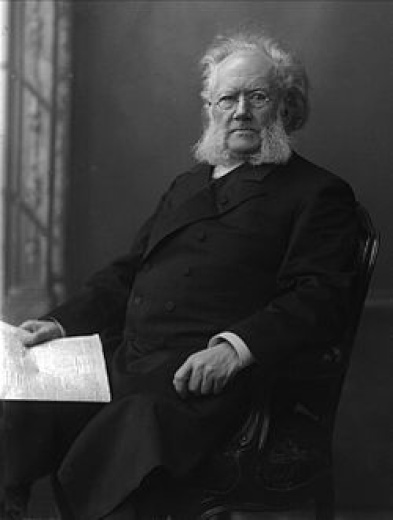

Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) is

considered to be one of the founders of theatrical Modernism

and is often referred to as "the father of realism" in the

European tradition. Richard Hornby described him as "a

profound poetic dramatist - the best since Shakespeare." He

had a profound influence on many writers, including George

Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Henry James, Edith Wharton, James

Joyce, Eugene O'Neill, and Arthur Miller, and was nominated

for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1902, 1903, and 1904.

Ibsen applied a probing poetic intelligence to the

conditions of contemporary life and conventional morality

and his later dramas were considered quite scandalous at a

time when the theatre was expected to model strict morals of

family life and social propriety. Instead, he examined the

falsity of social façades with a critical eye, revealing

the highly unsettling domestic underbelly of emotional

repression and neuroses that lurked beneath its surface

probity.

A Doll's House premiered at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen in 1879 and by the early 20th century had become the most performed play in the world. Set in an anonymous Norwegian town, it depicts the fate of a married woman who lacks both the opportunity and resources for self-fulfillment in a male-dominated society. It was greeted by a maelstrom of bewilderment, controversy, and outrage that extended beyond the theatre to the world of newspapers and society in general. Ibsen based his drama on the life of Laura Kieler and much of the interplay between the characters of Nora and Torvald happened to Laura and her husband, Victor. Laura needed money to treat her husband's tuberculosis and signed an illegal loan to try and save him. She wrote to Ibsen, asking him to recommend her work to his publisher, hoping that increased sales of her book would repay her debt. After he refused, she forged a check for the money, but when Victor found out about the secret loan, he divorced her and committed her to a mental asylum. Two years later, she returned to her husband and children at his urging and went on to become a well-known author, living to the age of 83.

Ibsen wrote A Doll's House soon after Kieler had been committed. Her fate shook him deeply, especially because she had asked him to intervene and he had been unable or unwilling to do so. Instead, he turned this tragic situation into a drama in which Nora leaves Torvald with head held high - though facing an uncertain future, given the disapproval that divorced women faced at the time. Although he did not begin its first draft until a year later, Ibsen started thinking about the play in May 1878, having reflected on the themes and characters in the intervening period as constituting a "modern tragedy:" "A woman cannot be herself in modern society," he argued, since it is "an exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint."

A Doll's House fundamentally questioned traditional gender roles and conventions in 19th-century bourgeois marriage. For many Europeans this was considered a scandalous interrogation. While George Bernard Shaw found Ibsen's willingness to examine society without prejudice exhilarating, August Strindberg questioned Nora leaving her children behind with a man of whom she disapproved so strongly that she felt she could no longer remain with him. Strindberg also thought that Nora’s involvement with an illegal financial fraud (forging a signature and lying to her husband regarding Krogstad’s blackmail) was a serious crime that raised important questions about the play's conclusion, when Nora moralistically judges her husband. He pointed out that Nora’s complaint she and Torvald “have never exchanged one serious word about serious things” is contradicted by much of the dialogue in the play's first two Acts. By Act Three, however, the illusion of married bliss completely unravels (culminating in a spectacular scene in which Nora's lie is exposed and Torvald first blames, then forgives her), and is finally abandoned as Nora recognises the truth of her situation. She accuses her husband and her father before him, of having used her like a doll, declaring herself unfit to be a wife or mother until she has learned to be herself. Ibsen's final stage direction, of the door closing violently behind her, is one of the most famous ever written.

The reasons why Nora decides to leave Torvald are complex and Ibsen hints at various motives throughout the play. In the last scene she tells him she has been “greatly wronged” by his disparaging and condescending treatment and his attitude towards her in their marriage. Their children in turn have become her “dolls” and she has begun to doubt whether she is even qualified to raise them. Confused by Torvald’s behaviour and deeply troubled by the scandal of the loaned money, she finds she no longer loves her husband and feels they are strangers, suggesting these emotions are shared by many married women. Shaw imagined that she left to begin “a journey in search of self-respect and apprenticeship to life” and that her revolt is “the end of a chapter of human history.” Because of her radical rejection of traditional behaviour (and theatrical convention), Nora's final act of slamming the door on her past to face an uncertain future has come to represent the play itself. One contemporary critic noted, "That slammed door reverberated across the roof of the world."

In the century and a half since it was written, both the play and the role of Nora have assumed iconic status, with UNESCO's Memory of the World register calling her "a symbol throughout the world, for women fighting for liberation and equality." Her character has become a symbol for all female actors, both of what is possible and of how much they still have to fight for, when most plays and films still feature more male than female characters and work tends to dry up for older women - unless they are among a lucky handful of national treasures. Unsurprisingly, the feminist movement embraced the play and various modern film and television versions were made, notably a live TV broadcast in 1959 directed by George Schaefer, starring Julie Harris, Christopher Plummer, Hume Cronym, and Jason Robards; a 1974 West German TV adaptation, titled Nora Helmer, directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder; and two movies released in 1973, one directed by Joseph Losey starring Jane Fonda, David Warner, and Trevor Howard, the other by Patrick Garland with Claire Bloom, Anthony Hopkins, and Ralph Richardson.

Ibsen's radical departure from convention and tradition has also been seen as having broader implications, with biographer Michael Meyer arguing that the play's theme is not exclusive to women, but rather "the need of every individual to find out the kind of person he or she really is and to strive to become that person." In 1989, Ingmar Bergman staged a shortened reworking of the play entitled Nora that was widely viewed as downplaying the feminist themes of Ibsen's original and heightening the play's melodramatic aspects. In a speech given to the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights in 1898, Ibsen himself insisted that he "must disclaim the honour of having consciously worked for the women's rights movement," since he wrote "without any conscious thought of making propaganda," his task having been "the description of humanity." The central dilemma that Ibsen presents - how to be simultaneously yourself and true to yourself, while being married and being a parent - is certainly not a problem exclusive to women. Perhaps the play's most radical aspect is that it articulates a specific woman's dilemma as a larger human issue, relevant to both sexes, when so often women's stories are treated as a special subject of concern only to women. The play is about the unravelling of a family and one approach is to sweep away some of the feminist baggage it carries and treat it as the story not of a woman, but of anyone who feels trapped in a tortured and unfulfilling relationship.

However difficult it may be to accept how suddenly Torvald's "sweet little skylark" turns into Emily Pankhurst, it is also hard to ignore the play's strong feminist resonances in a culture where any woman who puts herself in the public eye may become a target for abuse. Which may be why some of the current generation of women directing and adapting A Doll's House have sought to reassert its feminist credentials. Director Carrie Cracknell made a short film that imagined Nora as an overstretched modern mother, her life a nightmare of spilled porridge, missed appointments, and hurriedly applied makeup. She says working on the play made her acutely aware of ideas about gender that shaped her parenting of her two young children: "We live in a culture in which the way we represent women is becoming narrower. I think we have a generation of women growing up who understand that power is linked to how we look."

Emily Perkins confronts these issues

head-on in her radically inventive re-imagining of the play

at Wellington's Circa Theatre, transplanting and updating it

to current-day New Zealand with varying results. As Kenneth

Tynan wrote of Michael Meyer's earlier translations, her

dialogue is certainly "crisp and cobweb-free, purged of

verbal Victoriana." But by throwing in contemporary

references to everything from Smartphones and iPads to

social inequality, child abuse, finger puppets,

eco-villages, and "living off the grid," she has difficulty

in clearly delineating Nora's reasons for abandoning her

family - especially as it involves leaving behind such a

pair of adorable children. Portraying Nora's behaviour as a

reaction against the trendy anti-materialist pieties of the

PC brigade, rather than Ibsen's larger targets of tradition,

male misogyny, and social conformism, allows Perkins to take

aim at more than a few sacred cows. It is no accident that

the contents of the 'swear-box' is ultimately inverted over

Torvald/Theo's head, the third item to fall from the rafters

after the dreaded Xmas packaging and sugar candies. Perkins'

extensive overhaul introduces a plethora of extraneous

factors that broadens Ibsen's original focus on female

repression to address problems of control and

(mis)communication that are present in every relationship.

By re-modelling Ibsen's blueprint so substantially, however,

she risks complicating and confusing the logic of Nora's

actions, making Strindberg's critique of the play's

architecture appear all the more legitimate.

A further imbalance occurs in terms of the casting, with the effortlessly expressive Kali Kopae (who so ravishingly inhabited the role of Frieda Kahlo in La Casa Azul) dominating every scene in which she appears. Seldom can such an alluring actor have made a secondary character the focus of attention by appearing initially brazen, bitchy, and self-assured, then transforming into someone just as weak, vulnerable, and wounded as the rest of us. Arthur Meek makes a mild-mannered, considerate, and handsome husband - until he suddenly slings the C-word at Nora, which simply underscores why she should never have trusted a man in pink underwear who doesn't wear socks in the first place. Sophie Hambleton (Katydid, Westside) commands the lead with consummate assurance, modulating Nora's transition nicely, but struggles to make her final dramatic exit entirely convincing. Two short, diverting, but ultimately unnecessary musical interludes, involving a Christmas carol and a lap dance, are awkwardly spatchcocked into the already-busy stage business and could easily be cut.

Despite such dramaturgic difficulties, this is exactly the kind of thoughtful, challenging, and adventurous production we have come to expect from Circa, revealing precisely why Ibsen's play remains eminently relevant to audiences everywhere. Hopefully, having Prime Minister Bill English present at opening night may at least have caused him to consider the complicated and complex politics of urban planning, climate change, and alternative lifestyles in a somewhat different light.

Bowls New Zealand: Lawson And Grantham Qualify To Keep Bowls Three-Peat Hopes Alive

Bowls New Zealand: Lawson And Grantham Qualify To Keep Bowls Three-Peat Hopes Alive Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At South Bay And Peketā Beaches And Kahutara River Upstream Of SH1

Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At South Bay And Peketā Beaches And Kahutara River Upstream Of SH1 Wikimedia Aotearoa NZ: Wikipedian At Large Sets Sights On Banks Peninsula

Wikimedia Aotearoa NZ: Wikipedian At Large Sets Sights On Banks Peninsula Water Safety New Zealand: Don’t Drink And Dive

Water Safety New Zealand: Don’t Drink And Dive NZ Olympic Committee: Lydia Ko Awarded Lonsdale Cup For 2024

NZ Olympic Committee: Lydia Ko Awarded Lonsdale Cup For 2024 BNZ Breakers: BNZ Breakers Beaten By Tasmania Jackjumpers On Christmas Night

BNZ Breakers: BNZ Breakers Beaten By Tasmania Jackjumpers On Christmas Night