this combination that they have attracted a huge international following. This was no easy feat; it took them two decades of hard graft circulating cassettes, interrupted by war in northern Mali, Algeria and Niger in the late 80s and early 90s. Now there is a proliferation of second-generation bands such as Bombino who are also gaining critical acclaim, but they all look for inspiration to Tinariwen – in fact some people call them “the children of Tinariwen”.

Roots of Kel Tamashek Music

The label ‘desert Blues’ is actually a bit misleading in its implications of unoriginality. Conversely, it actually points to the fact that musicologists have traced the origins of the modern blues to the Malian region. As Joe Tangari again describes the blues connection of Tinariwen’s work:

“The pentatonic scales echo those heard along the curve of the Niger River, and it's easy to draw a line through the music of Senegal, Guinea, southern Mali, and other parts of West Africa straight to American blues.”

In other words these guys are no imitators – they are descendants of the original bluesmen - playing in a style they have inherited down the generations. Their music is still very much their own - it draws on traditional Kel Tamashek chant music played on distant relatives of the guitar. The guitar as an instrument is actually descended from the melding of Arabic and North African music and first emerged in its modern form in the Moorish empire leading to the emergence of flamenco guitar of Andalusia in Southern Spain. It is perhaps unsurprising then that the instrument was adopted with relish by the Tamashek from the 1960s onwards when it began to appear in the region.

The historic roots of Kel Tamashek musical mix lie in their interesting history as a nomadic culture of caravan traders wedged between a number of colliding worlds. To the South are the sub-Saharan African cultures, to the east is the Arabic world and to the north is Spain and the Colonial French. Like many nomadic cultures Kel tamashek have picked up elements of these other cultures they have come into contact with along the way. For this reason, Flamenco, Arab and the Berber orchestras of North Africa and Lebanese string music are all in the mix in Tamashek music, making for a diverse and deep musical tradition.

The Sub-Saharan Soul of Tinariwen

However, the soul of the Kel Tamashek music, one could argue, comes from the griots of the Sahel region, a semi-arid band of land that spans Africa to the south of the Sahara. A griot is a repository of oral tradition, a bard or troubadour. Similar to a 'tohunga'- the griot is often seen as a societal leader due to his or her traditional position as an advisor to royal personages. According to Paul Oliver in his book on the griot, Savannah Syncopators "he has to know many traditional songs without error, he must also have the ability to extemporize on current events, chance incidents and the passing scene. His wit can be devastating and his knowledge of local history formidable".

These griot elements are also present in the tradition of the famous Southern Malian musician Ali Farka Toure who no doubt influenced the fledgling Malian musicians of Tinariwen. Toure is the world’s best known Malian blues musicians and on hearing him it is hard to question that Mali and the griot tradition are indeed the origin of the blues and ultimately of the social and political commentary and free-styling of hip-hop.

Although they are popularly known as "praise singers", griots may use their vocal expertise for gossip, satire, or political comment. It is this political commentary aspect of the griot tradition that Tinariwen and the Tamashek people have incorporated into their music most enthusiastically. In true griot fashion, Tinariwen have used their music it as a vehicle for spreading the message of the emancipatory goals of their historically maligned and oppressed people. In a sense Tinariwen have been the bards or griots of their generation, spreading groovy songs of highly charged emotion and inspiration to their people.

What does the Future Hold?

Andy Morgan writes in the Guardian:

“The Sahara is in a mess. It’s not just the terrorism, kidnapping, drug trafficking and other headline-hogging afflictions (the ones that tend to obsess western governments and analysts), it’s the vicious subsoil from which those headlines grow: the poverty, corruption, political indifference, underdevelopment, armed conflict and desertification. Those underlying calamities turn the daily lives of many Saharan people into a grinding struggle. The modern world has not been kind to them or to their old nomadic ways.”

Given the continuing difficulties they face in a world that, even in the most progressive regions, consistently fails to acknowledge the human rights of nomadic peoples, the Kel Tamashek sorely need heroes such as Tinariwen and their offspring. However their cause was not helped in 2013 when in the Islamist rulers of Mali banned music across two-thirds of the country. Three years later in 2016 the Guardian reports that there are signs things are improving. “Low-level violence continues in the north and beyond, with an Islamist attack on a hotel in the capital in November and a similar terrorist assault in Burkina Fasoin January. But there are signs that things are changing….. These days bands perform in bars in the capital most nights of the week and regular street parties have whole neighbourhoods dancing.”

The hypnotic and soulful sound of Tinariwen has become the soundtrack of cultural resistance and rebellion in the region and it is impossible to hear it and not be moved. Let's hope that the ongoing war in this region does not claim another generation of gifted youngsters who could continue this musical legacy and ensure the survival of a language, a musical tradition and ultimately a Culture.

See Tinariwen live at WOMAD

2018 16 -18 March 2018, in New

Plymouth

Jacob Douglas Motorsport: Douglas Heads To The Oval After Breakthrough Victory

Jacob Douglas Motorsport: Douglas Heads To The Oval After Breakthrough Victory Research For Maori Health and Development: Bridging The Gap In HIV Prevention For Māori - Insights And Resources Now Available

Research For Maori Health and Development: Bridging The Gap In HIV Prevention For Māori - Insights And Resources Now Available Tertiary Education Union: Weltec And Whitireia Cuts A Shocking Blow For Their Communities

Tertiary Education Union: Weltec And Whitireia Cuts A Shocking Blow For Their Communities PHARMAC: Pharmac Proposes To Fully Fund Nutrition Replacements For Some People With Crohn’s Disease

PHARMAC: Pharmac Proposes To Fully Fund Nutrition Replacements For Some People With Crohn’s Disease Nōku Te Ao: Bringing Together Voices On Mental Distress, Stigma And Discrimination Under One Roof

Nōku Te Ao: Bringing Together Voices On Mental Distress, Stigma And Discrimination Under One Roof Office of Early Childhood Education: Early Childhood Education Sector Confidence Survey Results 2025

Office of Early Childhood Education: Early Childhood Education Sector Confidence Survey Results 2025