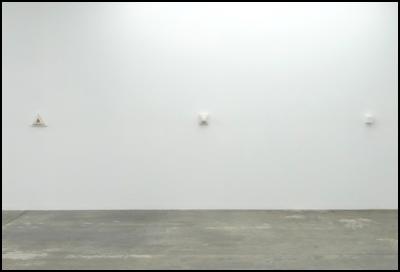

Julian Dashper, Untitled, new installation of works

Julian Dashper, Untitled, new installation of works

The current exhibition of work by Julian Dashper continues with a new installation of late works viewable from Friday 2 August until the exhibition closes on Saturday 17 August.

We are also pleased to extend the current exhibition Pale Ideas by Zac Langdon-Pole until Saturday 17 August.

Continued from ‘9 Views of

Julian Dashper’s Last Works’

by David

Herkt

4. Silence

Dashper’s

late white works are profoundly silent. While they might

surround themselves by noisy reference (McCahon, Malevich,

Rauschenberg, even as Dashper himself has indicated,

Warhol), they are, in themselves, as objects, silent

fissures. Where they are contained, it is a bare

containment. The titles are simply the holding vessel. Where

they are en-framed, the framing can be paradoxical -

‘Untitled’ is frequently the title. The title is the

handle of nothingness, the chat around the edge, through

which there is an illusion of grasp. They contain the quiet

of the tomb.

5. Poetry

There is

a whole aesthetic history of white space. “The page

intervenes” Stéphane Mallarmé’s writes concerning the

spaces that aerate his long poem ‘Dice Thrown Never Will

Annul Chance’ (1897). A note for his incomplete

(uncompletable?) ‘master work’ Le Livre, reads:

“The intellectual armature of the poem, conceals itself and - takes place - holds in the space that isolates the stanzas and among the blankness of the white paper; a significant silence that it is no less lovely to compose than verse.“

In painting, there is Malevich’s White on White (1918) and Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings (1951) were described by John Cage as 'White on white. The blank is coloured by a supplementary white'. But Dashper’s white paintings, also white on white, are somehow whiter. They might repeat a gesture, but it is not the same. Dashper’s white, reiterated through the late works, is intently composed. It contains all previous art-whites. It is conscious, contemporary, and contemplative. It is both readily available and completely unique. Let us propose a new name for this colour: Dashper White.

6.

Resurrection

McCahon’s ‘Victory over death

2’ (1970) with its categorical ‘I AM’, backed with all

the power of quoted biblical utterance and the black/white

claritas of its light/dark message, is the obvious and

acknowledged precursor to Daspher’s ‘Untitled (Victory

over death Part 3)’. Here, Dashper’s long dialogue with

McCahon comes to its conclusion in three white canvases

stepped one upon the other. The ascendant block shapes might

seem to owe more to the McCahon’s earlier ‘Practical

religion: the resurrection of Lazarus showing Mount

Martha’ (1969), multiplying the flat weight of McCahon’s

South Otago table-mountain to heaven, but it is the title of

McCahon’s later work that is preserved as the chief

signifier. Daspher’s practice, always economic, has

stripped everything away from the McCahon reference but the

reference itself. It is this which is coded as the next

step, the next thing, the Part 3. Function replaces form.

Dashper’s late works whittle away the inessential, until

there are bare gestures left. Bare, barer, barest.

7. Time

Dashper created any

number of works with a temporal component. ‘Untitled

(Portrait of Ben Curnow)’/‘The work consists of Ben

Curnow sitting at a desk in the gallery’ with its constant

change through its various past and future exhibitions and

terrible inevitable finality, when Ben Curnow will no longer

be able to sit and be seen. There is also, at the other

extreme, Curriculum Vitae (various dates), where Dashper’s

written biography and list of exhibitions are pinned to a

gallery wall. While the exhibitions are still added to the

exhibition-listing, right up to the exhibition of its

exhibit, the biography pages of Curriculum Vitae are

considered to have been completed. Dashper’s ‘Future

Call’ a work in which a telephone is phoned from New

Zealand (nominally always ahead of the rest of the world for

each new day) but is not answered. Dashper’s last

exhibited DVD works, Untitled (the last 15 seconds of the

last Venice Biennale) and Untitled (the last second of the

last Venice Biennale) are other examples, if more are

needed. But perhaps, instead of time as a subject in

Dashper, we should consider death. Death as absence. Or did

we always, despite the vitality, the humour, and the wit?

Were all Dashper’s works always poised upon the edge of

non-being, No’s Knife?

8. This Is Not The

End.

Dashper’s white works are deceptively

artless, but their apparent guilelessness is profoundly

Dashperian; their whites are not quite whites, their

painting is not quite painting, their more is just the same,

their artlessness, art. Their frames are without substance,

but only in a physical sense. When there is nothing, the

least gesture becomes thunderous. What do we do with works

like this, so apparently minimal, so initially recalcitrant

and apparently unforthcoming to interpretation? It is, as it

always was; they are become devices to manufacture meaning.

Dashper hands us a space in things, a kink in the forces, a

twist in time, and a history and a culture are played like a

Mobius strip for the production of art. ‘Death is imposed

on creative beings, not on works of art,’ Adorno wrote,

‘and thus it has appeared in art only in a refracted mode,

as allegory.’ Dashper’s late, great works are profound

and elegiac allegories.

9.

‘Untitled’

-July, 2013

ENDS

Wheels at Wanaka: Over 65,000 Wowed At International Vehicle Event - Record-Breaking Attendance At Wheels At Wanaka Over Easter Weekend

Wheels at Wanaka: Over 65,000 Wowed At International Vehicle Event - Record-Breaking Attendance At Wheels At Wanaka Over Easter Weekend Universities New Zealand - Te Pokai Tara: 2025 Critic And Conscience Of Society Award Winner Advocates For Health Policy Action

Universities New Zealand - Te Pokai Tara: 2025 Critic And Conscience Of Society Award Winner Advocates For Health Policy Action Rachelle Martin & Kaaren Mathias, The Conversation: 1 In 6 New Zealanders Is Disabled. Why Does So Much Health Research Still Exclude Them?

Rachelle Martin & Kaaren Mathias, The Conversation: 1 In 6 New Zealanders Is Disabled. Why Does So Much Health Research Still Exclude Them? Athletics New Zealand: Connor Bell Breaks NZ Discus Record (Again)

Athletics New Zealand: Connor Bell Breaks NZ Discus Record (Again) Tertiary Education Union: UCOL Cuts Will Cause Lasting Damage

Tertiary Education Union: UCOL Cuts Will Cause Lasting Damage National Library Of New Zealand: Kate De Goldi Named Te Awhi Rito Reading Ambassador For Aotearoa

National Library Of New Zealand: Kate De Goldi Named Te Awhi Rito Reading Ambassador For Aotearoa