COLIN McCAHON'S

'ON GOING OUT WITH THE TIDE'

By Howard Davis

"I sing my paintings to myself"

- Colin McCahon, 1972.

Now that the egregious excrescence of Cindy Sherman's cos-play has finally gone the way of all flesh, Wellington's City Gallery has mounted a extensive retrospective of Colin McCahon's work from the 1960s and 1970s. Curated by Wystan Curnow and Robert Leonard, On Going Out with the Tide features major works that have been assembled from public and private collections across New Zealand and Australia. It focusses on McCahon’s evolving engagement with Māori subjects and themes, ranging from early treatments of koru imagery to later history paintings which refer to Māori prophets and investigate land-rights issues. Presenting these works in terms of a tectonic shift in New Zealand culture and an emerging sense of biculturalism, the exhibition emphasizes the historical context of McCahon's output during these years not only in terms of when it was produced, but also the ways in which it has been subsequently interpreted. To facilitate this wider perspective, City Gallery is also presenting an accompanying programme of lectures, talks, and screenings.

The first major exhibition of McCahon's work in fifteen years, it fills the ground floor of the Gallery, with the first room full of works from 1969 based on Matire Kereama’s book The Tail of the Fish, including The Canoe Tainui - the most expensive work to sell at auction in New Zealand. Other rooms address specific places - Muriwai (where McCahon had his studio), Parihaka, and Te Urewera. Robert Leonard comments, “The exhibition is an opportunity to consider how increasing awareness of Māori culture and concerns shaped the work of New Zealand’s most celebrated artist’s most important period. We know there will be divergent views. The show does not presume to offer the last word on the work- its meaning, significance, and politics - but to provide a platform for discussion."

McCahon's name is now synonymous with New Zealand art, which has largely developed around his work, with critics debating its various virtues and implications, and other artists producing work in response to it. He emerged in the late 1940s and stayed active into the early 1980s, during which time his approach underwent radical formal and conceptual transformations. His diverse oeuvre includes landscapes, figurative paintings, abstractions, as well as text and number paintings. It has proved to be both inventive and inspiring, crucial and consequential, and has continued to cast a long and influential shadow.

In the 1950s, McCahon and his family lived in a small house in the Titirangi bush, where he painted some of his most important works, and now operates as a museum and artist residency. With his friend and kindred spirit James K. Baxter, McCahon shared a non-conformist relationship with Catholicism, an enduring love of words and poetry, and a sense of reverence towards nature. Like Baxter, McCahon was nourished by Māori culture, friendships with other writers and artists, and the births of his Māori grandsons, Matiu and Peter (Tui). While McCahon’s interest in Māori culture sustained and consolidated longstanding features of his earlier work, it also fundamentally altered it.

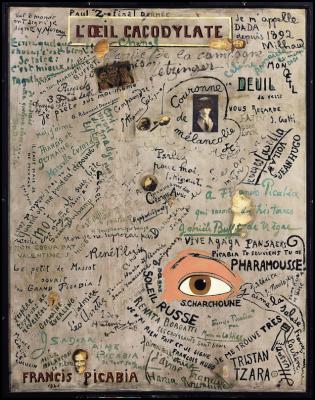

One of the most striking aspects of the exhibition is the number of works that play with words and texts. In itself, this is nothing new - think of the kind of exquisitely refined calligraphy found in Chinese and Japanese scrolls that combine the most delicate poetry with similarly polished and sophisticated brushwork. McCahon's influences are literally much closer to hand. When Francis Picabia exhibited his L'Oeil Cacodylate (The Cacodylic Eye) at the Salon d'Automne in 1921 it was regarded as a display of Dadaist impudence - a shocking collage derived from experiments by Kurt Schwitters, Max Ernst, and Hannah Höch, who often used pages and stubs of paper bound for the trashbin, or old engravings ripped out of books. While Picabia himself always remained a painter, some of the gambles he took he took with oil on canvas undoubtedly came from a shared desire to undermine the art of painting and the conventional art world that encapsulated it in the language of Dada, which set out to dislodge the notion of the unique masterpiece made by the uniquely skilled master. Clearly, there is a similar impulse at work in McCahon's later work.

It may have been the fun of doing the lettering in his Portrait de Cezanne the previous year that led Picabia to L'Oeil Cacodylate, a picture that is partly about handwriting. After contracting an eye infection, he was told to stay at home and use cacodylic eyedrops, so he simply put up a five foot high canvas and invited friends over to visit and sign it. The picture was complete, he wrote with Dadaist disdain, when there was no room left for any more signatures. He himself described the work as "very beautiful," adding "is it is perhaps that all of my friends are artists just a bit?"

On one level, L'Oeil Cacodylate is an informal testimony to the range of Picabia's many friendships and the artistic vibrancy of Paris in the twenties. Tristan Tzara, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Jean Cocteau are all there, as is Fatty Arbuckle (who added "GOOD LUCK" after his name), Isadora Duncan, Darius MIlhaud ("je m'apelle DADA depuis 1892"), and Georges Auric ("je n'ai rien a vous dire"), while Francis Poulenc helpfully noted "j'aime le salade." Etymologically, however, the word 'cacodylic' derives from the Greek for 'foul-smelling.' Although the idea of a stinky eye has a very Dadaist ring to it, Picabia was justified in describing the painting as "beautiful" since it possesses an undeniable delicacy and formal strength. The swaying eddies of letters and curving linear flourishes that the various signatories could not resist adding create an intricate latticework that foreshadows the remarkable paintings with words that Joan Miro would produce a few yeast later. Its colours are delicately nuanced, with the black and pale green signatures balanced against the smudgy grey background by the title at the top, and anchored by Picabia's own name at the bottom (along with a photo of himself), in dark red capital letters. The snapshots and clippings that are pasted on add sparing flecks of white and tan, and the big, foul-smelling eye is surrounded by a swathe of pink.

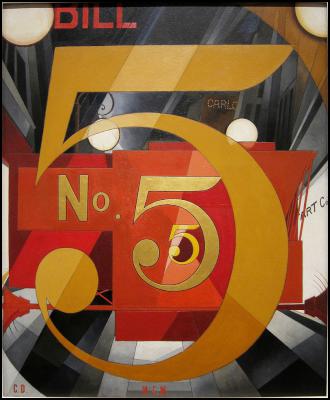

McCahon's playful use of lettering and puckish palimpsests possess a similarly childish, chalkboard quality, and are equally engaging. They not only share Picabia's sense of impudent exuberance, but are also Ralph Hotere's exploration of the qualities of 'blackness.' McCahon gradually infused his paintings with a degree of greater seriousness, however, as he began to consider serial ideas of sequential generation and genealogy, figures and figuration. This preoccupation with the implications of numerical and biological reproduction first became clear in a several of his paintings from the late1960s, and is directly connected to the birth of his grandchildren. Again, McCahon's interest in depicting numbers themselves is hardly without artistic precedent - consider the kind of cultural cross-pollination involved between William Carlos Williams' 1921 poem The Great Figure and Charles Demuth's 1928 I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, which Robert Indiana in turn adapted for a great many painterly riffs ...

But by the mid-1970s, McCahon's work had moved from the domestic and personal to the explicitly political. This transition is clearly evident in the current exhibition, where the deliberate infantilism and naivete of Tui Carr Celebrates Muriwai Beach (1972) is replaced by the The Song of the Shining Cuckoo (1974), which was inspired by the words of a waiata given to McCahon by Hotere, who had in turn learned it from his father. The shining cuckoo is a migratory bird, hence associated with Māori ideas about the flight of the soul after death. The work is painted on five drops of unstretched canvas, hung edge to edge, each drop subdivided into abstract landscapes. Horizontal lines suggest frame edges and horizons, while superimposed Roman numerals refer to the fourteen Stations of the Cross - the Catholic meditative practice by which we are reminders of key moments in the crucifixion. McCahon drew a dotted line across this arrangement, suggesting the flight of the 'bird/soul,' and gaps open up in some of the frames as though to permit easier passage through which the 'bird/soul' can negotiate temporal and spatial boundaries. The two ways to go through the painting (counting the numbers or joining the dots) represent alternative paths, just as the work itself suggests two distinct ways of contemplating death and the afterlife - Christian and Māori.

Such intimations of mortality may well have been prompted by the recent deaths of his mother and his friends James K Baxter, Charles Brasch, and RAK Mason. According to Maori legend, the spirits of the dead travel up the coast to Cape Reinga (the tip of the 'tail of the fish'), where they leap off the headland and descend to their traditional underworld homeland of Hawaiki. McCahon considered Muriwai as both a landing and a runway for souls heading north via Ninety Mile Beach to Cape Reinga, an idea that informs three 1973 works: the lengthy beachscape elegies to Baxter Walk (Series C) and Series D (Ahipara); and Jet Out from Muriwai, which includes both Māori and Christian cosmology to illustrate the idea of the spirit's flight after death with an airborne cross, simultaneously suggesting the resurrection and an airplane taking off.

The works in the final gallery deal specifically with the violent and unjust treatment of Māori during the colonization period. McCahon became interested in the Māori prophets not as a professional anthropologist or academic historian, but rather because they hybridized Christian and Māori beliefs and practices for political ends. McCahon realised there is a direct connection between the poetics of prophecy and the politics of painting.

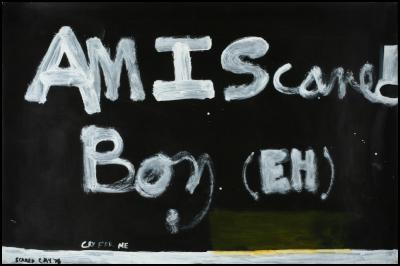

In December 1975, Peter McLeavey, who had included McCahon's A Poster for the Urewera No.2 in a group show, sent him a photograph of two young Māori hovering outside the doorway of his gallery, with the Poster hanging just out of their field of vision. In response, McCahon painted Am I Scared (1976), featuring the words "Am I Scared Boy (Eh)". On the lower edge, inscribed in tiny capitals, is the plaintive utterance "CRY FOR ME" - a phrase taken from a letter by Wiremu Hiroki to his whanau on the eve of his execution in 1882 for killing a pakeha surveyor.

Clearly, this is much more serious stuff than simply depicting Oaia Island as a kind of Captain Pugwash image of Moby Dick.

Colin McCahon's 'On Going Out

With The Tide' will be at City Gallery until July 30,

2017.

Prostate Cancer Foundation: Foundation Hails Select Committee Support For Prostate Screening Pilots

Prostate Cancer Foundation: Foundation Hails Select Committee Support For Prostate Screening Pilots Cross Street Music Festival: First Artists Announced For 2025 Cross Street Music Festival

Cross Street Music Festival: First Artists Announced For 2025 Cross Street Music Festival Bowls New Zealand: Lawson And Grantham Qualify To Keep Bowls Three-Peat Hopes Alive

Bowls New Zealand: Lawson And Grantham Qualify To Keep Bowls Three-Peat Hopes Alive Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At South Bay And Peketā Beaches And Kahutara River Upstream Of SH1

Te Whatu Ora Health NZ: Health Warning – Unsafe Recreational Water Quality At South Bay And Peketā Beaches And Kahutara River Upstream Of SH1 Wikimedia Aotearoa NZ: Wikipedian At Large Sets Sights On Banks Peninsula

Wikimedia Aotearoa NZ: Wikipedian At Large Sets Sights On Banks Peninsula Water Safety New Zealand: Don’t Drink And Dive

Water Safety New Zealand: Don’t Drink And Dive