Filling a gap in NZ’s history - Sewing Freedom Review

Filling a gap in New Zealand’s history

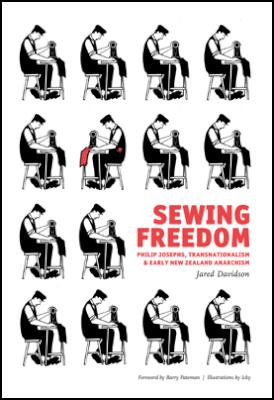

A review of Sewing Freedom: Philip Josephs, Transnationalism and Early New Zealand Anarchism by Jared Davidson. (AK Press 2013)

By Cameron Walker

Anarchism is an often misunderstood ideology. Proponents of anarchism believe in full equality between humans, the abolition of hierarchy and argue that workers’ collectives are a better form of human organisation than the state and the capitalist system. Sometimes the ideology is referred to as libertarian socialism or libertarian communism.

In the early Twentieth Century, newspaper reports and authority figures in many countries promoted an image of anarchists as terrorist bombers and nihilists. At the time socialist and union movements, with a large militant anarchist component, were challenging employers and governments in a number of countries across the World including the United States, Spain and Argentina. Anarchist writers and activists, such as Emma Goldman of the US and Peter Kropotkin from Russia became known around the World.

Jared Davidson’s book Sewing Freedom looks into the militant anarchist and socialist movement in New Zealand during the early decades of the Twentieth Century by focusing on the life of Philip Josephs, a Latvian born tailor, who fled to Scotland from anti-Semitic pogroms in his homeland and eventually moved to New Zealand in 1904.

Josephs became New Zealand’s most prominent exponent of anarchism, writing articles for the labour movement newspaper, The Maoriland Worker, distributing anarchist literature and hosting discussions on economic and social issues at his Wellington tailor shop. Josephs also founded a Wellington anarchist collective called the Freedom Group. Davidson never engages in a narrow biographical style. We not only learn about Josephs’ life but also gain a great picture of early 20th Century Wellington and the many social conflicts and struggles that erupted in New Zealand during this period, such as the 1912 strike in Waihi, in which a striker was killed and the 1913 great general strike.

Davidson clearly demonstrates that not only did ideas from overseas influence the early socialist and anarchist movement in New Zealand but also the experiences of the New Zealand left and working class movements influenced similar movements overseas. For example, thanks to the correspondence of Josephs and other New Zealand anarchists, anarchist publications in Europe and the US included coverage of the Waihi strikes of 1912 and the violence meted out to striking workers by the police and strike breakers. This led to questioning of American and European social reformers who saw New Zealand’s arbitration system of industrial relations as a model to be followed in other countries. For example, the US anarchist journal Mother Earth, published by Emma Goldman, began an article in February 1913:

‘The strike arbitration laws of New Zealand – so enthusiastically hailed by American reformers as an effective solution of labor troubles – is beginning to show results that fill its champions with anxiety and fear. ‘

The Scottish publication The Spur described New Zealand in the following terms “Of all British Dominions for scientifically suppressing revolutionary thought the New Zealand government is the worst”.

The intensity of state repression in New Zealand against opponents of militarism and conscription during World War I is rarely acknowledged today. Fortunately Sewing Freedom delves into this dark period. Wartime regulations allowed for the detention of people for reasons as simple as giving a speech against conscription. Davidson notes that wartime regulations were much stricter in New Zealand than even in Britain, which was much closer to the battlefield:

‘in New Zealand, seditious activity was a category of elastic dimensions, defined by the state in such a way as to encompass a broad range of activity – including anything deemed critical of the New Zealand government, the war effort and conscription’.

By the end of the war 287 people had been charged with sedition or disloyalty, 208 were convicted and 71 sent to prison. Josephs’ home and business was raided and his political books were confiscated. An appendix listing all the literature confiscated by the police is included at the end of the book.

Anti-militarists including contemporaries of Joseph were detained and maltreated on Sommes Island in Wellington Harbour: ‘prisoners were often made to exercise until they fainted, put in solitary confinement for meaningless infringements or taken down to the water’s edge and beaten…’. One comrade of Josephs, Carl Mummes, was detained on Sommes Island right until October 1919, almost an entire year following the declaration of Armistice.

One question the book does not deal with is if anarchism provides a viable form of organisation for fighting capitalism and its vicious exploitation, inequality and militarism in the long term. While many anarchists have taken part in progressive social movements, such as the union movement and anti-war campaigns, Sewing Freedom and Toby Boraman’s 2007 book Rabble Rousers and Merry Pranksters: a history of anarchism in Aotearoa/New Zealand from the mid-1950s to the early 1980s give the impression that explicitly anarchist organisations in New Zealand, such as Josephs’ Freedom Group have often been short lived and dissipated after certain key individuals moved overseas or ended their commitment to the anarchist movement for one reason or another. Such questions would be worth exploring in depth in any future book on anarchism in New Zealand.

Sewing Freedom provides a succinct but highly informative glimpse into an often overlooked period of New Zealand history. Those interested in the history of left wing movements, labour history or even New Zealand in general will gain something from reading it.

Copies of Sewing Freedom can be ordered from http://sewingfreedom.org/

ENDS

Health Coalition Aotearoa: New Bill A Vital Step Towards Tobacco-Free Future In Aotearoa

Health Coalition Aotearoa: New Bill A Vital Step Towards Tobacco-Free Future In Aotearoa National Youth Theatre: 140 Christchurch Kids Shine In National Youth Theatre’s Historic CATS Premiere

National Youth Theatre: 140 Christchurch Kids Shine In National Youth Theatre’s Historic CATS Premiere NZ Symphony Orchestra: NZSO To Tour Masterworks By Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn And More

NZ Symphony Orchestra: NZSO To Tour Masterworks By Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn And More Journal Of Public Health: Vape Shops Cluster Around Schools

Journal Of Public Health: Vape Shops Cluster Around Schools Timaru District Council: Aigantighe Art Gallery Hosts An Iconic Robin White Touring Exhibition

Timaru District Council: Aigantighe Art Gallery Hosts An Iconic Robin White Touring Exhibition Victoria University of Wellington: Dame Winnie Laban Awarded Honorary Doctorate Recognising Achievements For Pasifika

Victoria University of Wellington: Dame Winnie Laban Awarded Honorary Doctorate Recognising Achievements For Pasifika